![]()

PART ONE

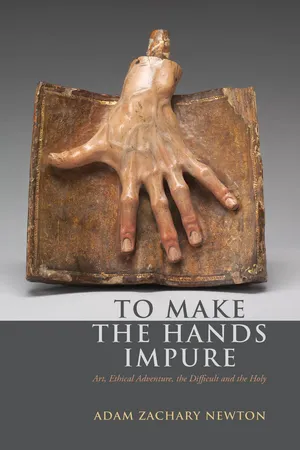

Hands

![]()

CHAPTER 1

Pledge, Turn, Prestige

Worldliness and Sanctity in Edward Said and Emmanuel Levinas

Apparently, he likes the tear (déchirure) but detests contamination.

—Jacques Derrida on Emmanuel Levinas

Indeed, nothing is more mobile, more impertinent, more restless than the hand.

—Emmanuel Levinas

Here is an ambition (which the Zahirites have to an intense degree) on the part of readers and writers to grasp texts as objects whose interpretation—by virtue of the exactness of their situation in the world—has already commenced and are objects already constrained by, and constraining, their interpretation.… (Incidentally, one of the strengths of Zahirite theory is that it dispels the illusion that a surface reading is anything but difficult.)

—Edward Said

TOUCHING ON MAGIC: LEVINAS

Every great magic trick consists of three parts or acts. The first part is called “The Pledge.” The magician shows you something ordinary: a deck of cards, a bird or a man. He shows you this object. Perhaps he asks you to inspect it to see if it is indeed real, unaltered, normal. But of course, it probably isn’t. The second act is called “The Turn.” The magician takes the ordinary something and makes it do something extraordinary. Now you’re looking for the secret, but you won’t find it, because of course you’re not really looking. You don’t want to know. You want to be fooled. But you wouldn’t clap yet. Because making something disappear isn’t enough; you have to bring it back. That’s why every magic trick has a third act, the hardest part, the part we call “The Prestige.”

So, in the familiarly glottalized timbre of actor Michael Caine’s voiceover, begins The Prestige, Christopher Nolan’s 2006 film about illusions and dueling illusionists. As John Cutter, ingénieur to both stage magicians and plots, speaks (to us?), we are shown a bird—real, unaltered, normal; the same bird placed in a cage; the same cage suddenly collapsed under an enveloping veil; the same veil then removed to reveal neither bird nor cage; and finally, the payoff or “Prestige”: to the delighted eyes of a young girl, the object is brought back—quite literally, a bird-in-the-hand. We recognize the trick as the classic parlor effect known as the “vanishing” (or “flying”) birdcage,” which is revisited several times in the course of the plot, as is Cutter’s patter.

But intercut with this brief riddling of the magician’s code, through the sleight of hand that is cinematic montage (for every film editor is a “cutter”), we glimpse another interrupted sequence that tells a major piece of the movie’s storyline. Like other Nolan films—Memento, Inception, and Insomnia, for example—intricate narrative structure accompanies a reflexive meta-plot or self-allegory: artwork as manipulation, as magic, as mirror, as maze, as misdirection, as mimesis. Like those films, The Prestige fully exploits what Walter Benjamin called the “optical unconscious,”1 a latent cinematic possibility in the “dream factory” ever since that industry’s … inception. George Méliès, the first “cinemagician”—two of whose early shorts, The Conjuror (1899) and The Vanishing Lady (1896) anticipate Nolan’s film—and Orson Welles—whom Nolan has cited as an influence—represent just two famous figures standing over The Prestige as antecedents in the tradition of filmic art as flimflam. To cite them here is merely to underscore the deep relation between movies and magic, a relation we revisit, along with Méliès, in Chapter 6.2

In Nolan’s film, Pledge, Turn, Prestige not only serves to elucidate the workings of stage-magic. It also slyly anticipates the three-part plot of the movie itself. Part patter, part prose-poem, part explanation, part plot summary, Cutter’s elucidation is the kind of double-talk associated with a not wholly reliable narrator whose vocation happens to be the inventing and engineering of tricks.3 If, analytically speaking, “magic is the dramatization of explanation more than it is the engineering of effects,” then Cutter’s three-act explanation opens onto the performative horizon of craft and artificing that magicians call “the real work”—“the complete activity, the accumulated practice, the total summing up of tradition and ideas—what makes a magic effect magical.”4

What goes unwitnessed by the little girl instructed by Cutter, however, is the fate of the original bird, which is crushed to death in the collapsed cage in order to facilitate the illusion. Mimesis as Prestige is costly: nothing is ever really brought back whole once it is pledged.5 This is the darker implication of Cutter’s instruction, and the essence of the interpolated plot sequence we see glimpses of—which is perhaps why we don’t want to know and prefer, rather, to be fooled. Manipulated and subject to sleight, the object-in-hand—like the film we happen to be watching—never really stays unaltered.

I begin this chapter with Nolan’s film because I want to speculate on two related matters: (1) art as its own complex apparatus of conjuring, and (2) the agency of those performing magicians we know as critics. If we thus employ a little stagecraft ourselves and throw its voice, Pledge, Turn, Prestige has yet another story to tell. In the ensuing pages, it will take shape through a counterpoint between certain reflections on text, reading, and the role of the critic. Specifically, we will track philosopher Emmanuel Levinas and literary theorist Edward Said as each practices his respective vocation of (quasi-)religious and (predominantly) secular criticism.

Let that story begin, however, with criticism’s repurposed version of the vanishing birdcage (minus the misdirection). What follows is an excerpt from an essay about the acts of reading and criticism, voice-over by Georges Poulet, a critic-philosopher on the oblique to Saidian and Levinasian postures alike.6

Books are objects. On a table, on bookshelves, in store windows, they wait for someone to come and deliver them from their materiality, from their immobility. When I see them on display, I look at them as I would at animals for sale, kept in little cages, and so obviously hoping for a buyer. For—there is no doubting it—animals do know that their fate depends on a human intervention, thanks to which they will be delivered from the shame of being treated as objects. Isn’t the same true of books? Made of paper and ink, they lie where they are put, until the moment some one shows an interest in them. They wait. Are they aware that an act of man might suddenly transform their existence? They appear to be lit up with that hope. Read me, they seem to say. I find it hard to resist their appeal. (53)7

If books seem to share something palpable with the animate world of captive pets (like, say, a bird in a flying birdcage), they share much less with their inanimate fellows—statues or vases, for instance.8

Buy a vase, take it home, put it on your table or your mantel, and, after a while, it will allow itself to be made a part of your household. But it will be no less a vase, for that. On the other hand, take a book, and you will find it offering, opening itself. It is this openness of the book which I find so moving. A book is not shut in by its contours, is not walled-up as in a fortress. It asks nothing better than to exist outside itself, or to let you exist in it. In short, the extraordinary fact in the case of a book is the falling away of the barriers between you and it. You are inside it; it is inside you; there is no longer either outside or inside (54).

Poulet’s 1969 essay “The Phenomenology of Reading” marks a fault line in the history of modern literary criticism and theory, and it was first given under the title “Criticism and the Experience of Interiority” for the famous Johns Hopkins conference “The Languages of Criticism and the Sciences of Man,” sharing space over that fault line with ground-breaking presentations by Jacques Derrida, Jacques Lacan, and Roland Barthes. It has been the subject of numerous critiques and commentaries since. My own contribution here consists merely in discerning what could be called a three-act drama—not quite Pledge, Turn, Prestige, but close enough.

Thus, Act I: once the book is opened, it ceases to be a material reality and is converted into the reader’s consciousness: “Unheard-of, I say. Unheard-of, first, is the disappearance of the ‘object.’ Where is the book I held in my hands? It is still there, and at the same time it is there no longer, it is nowhere” (54). Act II: “Je est un autre,” in Rimbaud’s famous ungrammaticality; the reading consciousness is altered.

This is the remarkable transformation wrought in me through the act of reading. Not only does it cause the physical objects around me to disappear, including the very book I am reading, but it replaces those external objects with a congeries of mental objects in close rapport with my own consciousness.… I am someone who happens to have as objects of his own thought, thoughts which are part of a book I am reading, and which are therefore the cogitations of another. They are the thoughts of another, and yet it is I who am their subject. The situation is even more astonishing than the one noted above. I am thinking the thoughts of another. (55)

Finally, Act III: the reader’s annexed or usurped consciousness and its full participation in the artwork cede to the disenchanted work we call criticism.

Thus I often have the impression, while reading, of simply witnessing an action which at the same time concerns and yet does not concern me. This provokes a certain feeling of surprise within me. I am a consciousness astonished by an existence which is not mine, but which I experience as though it were mine. This astonished consciousness is in fact the consciousness of the critic: the consciousness of a being who is allowed to apprehend as its own what is happening in the consciousness of another being. Aware of a certain gap, disclosing a feeling of identity, but of identity within difference, critical consciousness does not necessarily imply the total disappearance of the critic’s mind in the mind to be criticized. (60)

Et voilà: Pledge, Turn, Prestige transposed (with a little liberty) to the plane of textuality, along with the semi-magical agency exercised by critical consciousness in the act-event of reading.

How does Poulet, in turn, help us to think about further implications of John Cutter’s formula? Let us bring it back and see. Consider it now as an ars poetica for the workings of art, generally. For, all artistic enterprise—“the complete activity, accumulated practice, summing up of tradition”—is founded on something like the formula of a pledge, a turn, and a prestige, is it not? Architecture stakes a pledge on the transformation of space and surrounding element into social structure and habitation. Music stakes a pledge on mechanical waves of pressure realized in ordered configurations of frequency and pitch, duration and interval that enable song and rhythmic pulse. The plastic arts stake a pledge on the materiality of stone and wood, glass and textile, pigment and canvas rendered into design, pattern, image, and form. Dance stakes a pledge on the human body posed and mobilized through performance and social contact. Cinema (is there a more deceptive practice?) stakes a pledge on the illusion of movement generated by twenty-four frames per second, not to mention the bricolage of those cutter-magicians we know as editors; and like theater, film stakes a pledge on the stylized impersonation of person. Last but not least, literary and verbal representation stakes a pledge on language as both artifact and expression, and on the uncanny circuit of address between writers and readers.

And for each pledge in the history of these traditions, crafts, and practices, there is a corresponding turn: the artist takes something ordinary—a townhouse, say—and makes it extraordinary—like Antonio Gaudi’s Casa Batlló or Casa Milà. Likewise, for each—by some thing being brought back, smuggled in, or shown always to have been there even in disguise—there is the third act, the prestige. Diego Velázquez’s Las Meninas and Beethoven’s Diabelli Variations, Orson Welles’s Citizen Kane and Elizabeth Bishop’s “One Art,” Julio Cortázar’s Rayuela (Hopscotch) and short fiction by R...