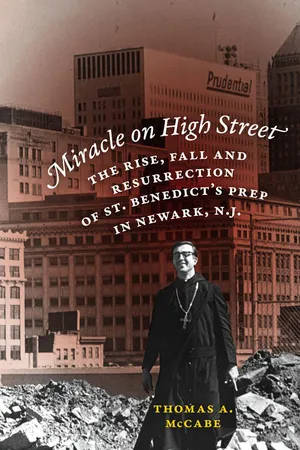

![]()

1 Newark’s Forgotten Riot

The miracle on High Street actually began on William Street.

On September 5, 1854, three thousand men, most of them wearing Prince Albert coats, round felt hats, and red sashes slung over their shoulders, paraded through the streets of Newark. Thirteen different lodges of the American Protestant Association, all marching behind their own banners and bands, wanted to make a show of force on behalf of the Know-Nothing Party before the November elections. Since 1850 the nativist political party had garnered swift support for its anti-Catholic and anti-foreigner platform. Nationwide the party now had over one million members and had put thousands in office, ranging from the grassroots level to the halls of Congress. That day, almost all the men carried swords and pistols. Marching four abreast, the “long and imposing” procession sang anti-Catholic ditties and shouted the party’s motto, “Americans must rule America.” They eventually stopped for lunch at Military Hall on Market Street, where they ate and drank for the next two hours.1

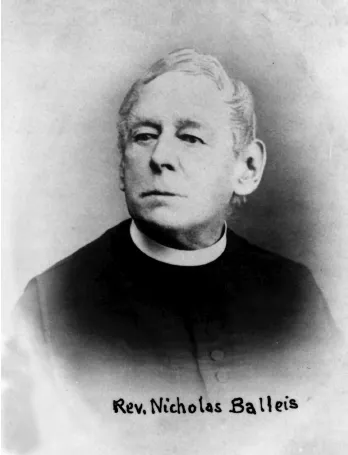

Just a few blocks away on William Street, Father Nicholas Balleis, a Benedictine missionary from Austria, dined with three other priests at his living quarters adjacent to St. Mary’s, a small wooden church built in 1842 to minister to the growing number of German Catholic immigrants in the neighborhood. Father Nicholas had read about the parade in the morning’s paper—the Newark Daily Advertiser noted, “Know-Nothingism is said to be spreading, not only in this city but in all the surrounding towns and villages”—but he did not make much of it until he heard music playing outside. Scheduled to march through a nearby native Protestant neighborhood, the parade’s course was changed after lunch, partly because of the unseasonably hot day, and as a result it staggered up William Street at three o’clock in the afternoon. As the various lodges ascended the hill, they shouted and sang and fired their pistols into the air. By the time the Henry Clay Lodge reached the tiny church, a sizeable crowd of men, women, and children gathered to witness the spectacle. In particular, men working in the Halsey and Taylor leather works, and other nearby factories, rushed out to see the parade. Across the street, students watched the scene unfold through the school windows. One student recalled, “The Orangemen discharged their firearms and hurled stones and other missiles at the white Cross on the apex of the Church, but they could not get it down.” In the tense moments that followed, men hurled insults and threats, and some threw more stones. The riot was on!2

Nativist marchers, fueled by their hatred of Catholics and also by hours of drinking, quickly broke ranks and brawled with the onrushing Catholic workingmen. Some rioters sidestepped the melee, fought their way into the church, and ransacked St. Mary’s, leaving the altar overturned, a statue of the Virgin Mary decapitated, and the organ pipes twisted and destroyed. A frightened Father Nicholas hid under his bed. His assistant, Father Charles Geyerstanger, displayed more courage and forced his way through the raiding party to retrieve the Blessed Sacrament. He took it to a neighboring home and quickly returned to sound the alarm. Sensing imminent danger, Fathers Nicholas and Charles shed their cassocks, fled the rectory, and disappeared into a parishioner’s home. Moments later several men broke into the rectory looking for the departed clergymen but found only an old German housekeeper. Pointing revolvers at her head, they demanded to know where the priests went. She replied, “Shoot! I am only a poor woman!” She then took her broom and brandished it in defiance.3

Outside there were repeated calls to torch the church, but the combination of crowd resistance, the arrival of police, the work of marshals to reform the procession, and the warnings of Father Charles, who had returned to the scene, prevented it. As word spread of the riot, thousands came to watch the unfolding violence; others hid, including a nun and her charges at a nearby Catholic orphanage, fearing the wrath of the marauding mob. At St. Mary’s, Father Nicholas gave last rites to Thomas McCarthy, an Irish Catholic tanner who had been gunned down by one of the marchers. Another man, Michael McDermott, a watchman at a trunk factory, would die several days later after being repeatedly stabbed in the back. Others, struck by stones, lay severely wounded. The police made only two arrests, and armed parishioners guarded the sacked church through the night. It was a “typical Know-Nothing riot,” argued one historian, as armed Protestants marched through a heavily Catholic area, incited local residents, reacted to the violence with force, and then claimed self-defense. The day after the riot, the Newark Daily Mercury, a mouthpiece for the Know-Nothing Party, blamed the victims, saying that eyewitnesses “impute the blame entirely to the Irish Catholics.”4

Father Nicholas Balleis was the first Benedictine in Newark, and while he ministered to the German Catholic community at St. Mary’s Church in the 1840s, he left the city in the wake of the 1854 Know-Nothing riot.

Talk of the riot dominated conversation in the city for days, and some newspapers eventually retracted their accusations in reaction to pressure from Newark’s bishop, James Roosevelt Bayley. While Bayley excoriated the press for placing the blame on Catholics, priests sought to quell their seething coreligionists. Although some wanted revenge, Fathers Bernard McQuaid, the future president of Seton Hall College, and Patrick Moran, the pastor at nearby St. Patrick’s, preached calm in the days and weeks after the attack. The historian Joseph Flynn commented on the riot’s aftermath, writing, “The tempest passed, and, while its trail was long visible, still it bore fruit.” Newark’s forgotten riot on William Street led to at least one fortunate event: the unlikely but ultimately fruitful arrival of the Benedictines to the city, which they announced by overseeing the completion of a new church. Made of brick and mortar and almost three times the size of the tiny wooden edifice it replaced, the new St. Mary’s now faced High Street.5

City upon a Hill

In 1857, as the Benedictines settled just outside Newark’s downtown, they set out to build a new “city upon a hill.” Newark’s first European settlers had pledged to do the same nearly two hundred years earlier, in May 1666, when Puritans from the New Haven founded the last theocracy in the American colonies on the banks of the Passaic River. Lauded as a “Terrestrial Canaan … where the Land floweth with milk and honey,” the small, isolated town revolved around farming and “godly government” for the better part of a century, and its inhabitants were described as “remarkably plain, simple, sober, praying, orderly, and religious people.” But Newark could not remain an exclusive religious outpost forever, and after a period of road and bridge building in the 1790s and canal and railroad construction in the 1830s, the once quiet and tranquil community transformed itself into a hub of industry, invention, and immigration.6

While many native Newarkers welcomed industrialization, they did not always welcome immigrants. The Irish began arriving in the 1820s—men dug the Morris Canal, laid railroads, or worked in a variety of small factories, while women most often labored as domestics—but immigration reached epic proportions in the wake of the Irish Potato Famine beginning in 1845. Pushed out of Ireland by starvation and disease, the Irish crowded into a handful of distinct neighborhoods throughout the city. The largest concentration was in “Down Neck,” a swampy, malaria-infested section that provided cheap rents and “a comfortable distance from unfriendly Protestant areas of town.” The sons and daughters of Erin had a difficult time adjusting to life in Newark; rural, poor, and Catholic, they struggled to make their way in an urban, industrial, and Protestant society. Depicted as stupid, lazy, drunk, and aggressive, the Irish in Newark were often the object of ridicule and derision. Protestant ruffians hurled insults during the city’s inaugural St. Patrick’s Day parade in 1834, routinely hanged “St. Paddy” in effigy during the 1840s, and disturbed the procession of James Roosevelt Bayley’s installation as bishop in 1853.7

In the late 1840s, German immigrants, many of them refugees of the failed revolutions of 1848, joined the Irish in Newark, settling in the “Hill District” around St. Mary’s Church. There they recreated important elements of the fatherland, including beer gardens, song festivals, and Turner societies, and often worked in neighborhood industries as shoemakers, trunk makers, brewers, and jewelry manufacturers. While Germans were generally more literate and skilled than the Irish, they too faced prejudice, in particular for playing sports, drinking beer, and singing songs on Sunday afternoons. The Irish and German immigrant influx into the city caused Newark’s total population to skyrocket from seven thousand in 1820 to more than one hundred thousand in 1870, more than a tenfold increase. By 1860, one-third of Newark’s population was foreign-born. White Anglo-Saxon Protestants often felt that Newark was a city under siege.8

Despite industrial progress and the promise of even more to come, urban life in the antebellum United States was in turmoil. People questioned traditional notions of authority, violence was commonplace, social tensions multiplied, and the economy fluctuated between the extremes of boom and bust. Many native-born Americans often blamed a growing list of social, economic, and political problems on recently arrived immigrants. By 1850, Newark was the “nation’s unhealthiest city” as it suffered from a variety of public health crises, including epidemics, poor sanitation, inadequate water supply, and massive pollution. Higher than normal rates of poverty, alcoholism, and criminality among the Irish increased hostility toward them further still. One in three German immigrants were Catholic, and they were not without enemies either, since they insisted on preserving their language and culture in a strange land. Whether in Newark, Boston, Philadelphia, or New York, native-born Protestants viewed Catholics as foreign, mysterious, and increasingly dangerous to their way of life, and as a result, hostile mobs often threatened to burn churches, rectories, and convents, and to physically harm priests, nuns, and other defenders of the faith.9

In Newark, tension between natives and immigrants came to a boil over the schools. Catholic clergy questioned the validity of the public school system by asking if Protestant prayers and devotional practices were acceptable in a publicly financed institution. They argued that mandatory use of the King James Bible or certain textbooks that incorporated a detectable anti-Catholic bias seemed to sanction a state religion, and flew in the face of religious tolerance. Bishop Bayley worried about the influence of the public schools, arguing, “The Protestants make the greatest efforts to pervert our youth, mainly in establishing free schools, supported by the state.” Catholic clergy demanded that local government support parochial schools as well, but determined Protestant opposition precluded any financial help, especially since the fledgling public school system needed all the resources it could get. But lack of public support for parochial schools did not deter Bayley from issuing a statewide rallying cry for a parallel system shortly after he was installed as the first bishop of Newark. In 1853 he wanted to see “every Catholic child in the State in a Catholic school.” When the bishop called on the Benedictines in the weeks after the Know-Nothing attack on St. Mary’s Church, he knew all too well that they were also world-class educators.10

Stability and Adaptability

A week after the riot Father Boniface Wimmer, the founder of the Order of St. Benedict (OSB) in the United States, traveled from Latrobe, Pennsylvania, to Newark in order to console and advise a visibly shaken Father Nicholas Balleis. Wimmer was well aware of the threat of nativists in his own state, observing, “Our newest political sect, the Know Nothings, would like to eat us, skin and hair, but it does not go so easily. The pressure on them is as it was on the Egyptians; they see us grow but they cannot stop us.” An emboldened Wimmer thought that more property should be acquired so a bigger church could be built. Traumatized by the riot and embroiled in a string of controversies with his parishioners, though, Father Nicholas quickly transferred church property to Bishop Bayley and left for another assignment. In turn, the bishop redoubled his efforts to bring Benedictines to Newark and offered the parish to Wimmer, telling him, “I am most anxious to have your Order established here.” It was part of his strategy to fortify a Catholic community under attack.11

Nicknamed the “Project Maker,” Father Boniface led the active, aggressive lifestyle of a missionary. Upon his arrival in southwestern Pennsylvania in 1846, for example, he wielded an axe as he and his fellow Benedictines quickly got to work felling trees, clearing fields, and constructing the new monastery’s first buildings. Quick-tempered but tolerant, he had a grand vision of what his Order could accomplish in the United States. A year before founding the first American Benedictine monastery, he wrote, “Benedictines are men of stability; they are not wandering monks; they acquire lands and bring them under cultivation and become thoroughly affiliated to the country and people to which they belong.” Moreover, based on more than a millennium of experience, the Benedictine Order could “very readily adapt itself to all times and circumstances.” Benedictines took three vows: conversion of life, obedience, and stability of place. The vow of stability, unique among religious orders, anchored them in a specific location. As a result it was inevitable that a particular monastery would become “thoroughly affiliated to the country and people to which they belong.” The interplay of these two essential elements—stability and adaptability—proved to be among the greatest assets of Benedictine monastic life in the United States.12

Father Boniface preferred mission work in farm country to that in teeming cities, yet only a year or so after settling in rural Pennsylvania he started receiving letters from Newark. Father Nicholas first wrote in 1847, asking him to send priests to minister to the city’s growing German Catholic population. One monk arrived the following year, but stayed for only six months, and it would be another four years before Father Charles, who heroically saved the Holy Eucharist during the attack on St. Mary’s, came to the city. During the 1850s, when Father Boniface looked to start other monasteries, he looked only westward, preferring to follow the flood of German immigrants across the Midwest. Even before the riot, he had a lukewarm attitude toward St. Mary’s in Newark, confessing to his superior in Germany, “It is true, the parish has a fine location, the city can easily be reached, but I am afraid of cities.” After the riot, he wrote Bayley, “Why should we rush into cities to draw upon us the wrath and hatred of others?”13

Bayley ignored Wimmer’s rebuff and asked again. This time, the German monk elaborated on his reluctance to come to the city, saying, “In the country, far from the noise of the cities, we lead a happy life, and if we are not doing first rate we are doing at least well …. How would we do in a city, I do not know.” Wimmer feared that monastic observance might suffer in an urban setting, as he pondered whether “we might lose the simplicity of manner, the poverty in our diet, the spirit of self-denial and the pure intention of our efforts.” His own experience raised “great doubts as to whether it would be good or evil for the Order to settle in cities.” Over the course of their three-year correspondence, Father Boniface indicated his preference for founding new monasteries in the West, which continued to flummox the eastern bishop. Bayley wrote Wimmer in 1857, “I cannot understand what East or West has to do with the matter when the question is the salvation of souls.” An exasperated Bayley did not yield, and pressed the matter further, writing, “Newark is so near to New York, as to be a suburb of that city. The German Catholic Population here is already large, and is increasing. It would give you a great center of influence,” and “I am certain...