![]()

CHAPTER 1

Naming Subjects: “Paraphilias”

You who read me—are you certain you understand my language?

—JORGE LUIS BORGES, “The Library of Babel”

The first and most important rule is not to believe the statement that the patient was attracted to the same sex since childhood.

—WILHELM STEKEL, “Is Homosexuality Curable?”

The catalog record for Epistemology of the Closet demonstrates the performativity of subject headings—the authorized terms by which we search for books. I ask you to reassume the position of a cataloger in 1990, and think now of a handful of key words and phrases that represent what Epistemology of the Closet is about. Bear in mind that, as a cataloger, you consider what your library patrons would be most likely to seek in the catalog if they were looking for books on the subjects you assign. Subject searches are performed as a gathering technique when readers do not know the titles and authors of the texts but have an idea of the topic they are looking for. If you were properly cataloging this book according to the rules, you would look to the Library of Congress Subject Headings to find the authorized forms of the terms. In 1990 the lists of headings would have been sitting on your desk in a massive five-volume set clothed in red covers. A significant amount of training is required, as is a solid grasp of the subject matter, to be able to apply the headings, add subdivisions, and encode it all adequately. For this text, catalogers chose to provide the major authors addressed by Sedgwick as subjects, as well as four topical subject headings. Recall again that the term “queer theory” had been coined just months before the publication of the book, and it was not officially authorized as a subject heading by the Library of Congress until 2006. I leave this exercise off here and leave it to you to compare your own assessment of what Epistemology of the Closet is about (an impossibly absurd task, I realize) with what the Library of Congress chose for the 1990 edition. Next we move to the subject of “Paraphilias,” formerly called “Sexual perversion.”

Melville, Herman, 1819–1891. Billy Budd.

James, Henry, 1843–1916—Criticism and interpretation.

Wilde, Oscar, 1854–1900—Criticism and interpretation.

Proust, Marcel, 1871–1922. A la recherché du temps perdu.

Nietzsche, Friedrich Wilhelm, 1844–1900.

American fiction—Men authors—History and criticism.

Homosexuality and literature.

Gays’ writings—History and criticism—Theory, etc.

Gay men in literature.1

The inspiration for this book arose out of my own struggles as a seeker of historical materials on homosexuality and bisexuality via the University of Wisconsin library catalog in 2009—as a disciplined subject, so to speak. I performed a keyword search to locate catalog records that included the term “homosexual” anywhere. Upon finding some entries of interest, I clicked on links to various author names and subject headings, and eventually my wanderings conveyed me to the record for the 1934 edition of Wilhelm Stekel’s Bi-Sexual Love: The Homosexual Neurosis, which brought my browsing to a halt. I noticed that the record contained no headings for bisexuality or homosexuality. Rather, the only two subject headings assigned to this book were “Neuroses” and “Paraphilias.” As the latter term was unfamiliar to me at the time, my first inclination was to think that it must have been a mistake—perhaps a medical heading, or a relic that somehow never got updated. I then clicked on the heading to see if it was applied to other works in the catalog and discovered that it was included in over three hundred bibliographic records.

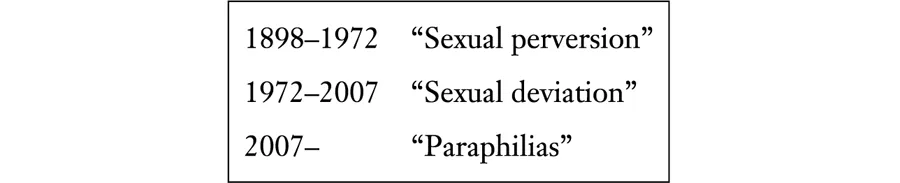

Perplexed, I searched the Library of Congress’s catalog and WorldCat (a shared catalog across 72,000 libraries) and found that it was clearly a currently authorized subject heading.2 I consulted the authority record for the heading in the Library of Congress authorities database, which indicated that “Paraphilias” was authorized in 2007 to replace “Sexual deviation” (see Figure 3). The record also revealed that the reasons for preferring this term were supplied by psychiatric literature. The 1934 Stekel book was assigned this heading because of the technological application called “global” or “batch updating,” which allows a librarian to update automatically all catalog records that contain a given heading to the current form. Stekel’s book, then, which had originally been assigned the headings “Sexual perversion” and “Neuroses,” is now cataloged with “Paraphilias” and “Neuroses,” providing no heading for homosexuality, bisexuality, or any reference to this as a historical text.3 With the global update technology, “Paraphilias” replaced “Sexual deviation” in most catalogs, including that of the Library of Congress, without any human review of the catalog records. This means that, by virtue of automation, texts that were cataloged in the early part of the twentieth century retain formerly held attitudes that associated homosexuality and bisexuality with perversion, but now in anachronistic terms.4

While the story of my search is only one personal anecdote, I hope that it resonates with readers and illustrates a sense of being disciplined, which manifested in the jarring experience of struggling to understand my own identifications in unintelligible terms. It demonstrates how the disciplinary apparatus affects both the text and the reader. The classificatory mechanism inscribes a book’s subject in the catalog in a language that may be foreign to both the text and the person seeking the text, resulting in a range of effects and affects. I can also draw from other encounters: For example, when I deliver talks on this topic, I often begin by asking my audience if they’ve ever heard this term. Hands very rarely go up, and while this may have something to do with a risk of exposure, shyness, or disinterest, the regularity with which I face blank stares upon asking this question is notable. In conversation people generally require an explanation if I mention my research on paraphilias. And in my own personal interactions with popular culture, the only time I recall hearing the term is in an episode of Law and Order: Special Victims Unit. These encounters lead me to surmise that this is a term that simply doesn’t carry meaning for the vast majority of people and is used only in certain circles, like law and medicine. Furthermore, and more important for the purpose of this study, what these experiences demonstrate is the contrast between the language of people on the street, of humanities and social science scholars, and of psychiatric professionals and scholars. The consequences of the authorization and use of “paraphilias” are many, including the erasure of a whole range of materials, the misrepresentation of historical conceptions of perversion, and the silencing of voices outside of the medical sciences. Placing the term “paraphilias” at the heart of this chapter illustrates how a single Library of Congress Subject Heading serves to discipline sex and sexualities through the act of naming.

Figure 3. Library of Congress subject headings, by period of authorization.

This chapter sets out to perform a history of the present practice of categorizing books on perversion with the heading “Paraphilias” and to seek an understanding of how this medicalized term has taken hold in the library catalog. The Library of Congress is in dialogue with and reinforces psychiatric norms in a conversation that silences would-be interlocutors, particularly from the humanities and the street. But perhaps more significantly, the history of these terms in knowledge organization practice provides a glimpse of how the Library of Congress participated in the development and refinement of categories alongside other federal bureaucracies that were trying to gain a conceptual mastery over perversion in order to define both desirable characteristics for citizenship and the deviations by which to exclude people from membership.

Subject Heading Practices and Procedures

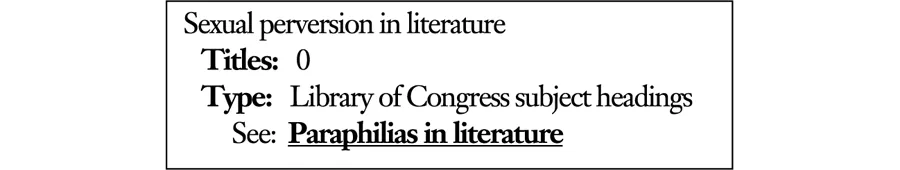

The Library of Congress Subject Heading (LCSH) authorities database contains a half-million subject authority records, which designate the terms that can be used to catalog works by subject and how these terms are structured in library catalogs. LCSH is a syndetic system, meaning that it connects related terms, synonyms, or variants by using cross-references in a database within the catalog. Online library catalogs often provide links to “Use” or “See” references, so that patrons are directed to the authorized terms for their searches, charting the correct course that will lead readers to their books. For those who search a catalog by subject using a nonpreferred term—“Sexual perversion in literature,” for instance—the authority mechanism will redirect the seeker to the correct term—in this case it will say “See: Paraphilias in literature.” Not only is LCSH a controlled vocabulary, but the terms are authorized by a governing body that determines which terms are valid and the processes by which they become authority headings; in this case it is a committee composed of cataloging staff at the Library of Congress. The potential for reach of the vocabulary has been expanded with the recent creation of the Library of Congress Linked Data Service, which “enables both humans and machines to programmatically access authority data at the Library of Congress.”5 LCSH and other vocabularies are part of the public domain and terms are accessible through uniform resource indicators (URIs).

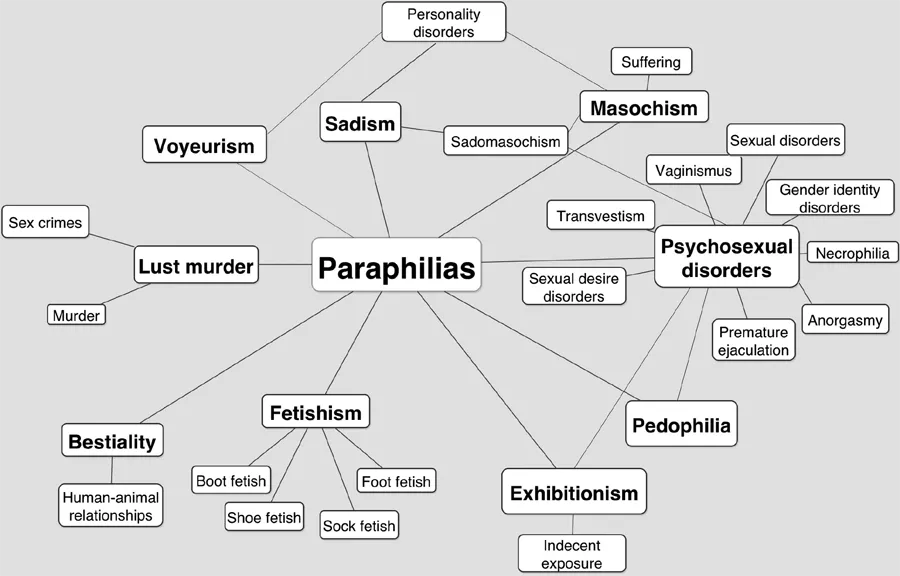

The database also helps people find terms that are related to the topic of interest. They may be broader or narrower terms in a hierarchy, as with “Baby bonnets,” which is a member of “Hats,” or they might be topically associated, as “Baby bonnets” is related to “Infants’ clothing.” Figure 4 provides a map of the social network of terms most closely related to “Paraphilias.” Most are narrower terms: “Sadism,” “Masochism,” “Voyeurism,” “Lust murder,” “Bestiality,” “Fetishism,” “Exhibitionism,” and “Pedophilia.” One term is provided in the authority record as a “See also” term (meaning that related items might be found with another heading): “Psychosexual disorders.”6 The illustration also shows all of the narrower and related terms for that level, connecting terms that are considered related. One could easily carry this exercise on, extending related terms nearly endlessly, playing a game of “six degrees of paraphilias.”

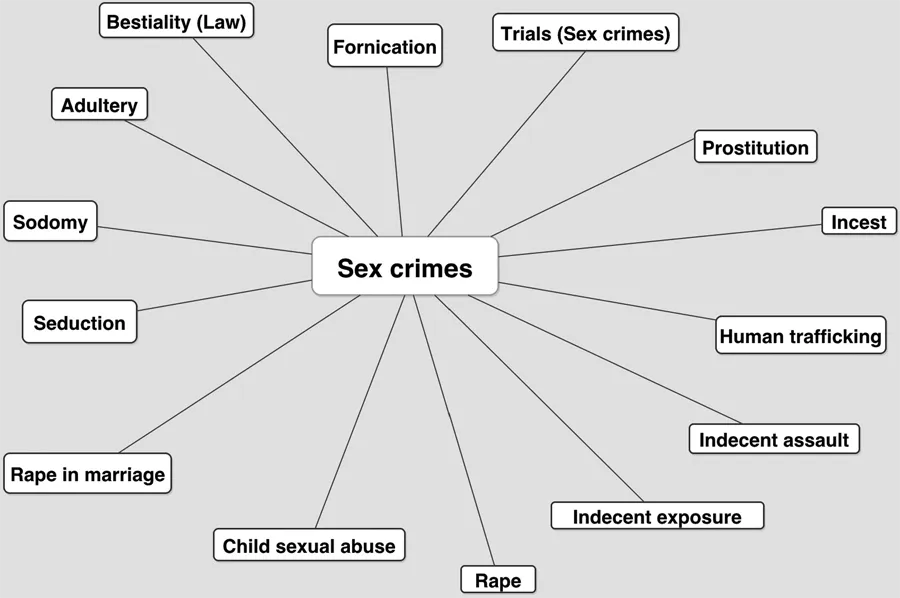

One is likely to be struck by the presences, absences, and relationships produced by the network of authority records. Why, connected to “Fetish,” are there only the types “Foot,” “Boot,” “Sock,” and “Shoe”? Have books only been written on these fetishes, and why does it get so specific with regard to the extensions of the foot? The category “Psychosexual disorders” is a bizarrely exclusive collection of terms—that “Transvestism” is in this grouping is troubling, especially when displayed in relation to the other terms in this family of “disorders.” “Paraphilias” is two degrees from both “Sex crimes” and “Murder” via “Lust murder.” If we extend a map of “Sex crimes,” we see that the “Paraphilias” are not far removed from all sorts of criminal acts, and we see some disturbing notions of what counts as a sex crime (Figure 5).7

Figure 4. Terms related to “Paraphilias.”

Figure 5. Terms related to “Sex crimes.”

Aside from the medical and criminal associations, there is the concern about the terminology chosen for the concept. One of the Library of Congress’s principles states that it will create a new heading when it appears in the literature, but it also has a policy to authorize terms in general use, rather than jargon.8 The American Library Association and the Library of Congress endorsed a statement issued in 1975 stating:

The authentic name of ethnic, national, religious, social, or sexual groups should be established if such a name is determinable. If a group does not have an authentic name, the name preferred by the group should be established. The determination of the authentic or preferred name should be based upon the literature of the people themselves (not upon outside sources or experts), upon organizational self-identification, and/or upon group member experts.9

Although “paraphilias” does not name a group or an identity category, it could be argued that the term refers to people and their sexual practices; it is a diagnostic category, and it would seem that such a diagnosis may carry the assumption that a person has a disorder or is disordered. The medicalization of a set of behaviors should not so readily be taken as given, however, and I would suggest that those who engage in, carry an identification with, or are curious about any of the practices that fall within this category should be considered in decisions regarding what they are called. In using medical jargon, the Library of Congress effectively marginalizes not only a set of practices but also those who engage in any of the acts or seek information about them. As Sedgwick so elegantly states:

To alienate conclusively, definitionally, from anyone on any theoretical ground the authority to describe and name their own sexual desire is a terribly consequential seizure. In [the twentieth] century, in which sexuality has been made expressive of the essence of both identity and knowledge, it may represent the most intimate violence possible. It is also an act replete with the most disempowering mundane institutional effects and potentials.10

In 2016, over 650 books in the Library of Congress collection are cataloged with the subject heading “Paraphilias” or with ...