![]()

CHAPTER 1

Due Rose, Due Volte

A STUDY OF EARLY MODERN SUBJECTIVITIES

Susan McClary

Modernism comes in many guises. In the early twenty-first century, we are most likely to associate the word with the recent postmodernist turn, with cultural upheavals a hundred years ago, or with the radical questioning of Enlightenment values entailed in the emergence of Romanticism. Pushing the term even further back, many humanities disciplines now refer to the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries as the “early modern” period. In musicology, however, the widespread use of period terms such as “Renaissance” and “Baroque” (themselves problematically borrowed from other disciplines and applied somewhat arbitrarily to music) has made it difficult to perceive the “modernity” in earlier repertories. The fact that we have no agreed-upon way of analyzing music from before the eighteenth century causes anything prior to Bach still to appear primitive—anything other than “modern.”

The other chapters in this volume quite appropriately focus on later modernist crises, for these are the periods for which Lawrence Kramer has established himself as a leading authority. In his pathbreaking series of books and articles, Kramer has taken the standard classical repertories of the late eighteenth and the nineteenth centuries—long since elevated to the untouchable sphere of “absolute” music—and demonstrated the ways those privileged compositions produce meaning. Allegations to the contrary, he has never sought to undermine the aesthetic worth of classic masterpieces;1 he simply has wanted to add cultural theory and interpretation to the mix. Rather than the smooth, polished, ineffable entities celebrated by generations of connoisseurs, Kramer offers us documents testifying to ever-changing cultural values, including reactions to the traumas of modernity. Because of his work, the music of Schubert, Schumann, Ives, and many others has acquired renewed meanings—controversial meanings, to be sure, but far more precious for being seen to engage with the messy enterprise of human experience at various moments in history.

Much of my work has addressed the same repertories on which Kramer concentrates his efforts, though I arrived at nineteenth-century studies from the opposite direction. I began my musicological career as a specialist of seventeenth-century music but quickly found that attempts at publishing my analyses and interpretations ran up against the commonly held belief that early music “does not work.” Frustrated by this bizarre but apparently nonnegotiable barrier, I decided that I needed to demonstrate the historical and ideological contingency of “absolute” music in order to deal seriously with the cultural values registered by earlier repertories, which in my view ought not to have required such elaborate special pleading. Thirty years after I started, I find it possible at last to address sixteenth-and seventeenth-century musics with the kind of analytical depth and the sorts of questions that Kramer brings to Mozart or Strauss.

My essay concerns two sixteenth-century settings of Francesco Petrarch’s Sonnet No. 245, “Due rose fresche.” Several sixteenth-century composers set this sonnet to music, most notably Andrea Gabrieli in 1566 and Luca Marenzio in 1585. Musicologists and performers regard both these settings as central to the madrigal repertory. As it turns out, Marenzio alludes throughout his version to Gabrieli’s in a gesture of homage and intertextual one-upmanship typical of court-based culture of the time. Marenzio could count on his performers’ and listeners’ familiarity with the former setting and thereby produce his own reading of both Petrarch’s sonnet and Gabrieli’s earlier reading of the same sonnet.

The mere nineteen years that separate Gabrieli’s setting from Marenzio’s proves crucial to their understandings not only of this poem but also of inherited traditions of music composition. Put simply, Marenzio resided on the modernist side of a cultural cataclysm that still resonates even today. Thus, although both composers ostensibly faced only the task of setting a given text, their very divergent assumptions and ideological priorities mark their responses, resulting in two significantly different interpretations of Petrarch’s sonnet.

Due rose fresche et colte in paradiso

1’altr’ier, nascendo il dì primo di maggio,

bel dono et d’un amante antique et saggio

tra duo minor egualmente diviso,

con sì dolce parlar et con un riso

da far innamorare un uom selvaggio,

di sfavillante et amoroso raggio

et Pun’ et 1’altro fe’ cangiare il viso.

“Non vede un simil par d’amanti il sole,”

dicea ridendo et sospirando inseme,

et stringendo ambedue volgeasi a torno.

Così partia le rose et le parole,

onde ’1 cor lasso ancor s’allegra et teme:

o felice eloquenzia! o lieto giorno!

Two roses, fresh and gathered in paradise the

other day when the first day of May was born,

a lovely gift by a lover old and wise

between two younger ones equally divided,

with words and a smile sweet enough

to cause a wild man to fall in love,

made a sparkling, amorous ray

change the faces of bodh.

“The sun does not see a similar pair of

lovers,” he said, bodh smiling and sighing,

and embracing both, he turned around.

Thus he divided the roses and his words;

and my weary heart still is glad and fearful:

O felicitous eloquence! O happy day!2

Written most likely in Avignon shortly before Petrarch learned of the death of the woman he called Laura (whom he idealized and loved from afar but never met), “Due rose fresche” imagines a celestial benediction of the poet and his beloved. A smiling, benign elder presides, offering the two young lovers the first roses of Maytime along with his blessing. Endingas it does with the peroration “O felicitous eloquence! O happy day,” the sonnet presents Petrarch at his most optimistic: no misogyny or what Nancy Vickers theorizes as dismembered body parts are in evidence here, only sweetness and light.3 In fact, musical settings of this sonnet seem to have been performed frequently at weddings in the sixteenth century.4

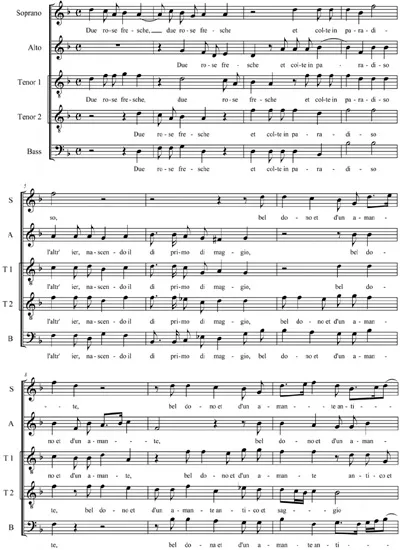

As one might anticipate, word paintings abound in both madrigal settings: their scores present two paired voices alone at “Due rose” and they burst into simulated laughter at “riso” and “ridendo.” In short, both pieces indulge in what my discipline deprecates as “madrigalisms.” I do not apologize for these figures; there they are in all their glory—though I would remind you that J. S. Bach never encountered an excuse for word painting that he could resist. The problem comes when we assume that the identification of word paintings exhausts the arsenal of critical tools that we can bring to bear on the madrigal repertory. Musicologists have long delighted in pointing out these Mickey Mouse depictions, allowing for a kind of positivistic hermeneutics, and they typically restrict commentary to that level.

Recall, however, that Gabrieli and Marenzio wrote their madrigals a good two centuries after Petrarch had established himself as one of the most insightful theorists of interiority in all Western history.5 Only if we accept that composers lag woefully behind the cultural agendas of other artists should we content ourselves with pointing at isolated figures and relating them literally to images in the poetry. We do not deal critically with the paintings of, say, Caravaggio by demonstrating that we can identify a represented horse or dog on the canvas, and we should not tolerate this egregiously low standard when we deal with music, either—not even that of early repertories.6

Consequently, as I discuss the two settings of “Due rose fresche,” I focus my attention on the ways in which the narrator’s subjectivity makes itself felt in each setting through moments of affective emphasis, repetitions, changes in the rate of activity, distortions, prolongations, or abrupt shifts. Although the poetic text always informs compositional strategies, such rhetorical choices do not reside at the level of individual words or even clusters of words. Indeed, each composer imposes his own interpretation on Petrarch’s sonnet, sometimes causing the text to speak meanings not necessarily evident in the poetry itself. Both, in other words, are already ventriloquizing Petrarch. And in the absence of a pure source, we may as well plunge in ourselves.

Andrea Gabrieli published his setting of “Due rose” in his Primo libro a cinque in 1566. As Alfred Einstein explains, Gabrieli was drawn at the time particularly to the fashionable idiom of pastoral poetry, and he infused much of his music with the buoyancy and joy characteristic of that genre. “Even when he turns to literary texts, to Petrarch, for example, as he does five times in his first book and once in his second, Gabrieli does not aspire to a more elevated style. For him Petrarch’s sonnet Due rose fresche is simply a wedding madrigal which he transforms into a masterpiece of easy grace.”7

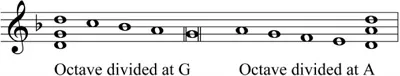

The madrigal operates entirely within G Hypodorian, which offers B

and D as well as G as regular points of cadential emphasis. Nothing in the piece challenges these modal limits, nor does Gabrieli rebel against the structure of Petrarch’s sonnet: each poetic caesura receives a corresponding cadence. Occasionally Gabrieli repeats a phrase for the sake of rhetorical emphasis or as part of a point of imitation—that is, for purposes of

textural (rather than

textual) elaboration. But he accepts Petrarch’s verse quite unproblematically with respect to form and also, as we shall see, with respect to content.

As an opening gambit, however, Gabrieli at least toys with the ambiguity most typical of G Hypodorian. The modal octave stretching from D to D has G as its final, but it has a strong tendency to imply an alternative division of the octave at A, with D as the implicit final (

Example 1.1). The principal motive in the first three measures traces a powerful descent through the diapente (the interval of a fifth) from D toward G, but it halts each time unfinished at A (soprano, mm. 1-2; tenor I, mm. 2-3; tenor 2, m. 2). Moreover, by withholding all leading tones, the countermotive refuses to decide between G and D orientations, repeatedly stressing an equivocal F

instead.

Many a madrigalist would have used such an opening to plant an internal contradiction that would drive the rest of the composition. But Gabrieli seems to have other priorities. After this passage of delicious, indeterminate hovering, he pivots through the D-minor triad that could have threatened modal integrity to a blossoming B

sonority on “paradiso.” Not only do we shift from minor to major, but the voices all suddenly lift from their earthbound tessitura to a momentarily sustained glimpse of heavenly heights. Returning us quickly to Petrarch’s text, Gabrieli

solves the ambiguity of the first line in measure 6 with a cadence confirming G as the final and “maggio” as the end of the first couplet (

Example 1.2, mm. 1-6).

EXAMPLE 1.1. G-Hypodorian species and division at D.

Given the radical experiments produced by Gabrieli’s contemporaries, this profoundly diatonic beginning—and, indeed, this entire madrigal—might seem conservative or timid. But Gabrieli’s agenda here involves the production of rhetorical effects within a secure affective universe. The “easy grace” of which Einstein writes reveals itself in the luxuriant unfurling (like rose petals) of the ambiguous opening point of imitation, the breathless and unexpected simulation of paradise itself, and the deft return to discursive reality for the cadence—quite a bit to accomplish within about seventeen seconds of sound. With expressive mastery such as this, Gabrieli apparently felt no need to go beyond conventional strictures. Instead, he makes the attainment of bliss seem always within our grasp—and within the grasp of the couple at whose wedding such a piece might have provided a musical backdrop.

EXAMPLE 1.2. Andrea Gabrieli, “Due rose fresche,” mm. 1—13.

Gabrieli chooses to begin his setting of Petrarch’s second couplet with a melodic motive that recalls the first, though now with a harmonization affiliated with B

(

Example 1.2, mm. 6ff.) Formerly aligned with “paradiso,” this sonority now unfolds as a carefree pastoral landscape in which the imitative voices play an erotically tinged form of tag. The game comes to a temporary halt with a direct descent through the G diapente to a half cadence—still incomplete, as in the opening statements of this motive, but now made functionally clear by the F# that points unequivocally to G (m. 6).

For the remainder of the two-part madrigal,...