- 72 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

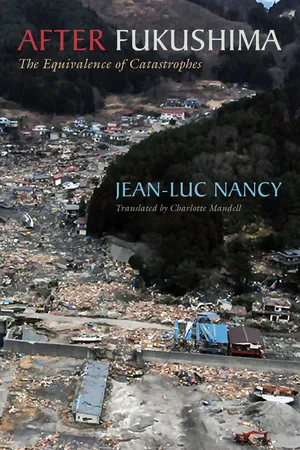

In this book, the philosopher Jean-Luc Nancy examines the nature of catastrophes in the era of globalization and technology. Can a catastrophe be an isolated occurrence? Is there such a thing as a "natural" catastrophe when all of our technologies—nuclear energy, power supply, water supply—are necessarily implicated, drawing together the biological, social, economic, and political? Nancy examines these questions and more. Exclusive to this English edition are two interviews with Nancy conducted by Danielle Cohen-Levinas and Yuji Nishiyama and Yotetsu Tonaki.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access After Fukushima by Jean-Luc Nancy, Charlotte Mandell in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Philosophy & Political Philosophy. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

“To philosophize after Fukushima”—that is the mandate I was given for this conference.1 Its wording inevitably makes me think of Adorno’s: “To write poetry after Auschwitz.” There are considerable differences between the two. They are not the differences between “philosophy” and “poetry” since we know those two modes or registers of spiritual or symbolic activity share a complex but strong proximity. The differences, of course, are those between “Fukushima” and “Auschwitz.” These differences should certainly not be ignored or minimized in any way. They should, however, be correctly understood. I think that is necessary if I want to give the question I was given a conscientious answer.

First of all, we must remember that Auschwitz has already been several times associated with Hiroshima. The outcome of what is called the Second World War, far from being conceived as the conclusion and peace that should mark the end of a war, presents itself rather as a twofold inauguration: of a scheme for annihilating peoples or human groups by means of a systematically developed technological rationality, and a scheme for annihilating entire populations and mutilating their descendants. Each of these projects was supposed to serve the aim of political domination, which is also to say economic and ideological domination. The second of the two was, moreover, linked to the first by the fact that the war of the United States with Japan entrained the one in which America engaged with Nazi Germany and also induced anxious relations with the Soviet Union.

As we know, the Nazi agenda was animated by a racist and mythological ideology that carried to its height a fury of European, Christian origin, that is, anti-Semitism (which was extended in the name of a fanatical “purity” to include the Roma, homosexuals, Communists, and the handicapped). In this respect, the Hitlerian madness was a product of Europe and is markedly different from the dominating ambition nurtured by the United States as a power conceiving of itself as the novus ordo seclorum, “the new order of the world,” proclaimed by its seal.

The fact remains, however, that Auschwitz and Hiroshima are also two names that reflect—with their immense differences—a transformation that has affected all of civilization: the involvement of technological rationality in the service of goals incommensurable with any goal that had ever been aimed at before, since these goals embodied the necessity for destruction that was not merely inhuman (inhuman cruelty is an old acquaintance in human history), but entirely conceived and calculated expressly for annihilation. This calculation should be understood as excessive and immoderate compared with all the deadly forms of violence that peoples had ever known through their rivalries, their hostilities, their hatreds and revenges. This excess consists not only in a change of scale but first and foremost in a change in nature. For the first time, it is not simply an enemy that is being suppressed: Human lives taken en masse are annihilated in the name of an aim that goes well beyond combat (the victims, after all, are not combatants) to assert a mastery that bends under its power not only lives in great number but the very configuration of peoples, not only lives but “life” in its forms, relationships, generations, and representations. Human life in its capacity to think, create, enjoy, or endure is precipitated into a condition worse than misery itself: a stupor, a distractedness, a horror, a hopeless torpor.

2

What is common to both these names, Auschwitz and Hiroshima, is a crossing of limits—not the limits of morality, or of politics, or of humanity in the sense of a feeling for human dignity, but the limits of existence and of a world where humanity exists, that is, where it can risk sketching out, giving shape to meaning. The significance of these enterprises that overflow from war and crime is in fact every time a significance wholly included within a sphere independent of the existence of the world: the sphere of a projection of possibilities at once fantastical and technological that have their own ends, or more precisely whose ends are openly for their own proliferation, in the exponential growth of figures and powers that have value for and by themselves, indifferent to the existence of the world and of all its beings.

That is why the names of Auschwitz and Hiroshima have become names on the outermost margin of names, names that name only a kind of de-nomination—of defiguration, decomposition. About these names we must hear what Paul Celan says in a poem that can, for precise reasons, be read just as easily with either of the names in mind:

The place, where they lay, it has

a name—it has

none. They didn’t lie there. Something

lay between them. They

didn’t see through it.1

a name—it has

none. They didn’t lie there. Something

lay between them. They

didn’t see through it.1

A proper noun is always a way to pass beyond signification. It signifies itself and nothing else. About the denomination that is that of these two names, we could say that instead of passing beyond, they fall below all signification. They signify an annihilation of meaning.

Here we have now the name of Fukushima. It is accompanied by the sinister privilege that makes it rhyme with Hiroshima. We must of course be wary of letting ourselves be carried away by this rhyme and its rhythm. The philosopher Satoshi Ukai has warned us about this risk in recalling that the name “Fukushima” does not suffice to designate all the regions affected (he names the counties of Miyagi and Iwate); and we must also take into consideration the traditional overexploitation of northeastern Japan by the central government.2 We must not in fact confuse the name Hiroshima—the target of enemy bombing—with that of Fukushima, a name in which are mingled several orders of natural and technological, political and economic phenomena.

At the same time, it is not possible to ignore what is suggested by the rhyme of these two names, for this rhyme gathers together—reluctantly and against all poetry—the ferment of something shared. It is a question—and since March 11, 2011, we have not stopped chewing on this bitter pill—of nuclear energy itself.

3

As soon as we undertake this bringing together, this continuity, a contradiction seems to arise: The military atom is not the civilian atom; an enemy attack is not a country’s electrical grid. It is here that the grating poetry of this vexatious rhyme opens onto philosophy: What can “after Fukushima” mean?

It is a question first of all of what “after” means. Certain “after”s have rather the value of “that which succeeds,” that which comes later on: That is the value we have given to the “post” prefix set next to, for instance, “modern” in “post-modern,” which designates the “after” of this “modern,” which is itself conceived as an incessant “before,” as the time that precedes itself, that anticipates its future (we have even known the word futurism). But the “after” we are speaking of here stems on the contrary not from succession but from rupture, and less from anticipation than from suspense, even stupor. It is an “after” that means: Is there an after? Is there anything that follows? Are we still headed somewhere?

Where Is Our Future? That is the title of a text the philosopher Osamu Nishitani wrote one month after the tsunami of March 11, 2011. It is a matter of finding out if there is a future. It is possible that there may not be one (or that there may be one that is in its turn catastrophic). It is a matter of orientation [sens], direction, path—and at the same time of meaning [sens] as signification or value. Nishitani here not only develops a political, social, and economic analysis of the situation but also questions “the civilization of the atom.”1

To this “after” I want to link the “after” of a poet. Ryoko Sekiguchi lives in Paris but maintains personal and literary ties with Japan. Under the title Ce n’est pas un hasard [It is Not a Coincidence] she published the journal she started keeping after the tsunami (starting the day before, March 10, for reasons I’ll let you discover in her book).2 On April 29 she writes: “Forty-nine days after the earthquake. This is the day in Buddhist ritual when they say the soul joins the hereafter definitively.” This note has a twofold stress: “they say” marks a distance from the belief mentioned, and “definitively,” while reporting the content of the belief, also resounds with something irremediable that no “hereafter” can console.

4

Let us start again from what these two testimonies tell us: Civilization, irremediable? Civilization of the irremediable or an irremediable civilization? I think, in fact, that the question of after Fukushima is posed in these terms. They are, moreover, more or less the terms Freud used in speaking of what he called Das Unbehagen in der Kultur, that is, less malaise or discontent in English (although both are correct translations) than mal-être (ill-being): Freud sees nothing in these other than the fact that humanity is in a position to destroy itself thanks to our mastery over natural forces.1 Freud had no idea of atomic energy when he wrote these lines in 1929. The technological methods deployed in the First World War were quite enough to give him a fore-taste of what Camus would call, after Hiroshima, the suicidal savagery of civilization.2

We might wonder if it is truly a matter of civilization in its entirety, since “civilian” use of the atom is distinguished from its military use. First, we must remember that military technologies are of the same nature as the others—they borrow from and contribute to them many elements. But we must say more and must begin by calling into question the distinction (to say nothing of the contrast) between military and civilian. We know that the concept of war has changed considerably since what were termed “the world wars” and after all the “partisan” wars,3 wars of colonial liberation, guerrilla warfare, and generally, the involvement of war—armed or else economic, psychological, etc.—in many aspects of our communal existence.

The same Osamu Nishitani could speak, on March 19, 2011, of a state o...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- After Fukushima: The Equivalence of Catastrophes

- Preamble

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- Questions for Jean-Luc Nancy

- It’s a Catastrophe! Interview with Jean-Luc Nancy

- Notes