![]()

I

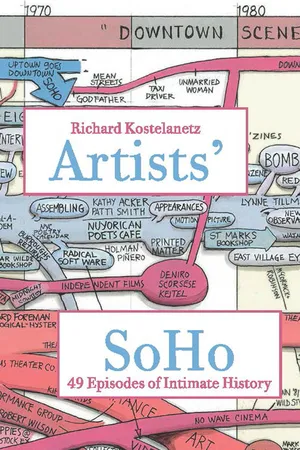

Although the creation of a single work of art may be an individual effort, artists have often clustered together to share ideas, offer mutual support, and provide a sympathetic audience for one another. The dynamics of rapid change in artistic styles over the past forty years have required that artists who want to remain current with the latest developments in art be close to the important galleries as well as accessible to others working in their particular field.

—James R. Hudson, The Unanticipated City (1987)

What I experienced in Artists’ SoHo was a cultural hothouse unlike anything anywhere else or any community before in American life. I’d already known about bucolic “artist colonies,” to be sure, but this was an urban oasis created not by a dozen or two artists but by hundreds, if not more, acting independently. As most of us got to know everyone in our buildings as well as many neighbors, SoHo eventually came to feel more like a one-industry town or a residential university campus than a typical urban neighborhood. Working the majority of our waking time on our art(s) we never needed to explain to our neighbors that nothing should get in the way of our art-making. No artists’ colony in the world was ever so populous, or even half as populous. None before had housed so many people soon-to-be distinguished in not one or two arts but several: painting, sculpture, photography, architecture, performance, dance, playwriting, music, even literature. Esthetically rich, deep, and various this ’hood certainly was.

As an artists’ colony, SoHo became an educational domain where, thanks to a certain generosity of spirit, younger people were inadvertently teaching one another all the time. Living there, at least at the beginning, was an intense learning experience, simply from going to openings, walking through galleries, and listening to our neighbors talk. The SoHo atmosphere was noncompetitive, in part because few of us saw our economies appreciate highly. Furthermore, whereas painters working in a similar style might have measured themselves against each other, many of us did art so original that we had no immediate competitors. Should anyone earn more from his art than others, he or she didn’t change his dress or behavior.

In my observation, visual artists, more than poets or composers, require professional social interaction to learn what cannot be taught in classrooms or gained from journalism about art. That accounts for why historians of painting so often write about groups or why visual artists rarely acknowledge teachers in their professional biographies, in contrast, say, to poets and especially composers, who nearly always do.

Painters and sculptors need to exchange esthetic intelligence and see important new works first hand, particularly at crucial points in their creative lives. Young visual artists are more inclined to influence each other, if not steal esthetic ideas or technical tricks from each other, than young writers, for instance. For the same reason that, say, Diego Rivera needed to go to Paris before World War I prior to returning to his native Mexico, so ambitious artists from around the world made their way to SoHo in the 1970s to look, to see, and to hear. One institution perhaps peculiar to artists’ communities is Artists Talk on Art, established in SoHo in 1975, where on many Friday nights, in a gallery usually, a panel is convened to address a certain theme. (Such weekly gatherings of New York City writers or composers are less likely.)

Painters and sculptors teaching in provincial colleges often rented SoHo lofts for the summertime, Manhattan’s notoriously humid heat notwithstanding, simply to assimilate what could not be learned back home. By contrast, aspiring artists who choose not to participate in this kind of art-center educational experience will forever reveal in their art, as well as their discourse, an absence of esthetic moxie. Simply, they don’t learn what surely not to do. As a de facto anarchist community, the university that was Artists’ SoHo was a school without walls with no tuition, no hierarchy, no tests, and no degrees; it had scant connection with the accredited university (NYU) just on the other side of Houston Street.

Another sign of SoHo’s de facto anarchy was the fact that no one planned or expected that it would become an artists’ enclave. City officials certainly didn’t. Nor did any arts institution or artists’ conglomerate. Nor did the art galleries or any major real estate developers. This sometime industrial slum became an art town thanks to the initiative of hundreds of independent individuals who seized a unique opportunity, some of them settling in outright violation of city law, as self-defined anarchists are predisposed to do, often against the advice of their lawyers.

I have met more than one aspiring artist who had been advised against purchasing in an area formally illegal for living. “You could lose everything,” their lawyer warned at the time, looking dumber and dumber in the years since. As artistic aspirations were more likely to enervate outside SoHo, more than once I thanked my lawyer father’s junior partner, a few years younger than I and then married to a painter, for approving a purchase that might have frightened a more conservative counselor.

Subtly perhaps, SoHo represented the culture of the 1960s without its radical politics (based at the time in antiwar protests). Everyone qualifying for an artist’s variance could buy into its co-ops regardless of age, race, gender, political affiliation, sexual orientation, ethnicity, or any other category of discrimination popular in the larger world. No one would have proposed any blanket exclusions, in part because they knew damn well they would be unacceptable. (Nor was “affirmative action” necessary.) Besides, no oldtime SoHo landlord thought he or she had property with enough value to require any cunning discriminations until the 1980s. Women owned nearly as often as men, and they renovated by themselves as well. In my own co-op, from the beginning at least one-third of the partners have been divorced, unattached women. Approximately one-third of my partners could be called gay.

Though artists are frequently described as predisposed to rabid radicalism (especially by conservative polemicists with fanciful imaginations), most of my neighbors were registered Democrats, if they cared at all, and conservative about property, especially if they owned, as I did, real estate through their co-ops. Though artists forged alliances within the community, no one was ever dubbed the “mayor of SoHo,” at least not for more than a minute for someone’s amusement.

Early in the history of my co-op, probably around 1975, one-third of my original partners had to fill out some official form that incidentally asked for our annual income. I recall noticing at the time that everyone had independently written $10,000. Even though some might have earned more, he or she didn’t want to invite unnecessary comparisons and thus envy. Cooperation counted more among us than competition, in part because downtown loft space was plentiful at least until the late 1970s. After all, artists were pleased to discover in their renovated industrial slum an agreeable alternative to the tradition of their isolation and alienation in America.

Many of my artist neighbors were indeed scraping by financially (and continued scraping for decades later). When artist couples split, it was not uncommon for them to divide in half their principal asset, which was their SoHo loft: one living on one side of a new wall that went to the ceiling and the other on the other side. Their kids, if they had any, would simply run down the hall to fulfill their legal obligations. (And when one divorcé moved elsewhere, this adjacent space was sometimes sold to the ex-spouse.) Indicatively, only one of my co-op partners, the least active artist, had the academic-bourgeois amenity of a country house until the late 1990s, when a second partner purchased one.

My hunch is that, in the hidden history of New York City, the subsequent boom in Manhattan and then Brooklyn real estate from the 1980s to the present originated in Artists’ Soho in the 1970s; but since the development of residential SoHo wasn’t planned by any prominent agency or real-estate mogul, no publicity-making entity could claim credit for turning the market for New York City real estate around.

![]()

II

Choosing a place to live has been for the American artist a problem of the first order.

—Harold Rosenberg, “Tenth Street” (1954)

When I came back to New York City from college more than fifty years ago, the area below Houston Street was an industrial slum that I might have walked through reluctantly on the way from Greenwich Village on its northwest to Chinatown to its southeast. Industrial debris littered streets that were clogged with trucks and truckers during the working daytimes but deserted at night. A few years before, Houston Street had been widened, destroying the structures fronting on the southside, leaving behind the unsightly sides of the chopped-off industrial buildings. On these walls several stories high were painted large advertisements; on the ground level along Houston Street were a series of empty lots less than twenty-five feet deep that were used for commercial car parking. The streets here were not numbered as in most of Manhattan but properly named: Mercer, Greene, Wooster, Crosby, and West Broadway ran from north to south; Prince, Spring, Broome, and Grand ran from east to west with a topographical geometry different from predominant elsewhere in the city. Though roughly observing a perpendicular grid initiated by the Commissioner’s Plan of 1811, these rectangular blocks stretched far longer from north to south than would be more typical north of Fourteenth Street,where blocks from east to west are longer than they are from north to south.

Until condemned by the city in the early 1950s, the area immediately north of Houston Street, running between Lafayette Street on the east and upper West Broadway on the west (previously called South Fifth Avenue, later La Guardia Place) and then as far uptown as West Third Street, looked roughly similar to the area below Houston Street. Once the industrial detritus was removed and some of its paved streets were eliminated, in its place came an impressive residential urban renewal complex called Washington Square Village with a private garden unusually large for Manhattan, all above a spacious car garage. Having built too high on the available property, the developer Paul Tishman was persuaded to give it to a “community institution” exempted from the rules entrenched in the Municipal Zoning Ordinance. The most feasible choice was New York University, on whose board of trustees Tishman incidentally sat. NYU has since used the Washington Square Village buildings to rent mostly to its faculty and staff. No private real estate developer ever again tried anything so big in the downtown neighborhood between Fourth Street on the north and Canal Street on the south.

“In the 1700s, the land that is now the SoHo district,” according to Charles R. Simpson, an early academic historian of Artists’ SoHo, “was largely a portion of the Bayard family farm, which stretched over hills and meadows from Canal Street up to Bleecker Street. During the Revolutionary War period, wooden palisades were built across the Bayard farm, and two forts were erected in 1776 on hills situated at the present site of Grand Street, marking the northern defensible limits of the city. The war left Nicholas Bayard, the farm’s owner, financially devastated, and soon after he was forced to mortgage one hundred acres west of the unimproved wagon road that was to become Broadway. This tract of farm land, comprising most of what became the SoHo district, was subsequently laid out in streets and sold in lots.”

In one crucial respect, SoHo resembled European cities such as Berlin, where I lived in the early 1980s, in that its streets were named in clusters reflecting a similar origin. Thus, Goethestrasse in Berlin was near Schillerstrasse, as well as other streets named after nineteenth-century German writers. Likewise in Berlin, Kantstrasse crossed Leibnizstrasse, both named after other German philosophers. SoHo was one of the few New York City places whose streets were named on a similar principle, in this case American generals from the Revolutionary War: Lafayette, Crosby, Greene, Wooster, along with Thompson, Sullivan, and MacDougal, whose names grace the north-south streets to the west of SoHo. The current exception, West Broadway, was originally named Laurens Street after Henry Laurens (1724–1792), a president of the Continental Congress. Any sophisticated Berliner landing in lower Manhattan could have instinctively figured that a street named after General David Wooster (1711–1777) must be near one named after the Marquis de Lafayette (1757–1834). (The names of SoHo’s cross streets have other origins.)

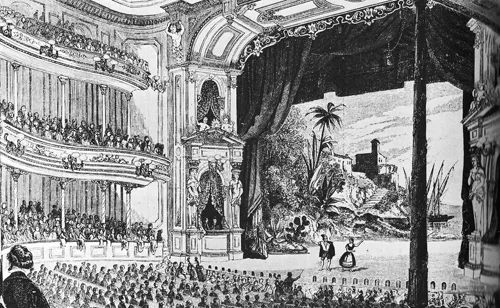

Niblos Theatre, built 1828.

Decades later, roughly a century and a half ago, this area below Houston Street attracted wealthy New Yorkers patronizing elegant stores and theaters on Broadway. “This was the Fifth Avenue of its day,” according to one guidebook. In the wake of minstrel halls came gambling casinos and eventually brothels, especially on the side streets. Maxwell F. Marcuse recalls in his This Was New York (1969) the beginnings of American bohemian life:

Walt Whitman … held forth at Pfaff’s celebrated cellar cafe on [653] Broadway just off Bleecker Street. Almost any afternoon or evening, hour on hour, would find this poet … pontificating on a wide variety of subjects while the genial host Charlie Pfaff hovered on the outer edges of the group of Whitmanians beaming ecstatically.

Other sorts of pleasure-seekers gravitated to this area at that time. In 1857, none other than Walt Whitman himself wrote: “After dark any man passing along Broadway, between Houston and Fulton streets, finds the western sidewalks full of prostitutes, jaunting up and down here, by ones, twos, or three—on the look-out for customers.”

As later with art galleries, so it was with brothels then. Some deserved more recommendation than others. The Directory of the Seraglios in New York (1859) offers this entry for Miss Clara Gordon at 119 Mercer Street:

We cannot too highly recommend this house, the lady herself is a perfect Venus: beautiful, entertaining, and supremely seductive. Her aides-de-camp are really charming and irresistible, and altogether honest and honorable. Miss G. is a great belle, and her mansion is patronized by Southern merchants and planters principally. She is highly accomplished, skillful, and prudent, and sees [that] her visitors are well entertained.

Regarding others, a popular guidebook from the time, James D. McCabe’s Lights and Shadows of New York Life (1872), warns that some of these women have male confederates who would rifle a customer’s clothing for his valuables while he is getting laid.

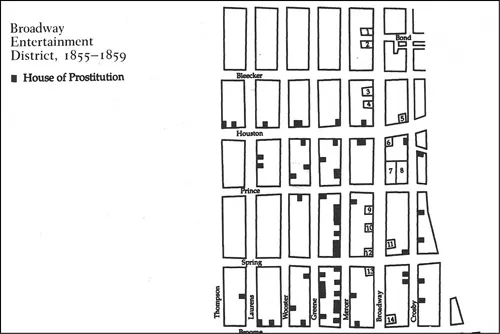

Prostitution must have been a big small business in Manhattan in the mid-nineteenth century. Perhaps ten thousand worked this trade, some of them part-time, according to Edward K. Spann in The New Metropolis: New York City, 1940–1857 (1981). In his classic study about nineteenth-century New York City prostitution, City of Eros (1991), the historian Timothy J. Gilfoyle writes, about a “rich collection of brothels … directly behind the hotels and theaters on both sides of Broadway, Mercer, Greene, Wooster, and Crosby streets.” In the 1870s, according to professor Gilfoyle, Wooster Street alone had twenty-seven whorehouses while fifty-two were on Greene. A century later not even art galleries were as numerous.

Broadway Entertainment District, 1855–59. City of Eros. Timothy J. Gilfoyle. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 1992, p. 121.

Whether prostitution or any other legally vulnerable activities (other than the Gay Firehouse) continued into current times in SoHo is an interesting question. On the one hand, consider that underpoliced, anonymous buildings provide incomparable opportunities for sub-rosa activities; on the other hand, any arrests for prostitution, gambling, or drug-smuggling in SoHo were scarcely noticed. The last observation could mean either that none existed, that no arrest happened, or that no arrest ever got publicity. In my experience, drug dealing was rare in SoHo per se, which didn’t have enough human sidewalk traffic except (on Saturday afternoons) to interest professional drug dealers, who tended instead to favor more populous locales such as Washington Square to the north or the Lower East Side. When for a brief period in 1992 a brothel prospered during a renovation at 43 Crosby Street, neighbors told local reporters that their SoHo block had suddenly become a “red-light district.” It hadn’t.

Most of the cast-iron buildings that came to mark the neighborhood for architectural historians were constructed between 1840 and 1880, generally for use by the textile industry. In Annie Cohen-Solal’s summary of enterprises in 1890:

Cheney Brothers, one of the world’s most prestigious silk manufacturers, worked out of 477–479 Broome Street, a cast-iron building designed by Elisha Sniffen. Mills & Gibb, the national’s largest novelty wholesaler, owned the John Correga building at the northeast corner of Grand and Broadway. W.G. Hitchcock & Co., a venerable import-export firm specializing in deluxe fabrics, had started in 1818 in the Griffin Thomas building at 453–455 Broome ...