![]()

Brazilian Machineries (or the Collapse) of Pleasure

Architecture, Eroticism, and the Naked Body

José Lira

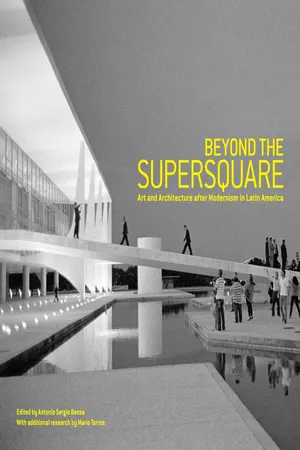

Since the early 1940s, Brazilian modern architecture has received worldwide attention. Its reception, however, has varied from laudation to opprobrium. From Brazil to the United States, from Europe and throughout Latin America, critics, curators, editors, and historians were either fascinated with its regional wisdom, formal inventiveness, and technical audacity or troubled by its frivolities and inconsistencies.1 As a result, a certain number of rather sophisticated and attractive works have entered the international canon to mold a certain image of Brazil’s contributions to the modern movement: the Ministry of Education headquarters in Rio de Janeiro (1936–43), the Brazilian Pavilion at the New York World’s Fair (1939), the Pampulha complex in Belo Horizonte (1940–43), the Pedregulho housing project in Rio de Janeiro (1946–52), and a few other satellite objects (mostly carioca in their DNA) would converge to establish a coherent narrative about the origins and development of Brazilian modernism and its sudden extinction soon after the completion of Brasilia.2

These representations and their historiographies have not been challenged and continue to operate on architects’ collective memory, imagery, and aspirations. What I have in mind here is to aim at one specific topos often remarked as a typicality of Brazilian architecture: its sensual overtones, an allegedly Brazilian characteristic—exuberant, extravagant, adventurous, irrational, instinctive, highly subjective—finding its epitome in the work of Oscar Niemeyer (1907–2012). Eventually praised for the mastering of a basic sexual duality while referring to a generic Brazilian woman as a sort of counterpart to nature, the tropics or a non-European bias,3 Niemeyer was recently proclaimed the “sensuous modernist.”4 His early refusal of straight lines, his seductive appeal to emotions rather than to judgment, reason, or logic, and his arrestingly sensual gestures or unencumbered spontaneity—all of which were the focus of the centennial celebrations that paid tribute to Brazil’s famed architect in 2007—have struck a cord since the 1940s.5

Indeed, Niemeyer has confessed to alluding to or drawing his inspiration from women’s bodies while exploring the plasticity of reinforced concrete in the curve lines and surfaces sinuously spreading out onto, or contrasting with, Rio’s lush landscape; at times, these forms would literally—or architecturally—allude to anthropomorphic fetish images. This body-mimicking operation in architecture appears to have provided the perfect antidote to a climate of international boredom with ascetic functionalism, where audiences were looking for fresh ideas and all too willingly indulged in the excitement and exoticism of the tropics.

In spite of the undeniable charm and fertility of Niemeyer’s drawing board—and the fascinating challenges his work has posed to the Western aesthetic, spatial, and constructive imagination—it always seemed to me that this topos was quite reductive; at least in regard to an understanding of his own work as well as an approach to the erotic theme in architecture. Not to mention the paternalistic and chauvinist outlook on Brazilians and women it entails.

The goal of this article is not to focus on such correlated narratives and self-narratives, but to follow some deviations and slippages out of them that might help push the discussion on eroticism in architecture in a different, less stereotypical direction. By examining two noncanonical works that were designed and built in the midst of the international hangover with Brazilian modern architecture, I intend to grasp some shifts from the canonical discourse on the body to other approaches, to its constructive rules and vital powers and motive, both visual and tactile, as in a work of art always rooted on space: João Filgueiras Lima’s Darcy Ribeiro Memorial, AKA Beijódromo (Kissingdrome) in Brasilia (1996–2010), and Lina Bo Bardi and Edson Elito’s Teatro Oficina in São Paulo (1982–84). These buildings may not be among the most outstanding architectural achievements in Brazil—nor among their designers’ own works—yet they embody the topic in mind with their provocative themes. Their elementary design gestures—basic forms, low technology, and hybrid materials—seem to challenge our understanding of modern architecture and its Brazilian counterpart. While operating some critical socio-technical and spatial devices, they call for the revision of our notions concerning the meaning of architecture and its relationship to the body—the physical and self-perceived body; the working body; the material body of things, buildings, and sites; bodies in buildings and around them; acting among other bodies, human and nonhuman.

Anthropophagic Techno-Eroticism

In June 1930, during the Fourth Pan American Conference of Architects, held in Rio, Flavio de Carvalho (1899–1973)—a Brazilian engineer who had studied in England and, since 1928, had become engaged with the São Paulo–based Antropofagia avant-garde group6—presented a thesis entitled “The nude man’s city.”7 The title was quite provocative for its time, and reportedly caused a stir in the audience. Carvalho launched a severe attack on what he called “the Christian concepts of family and private property,”8 ending with a plea to “the delegates of the Americas to cast off their civilized masks and to show their anthropophagic tendencies, which were repressed by colonization”—and by architectural education as well—tendencies that, according to him, were once “our pride and joy and possibility to stride without God to a logical solution to the problems of efficient urban living.”9 For Carvalho, the cities of the future made for the man of the future would be totally other than our bourgeois organism fit for the “Machine-man of classicism,” molded by repetition of ancient Christian rites, western taboos, monotonous routines, limiting desires, and sparing “no effort in annihilating all love of life, all enthusiasm to produce things, all desire to change.”10

Such an anthropophagic man—naked and free of scholastic taboos and outdated philosophies, free of reasoning and “to search for a mechanism of thought that would not block his desire to penetrate the unknown”—demanded a totally new urban mechanism: “a gigantic engine in movement, permanently at work, transforming the fuel of ideas into the needs of individuals, meeting collective desires and producing happy affections out of the understanding of life and movement.”11 This “anthropophagic metropolis” to be born in America (no longer as fortresses of colonial conquest) “will be a center for natural sublimation, for breathing life into worn-out desires; for production, selection and distribution of useful forms of energy to human beings, for research into the substance of the universe, into life, soul and the unknown.”12 Eroticism would thus play a vital role in this utopian model: an “erotic zone” being conceived “as a huge laboratory where a wide range of desires” would be “moving and stirring themselves in all directions, liberating energies, with no repression.” It would be a place “where the nude man” would “realize his own desires, discover new desires, shape his new ego, guide his libido” and “thereby reaching out . . . (to) the sublime anguish of the unknown in the non-metric changeability.”13

It is relevant to note that this local appeal to the primitive was in touch with French anthropology and avant-garde art at the time. Since 1922 Brazilian writer Oswald de Andrade (1890–1954), the main leader of the Antropofagia literary movement with which Carvalho would soon be associated, had been spending extended periods of time in Paris, where he seemed to have developed a taste for the primitive.14 In Paris he also met Blaise Cendrars (1887–1961), who had just published his Anthologie Nègre and who would become a regular visitor in São Paulo after 1924 and a close friend to many of the local modernists.15 Cendrars—like his contemporary Le Corbusier (1887–1965), another important reference to the Brazilian avant-garde—alluded to the potential cultural revolution in these nude men from South America: free of tiring labor and of all kinds of fetishes, open to the future, essentially antinostalgic, the opposite of a museum man. “L’homme tout nu,” writes Corbusier, had gotten rid of all external contingencies through the development of his own tools.16 We know through his American Prologue, written after his 1929 tour in Brazil, that he spent some time with the local anthropophagic youth, who introduced him to the idea of an indigenous rite of devouring collectively the flesh of the most valuable enemies, a rite of communion with those who had devoured their ancestors before them.17

A few years later, in 1935, when Carvalho himself had become a major leader of experimental art in town, Claude Lévi-Strauss (1908–2009) disembarked to Brazil to teach at the recently founded University of São Paulo. He would stay there until 1938, when he engaged on the only anthropological fieldwork he would ever endure throughout his life. His ethnological interests and antievolutionist beliefs—along with the missions he undertook among the Kadiweu, Bororo, and Nambikwara in Central Brazil—seem to have permeated the courses he would be in charge of in the city: they did cover a wide range of subjects comparatively treated, but clearly focused on the study of elementary forms of social life related to kinship, myth, and totemism.18 Although there is no evidence of contact between him and the local Antropofagia avant-gardists, a basic surrealist background seems to have operated on their common criticism of anthropocentrism.19

In tune with such appeals to fragmentation, alterity, and unexpected juxtaposition of cultural values, the anthropophagic avant-garde in São Paulo had a cosmo-corporeal connotation. As its Parisian counterpart it was intrinsically anticolonialist and antiethnocentric, refusing all monolithic national projects. Nevertheless, while standing for a cultural hybridism it would convoke the powers of technological civilization on the cosmological feast prepared by those who Oswald de Andrade called the techno-barbarian men. More than merely a ceremonial meal, anthropophagy would be proclaimed in the Anthropophagous Manifesto as a way of thinking, a “participating conscience, a religious rhythmic . . . the touchable existence of life, the pre-logical mentality to Mr. Levy-Bruhl study. . . . Routes. Routes. Routes. Routes. Routes. Routes. Routes. . . . (T)he permanent transfiguration of Taboo into Totem.”20 In other words, a sort of “metaphysics that imputes a primary value of otherness. More than that, which allows the switching of points of view between me and my enemy, between the human and the nonhuman. It would not thus be an exclusive attribute of the Tupi-Guarani peoples, but rather could be recognized as an Amerindian way of thinking and living,”21 that is, a kind of philosophy, which contemporary Brazilian ethnology has described as an “Amerindian perspectivism.”

Bodily Scales, Labor, and Pleasure

João Filgueiras Lima (b. 1932), AKA Lelé, is known to be the only example of an architect in Brazil able to assume the whole production chain of architecture.22 Indeed, his architecture is remarkably successful in terms of integr...