![]()

CHAPTER 1

Prosthetic Objects

On Sigmund Freud’s Ambivalent Attachments

Following the surgical removal of much of his jaw at the age of sixty-seven, Sigmund Freud endured the implementation of multiple prostheses for the remainder of his life. Freud’s sixteen-year cancer burden and drama of prosthetic adjustment demonstrates the way in which cancer and its treatment destabilizes its sufferer’s experience of corporeal and psychic cohesion.1 Cancer and its treatment render survival a product of relentless maintenance and adjustment. Freud’s prolonged cohabitation with what he referred to as “my dear old cancer” is characterized by a state of persistent ambivalence resulting from dependency upon an object that both preserves and impairs his bodily and psychic integrity.2 His affectionate moniker, intended with sarcasm, nonetheless highlights the ongoing conflict generated when one becomes attached to objects that simultaneously sustain and work against one’s life. Psychically, these prosthetic attachments are to Freud horrific monsters at once loved and hated, despised yet needed.

Prosthetic objects substitute for the objects Freud lost to cancer, and the prosthetic condition can be understood as a technological predicament in which technology both repairs and dehumanizes the body. Because of its capacity to disturb the boundaries between the human and nonhuman, the prosthesis introduces questions as to how one determines self from what is foreign to the self. Freud’s prostheses strikingly and painfully materialize David Wills’s concept of “dorsality” as that which turns the human into a technological thing.3 Dorsality presumes that technology and humanity are utterly imbricated. Technology is brought into being at the moment a human comes into the world such that the human could itself be considered technology, “a technology that defines and so produces the human.”4 Wills’s description of this technology resembles the work of cancer; it “proliferates or mutates.”5 Freud’s cancer-ridden body models a “mutual dependence between the flesh and machine” that comes to characterize contemporary posthuman techno-bodies in which, as Braidotti affirms, the “technological construct now mingles with the flesh in unprecedented degrees of intrusiveness.”6

Freud’s case also shows how the prosthesis resembles the pharmakon, which Derrida explains is a drug or medicine that acts as both poison and remedy.7 For Derrida, the pharmakon presents a fundamental ambivalence that intrudes upon the body of discourse. Freud’s “chemical prosthesis,” the nicotine to which he was addicted, exemplifies the paradox of needing and gaining pleasure from that which endangers one’s life. Smoking, which imperiled his health, fueled Freud’s creative production, allowing him to psychically resist the destructive forces of cancer and death. According to Freud’s formulations, the life drives that impel creativity and integration are pitted against the death drives. Within Freud’s “autothanatography,” his public and private writing of his own death, the disintegrating effects of cancer manifest in the death drives.8 I argue that cancer and psychoanalysis can be productively thought together to detect the work of “not-death,” my reading of Freud’s concept of the death drive. “Not-death,” as I conceive of it, is a paradoxical entanglement of the life and death drives and a mode of survival. Freud proposed that one’s own death is unrepresentable to oneself. As if to compensate for this unconscious negation, Freud’s embattled struggle with prosthetic attachments can be seen as mediating his relationship to his mortality, both representing death and warding against it.

The Prosthetic Contest Between Human and Nonhuman

In April 1923, Sigmund Freud detected a lesion in his mouth. When it worsened, he consulted two friends, Felix Deutsch, an internist, and Maxim Steiner, a dermatologist. Although malignancy was already evident, both physicians hid this from Freud, diagnosing it as “leukoplakia,” a premalignant lesion. After a botched and inadequate surgery performed by Marcus Hajek, yet another doctor who failed to inform Freud of the malignancy of his tumor, Freud suffered a severe hemorrhage from his mouth on a night train to Rome. When he returned to Vienna, he was finally put in the hands of a surgeon who would unflinchingly perform the radical surgery required for the gravity of the situation. Hans Pichler removed so much tissue and bone that he left a gaping hole in Freud’s mouth, necessitating a prosthesis for the most fundamental activities that sustain life: eating, speaking, and, perhaps most important for Freud, smoking. The pathological results were squamous cell carcinoma of the hard palate, a cancer associated with a low survival rate.9 Had Pichler been more conservative, as his predecessor had been, Freud would likely not have survived as long as he did. Freud’s prolonged survival from his diagnosis at the age of sixty-seven to his death at eighty-three is impressive even by contemporary standards, and it resulted from an unusually vigilant surveillance on the part of Pichler, Max Schur, who was to become Freud’s personal physician, and his primary caregiver, his daughter Anna. Together they succeeded in keeping Freud cancer-free for the next decade and a half.

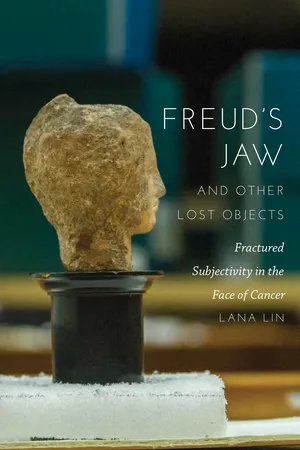

Figure 1. Freud’s prostheses, Freud Museum London, 2013. Photograph by Ardon Bar Hama.

In 1924, Pichler consulted with Freud seventy-four times; in 1932 he saw him ninety-two times.10 Over the course of thirty-three surgeries, ten prostheses, and countless examinations, Pichler took exacting surgical and consulting notes.11 These notes convey an overwhelming feeling of exhaustion, of the arduousness of maintaining life, of the chronicity of adjustment. To this point, Freud’s biographer, Ernest Jones, provides a rationale for relegating excerpts from Pichler’s notes to the appendix of his mammoth three-volume biography: “Even for faithful admirers the repetition about the prosthesis must become boring.”12 Indeed much of the chronicle of Freud’s lengthy illness consists of an extended embattlement with what Jones describes as a “a sort of magnified denture or obturator . . . a horror; it was labelled ‘the monster.’ ”13 “Horror” aptly names the genre that befits Freud’s grueling saga, the genre that Christina Crosby likewise selects following her catastrophic accident when she compares living with disabling incapacity to a horror story that excites fear beyond reason.14 In Freud’s story, the prosthesis is the horror that incites fear and pain, yet it also delivers him from starvation and silence. Crosby and Freud must adapt to horror that becomes mundane, horrors whose constant recurrence is both diabolical and enervating. The prosthetic maneuvers in defiance of cancer’s potential recurrence are deadening in their repetition, arousing uncanny conflicts in Freud’s state of mind. After nearly four years of unrelenting procedures, Pichler succinctly comments on Freud’s ambivalence: “Patient reports some interesting self-observations on the ingratitude of patients and rebellion against dependence.”15

Pichler initiated his treatment notes on September 26, 1923, describing the first major and most extensive operation that he was to perform to extricate the cancer from Freud’s mouth. It was to be a radical operation in two stages, removing much of the upper right hard palate, right jawbone, submandibular lymph nodes, right soft palate, cheek, and tongue mucous membranes. The operation required weakening the mandible to permit it to be removed, along with the upper jawbone.16 The ghastly violence of the procedure was accentuated by its being rehearsed on a corpse in order to test its feasibility. The manipulation of an inanimate body serves as evidence for the surgical possibilities of the animate body; the knowledge gained from the inanimate informs the surgeon about the workings of the animate.

This preparatory investigation indicates a codependence between the animate and inanimate that persists throughout the course of a human life and its aftermath. Life-threatening illness compels the afflicted subject to confront the necessary entanglement between what one considers one’s own body and foreign “others.” The illusion of the independent unified body is exposed as the sufferer is thrown back to her psychic prehistory when she was nothing but an amalgam of disconnected partial objects, those psychic equivalents of anatomical parts, such as a mouth, a breast, a thumb. This process of disunification characterizes not only the experience of the patient but can be perceived in, and is perhaps even provoked by, the attitude of the attending doctor. Pichler writes in the traditional detached manner of a surgeon, as if he were talking about a collection of anatomical parts rather than an integrated human being: “Cut through the middle of the upper lip, then around the nose till half height. . . . Then opened the jaws.”17 As paternal as the doctor might seem to be, he is better likened to the mother in Lacan’s mirror stage scenario. In Lacan’s description the mother or some other prosthetic support holds the infant up to the mirror and in recognizing the unity of her child might be said to hold her child together.18 In contrast to this “good mother” (in Melanie Klein’s terms), the surgeon is experienced as akin to Klein’s “bad mother,” whose persecutions fragment the intact body into an assortment of parts—lip, nose, jaw.19

A prosthesis exemplifies the powerful attachments humans have to material objects that are not strictly human. Used to replace a lost anatomical part, a prosthesis serves as a kind of material memory. Freud’s jaw prosthesis was a material trace of the presence and absence of his mouth, made from an impression of his teeth and mouth cavity. What is most striking in reading through the two-hundred-page transcription of his medical case history is the chronic adjustment required of the prosthesis because of the changing conditions of his mouth. The impossibility of a prosthesis to ever fully substitute for a lost part is due to the fact that the prosthesis cannot itself adjust to changing conditions in the way that human tissue can. Living tissue is characterized by its adaptability and constant change, that it can never be static unless it dies. This is of course what makes living substance vital and animate, and a prosthesis, at least as of the twentieth century, is inanimate. Yet a prosthesis is not a thing like any other thing. It tends to be made by hand, rather than mass-produced. Its nonuniversality is the result of the fabrication skills of a prostheticist in ongoing rapport with a surgeon and a patient. It might be more accurate to consider the prosthesis a process or even a condition as opposed to a contained, inanimate thing.

While Freud’s prostheticist was also his surgeon, his prosthetic management involved mutuality amongst many bodies besides his own, including numerous specialists and caregivers. The singularity and hybridity of the prosthetic object arises from this set of relations. The prosthesis participates in a reciprocal relation of care—it cares for its owner and must in turn be cared for. Perhaps this is one reason that the prosthesis seems to exercise a kind of agency that sets it apart from other inanimate things. The owner of a prosthesis becomes intimate with it through physical and emotional attachment. It is frequently indispensable because it performs a function necessary to everyday life. The owner obtains a familiarity with it through habitual use. It is usually worn in a relation of physical proximity that needs to be managed.20 Biophysicist and engineer Hugh Herr reports, “The connection between the artificial limb and my body isn’t that secure.”21 That Herr uses the word “secure” underscores not only a physical but also an emotional connection.

With the prosthesis, as with love objects, one seeks a secure attachment, and yet it cannot be too close. One requires a “good enough” attachment, to use D. W. Winnicott’s lexicon, as in a “good enough mother.”22 For Freud this meant that his prosthesis should close enough so that he could speak but open enough to allow him to eat and smoke. Furthermore, it not only served these essential activities but provided support for his other organs and bodily appearanc...