![]()

1

Reconstructing Jim Crow

In the summer of 1890, a reporter for the Philadelphia Times dispatched to Atlantic City interviewed white tourists about ongoing racial tensions publicized in the local press. Describing the insistence of many working-class blacks to demand admission to commercial leisure spaces, one white visitor echoed the sentiments of many in the beach town when he explained that while black workers often responded, “Alright, boss,” when told “you can’t sit here,” when it came to removing themselves from amusement rides and other consumer venues “they draw the line at the flying horses . . . If the flying horse goes they go on it, much to the disgust of the would-be exclusive patron.” With this statement, the white tourist expressed a common political complaint about the ambiguities of social space and economic rights in Reconstruction-era leisure settings. For much of the nineteenth century, racial disputes over access to public accommodations were often solved through violence, popular minstrelsy, and the politics of free labor, strategies and tactics that by 1877 had enabled white northerners to successfully contain the recreational and consumer behavior of African Americans. But beginning in the 1880s, the decision by black workers to demand access to public and commercial leisure spaces, and disputes among whites over how to stop them, unsettled long-standing northern segregation practices and exposed the fragility of racial solidarity and the limits of free labor ideology in a consumer-driven economy.1

The development of the Jersey shore for commercial and recreational use in the late nineteenth century paralleled the rise of mass consumption and the implementation of Jim Crow. Yet, as the early battles between white tourists, black workers, and business owners would prove, the politics of segregation in these vacation settings went beyond simple racism. The increased racial hostility also pointed to the changing social demographics of white crowds, the political and economic insecurities of white business owners, and the advent of consumer opinion in challenging free labor principles. Throughout the Reconstruction era, campaigns for “eight hours for what we will,” improvements in modern travel, and the promotion of beach resorts as middle-class retreats brought a new wave of white tourists to northern vacation settings. In response to the appearances and actions of black workers, white tourists attempted to evoke their power as consumers to shape public policy by calling on local authorities to officially institute segregation. Yet, to their surprise, the local business class often ignored their demands for segregation by refusing to engage white tourists and black workers in their disputes, a decision they believed would protect traditional social boundaries, retain the faithful services of black workers, and maintain the appearance of a free labor retreat.

Despite their desire to remain neutral, business could not ignore the increasingly problematic political power of consumer opinion in shaping segregation in the post–Civil War North. Unsure of how to employ the new racial language of the Reconstruction era in their promotional literature, in editorials, or on early segregation signs, local merchants and tourist promoters often ignored the charges of black impropriety and tolerated a limited African American presence on area boardwalks and beaches and inside amusement venues. Yet, to both black and white consumers, their refusal to promote either full integration or official segregation was viewed as sign of political weakness and came to reflect a postwar period where enforcement of the color line often appeared confused and unmanageable. In response, white and black consumers battled with one another and with local authorities in promotional brochures, pamphlets, and editorials to define the ideological and spatial boundaries of public and consumer leisure space. By failing to offer a coherent and consistent segregation strategy, business owners let local public policies fall victim to the volatile and shape-shifting whims of consumer opinion. It was against this unstable political backdrop that competing consumer and leisure discourses emerged and a new segregation debate took shape at the Jersey shore after the Civil War.2

In the summer of 1848, Rebecca Sharp accompanied her friend Henrietta Roberts for a weeklong excursion to Cape May, New Jersey, a popular beach town frequented by Philadelphia’s cultural elite. Like many antebellum-era contemporaries, Sharp and Roberts were part of a Victorian class of northern Americans—socialites, financiers, and merchants—who sought to escape the North’s raucous urban recreational spaces frequented by working-class patrons. Writing in her diary as they waited to depart, Sharp noted that the two of them would use their time at the shore to “stroll on the beach with a congenial spirit” and to “drink the sublimities of nature.” Come nighttime, they would “call on a social visitor for a midnight walk” or take a carriage ride to one of the many outdoor cottage parties. Sharp’s itinerary was a common one for well-to-do northerners, who used summer vacations to commune and relax with Victorian contemporaries in dining halls, outdoor verandas and hotel parlors and along promenades. In this noncommercial world of coastal bathing and public recreation, tourists and observers used summertime visits to beach resorts to remark on and bask in the free labor promise of social mobility, while scorning frivolous consumption and crude behavior.3

In contrast to other social arenas in the pre–Civil War North, patrons and onlookers marveled at the coastline’s remarkable ability to dissolve class boundaries. In the presence of the Atlantic Ocean, one observer explained, “human beings do not appear great” as “the garments in which they are attired are not designed to set off beauty.” Instead, as Frederika Bremer remarked upon visiting Cape May in 1850, “carriages and horses drive out into the waves, gentleman rise into them, dogs swim about, white and black people, horses and carriages, and ladies—all are there, one among another.” Such an idyllic scene she concluded, created a uniquely northern “republic among the billows, more equal and more fraternized than any upon dry land.” Olive Logan, who visited the popular beach resort of Long Branch, New Jersey, also admired the striving spirit and entrepreneurial vitality of the Jersey shore’s supposedly free labor utopia. Marveling at the foresight of businessmen to harness the powers of the sea for public recreation and economic gain, Logan exclaimed, “Long Branch illustrates a side of the American character that is a direct result of business energy, enterprise, shrewdness, and push.”4

“The Beach at Long Branch.” Appleton’s Journal, 1869.

Despite the testimonials of Bremer and Logan, antebellum resorts were notorious for their social exclusivity, keeping out unwanted and unseemly working-class excursionists, new immigrants, and free black workers. Thus, while the untamed waters of the seashore enforced a rough equality, off the beach, social status and class distinctions prevailed. Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper described the scene on a crowded promenade in Long Branch as one littered with “portly merchants, fresh from Wall Street and Broadway,” accompanied by “pretty girls in a halo of French rosebloods and kid gloves,” basking in the comforts of the “old fashion social style.” During the dinner hour, these gentleman and ladies would dine together in grand hotel ballrooms as a “regiment of forty negroes” marched in and out in perfect syncopation. As black waiters filled glasses, delivered meals, and cleared dishes, white patrons joked about innkeepers rubbing the dirt off the faces of white guests to “see whether they were serving Negroes by mistake,” utterances which reinforced the commonly held racial exclusions that defined Victorian leisure in the years before the Civil War.5

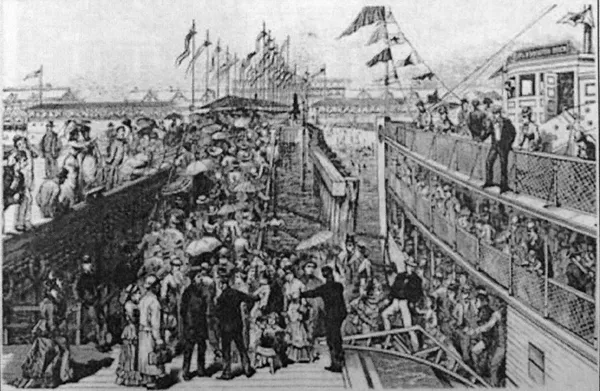

“Steamboat Landing.” Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, August 23, 1879.

Yet, while northern elites sought to limit access for working-class whites and black seasonal laborers, businessmen and merchants increasingly sought to extend the public sphere to an evolving white middle-class clientele during the 1850s. Saloons, ice cream parlors, dancing halls, billiard rooms, and horse-drawn racing competitions enticed summer guests who were no longer “interested in taking in waters” as their preferred recreational outlet. By the eve of the Civil War, these commercial changes to the seashore’s built environment spurred new conversations about access to public leisure spaces. As northern citizens coped with disruptions to the economy and the family, and struggled to understand draft riots and civil rights protests brought about by the Civil War, local commentators also debated who should use, control, work, and enjoy popular tourist sites. Following a financially sluggish tourist season in 1861, the New York Herald noted that “war like time, tries all things, and it has tried the watering places pretty severely.” While some observers optimistically reassured resort owners and businesses that “even civil war admits the possibility of people enjoying themselves,” others were less hopeful. “We are afraid,” some declared in June 1861, “this season will not be a very extensive or profitable one.”6

Shapers of northern popular opinion used the economic disruption of the early war years to transform the social profile and business practices of summer resort communities. “This war of ours,” the Herald declared, “is to revolutionize politics and politicians, to make the government stronger, to make the nation greater; to make business better and better conducted; to make us all more economical, prudent and steady—why may it not revolutionize fashion also?” For conservative northern critics, the specter of civil war provided an opportunity to correct the abuses by landlords that, according to one editorialist, ran “riot at watering place hotels.” Throughout the mid-nineteenth century, cultural critics complained that many popular vacation sites had increasingly abandoned the democratic spirit of the times by surrendering the “people’s welfare” to profit, charging exorbitant rates that failed to correspond to the increasing income inequality of the Jacksonian age. In particular, critics complained about the social climate of northern watering places that linked higher admission rates to the growing and pretentious “scepter of fashion” that forced “Jones to go because Smith went, and not because he liked it.” In its wake, many northerners hoped that the “rule of as your neighbors do” would be replaced with the “rule of as you like.”7

Efforts by cultural critics to strip northern beach resorts of antebellum-era social pretensions underscored efforts to remake the relationship between producers and consumers. Many hoped that consumer opinion, rather than the rules of free labor ideology and Victorian culture, would dictate personal enjoyment, social behavior, and rights of entry. Indeed, as unique social spaces, beach resorts challenged the critical principles of the free labor system. Throughout the early nineteenth century, northern intellectuals and Republican Party officials championed the regimentation of the industrial system and the promise of the wage labor contract as requirements for economic growth and personal freedom. In this producer-driven political economy, capitalists argued that great wealth derived from increased production, rather than the promotion of mass consumption. A holdover from an earlier republican ideal that scorned a political economy built on consumer luxuries, seaside resorts challenged these principles by equating mobility with pleasure, entertainment, and a “release from the conventional city life.”8

From the outset, Victorian skeptics warned northern travelers and politicians that the freewheeling spirit of watering places undercut free labor’s insistence on social restraint and frugality. Jersey shore promotional agents challenged these warnings by insisting that public recreation was necessary “for the man who has been caged for months in an office, reduced to a mere machine run for the purpose of churning out so many dollars per diem.” Yet, for conservative social critics, it was not just that vacations threatened to undermine the free labor work ethic, but that they also enticed normally responsible men and women to relinquish hard-earned savings on cheap amusements that they might of otherwise saved for future entrepreneurial endeavors. For a time, some critics were pleased that the Civil War unleashed a growing public distain toward fashionable resorts like Saratoga Springs and Cape May, which seemed deserted as northern vacationers chose “retired spots along the coast” or in rustic outdoor retreats. “Fashion has succumbed to mars. The War has revolutionized the watering places,” the Herald gleefully declared on August 23, 1863. “The war, which is reforming the manners, the dress, the society, the commerce, and the manufacturers, has reformed the fashionable also,” elevating the “healthful retreat” to a place of cultural prominence, while downgrading the preference for “artificial, enervating, corrupting” influences of northern watering places.9

By August 1863, the optimism of the previous summer faded as northern conservatives began to blame displays of fashionable elitism on abolitionists and black domestic workers. As northern whites confronted the national ramifications of emancipation, debates about class shifted to questions about the place of African Americans in leisure spaces. According to several white patrons, black domestic workers were beginning to use wartime emancipation as a pretext to harass white tourists, negotiate larger gratuities from summer guests, and enjoy their leisure time alongside white patrons. While many northerners came to accept leisure time as necessary for the physical and mental health of white wageworkers, they scoffed at the notion of extending such luxuries to black workers. As a result, conflicts over race and leisure in Civil War–era vacation settings contributed to the evolving historical debate about how to characterize black recreational behavior in northern popular culture. In marking black leisure workers as objects of fear and social disruption rather than amusement and comic relief, white northerners reconfigured the racial dynamics of public amusements during the Civil War. During the revolutionary era, theatrical depictions of the master-slave relationship were often violent and antagonistic. By the 1830s and 1840s, public depictions of African Americans’ recreational behavior and consumer habits shifted as promoters of mass culture and working-class audiences dealt with changes wrought by gradual emancipation, industrialization, and immigration. Minstrel shows, carnivalesque comedies, and traveling exhibits portrayed free blacks on stage, as well as in political cartoons and artistic essays, as social inferiors, whose bodies, movements, dialect, and cultural expressions represented a juvenile race that was to be mimicked, parodied, and pitied. These theatrical representations provided a retreat from the partisan politics of the Jacksonian age and the exploitation of wage labor, enabling a divided working-class community to unite around the cultural authority of “whiteness” by lampooning “blackness.”10

In their everyday encounters with whites, African Americans who participated in recreational outings received a much more hostile reception than black performers did inside minstrel theaters. In many antebellum northern cities, African Americans were routinely the victims of savage attacks from white gangs who viewed black leisure activities as a political reminder of the future of race relations during the era of gradual emancipation. More than perhaps other northern public venues, leisure spaces became violent battlegrounds where whites and blacks routinely squared off, proving that while popular culture representations of blackness promoted a narrative of subservience, the politics of the marketplace signaled that whites viewed black intrusions into entertainment districts as a serious public danger to be solved by violent force.

Such was the case in Philadelphia in 1828 when black couples emerged from coaches to a mob of angry whites who attacked a handful of the black women, stabbing their dresses with knives and shoving their dates into nearby gutters, while others frantically attempted to make their way into the night’s feature event—a subscription ball for the city’s black elite. Six years later, white gangs attacked local black residents attempting to ride a city carousel. Throwing stones at black riders and demolishing the “flying horses,” local whites expanded their assaults to surrounding black communities, marching down city streets with clubs, stoning black couples out for an evening walk, and attacking the homes and churches of other black property owners with clubs and “brickbats” in a campaign one rioter described as “hunting nigs.” Before city officials could contain the assaults, many black residents fought back, defending their properties and their right to enjoy area leisure venues in a three-day riot that exposed the seriousness with which many ordinary whites approached black recreation. In an era in which the fate of whiteness was tied to the defense of slavery in the South, whites also viewed black leisure as a growing affront to the widening economic divisions within the burgeoning free labor society. Relating the events of the era, Philadelphia’s popular press cautioned northern whites to be vigilant in maintaining clear divisions between workers and consumers. “How long will it be,” the Pennsylvania Gazette and Democratic Press asked, before “masters and servan...