![]()

1

SELFLESS DESIRES

SACRIFICIAL AND SELF-FULFILLING SERVICE TO OTHERS IN CASABLANCA (1942), THE BELLS OF ST. MARY’S (1945), AND THE INN OF THE SIXTH HAPPINESS (1958)

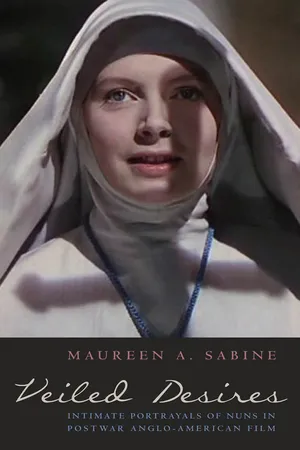

When Ingrid Bergman appeared on-screen as Sister Mary Benedict in The Bells of St. Mary’s, she was already a major film celebrity, but she made the film nun herself a star who “light(s) up dark lives … with luminous Hollywood beauty” (Loudon 1993: 16). The movie reviewers in 1945 felt that Bergman succeeded in representing the Catholic nun to a modern audience as an attractive, appealing, and admirable figure. Yet by the end of the century, actual nuns had come to take a dim view of her film performance as Sister Benedict and to lament her role in typecasting them as “perpetual little girls who combined a rarified ‘Bells of St. Mary’s’ faith with a wide-eyed naivety” (Schneiders 2001: 234). How did Sister Benedict go from being a role model to a caricature, the charming and youthful face of the modern nun to an old and outgrown likeness?

Today’s nun is no Ingrid Bergman playing Sister Benedict to Bing Crosby’s Father O’Malley in some kind of real-life version of “The Bells of St. Mary’s.” Today’s nuns are mature and independent in ways they never were before, and they carry a heightened awareness of themselves as women and as Catholics. (Deedy 1982: 12)

In the post–Vatican Council II era of review and reform, Bergman’s Sister Benedict became easy target practice for the exponents of “today’s nun.” Yet a moderate like Dominican Sister Maria Christine recalls that when religious life was shaken by turbulent change and reform in the late sixties, Hollywood classics like The Bells of St. Mary’s sustained her conviction as a young woman that she might nonetheless have a religious vocation (2008: 51). One reason Bergman’s Sister Benedict is held up as both a beau ideal and discredited screen image of a nun is that she shows how the lives of twentieth-century women religious were shaped by the tension between the beliefs of traditional religion and the progressive assumptions of modernity. How, to cite a venerable paradox, was the nun to work in the modern world but give witness to spiritual values that were not of this world? Following on from this paradox, I will explore how and why The Bells of St. Mary’s is ambivalent about its nun protagonist, uncertain whether Sister Benedict’s vivid lifeforce is an impediment or boost to her religious life, and whether her vows call her to choose between self-sacrifice as a religious and self-fulfillment as a woman.

For the traditional nun, a vocation does not arise as a result of her personal efforts, merits, and achievements. It is a mysterious gift from on high prompting the answering gift of self-surrender and “obedience to God, without any thought of reward” (Nygren 1953: 95). The Church exalted this whole-hearted offering of self as a divine expression of love and as the most perfect realization of the religious call to follow Christ. In theory, a life consecrated to the vows of poverty, chastity, and obedience frees the nun “to love God with an undivided heart” (Donovan and Wusinich 2009: 26, 29, 36). However, film nun Sister Benedict dramatizes the heartache that a modern woman religious could experience as she struggles to reconcile her commitment to agape as pure, selfless love and service for God with desires traditionally deemed more worldly, self-seeking, and stirring, which go by the name of eros. An early scene of The Bells of St. Mary’s illustrates the implicit conflict between agape and eros. Father Chuck O’Malley introduces himself to the nuns in his new parish. His tone is light but his intention is solemn. He expects to edify, console, and uplift an appreciative convent audience.

St. Mary’s has been here a great many years and has seen the labors of a good number of the sisters of your order and I know that the work hasn’t been easy. In the eyes of the world, very few even take notice of us, but earthly honors and rewards are not for you. You’ve sent forth generations of pupils who have been a credit to the teachings inculcated here. St. Mary’s has grown old doing good.

As the priest warms to his homily on agape and the centrality of unseen and unappreciated service in the lives of teaching sisters, there is a reaction shot of the convent superior, Sister Benedict. It registers the faint quiver of her lips in amusement when O’Malley moralizes that “earthly honors and rewards are not for you,” and wry exchange of glances with her fellow sisters when he concludes that “St. Mary’s has grown old doing good.” As he proceeds to discuss the work of a parish priest, the nuns begin to titter until they are all laughing outright at what he says. O’Malley looks disconcerted rather than affronted. While he speaks, the camera lets the audience in on the joke with a medium shot that takes in the convent cat playing with his straw boater on the mantelpiece behind him. He cannot see either visually or metaphorically why the nuns might find him funny. Other than the fact that he is upstaged by a cat, do they think it rich that a priest who is still something of a man about town, who had contact with his old girlfriend in Going My Way, and who did not renounce his love for jazz or popular music when he became a Catholic priest should be lecturing them on the virtues of self-sacrifice? Are they entertained by his tacit message that they—like St. Mary’s—are antiquated and old-school? If the priest is oblivious to the fact that he has compared them to old girls, the nuns show a sense of humor that makes him look like a maladroit schoolboy. The mise-en-scène establishes the fact that the women religious who serve St. Mary’s may espouse the traditional belief that submission to God and Church-appointed superiors “exemplifies an interior freedom born of mature self-surrender” (O’Brien and Schaumber 2009: 200), but this does not make them submissive pushovers. It also suggests to film viewers that they should look with greater acuteness than the priest at how the sisters regard themselves, their work, and their calling in The Bells of St. Mary’s.

Introduction

The priest’s theme of noble sacrifice and selfless service animated Christian worship, motivated religious vocations, and justified missionary evangelism and expansion. However, the ideology of self-sacrifice has been influential not only in the construction of the Christian ideal of love and the core purpose of religious life but in the institutional definition of femininity. It was the natural duty of Christian women to subordinate their personal desires to the needs of others. It was the God-given imperative of women religious to efface themselves in service so that “few even take notice of us,” and to deny the “earthly honors and rewards” that not only fund churches and schools but build self-worth and a sense of achievement. Religious thinkers now question the fundamental contrast that theologian Anders Nygren drew in the thirties between agape and eros, and argue that it led to a false dualism in which selfless altruism is valorized while personal desires are denigrated as selfish and egotistic. Nygren’s comparative study would later make the self-sacrifice and the self-giving sanctified in religious life and the self-knowledge, self-development, and self-fulfillment promoted in secular feminism seem contrary ideals (Nelson 1979: 110–17 and 1992: 34–5; Miles 1998: 125). His theological representation of agape as wholly opposed to eros certainly did not make it easier for nuns in the mid-twentieth century to resolve the conflict they felt between traditional religion and progressive modernity. The question I pursue through an examination of Ingrid Bergman’s portraits of devoted service to others in Casablanca, The Bells of St. Mary’s, and The Inn of the Sixth Happiness is to what extent women with a religious calling are presented as gaining power through and over the ideology of self-sacrifice to achieve their own desires (Hunter 1984: 36, 89).

The theme of sacrifice for a higher cause also resonated with “the homefront heroine(s)” who flocked to the cinema to see Bergman in the wartime film Casablanca (Orsi 1996: 55). At the end of the war, American Catholics would be captivated by her portrait of religious devotion to an inner-city parochial school in The Bells of St. Mary’s even though they were moving out of the old parishes in urban immigrant neighborhoods. In the late 1950s, a cold war audience, pondering the fate of Christian missionaries who disappeared in communist China, would be inspired by her spirited interpretation of the altruistic reformer Gladys Aylward in The Inn of the Sixth Happiness (Sanders 2008: 137–9). Ingrid Bergman, radiant in her renunciation of romance, sexual fulfillment, native home, or natural family in this film triad, reflects an ideal of untiring, selfless femininity that appealed to the popular imagination not only of the Catholic immigrant community with its ethos of sacred lowliness and sacrifice, but war-scarred America from the 1940s through to the end of the 1950s (Burke Smith 2010: 6; Gordon 1994: 592; Gandolfo 1992: 3–4, 47; McLeer 2002: 83–4). Furthermore, the spiritual maternalism that she brought to the role of Sister Benedict as school principal and teacher also had the official approval of Church authorities who later defined the nun in the modern world as someone who “ha(s) given up the possibility of a family of (her) own in order to be at the disposal of all families and to devote to them (her) most loving care and solicitude” (Suenens 1963: 16, 127).

Father O’Malley believed that the world took little notice of nuns’ work at St. Mary’s. Historically, however, women religious had left a visible trail across America in the Catholic schools, hospitals, social agencies, convents, and mother houses they had founded and operated since the nineteenth century. More often than not, it was the priests in charge of the parishes and the fundraising that financed brick-and-mortar Catholicism who took their services for granted and did not recognize them as the pillars of the working Church (Weaver 1995: 36). As movies shaped the national consciousness in the twentieth century, the women religious who helped build the service infrastructure of America also began to appear on-screen, first in silent pictures such as Pieces of Silver (1914), The White Sister (1915), Naked Hearts (1916), The Worldly Madonna (1922), and a celebrated remake of The White Sister (1923), starring Lillian Gish, by the Catholic director Henry King. In 1933, a sound version of The White Sister debuted for the third time, featuring Helen Hayes who would later play opposite Ingrid Bergman in Anastasia (1956) (Weisenfeld 2008: 39–40; Butler 1969: 89). These films recycled nineteenth-century Romanticism’s trope of the nun as a beautiful, trapped figure of erotic pathos (Mourao 2002: xviii, 1–2, 53–5). Even Henry King’s 1943 film The Song of Bernadette—which honored Catholic popular belief in the intercession of the saints and the apparition of the Virgin Mary at Lourdes—continued to stereotype the nun as a tragic victim by depicting the young visionary Bernadette Soubirous as coerced into entering the convent and cruelly treated once there. Only a year afterwards, however, The Keys of the Kingdom (1944) broke this mold and looked forward to Bergman’s more affirmative film representation of a religious calling by giving a supporting part to a missionary nun who works in partnership with a priest in early twentieth-century China during and after the republican revolution.

Ingrid Bergman

Ingrid Bergman brought Sister Benedict alive on-screen as a nun of great energy, deep feeling, warmth, and charisma, a woman who became a religious because she desired something more in life. Those who now dismiss her performance as that of a “luminous Hollywood beauty” miss the brilliance that the first film critics saw in her as a young actress. Again and again they marveled at how she lit up a part from within. The New York Times reviewer Frank Nugent put his finger on her mystique when he described “that incandescence about Miss Bergman, that spiritual spark which makes us believe that Selznick has found another great lady of the screen” (October 6, 1939: 31; Spoto 2001: 91). Cultural critics who have recently studied Bergman’s star image note the contradictory way in which both movie fans and critics attributed spiritual qualities to an on-screen persona that often exuded sexuality, and how the actress suffered after her extramarital behavior off-screen exposed these contradictions to public scrutiny and censor (Damico 1991: 244–52; McLean 1995: 38–49). The underlying binary assumption of these perceptions is that sexuality and spirituality are in conflict with one another. Yet Bergman used her beauty—which critics invariably referred to as shining, radiant, or luminous—to express an ardor that dissolved this opposition and pointed to the indivisibility of the body and soul. Indeed the source of Bergman’s brilliance as a performer lay in her talent for plumbing erotic depths, what Audre Lorde called the capacity to “live from within outward, in touch with the power of the erotic within ourselves, and allowing that power to inform and illuminate our actions upon the world around us” (1984: 58). As my study of Bergman’s performances in Casablanca, The Bells of St. Mary’s, and The Inn of the Sixth Happiness will show, her characters brought this erotic radiance to their relationship with others whether it was through love-making, service, self-sacrifice, prayer, or devotion (Beattie 2006: 15). Indeed when Sister Benedict speaks of the “complete understanding” that is necessary for a young woman to have before she can say whole-heartedly “I want to be a nun,” she is intimating that a religious vocation understood as agape is incomplete without knowledge and appreciation of other forms of desire.

In 1939, Ingrid Bergman was a popular Swedish film actress who had just arrived in Hollywood to reprise a role that would bring her international attention as Anita Hoffman in Intermezzo. Bergman’s new Hollywood boss, David O. Selznick, later remarked that “the minute I looked at her, I knew I had something. She had an extraordinary quality of purity and nobility and a definite star quality that is very rare” (Feldman and Winter c. 1991), qualities that would make her perfect for the leading role of Sister Benedict. However, Bergman refused to undergo the radical studio makeover or change of name that turned actresses into screen goddesses, but that ironically required an obedience to the Hollywood star system parodying that of a postulant in a strictly run convent. Selznick artfully capitalized on her initial resistance by crafting a natural image for the actress that emphasized the unspoiled and wholesome impression she first made. She later recalled, “I looked very simple, my hair would blow in the wind, and I acted like the girl next door” (Spoto 2001: 70).

Bergman made her first appearance in Hollywood just before the start of World War II, when film actresses were one of the few groups of women who—like nuns in active service—had a profession and prospects. The star dedicated herself with characteristic single-mindedness, application, and stamina to her acting career but in doing so, did not conform to the socially approved gender ideal of primary devotion to marriage and motherhood. As she later admitted with an unflinching honesty that reflects a brutal capacity for self-examination, “My whole life has been acting. I have had my different husbands, my families. I am fond of them all and I visit them all, but deep inside me there is the feeling that I belong to show business” (Spoto 2001: 397). Bergman’s workaholic drive informs her film portrayal of Sister Benedict and will characterize other nuns on-screen such as Sister Clodagh in Black Narcissus (1947), Sister Luke in The Nun’s Story (1959), Sister Michelle in Change of Habit (1969), Dame Philippa in In This House of Brede (1975), and Sister Aloysius in Doubt (2008). Her comment that “deep inside” she felt she belonged to show business is an insight into someone who had a consuming desire to be an actress. As theologian David Carr rightly points out, “There can be a deeply erotic dimension to work that coincides with what is deepest in ourselves” (2003: 35). Unfortunately, Bergman’s indefatigable careerism would not always be viewed sympathetically by a conventional film audience. Her Hollywood rise to stardom coincided with a war period...