![]()

Part I: Monuments, Imitation, and the Noble Ideal in Early Renaissance Italy

![]()

Introduction. Reinventing Nobility? Artifacts and the Monumental Pose from Petrarch to Platina

The Florentine church of San Lorenzo is famous for Michelangelo’s Medici chapel (1519–34), whose main point of interest is the elaborate tomb monuments to Giuliano and Lorenzo. Each year, thousands of tourists visit the site to pay their respects to Michelangelo and gaze at the large statues of two good-looking young princes. Many visitors do not notice the masks displayed prominently on the men’s armor, next to the statue of Night, and in the decorative frieze around the room; and most visitors are unaware that the statues were not designed to depict either man with any kind of visual accuracy. Michelangelo is reputed to have said—apparently with great prescience—“in a thousand years, nobody will know that they looked any different.”1

Although statues like these were seen as exalting the person commemorated, it has frequently been observed that in the early Renaissance, images of people were considered not so much imitations of reality as a part of “reality” itself.2 The separation of this kind of representation from “real” reality is part of the story of this book, as this separation occurred alongside and contributed to a rhetorical stance that I call the monumental pose—a pose that demanded and authorized an outward projection of authority, which might or might not coincide with some inner sentiment. The Medici tombs are useful in opening this discussion, as tourists gaze not on true-to-life funerary portraits, but rather on what Stephen Campbell has called “ideal heroic bodies.” These ideal figures are linked with a series of prominently placed masks or larvae, a word that could also translate as “phantasms” or “ghosts.”3 The conventions of tomb sculpture required an idealized effigy of the young princes; Michelangelo, in taking this demand one step further and adding masks that suggest hollowness while emphasizing the artifice involved in crafting these ideal bodies, opened up a gap—much discussed by his contemporaries—between the visual evidence (the tomb sculptures) and the original point of reference (the actual physiognomy of two young men). Although facial features are clearly sculpted, and although (or perhaps because) clothing is so closely molded to the body that it is difficult to distinguish clothing from skin, there are no inscriptions anywhere and the monument is thus self-consciously a simulacrum, a self-referential hollow surface that is more a celebration of art than of the young men themselves.4

Although Michelangelo’s point may have been (as Campbell has argued) a valorization of artifice and surface, of the “undivinity” of art in general and of his own art in particular, the idealized heroic bodies and the ironic mask-like nature of the entire monumentalizing program reflect a far broader and growing sense of contradiction between the will to self-monumentalize (on the part of the elite), and the need to create an enduring, monumentalizing image that was unique but flexible enough to adapt to changing circumstances. The Medici tombs—with their lack of inscribed dates and names, and their idealizing, nonmimetic statues—exemplify these competing demands.5 Given the tombs’ emphasis on beautiful surface rather than specific historical referent, they also illustrate tensions between the interests of those who commission monuments, and those who make them—who likewise want to “self-monumentalize.”

In order to situate the Medici tombs in some kind of context, we should go back in time to consider this need to “self-monumentalize.” Dante was famously preoccupied with the problem of how a man eternalizes himself (“come l’uom s’etterna”; Inferno 15.85)—an issue that imposed conflicting pressures on men of letters, artists, and their patrons in early modern Italy. On the one hand, a successful literary man was expected to maximize his social and political status and to follow the example of active virile writers like Cicero. Learning from his reading, he was to perform and to write, to make himself into a monument by creating an outward identity for himself and rendering himself part of a permanent cultural patrimony. On the other hand, precisely because social status was changing, and the place of the literary man was not secure at the emerging Italian courts, men were forced to adapt to changing circumstances. Following the example of historical figures became problematic, as a new awareness of the passage of history and a sense of inevitable distance from the past contributed to a gradual move away from the use of great exemplars in humanist teaching.6 As we shall see, early modern Italian writers tended to conceive of personal and familial glory in a particularly concrete way—a perception at variance with the new imperative to mold oneself to changing circumstances. The quest for an eternity guaranteed by monumentality generated what I call the “monumental pose”: the self-conscious projection of an image derived from the ideal of visually comprehensible and reproducible exemplars. Since this ideal, however, revealed an “interior” to the subject that was seen as suspect, effeminizing, or both, it needed to be recast as monumental and masculine.

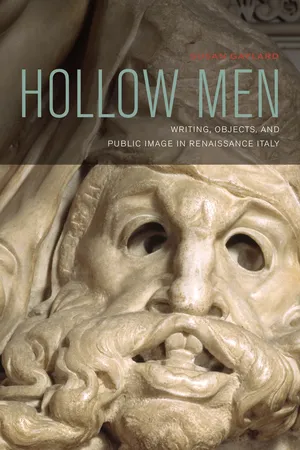

In the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, the contradictory requirements to be both monumental and flexible frequently opened up a gap between exterior “surface” and interior “character”—a gap instantiated (intentionally or not) in the Medici chapel masks. The question of “interior” and “exterior” has been usefully examined by John Martin, who shows that the tension between the emerging sixteenth-century concept of sincerity and the changing idea of prudence (newly divorced from ethics) resulted in a more complex sense of the “individual,” also called the “modern subject.”7 The new attention given to a person’s “interior” as distinct from his or her external behavior is also related to the failure of exemplarity theories: According to the humanists, a man should emulate ancient examples so as to become an exemplar himself for future generations. Yet this paradigm ultimately failed, resulting in what François Rigolot has called a “retreat into self-absorbed interiority” by the end of the sixteenth century.8 In both approaches, there is a clear relationship between the emerging subject and the notion of identity as a performance.9 The Medici tombs, with their suggestion of hollow surfaces, and their emphasis on the mask, offer an interesting gloss on William Egginton’s relating the emergence of subjectivity to sixteenth-century developments in theater: Early in the century, the tombs suggest a theatrical split between interior and exterior.10 Indeed, the Medici monuments showcase the issue with the mask beneath Night’s shoulder, which is uncannily inhabited by wide staring eyes, visible only from certain viewpoints (see the cover image of this book).11 My project follows this line of thought beyond the visual arts into literature, to show that the emerging problematization of “interiority” derives from a visual ideal—the monument that was the basis of exemplary pedagogy. Simply put, the notion that each man would emulate exemplars to become in turn an exemplar was based on the idea of gazing at, and then becoming, a monument, yet this rhetoric of monumentality led to the emergence of a problematized “hollow” interior. The monumental pose emerged earlier than either Martin or Egginton suggests the “modern individual” came into being: The new idea of prudence informed visual and textual representations from the fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries, and in each case, the monumental pose itself embodied the tension between inner feelings and outer behavior well before the Reformation articulation of sincerity. The shift toward the need for a more multivalent and ambiguous public persona (for example, in the Medici monuments’ lack of inscriptions and idealizing, nonmimetic statues) coincides with the self-conscious staging of the tension between two contradictory paradigms of understanding art, identified by Alexander Nagel and Christopher Wood.12 According to Nagel and Wood, the emerging “performative” notion of an artwork showing its specific circumstances of production drew attention to (or even “invented”) the previously dominant substitutional paradigm, in which visual patterns repeated across the centuries, with each instance somehow “participating in” the ancient (sometimes fictive) original. Although Nagel and Wood stress that the anachronic is specific to material artifacts, humanist exemplarity similarly posited an (ideal) unbroken chain of exemplars going back in time, with each one an instance of ancient virtue surviving into the present, and the whole series validated by this survival.13 At the same time, critics have argued that the rhetoric of exemplarity was inherently flawed: I posit that the staging of the failure of exemplarity corresponds (broadly speaking) with Nagel and Wood’s self-conscious substitution-performance tension, and that the two paradigms meet in the monumental pose.14 If the medieval image had “presence” while the modern artwork offers “representation,” the literary monumental pose sought nostalgically to convey the unmediated presence of ancient virtue while acknowledging that such presence was a representation all along. The various iterations of the pose, as proposed by writers on visual models from the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, ultimately failed to produce an adaptable but permanent self-image, leaving the interior of the subject exposed to the necessity of justifying adaptability rather than exemplifying timeless heroism.

Coining Oneself from Dante to Pisanello

The complexities of the quest for a concrete kind of glory start to be apparent if we return to Dante: In Dante’s text, Brunetto Latini supposedly teaches him self-eternalization through writing, which is closely compared with coining. Before the fifteenth century, coins showing the emperor’s image were the only models for autonomous secular portraiture. Coining also imposes form (a masculine act for Aristotle) on (passive, feminine) matter: Women were thus excluded from this process of self-monumentalization (as Dante’s audience would have taken largely for granted), and the various coining references to Brunetto, a sodomite, are profoundly ironic.15 In addition to the linkages between writing and coining in Inferno 15, Dante’s Convivio likewise emphasizes that words have the power to construct identities: Albert Ascoli has shown that the discussion of the true nature of nobility is part of the author’s agenda to acquire poetic auctoritas for himself.16 Dante was one of the earliest of the many fourteenth- and fifteenth-century writers to engage in the debate concerning noble identity and who thereby essentially appropriated the authority of arbiter of nobility.

Petrarch took up the challenge of “coining” oneself by giving some ancient coins to the emperor Charles IV, instead of the book Charles had requested, Petrarch’s De viris illustribus.17 According to Petrarch’s letter to the emperor, the coins bear “the portraits of our ancient rulers and inscriptions in tiny and ancient lettering, . . . and among them was the face of Augustus Caesar, who almost appeared to be breathing” (Fam. 19.3).18 The gift of coins is intended as didactic (Charles should imitate the Caesars depicted on the coins and so become worthy of joining the illustrious men in Petrarch’s book), and antihierarchical (it reverses the usual direction of patronage, asserting Petrarch’s autonomy and pedagogical authority). Petrarch’s strategy of coining Charles in the image of the Caesars failed, as Charles misread the coins as objects of economic exchange rather than texts (as Ascoli points out), and seems to have sent an image of Caesar back to Petrarch. Although it is unclear from Petrarch’s response exactly who the gift came from, Petrarch’s letter suggests that Charles was the sender, and mourns that the image of Caesar “would cause you, if it could speak or be seen by you, to desist from this inglorious, indeed infamous journey” out of Italy (Fam. 19.12).19 Petrarch clearly tried—and failed—to appropriate ancient artifacts in the construction of his relations to a powerful patron. His lack of success is partly attributable to his audience’s misreading the gift of coins and rejecting the exhortatory nature of lifelike portraits. Charles’s response disappointed Petrarch, who claims to have expounded at length on the pedagogical nature of his gift (Fam. 19.3). Yet this moment is profoundly important for the humanistic ideal of exemplarity: In a gesture meant to affirm his own authority, Petrarch proposed a visually accessible exemplar to be imitated; to his dismay, the artifact was appreciated not as an exemplar but as an object of value in and of itself—much like the Medici tombs, which self-consciously invite commentary on their value as beautifully crafted surfaces, rather than inspiring generations of men to imitate the two heroes supposedly depicted.

Petrarch’s own De remediis utriusque Fortune warns of precisely this problem: Reason argues that, although images of heroes may inspire men to virtue, they should not be cherished too much in themselves (De remediis 1.41). Yet while staying in Milan, the author “venerates” the tomb effigy of St. Ambrose “as though it were alive and breathing,” using language typical of ancient discussions of lifelike images, as though indulging in the veneration of beautifully crafted surfaces (Fam. 16.11).20 Yet while the author perhaps failed to venerate the saint rather than his likeness, and never managed to cast the emperor in the role of the ancient Caesars, another letter presents Petrarch as an exemplary model for a lowly goldsmith, who took the image of Petrarch as the inspiration for a new way of life: “He had begun spending a sizeable portion of his patrimony in my honor, displaying the bust, name, and portrait of his new friend [Petrarch] in every nook of his house, and carving his image even more deeply in his heart” (Fam. 21.11).21 Unlike the emperor, who willfully misunderstood the images of the Caesars, the aging goldsmith has sculpted the image of Petrarch into his heart, and proceeds to follow the author’s example by renouncing his occupation and instead taking up literary studies. In a more cha...