- 328 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

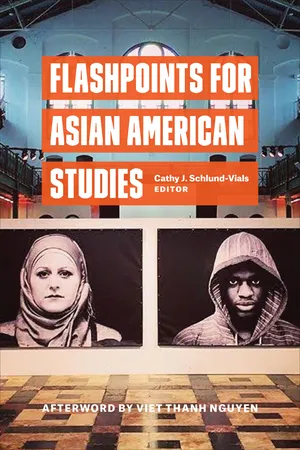

Flashpoints for Asian American Studies

About this book

Emerging from mid-century social movements, Civil Rights Era formations, and anti-war protests, Asian American studies is now an established field of transnational inquiry, diasporic engagement, and rights activism. These histories and origin points analogously serve as initial moorings for Flashpoints for Asian American Studies, a collection that considers–almost fifty years after its student protest founding--the possibilities of and limitations inherent in Asian American studies as historically entrenched, politically embedded, and institutionally situated interdiscipline. Unequivocally, Flashpoints for Asian American Studies investigates the multivalent ways in which the field has at times and—more provocatively, has not—responded to various contemporary crises, particularly as they are manifest in prevailing racist, sexist, homophobic, and exclusionary politics at home, ever-expanding imperial and militarized practices abroad, and neoliberal practices in higher education.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Publisher

Fordham University PressYear

2017Print ISBN

9780823278619, 9780823278602eBook ISBN

9780823278626PART I

Ethnic Studies Revisited

CHAPTER 1

Five Decades Later: Reflections of a Yellow Power Advocate Turned Poet

Amy Uyematsu

“Yellow Power,” circa 1969

When militant is the only way

To guarantee we can have our say—

Yellow and red, brown and black,

The times are ripe for us to strike back.

Malcolm, Mao and Ho Chi Minh

Beacons for our revolution.

Change will ferment in that furious hour

As history is witness to yellow power.

—AMY UYEMATSU

The idea of yellow power gained popularity in the late 1960s when young Asian American activists began to organize on the West Coast. Groups with names like Yellow Seed, I Wor Kuen, Asian American Political Alliance, and the Red Guard Party were forming, and the field or even concept of Asian American studies did not yet exist. Reflecting back on almost fifty years to 1969, when I wrote “The Emergence of Yellow Power in America,” I’m struck by how much Asian America has changed and yet how overall conditions of racial and economic inequality in this country have not improved. In this essay, I look back on how I came to write the yellow power article, utilizing flashpoints, quotations, and signposts that triggered key experiences and ideas. I discuss my evolution from a political activist to a poet and how being a movement “radical” in my early twenties continues to shape my thinking and writing as a now aging sansei baby boomer.

1. Flashpoint 1969

—January murders of Black Panthers Bunchy Carter and John Huggins at UCLA

—February formation of the Red Guard Party in San Francisco Chinatown

—March founding of MEChA (Movimiento Estudiantil Chicano de Aztlán)

—April publication of the first issue of Gidra, Asian American movement newspaper

To be a college student in the ’60s was like being in a nonstop firestorm. It was the decade of American revolutions—civil rights and black power, women’s liberation, ethnic studies, gay rights, counterculture. It was also the decade of a widespread anti–Vietnam War movement, with many Asian American activists taking part in peace marches along with rallies for workers’, women’s, and minorities’ rights. At the same time, there was a surge of independence struggles in Africa and the third world, including the victory of Cuban socialists in 1959. With the Cultural Revolution going strong in China, the teachings and writings of Mao Tse-Tung had a considerable impact on the American left, and many of us still have the Little Red Book in our libraries.

In 1969, the UCLA Asian American Studies Center was established along with the Center for African American Studies, Chicano Studies Research Center, and American Indian Studies Center, culminating many months of protest by mostly students of color. The first Asian American studies class, “Orientals in America,” had just been offered in the spring of ’69. Taking that class as a senior had a profound effect—I can even say it saved me—for it was the first UCLA course that truly spoke to me. With historian and activist Yuji Ichioka as our instructor, “Orientals in America” was an exciting, often rowdy, standing-room-only series of lectures, panels, and guest speakers. Yuji is now credited with coining the term Asian American, but in that first class the term Oriental was still in our vocabulary.

That same quarter I took a sociology course, “Ethnic and Status Groups in America,” which complemented “Orientals in America.” Our required reading included Black Power: The Politics of Liberation in America, by Stokely Carmichael (later known as Kwame Ture) and Charles Hamilton. Inspiration and vision seemed to be at our fingertips. We were quoting Frantz Fanon’s The Wretched of the Earth, Eldridge Cleaver’s Soul on Ice, and, of course, The Autobiography of Malcolm X. We were devouring the new Asian American monthly newspaper Gidra, joining sit-ins and coalitions, holding conferences, demonstrating against the war, crowding to hear leaders like Angela Davis, who’d just been hired (and later fired) by UCLA.

In “Orientals in America” we learned about a historical legacy of racism against Asian Americans and formed a perspective that promoted working-class and multiethnic solidarity as well as support for international struggles against imperialism. We made connections between racism practiced by the military in the killing of Vietnamese civilians and the racism Asian American soldiers faced for looking like “the enemy.” We realized that exclusionary laws against Chinese immigration were part of the same anti-Asian legal restrictions against Japanese immigrants buying land or anti-miscegenation legislation against Pilipinos. It didn’t matter if we were Chinese, Korean, Pilipino, or Japanese—we were all subject to a long-standing yellow peril mentality. Karl Yoneda, a longshoreman from the San Francisco area, spoke to our 150-plus class about labor movements and the recurring exploitation of Asian immigrant workers. He reminded us “to recognize and remember that our Yellow heritage is beautiful as is that of Blacks and Browns.”

2. With Raised Fists

“Say it loud—I’m Black and I’m proud.”—James Brown, 1968

“Yellow Power must become a revolutionary force.”

—Larry Kubota, Gidra, 1969

—Larry Kubota, Gidra, 1969

“It is a question of the Third World starting a new history of man.”

—Franz Fanon, The Wretched of the Earth

—Franz Fanon, The Wretched of the Earth

I wrote “The Emergence of Yellow Power in America” to satisfy the final course requirements for both “Orientals in America” and “Ethnic and Status Groups in America.” Between Gidra, Stokely’s book, census data, the UCLA Powell Library (when we still had to use card files), and random class notes, I pieced together a typically rushed student essay that I never guessed would still be quoted today. Looking back, I realize it took someone young, idealistic, and ignorant to how little I really knew to write a term paper making the types of claims I did. But that was the tenor of those times. Week by week, we were picking up new ideas and developing a radical political analysis. Our angry and impassioned conviction that we were fighting for justice made us eager to “spread the word.” Mike Murase published my paper in Gidra in October 1969, and the Los Angeles Free Press reprinted it soon after. That same month the new UCLA Asian American Studies Center hired me based on my article.

The term “yellow power” was a popular phrase in those early days of our movement. Larry Kubota wrote a piece titled “Yellow Power” in the inaugural April issue of Gidra. “Brown power” and “red power” were also frequently seen on march banners and in activist writings. The demand for “black power” was first raised by Stokely Carmichael and Willie Ricks of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), and in a 1966 speech, Carmichael said, “What we gonna start sayin’ now is Black Power!” Of course, it quickly became a byword and soon other nonwhite activists were bringing parallel calls into our own communities.

One of the key points I made in my 1969 yellow power paper was the difference between the potential voting strength of blacks and Asian Americans because of our being, at that time, a mere one half of one percent of the population. The nascent Asian American movement could not have predicted how much our population would jump, with the 2010 census showing 5.6 percent identifying as Asian either alone or in combination with one or more races. In round numbers, we went from 1.5 million in 1970 to over 15 million in 2010. Astounding growth, through steady immigration, with Asian American demographics going from mainly Japanese, Chinese, and Pilipino to Chinese, Pilipino, Korean, Indian, and nearly twenty other Asian and Pacific Islander groups.

In my own experience as a third-generation sansei, I’ve observed mind-boggling transformations in the ethnic profile of Los Angeles. Growing up in Sierra Madre in the late ’50s and ’60s, I recall nearby cities like San Marino and Arcadia being lily-white; now Chinese are the majority in those towns. According to a 2013 report by Asian Americans Advancing Justice, Los Angeles County is the “capital” of Asian America and home to the largest numbers of such groups as Koreans, Burmese, and Thais outside their home countries. Clearly, this is not the Los Angeles I knew. Based on our larger numbers, I see a profound difference in the way Asian Americans are treated and, more important, in the way we look at ourselves. Now we do have the voting clout that can decide elections—particularly in metropolitan areas around San Francisco, Los Angeles, San Jose, and New York City. After the 2012 presidential election, Stewart Kwoh, who heads the Asian Pacific American Legal Center (APALC), stated, “The Asian-American vote is becoming more important. We are the fastest growing racial group from 2000–2010, there are over 18 million in the U.S. now.”

My yellow power article also discussed economic disparities within the Asian America of the late sixties. Many of us activists were from middle-class and working families, but we were concerned about unaddressed poverty, drug use, and delinquency in our communities and, inspired by the example of the Black Panthers in Oakland, tried to develop our own Serve the People programs. The so-called “successful” Asian American image continues to be reflected in higher incomes and educational levels, particularly for Chinese and Indians, but a less known fact is that Koreans, Thais, Cambodians, and Hmong have lower median earnings than the general population. Without access to data, I wrote in my student paper about “continuing racial discrimination toward yellows in upper-wage level and high-status positions.” The glass ceiling that we knew existed has not changed significantly; despite our incredible educational attainment, there are still few Asian American executives, college presidents, and managers in a society that only allows us to rise so far, held beneath what some term the “bamboo” ceiling.

Asian American activists of my era rejected the image of the “silent, passive Oriental.” We repudiated the stereotype the majority culture cast on us but were also critical of the “Uncle Tomism” we sometimes saw in our own communities. If I were to change one thing in my yellow power paper (and there are many areas I could revise), it is in my discussion of the supposedly quiet, fearful Asian American. We have suffered centuries of racial injustice in this society, and like other people of color, we have responded with courage, self-respect, and resistance. As early Asian American studies began to uncover our histories, both past and current, we were seeing case after case of Asians speaking out and fighting back. Pilipinos who helped to build the United Farm Workers. Young Nisei in concentration camps, the “no-no” boys, who were jailed for refusing to join the military and swear allegiance to the U.S. Chinese railroad workers who went on strike in the 1800s. Issei communists who played crucial roles in the West Coast workers movement. Coalitions between Chinese, Pilipino, and Japanese communities in Seattle to fight bills that would make interracial marriage illegal. Of course, none of this was covered in our history textbooks—we had to dig up this info ourselves. It became clear that we and other minorities have to write our true histories.

3. Gettin’ It Done Collectively

“This isn’t one of those blonds that anyone can pick up in a supermarket.”

—Title to the preface of Asian Women, U.C. Berkeley, 1971

—Title to the preface of Asian Women, U.C. Berkeley, 1971

“These are critical times for Asian Americans and it is imperative that their voices be heard in all their anger, anguish, resolve and inspiration.”

—Franklin Odo, preface to Roots: An Asian American Reader, UCLA, 1971

—Franklin Odo, preface to Roots: An Asian American Reader, UCLA, 1971

As Asian American ethnic studies programs began appearing on college campuses, particularly in California and the East Coast, there were few books or articles that could be used in our classes. To fill the gap, two of the earliest publications were published in 1971 by Asian American activists at Cal and UCLA. Both books utilized existing historical articles along with new pieces on contemporary issues, interviews of community leaders, photos, and poetry.

At U.C. Berkeley, a women’s collective put out Asian Women. A remarkable compilation of writings about Asian women both here and overseas, it reflected the broad internationalist perspective so many of us were embracing, including coverage of the 1971 Indochinese Women’s Conference in Vancouver and essays on Arab and Iranian women.

In those infant years of Asian American studies, we enjoyed a certain level of freedom in how we developed our classes and programs. I was on the UCLA staff from 1969 to 1974 and did everything from being a teaching assistant to developing new courses, organizing students, and coordinating center publications. Roots: An Asian American Reader grew from two volumes of mimeographed articles we’d stapled together for our classes in 1970. We needed a textbook, so an editorial team consisting of Franklin Odo, Eddie Wong, Buck Wong, and myself (under my then married name, Tachiki) produced Roots. Our intent was to provide an eclectic collection of existing articles, movement documents (such as the twelve-point platform of I Wor Kuen), and new interviews, as well as a survey of existing Asian American literature of that time. We included poems by writers like Al Robles as well as by students. Roots was a collective effort of center staff and students—editors, designers, photographers, typists, and a distribution team. I recall weeks of typing up text on IBM Selectric typewriters, then laying out the articles, photos, poems, and documents on white pasteboard. Long before computers or copy machines were standard college office equipment, we were using carbon paper so we would have a duplicate. Published in 1971, Roots went through twelve printings and eventually sold about fifty thousand copies for the UCLA Asian American Studies Center.

It is gratifying to see how much the field of Asian American studies has flourished. According to Cathy Schlund-Vials, 2017 President of the Association for Asian American Studies, programs and departments exist at over forty colleges. Masters and doctoral dissertations related to Asian American studies or work focused on aspects of Asian America number in the tens of thousands.

When I was in high school, there was no mention of American concentration camps in my textbooks. Now there are not only history books but biographies, novels, plays, children’s stories, and memoirs about the incarceration. Brian Niiya, staff member of Densho: The Japanese American Legacy Project, estimated in 2016 that camp publications number around five hundred (with this total not including films, museum exhibitions, or scholarly articles and papers). Back in 1965, my Pasadena High classmates in a twelfth-grade civics class would not believe me when I told them my parents and grandparents were sent to the camps after Pearl Harbor. Now books like Farewell to Manzanar appear on required reading lists. And recently, my eight-year-old yonsei grandson told me his class celebrated January 30, Fred Korematsu Day, with an all-grades assembly.

4. Aiiieeeee and More

“Think Yellow! … with liberty or chopsticks for all.”

—Lawson Fusao Inada, Before the War

—Lawson Fusao Inada, Before the War

“As a poet I’ve followed the f...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Introduction: Crisis, Conundrum, and Critique

- Part I: Ethnic Studies Revisited

- Part II: Displaced Subjects

- Part III: Remapping Asia, Recalibrating Asian America

- Part IV: Toward an Asian American Ethic of Care

- Afterword: Becoming Bilingual, or Notes on Numbness and Feeling

- Acknowledgments

- List of Contributors

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Flashpoints for Asian American Studies by Cathy Schlund-Vials, Cathy J. Schlund-Vials in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Literature & Literary Criticism Theory. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.