![]()

1

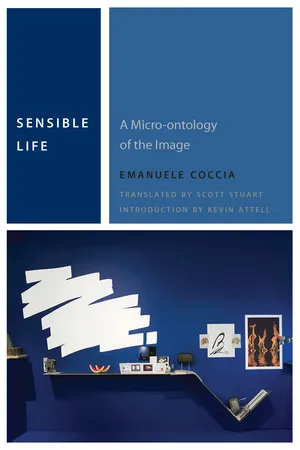

SENSIBLE LIFE

It happens even when our eyes are closed or when all our senses seem to be shut to the outside world. If it is not the sound of our own breathing, then it is a memory or dream, tearing us away from our seeming isolation and submerging us once again in the sea of the sensible.1

We like to imagine ourselves as rational beings who think and speak, yet to live means first and foremost to look, taste, feel, and smell the world around us. We can live and know how to live only thro ugh the senses, and not simply to have knowledge of what surrounds us: Sensation [sensibilità] is more than a cognitive faculty. Our very own body is, in all respects, sensible. We are sensible to the same extent and intensity with which we live from and within the sensible: We are for ourselves and can only be for others a sensible appearance. Our skin and our eyes have color, our mouth has a certain taste, and our body continuously emits lights, odors and sounds as it moves, speaks, eats, and sleeps.

We live from the sensible, but this is not a question of simple physiological necessity. In all that we are and all that we do, we have dealings with the sensible. Our daily bread is not a sum of principles that nourish us but an infinite spectrum of tastes, a reality that exists solely in a precise palette of colors and temperatures. Only through the mediating gleam of our sensible imagination we do have access to our past and our future. Moreover, we relate to ourselves not as we relate to an incorporeal, invisible essence but as to something with sensible consistency. We spend hours every day altering the natural fragrances, shapes, and colors of our body as well as of the world that surrounds us. We want exactly that fabric, that cut, that color and pattern. We go to great lengths to ensure that certain, specific smells predominate within the spaces we inhabit. We trace signs on our skin, our faces and our bodies. We color around our eyes and paint our nails—as if we were dealing with brands, effective talismans upon which our futures depended.

This is no narcissistic obsession: Caring for the world in which we live means caring for its sensible structure. We relate to the world not through an act of immaterial contemplation, nor through a pure practice. Our relationship with the world is a sensible life: an uninterrupted production of sensible realities made of sensations, odors and images. All that we create and all that we produce is made of sensible matters—beyond our own words, it is the tissue of the things in which we realize our will, our intelligence, our most violent desires and most disparate imaginations. The world is not simply extension; neither is it a collection of objects, and it cannot be reduced to an abstract possibility of existence. To be in the world means, before anything else, to be within the sensible, to move within it, to make and unmake it without interruption.

Sensible life is not only what the senses stir within us. But it is also the manner in which we give ourselves to the world, the form that allows us to be in the world (for ourselves and for others), and the way in which the world becomes understandable, accessible, and livable. Only in sensible life is a world given to us, and only as sensible life are we in the world.

![]()

2

MAN AND ANIMAL

According to tradition, sensible life is not exclusively a human trait. On the contrary, sensation has always been considered to be the faculty through which “living things, in addition to possessing life, become animals.”1 Through the senses, we live in manner indifferent to our specific difference as humans, as rational animals: Sensation gives form and reality to that which, in our life, is not specifically human.

According to the same tradition, sensible life is that particular faculty which allows certain living beings—animal life in all its forms—to relate to images, where for images we understand broadly all forms of the sensible world, whether they be visual, smelling, or auditory. Sensible life is the life that images themselves have sculpted and made possible. Every animal is a particular form of opening to the sensible, which is to say a certain capacity to appropriate and interact with images. “Just as the vegetative faculty requires food to be active, so the sensible faculty likewise requires the sensible,” writes Alexander of Aphrodisias.2 If the sense faculty is that which gives a name and a form to all animals, then images play a role not dissimilar to food in defining the way in which each one lives. Life requires the sensible and images in the same way it requires nourishment. The sensible thus defines the forms, the realities, and the limits of animal life. In order for life to exist, in order for it to be given as experience and as a dream, “it is necessary that the sensible exists.”3

Inquiring after the nature and the forms of existence of the sensible allows one to fathom the conditions of possibility of life in all its forms, human and animal. The distance that separates human life from the rest of animal life is, in fact, not an unbridgeable abyss that separates sensibility from the intellect or the image from the concept. A large part of the phenomena that we call spiritual (whether we mean dreams or fashion, speech or art) not only presupposes some form of commerce with the sensible, but is made possible only by the capacity to produce images and to be affected by images. Between man and animal there is only a difference of degree, not of nature: That which makes man human is only the intensity of the sensation and of the experience, the strength and the effectiveness of images on our life. The sensible in which we live and are worldly beings is not assigned to us like an irrevocable destiny. We do not have one single coat, one single voice, one single expression; the lights, sounds, and odors through which we are given to the world can change at any instant. The relation to the sensible, which we ourselves are, the relation to the phantasm that we embody is always poetic, it always requires the mediation of a doing, of individual and collective techniques.

Barely fifty years ago, Helmuth Plessner could still believe that the enigma of “what specific possibilities man derives from his senses, those to which he may trust and depends on” as one waiting for a solution. His project of an “esthesiology of the mind”—which was then more precisely defined in the a context of an “anthropology of the senses”—should in fact be inverted; rather than ask for the specific possibilities that man derives from his senses, we need to know what form sensible life can have, for man as for animals.4 In man and in his body, what is the sensible capable of? How far do the power, activity, and influence of sensation go in human activity? Moreover, what is the stage of sensible life, what is the modality of this life of images, which we are accustomed to calling “man”? This dialectical inversion does not consist in simply a change of our point of view. Rather, it is a matter of not presupposing a human nature beyond the powers that define it.

In order to understand “what specific possibilities man derives from his senses, which he may trust and depend on” we must resolve a double enigma. First, it will be necessary to examine the mode of existence of what we call sensible. Such is the task assigned to the first part of this book. But if sensible life does not necessarily have human origins (without yet being foreign to man), the science of the sensible—and by an easy syllogism the science of the living—has a vaster and more general scope than a simple anthropology. The science of the sensible may be articulated only in terms of a physics of the sensible.

On the contrary, an anthropology of the sensible is not concerned with the way in which images exist in front of a human subject, who is endowed with senses. Instead, it must study the manner in which the image and the sensible give body to activities of the spirit and give life to man’s own body. It is to this requirement that the second part of the book attempts a response.

![]()

3

INTENTIONAL SPECIES

With the onset of modernity, a strange fate weighs on sensible life. Political power and theology were not the only ones to have taken up arms against it—just as they had in late antiquity against icons. Philosophy, too, has made of it a true pariah: It has decreed that the sensible has no existence separate or separable from the subject who knows the real through the mediation of the sensible. Sensible life is rigorously limited and reduced to an internal accident of psychism. It exists solely within the subject and never outside of it. Sensible life represents an inferior stage, which is private and incommunicable, of the authentic cognitive act that is consummated in the higher chambers of the understanding and the mind.

The refusal to acknowledge that the sensible has any ontological autonomy is more than one of the many founding myths that modernity has devised and cultivated: In the seemingly insignificant gesture with which René Descartes attempted to liberate the mind from “all those small images flitting through the air, which are called ‘intentional species,’ and which worry the imagination of the philosophers so much,” what was in fact played out was philosophy’s decisive battle against its own past.1 The crusade against an opinion that Hobbes would define as “worse than any paradox, as being a plain impossibility,” rallied almost every thinker that positioned himself under the flag of modernity.2 Unsurprisingly, each of them had to set out their own theory of truth, affirming that “it is unlikely that objects transmit images, or species, that resemble them,” as Malebranche puts it in The Search After Truth.3

The reasons for this unanimity are easy to understand. Only through the definition of what may seem to be a simple gnoseological detail does it become possible to think a subject truly autonomous from the world and from the surrounding objects. Only the exile of intentional species has made it possible for the subject to coincide with thought, as activity and as result, in all of its forms. With Descartes, sensation and sensitive life (exactly like thought and intellectual life) can be explained only if we take the subject as a point of departure; there is “no need to assume that something material passes from the objects to our eyes to make us see colors and light,” but neither there is need for “anything in these objects to be similar to the ideas or the sensations that we have of them.”4 The existence of man is sufficient in itself to explain the existence of sensation and its functioning:

just as nothing comes out from the bodies that a blind man senses which must be transmitted along the length of his stick into his hand, and as the resistance or the movement of these bodies, which is the sole cause of the sensations he has of them, is nothing like the ideas he forms of them.5

In the eyes of the moderns, the intentional species seemed like a useless obstacle preventing one from thinking subjective perception iuxta propria principia: The existence of the sensible, separated at once from subject and from object, makes it effectively impossible to reduce the theory of knowledge to psychology or to a theory of the subject. Every theory of the images thus becomes an accidental branch of anthropology. And conversely, it is only by removing these “images” from every spiritual act that one has been able to consider the self-reflection of the subject as the formal and the material foundation of all knowledge.

The truth and the coherence of the Cartesian trilemma are threatened by the existence of intentional species. An intention is a shard of objectuality that has pierced the subject, hindering it from transiting from the cogito to the sum res cogitans without an ontological leap. Vice versa, such an intention depicts the subject as projected toward the object and toward external reality of a nonpsychic character (literally tending toward it). If it is thanks to these species that we are able to feel and think, then each sensation and every act of thought will demonstrate not the truth of the subject or its nature, but nothing other than the existence of a space within which the subject and the object are confounded.

As absurd as it may appear to those who for centuries have been accustomed to considering it as nothing more than a primitive phantasmagoria of the way in which we come to know things, the doctrine of intentional species was inspired by “phenomenological” evidence....