![]()

CHAPTER ONE

A WORLD ASTIR: EUROPE AND RELIGION IN THE EARLY FIFTEENTH CENTURY

John Van Engen

In the early to mid-1430s, a young boy named Egbert walked through a public square in the market town of Deventer bearing a plate of food, eyes down, clothing and hair cut distinctively. Son of a nearby gentry family, he had been sent to the local Latin school, widely regarded as the best in the region (where Erasmus would go fifty years later), in hopes of securing him an advantageous clerical career. Once in Deventer he encountered a newish group of “Brothers” living a “Common Life.” They drew him toward another option, to choose spiritual rigor rather than careerist ambition. On this day he chanced to encounter a female relative in the square. When he did not lift his eyes to greet her, she knocked the plate out of his hand and exclaimed, “What for a lollard is this who goes walking about like that?”1 Here was a teenage relative of good family and fine education walking through town in a hyperreligious manner, as she saw it, lacking the courtesy even to greet kin, possibly harboring suspect views. The slur this woman reached for was “lollard.” It came from a Dutch word meaning “to mumble” and had originated as a dismissive gesture toward extraordinarily religious persons who spent their time, as it appeared, mumbling prayers, much as the word beguine sprang from a French word of more or less the same meaning. She might instead have used beghaert, a word suggesting someone “puffed up,” especially about religion. These words would accumulate multiple meanings over time: a slur directed at anyone accounted hyperreligious, the accepted slang for groups living specially religious lives outside formal religious orders, a tag for individuals with dubious spiritual views or practices, sometimes all three working at once—which would then, confusingly, also become true in historians’ subsequent use of these terms.2 The word lollard seemingly migrated across the Channel, doubtless from seaport to seaport, from the Low Countries to England (though some have also suggested a native English origin).

What should we make of calling someone a lollard in the mid-1430s at Deventer?3 Had the term moved back to continental Europe freighted with new meaning in the wake of Master John Wyclif? Had lollards become the talk of seaport towns? It’s hard to say. This slur might echo Wyclif’s condemnation at the Council of Constance, lollard thus taking on tones not only of the hyperreligious and suspicious but of the seriously heretical. No allusions to Wyclif or lollards as such appeared however in the flurry around the Sisters and Brothers of the Common Life, though they were themselves pursued early by an inquisitor and then a decade or so later by a hostile Dominican. On the continent Hussites loomed larger in popular rumor and worry. These were people sustaining open rebellion against church and emperor and threatening Prague, the capital of the empire and the home to central Europe’s earliest university, and sometimes outside Bohemia they were labeled Wycliffites. Hussite also occasionally appears as a general slur in early fifteenth-century Europe, though likewise nearly never applied to the Sisters and Brothers of the Common Life.

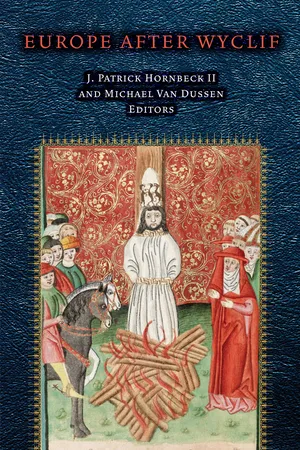

Traditional accounts of medieval heresy have framed lollards and Hussites as national heresies. This label mirrored the nineteenth century’s preoccupation with the nation-state as well as romantic notions of national character, even as it echoed and perpetuated inherited protestant genealogies for the Reformation. What we make of this story of young Egbert—or, on a grander scale how we position lollards and Hussites in late medieval society and culture—hinges upon how we frame religious stirring broadly in fifteenth-century European society. One temptation is to make religion and especially religious upheaval nearly the whole story, another to treat such dissenting groups largely apart from European society and religion more generally. Since the 1980s John Wyclif, together with those writings and teachings in English and Latin deemed “lollard,” have awakened intense scholarly inquiry on the part of intellectual historians and theologians but especially among scholars of Middle English literature. Indeed, lollard writing for a time nearly came to dominate a literary canon or anticanon otherwise given over to Chaucer and Langland or Julian and Margery. To a historian, lollards can appear to have become a wholly owned subsidiary of English departments, the libeled or apotheosized lollards assuming center stage—an ironic inversion which other scholars have in turn disputed, denied, or ignored. Recently we seem to have entered a season of reflection and indeed of moving on, an after phase, evident in a widely noted conference “After Arundel” and in this volume’s “Europe after Wyclif.”4 Many scholarly questions, old and new, persist: the exact connections between Master Wyclif and lollards, the degree to which Hussite positions and debates bore the mark of Wyclif’s writings, the possible relation of lollard writing to something called vernacular theology, the extent to which Arundel’s intervention remolded religious culture or language, any ripple effects of lollards on devotion and devotional writing more broadly, the character of the “lollard” Bible, what writings should be called lollard, and so on.

I readily acknowledge the continuing importance of these questions and the learning that has gone into them this last while. I come to this from another angle, however, as a historian of religious movements in the high and later Middle Ages, mostly on the continent, especially the Low Countries and German lands. I seek richer accounts of the culture and religion of the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, more variegated storylines and cultural paradigms not stuck inside rigid and antiquated notions of humanists versus scholastics, Latin versus vernacular, churchmen versus people, inquisitors versus mystics, priests versus women, orthodox versus heretical, and so on. Tensions there were in late medieval religious culture, sometimes awful ones, at times murderous ones. Still, lines were not always so simple, clear, or clean. Tensions proved creative as well as destructive, and crossovers and intersections often surprise.5 To overstate the point, and perhaps unfairly, if we insist on seeing this world entirely through a narrow version of Eamon Duffy’s thriving “traditional religion,” or just as entirely through the tight focus of heroic “dissenting lollards,” we effectively create the obverse and reverse of one and the same false coin. Moreover, the notion of “Europe after Wyclif” is itself ambiguous, perhaps intentionally so, implying both a question and an assumption, about ripples of change across Europe. The focus here will not be upon ripples of influence as such, real, imagined, or feared. Such work rests on detailed reception studies which claim considerable scholarly attention in Bohemia just now, careful and technical manuscript work that is both admirable and important. Here my question is about historical positioning, how we imagine a Europe in which lollards and Hussites in some sense fit in, not just as the paradigm for subversion or as a rebellious anomaly, but as players in a late medieval Europe all astir.

Ever since the sixteenth century, humanist and reformist punditry, sometimes allied now with reductionist approaches to social or cultural power, have conspired to turn our storylines into binaries, even among scholars who piously foreswear all binaries. We must be careful. Jean Gerson could shake his head at the visionary claims of Birgitta of Sweden but defend those of Joan of Arc, write in French or Latin as it suited, as did too Hus (Czech) and Grote (Dutch) and countless other contemporary figures. Master Gerson could act to condemn masters Wyclif and Hus, while defending the Sisters and Brothers of the Common Life against a Dominican inquisitor whom he condemned. He could expound on ecclesiastical power at length, and also lead the Council of Constance into declaring conciliar authority ancient, authentic, and binding under the Holy Spirit. He could attack simony as eating away at the integrity of the church, and yet defend the ranked enjoyment of the accoutrements of office and its privileges as essential to the dignity of those estates. Gerson was undoubtedly an exceptional personality, but his paradoxes were not so exceptional. Religious rhetoric and spiritual claims could be shrill, even unrelenting, and the more so as they moved past the complexities of all social or religious reality. In a world of amazing contrarieties, late medieval religious practice steadily complicated, layered, and nuanced the meaning and working out of these pronouncements. We must imagine people finding ways to live with such contrariety, as too those who insisted on very particular visions of what religion was or should be.

For people in the fifteenth century too, this could all prove quite bewildering. In 1383, five years into the papal schism, Master Geert Grote, founder of the Devotio Moderna, wrote a long canonistic exposition for a close friend, also a Parisian-trained cleric, answering an agonized call for advice on the rival popes. In the end Master Geert characterized his words as disordered outpourings of mind and heart which came to no clean legal resolution favoring either pope. He talked instead of overcoming his own “interior schism,” and moving in love to “gather” (congregare) a few around him into a sheepfold of Christ.6 A shorter letter to this same friend at that same time noted the “fall” and “ruin” of the church as marks of the end time, and recommended that they no longer pursue the inherited ways of worldly and worldly-wise clergymen but rather the books and truth of clergy—moving themselves to act as preachers and teachers of that bookish truth (both were deacons, not priests).7 In this same atmosphere of uncertainty Cardinal Pierre d’Ailly, along with not a few others among the learned, turned for help to prophetic revelation,8 even as they pored over law and scripture and wrote learned tractates and entered into tough negotiations, all to bring some order and understanding to a European church they found, even beyond the trying matter of papal schism, in disarray. Catherine of Siena with her followers in Tuscany and beyond vigorously backed the Roman pope, while Friar Vincent Ferrer, a preacher active in Iberia and France, firmly backed the Avignon pope, both reformers renowned for the power of their rhetoric in their native tongues.

CANON LAWYERS ON THE SHAPE OF RELIGION

If we stand back a little from literal readings of the angry or the pious pronouncements of single-minded reformers and prophets, we may seek a more panoramic view of the late medieval church, and for that we turn to lawyers. By the late fourteenth century law and lawyers, not theologians, had dominated the church and its business for over two centuries.9 This is precisely why they were so fiercely (and ineffectively) impugned by theologians, who always remained distinctly in the minority and rarely gained powerful posts (thus Wyclif and Luther, and many already before them). To grasp what these church lawyers took for granted and tried to account for, we must begin with what they presumed. Remember that in medieval society nearly all persons (small communities of Jews or Muslims excepted) were christened as babies, and by virtue of the invisible and ineradicable mark of the Lord Christ imprinted on their forehead were joined at birth to Christendom, and hereby also obligated from childhood to religious duties at once cultic, moral, and faithful. This meant church jurisdiction over dimensions of their lives we might account social—thus marriage, wills, tithes, land-bearing church claims, and more. This took in over 90 percent of Europeans (indeed down to the Reformation or the Revolution). Beyond them a smallish minority, highly privileged in religion and often in social status as well, bound themselves to a more particular rule of life by vow, and these people professed to religion had long since co-opted the word (religio) for their status and life, indeed were commonly referred to as “the religious.”

Accordingly, the term apostate referred most commonly in this era to renegade monks or nuns or friars and only occasionally to those relative few in the later Middle Ages who repudiated their baptism to join a community of Jews or Muslims. The jurisdictional claim that came with baptism could in principle still order apostates of either sort back to their previous estates, though actual practice on this account was more nuanced and varied.

Those deemed heretics too continued to fall under the church’s jurisdiction by virtue of their christening. Here coercive power was intended in principle not to torture or kill but to turn errant souls back to keeping the church’s law. Condemnation followed properly only on the persistent refusal of such persons to acknowledge the authority implicit in that baptismal mark and obediently to recant errant views or practices pointed out to them by churchmen.10 In Latin and all later medieval languages this “law” enfolded layers of meaning stretching from Scripture itself to items of belief and practice as well as its broader inherent sense of obligation—a point that masters Wyclif and Hus fully shared with the larger community, even if the term was employed by them more specifically to drive their conception of that community. Ecclesiology, how one understood the make-up of the church (though, remarkably, not yet an explicit part of Peter Lombard’s Sentences in the 1150s and hence of the required formal teaching of theologians) underlay any coherent articulation of how medieval European society and religion conjoined and indeed how the community itself was constituted. This too was a point that both Wyclif and Hus intuitively grasped (whence the importance of works on this subject in their oeuvre), as had theologians and canonists more explicitly since the battles between mendicants and seculars and then the showdown between Pope Boniface VIII (a smart canon lawyer) and King Louis the Fair (counseled by his lawyers). Still, in some sense it all rested on baptism, indeed the baptism of infants. In the eleventh and twelfth centuries several dissident groups had explicitly challenged this foundation, calling for a conscious or chosen adult baptism or blessing. Notably, too, the consecrated vows of those called religious had long since accounted in monastic spirituality as a second baptism. All this, interestingly and intriguingly, the fundamentals of christening and community, Wyclif, Hus, and other reformers and dissidents from around the year 1400 left untouched as such.

Given these presumptions, then, canonists offered a scheme that parsed the social and religious state of a Europe-wide church in a layered definition of religion. The scheme summarized here comes from Johannes Andreae (ca. 1270–1348), a Bolognese professor of law, by way of Archbishop Antoninus of Florence (1446–1459). Master Johannes, notably, had been married and spawned children inside and outside of marriage, including a daughter (“Novella”) said to help him in copying his lectures, while Friar Antoninus, an Observant Dominican in the middle of Medici Florence, authored a summa of law and theology subsequently dubbed moralis since he focused more on matters of practice than doctrine, more on jurisdiction in the internal court (confession and the like) than the external (ecclesiastical property and personnel). According to this scheme,11 widely echoed, religion referred, first and most broadly, to all who offered up that cult or worship owed the true God, thus all the christened (totam christianitatem), also called simply the religio christiana. This is a term that both Gerson and Wyclif also invoked for their own distinct purposes: Gerson especially to establish the religion of the parish (not the cloister) as basic,12 Wyclif (and Hus) to highlight his vision of a “true” parish or “congregation” as foundational.13

Second, religio referred more specially, t...