![]()

1

CACOGRAPHY OR COMMUNICATION?

Cultural Techniques of Sign-Signal Distinction

SERRES AND SIGNS

During the eighteenth century the general concept of the sign acted as a point of departure for the subdivision of knowledge into aesthetics (with all its internal distinctions) on the one hand and philosophical and scientific disciplines such as economy and medicine on the other. In the course of the twentieth century, however, the sign fragmented into more or less sharply separated constituted components which, in turn, became the foundational basis for a number of autonomous objects and scientific disciplines. Among the discourses arising from the decomposition of the sign, three are particularly distinct: first, the discourse of mathematical or formal logic that speaks of symbols and formal systems or languages; second, the discourse of modern linguistics and semiotics that speaks of signs, of signifiers and signifieds, synchronic systems and diachronic change;1 and third, the discourse of communications technology that deals with signals and the physical properties of transmission conduits. While these sign disciplines are modeled on the natural sciences, the aesthetic and rhetorical aspects of the eighteenth-century semiotic discourse ended up on the side of the arts as objects of literary studies. In the early 1950s, in the wake of the new mathematical theory of communication, elements of information theory entered linguistic discourse. Saussure’s distinction between langue and parole was replaced by Roman Jakobson’s distinction between code and message—a terminology informed by the mathematical theory of communication and cryptology, that is, by World War sciences. In the early 1960s, however, the mathematician, philosopher, and historian of science Michel Serres proposed a simple, trifunctional model of the sign that moved the physical materiality of the channel—in other words, noise—into the center of philosophical and poetological reflection on the sign.

In his study The Parasite (Le parasite, 1980), Serres developed the concept of the parasite into a multifaceted model that makes it possible to employ both communication theory and cultural theory to arrive at an understanding of cultural techniques. This conceptualization of the parasite is particularly interesting because it combines three different aspects. First, there is an information- or media-theoretical aspect linked to the French double meaning of le parasite, which in addition to having the same meaning as the word in English can also refer to noise or disturbance. Second, by crossing the boundary between human and animal, the semantics of the parasite bring into play cultural anthropology. Third, the references to agriculture and economics inherent in the term introduce the domain of cultural technology. What strikes me as revealing from the point of view of the history of theory, however, is the fact that it was a reevaluation (carried out under the influence of Claude Shannon) of the Bühler-Jakobson model of communication that allowed Serres to sketch out a concept of cultural techniques capable of combining different methods and approaches.

Serres’s concept of the parasite emerged in the early 1960s when logicians were once again discussing the properties of the symbol. His initial point of departure was to replace Alfred Tarski’s categorical distinction between symbol, as defined by logicians, and signal, as defined by information theorists, with the very problem of distinction. That is, Serres inquired into the conditions that enable this distinction in the first place. According to Serres, the object of investigation for mathematics and logic, the symbol as être abstrait, is constituted by the cleansing of the “noise of all graphic form” or “cacography.”2 The conditions for recognizing the abstract form and for rendering communication successful are one and the same.3 Logic, then, appears to be grounded in a culture-technical fundament that is not reflected upon.

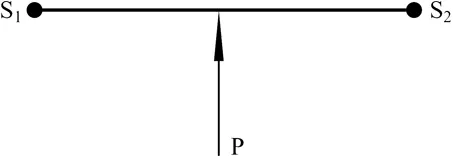

The concept of the parasite implies a critique of occidental philosophy, in particular, a critique of those theories of the linguistic sign and economic relationships that in principle never ventured beyond a bivalent logic (subject-object, sender-receiver, producer-consumer) and inevitably conceived of these relationships in terms of exchange. Basically, Serres enlarged this structure into a trivalent model. Let there be two stations and one channel connecting both. The parasite that attaches itself to this relation assumes the position of the third.4 However, unlike the linguistic tradition from Locke to Searle and Habermas, Serres does not view deviation—that is, the parasite—as accidental. We do not start out with some kind of relation that is subsequently disturbed or interrupted; rather, “[t]he deviation is part of the thing itself, and perhaps it even produces the thing.”5 In other words, we do not start out with an unimpeded exchange (of thoughts, goods, or bits); rather, from the point of view of cultural anthropology, economics, information theory, and the history of writing, it is the parasite that comes first. The origin lies with the pirate rather than with the merchant, with the highwayman rather than with the highway.6 Systems that exclude pirates, highwaymen, and idlers increase their degree of internal differentiation and are thus in a position to establish new relations. The third precedes the second: That is the beginning of media theory—of any media theory. “A third exists before the second. A third exists before the others.… There is always a mediate, a middle, an intermediary.”7

FIGURE 1-1. Michel Serres’ trivalent model of communication. Reprinted from Serres, The Parasite, trans. Lawrence R. Scher, 53.

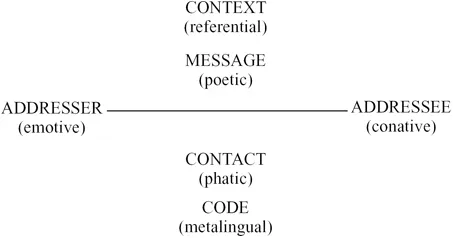

In Serres’s model of communication the fundamental relationship is not between sender and receiver, but between communication and noise. This corresponds to the definition of the culture-technical turn outlined above: Media are now conceptualized as code-generating interfaces between the real that cannot be symbolized and cultural orders. “To hold a dialogue,” Serres already wrote in 1964, “is to suppose a third man and to seek to exclude him; a successful communication is the exclusion of the third man.”8 Thus Serres inverts the hierarchy of the six sign functions in Jakobson’s famous model (Figure 1-2).9 It is not the poetic or the referential function that (according to the type of speech) dominates the others, but the phatic function, the reference to the channel. Hence in all communication each expression, appeal, and type of referencing is preceded by a reference to interruption, difference, deviation. “With this recognition the phatic function becomes the constitutive occasion for all communication, which can thus no longer be conceptualized in the absence of difference and delay, resistance, static, and noise.”10

The phatic function—that particular function of the sign that addresses the channel—was the last of the six functions introduced by Jakobson in 1956. Its archeology once again reveals the culture-technical dimension of the communication concept. It was first described in 1923 by Bronisław Malinowski, though he spoke of “phatic communion.”11 Using the communication employed during Melanesian fishing expeditions as an example, Malinowski—who in the wake of Ogden and Richards was working on a theory of meaning linked to situational contexts—developed a model of meaning that he called “speech-in-action.” Phatic communion, however, denotes a linguistic function in the course of which words are not used to coordinate actions, and certainly not to express thoughts, but one in which a community is constituted by means of exchanging meaningless utterances. When it comes to sentences like “How do you do?” “Ah, here you are,” or “Nice day today,” language appears to be completely independent of the situational context. Yet there is in fact a real connection between phatic communication and situation, for in the case of this particular type of language the situation is one of an “atmosphere of sociability” involving the speakers which, however, is created by the utterances. “But this is in fact achieved by speech, and the situation in all such cases is created by the exchange of words.… The whole situation consists in what happens linguistically. Each utterance is an act serving the direct aim of binding hearer to speaker by a tie of some social sentiment or other.”12 The situation of phatic communion is therefore not extralinguistic, as in the case of a fishing expedition; it is the creation of the situation itself. It is a mode of language in which the situation as such appears, or in which language thematizes the “basis of relation.”

FIGURE 1-2. Roman Jakobson’s six basic functions of language. Reprinted from Jakobson, “Linguistics and Poetics,” in Style in Language, ed. Thomas Sebeok, 353.

There are remarkable resemblances between Malinowski’s discussion of phatic communion and Serres’s theory of communication, according to which communication is not the transmission of meaning by the exclusion of a third. Malinowski observes:

The breaking of silence, the communion of words is the first act to establish links of fellowship, which is consummated only by the breaking of bread and the communion of food.13

Malinowski’s parallel between the communion of food and the communication of words establishes an intrinsic connection between eating and speaking that is also apparent in Serres’s model of the parasite.14 For Malinowski as well as for Serres, to speak in the mode of “phatic communion” is at first merely an interruption—the interruption of silence in Malinowski’s anthropological model and the interruption of background noise in Serres’s information-theoretical model. Communication is the exclusion of a third, the oscillation of a system between order and chaos. Without a doubt, the link between Malinowski’s phatic communion and Serres’s “being of relation” (i.e., the parasite) is Jakobson’s functional scheme that short-circuits the channel (in the sense of Shannon’s information theory) with Malinowski’s “ties of union”: “The phatic function is in fact the point of contact between anthropological linguistics and the technosciences of information theory.”15

For Serres, then, communication is not primarily information exchange, appeal, or expression, but an act that creates order by introducing distinctions; and this is precisely what turns the means of communication into cultural techniques. As stated above, every culture begins with the introduction of distinctions: inside/outside, sacred/profane, intelligible speech/barbarian gibberish or speechlessness, signal/noise. A theory of cultural techniques such as that proposed by Serres, which posits the phatic function as its point of departure, would also amount to a history and theory of interruption, disturbance, deviation. Such a history of cultural techniques may serve to create an awareness of the plenitude of a world of as-yet-undistinguished things that, as an inexhaustible reservoir of possibilities, remains the basic point of reference for every type of culture.

I will illustrate this using three examples from completely different media-historical constellations. The first example involves two elementary cultural techniques of the early modern age, the usage of zero and the typographic code; the second concerns the parasite as a message of analog channels;...