eBook - ePub

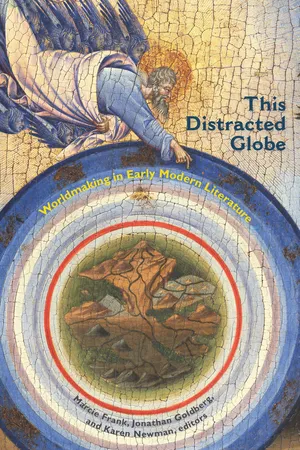

This Distracted Globe

Worldmaking in Early Modern Literature

- 256 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

This Distracted Globe

Worldmaking in Early Modern Literature

About this book

Worldmaking takes many forms in early modern literature and thus challenges any single interpretive approach. The essays in this collection investigate the material stuff of the world in Spenser, Cary, and Marlowe; the sociable bonds of authorship, sexuality, and sovereignty in Shakespeare and others; and the universal status of spirit, gender, and empire in the worlds of Vaughan, Donne, and the dastan (tale) of Chouboli, a Rajasthani princess. Together, these essays make the case that to address what it takes to make a world in the early modern period requires the kinds of thinking exemplified by theory.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access This Distracted Globe by Jonathan Goldberg,Karen Newman, Marcie Frank in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Literature & Medieval & Early Modern Literary Criticism. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Publisher

Fordham University PressYear

2016Print ISBN

9780823270293, 9780823270286eBook ISBN

9780823270309PART I

Materiality

CHAPTER 1

Worldly Muck: Translating Matter in Book 2 of The Faerie Queene

Brent Dawson

Spenser’s famous set-piece, the House of Alma, begins with a comparison of the human body and the world, the tangible physicality of what we all have and a vast expanse that stretches beyond its reach:

Of all Gods workes, which do this world adorne,

There is no one more faire and excellent,

Then is mans body both for powre and forme,

Whiles it is kept in sober gouernment.

(Spenser, The Faerie Queene, 2.9.1.1–4)1

Playing on the Latin sense of mundus as both “cosmos” and “ornament,” the passage suggests the body is a microcosm, that crowning jewel of the world most like the world’s own pristine beauty. The rest of the canto develops the synecdoche, expanding the human body into a well-run castle, the House of Alma, whose chambers and fortifications map precisely onto the different human organs. The integrity of the human body, its ability to regulate what it incorporates and expels of the outside world, is made the model of well-run government. As here, the body and its matter are tightly interlinked throughout book 2 of The Faerie Queene with ideals of politics and empire: the temperate body is a colonial fortress; the pursuit of gold is appetite in the Cave of Mammon; maritime adventure verges on self-pleasure at the Idle Lake; acceding to sexual desire is going native in the Bower of Bliss. These organic metaphors serve ideological ends, naturalizing capitalism and imperialism as forms of civilizational health and rendering savages and other cultures as disorders to be contained or overcome.

But can these analogies among body, state, and world move in directions less comforting for imperial ideology? How might flesh, with all its traditional attributes of mutability and impurity, open different ways of thinking politics in Spenser? Jonathan Goldberg raises the possibility of such a reading of the house in The Seeds of Things, arguing that while the practices of bodily discipline explored in the canto “easily correlate with colonialism,” given that colonialism claims to bring order to civilization’s unruly outsides, if one follows the affirmative possibilities Foucault’s later work finds in these regimes, “such linkages do not exhaust the work of these labors on oneself.”2 The possibility Goldberg raises, that Spenserian flesh might cut across the boundaries raised by colonial ideology, is supported by Spenser’s longest description of the matter of the body in the Alma canto, which compares human flesh to the cosmopolitan Tower of Babel:

Not built of bricke, ne yet of stone and lime,

But of thing like to that AEgyptian slime,

Whereof king Nine whilome built Babell towre;

But ô great pitty, that no lenger time

So goodly workemanship should not endure:

Soone it must turne to earth; no earthly thing is sure. (2.9.21.4–9)

Where the canto as a whole dwells on the body as a beautiful and exemplary structure, these lines shift focus toward the viscous matter of which that structure is formed. While the shape of the organism might be beautiful, the matter within it is given to rotting, never permanent or “sure.” The passage raises a number of perplexing questions: Why, in a celebration of organic form, this sickly lingering on the body’s rotten flesh? What is the relation between the two opposed functions of flesh in the passage, composition and decomposition? Finally, what links together the fatal weakness of the body with which the stanza ends and the dream of a united humanity suggested by the reference to Babel in its middle? Does the lowest form of ecstasy, the body’s dissipation into dirt, and the highest, humanity’s transcendence over all barriers of linguistic, political, and religious difference that divide it, bear some relation here?

For several recent readers of The Faerie Queene, the House of Alma has offered a privileged point from which to re-evaluate Spenserian materiality. Stephen Greenblatt’s influential reading of the poem emphasizes Spenser as a Protestant poet who rejects the sensuous pleasures of the body for the sake of disciplinary control in the service of the Elizabethan state.3 Working against the dualism implicit in Greenblatt’s reading, Michael Schoenfeldt argues that the House of Alma reveals the productivity of the body in Spenser. The canto’s detailed attention to digestive and defecatory processes indicate, for Schoenfeldt, a self fashioned through the maintenance of the body.4 David Landreth likewise focuses on the generativity of slime in Alma’s house, comparing it to Aristotelian prima materia, the shapeless substance out of which all living and nonliving forms arise.5 The house offers, in these critical accounts, an Ovidian body less reified into singular form than dynamic and in process; the self in such accounts is not pre-given and “manacled” to a corporeal inhabitance, as in Marvell’s “Dialogue between the Soul and Body,” but is made and unmade through bodily processes and practices.6 For a late capitalist society that insists on classifying bodies in ever more specialized and pigeonholed ways, the appeal of Spenser’s mutable flesh is obvious. Yet these interpretations raise some questions: there are seemingly dualistic moments in Spenser, like the beginning of the Alma canto, that argue that the body must be kept in “sober gouernment,” presumably by the rational mind, lest it “growes a Monster” through “misrule and passions bace” (2.9.1.4, 1.7, 1.6). What would such readings have to say about these moments’ insistence on the disorderliness of the body’s flesh? Are they the signs of a residual religious asceticism from which Spenser could not entirely detach himself? Or is the body’s unruliness tied in Spenser to its self-fashioning power?

These critics’ affirmation of the generative potential of Spenserian flesh is also qualified by how they divide good and healthy forms of matter from other, less pleasant or valuable varieties. Schoenfeldt finds Spenser’s account of slime in the passage quoted above unappealing and inharmonious with the overall sense of the canto: there is “a tension between the unqualified awe the form [of the body] inspires . . . and the sinful matter from which the form is made . . . Spenser’s humanist constructionism chafes against his Protestant disgust.”7 That abrasive, noxious stuff perhaps recurs in what Schoenfeldt sees as the “superfluous excrements” separated from the “matter which nourishes” the body later in the canto.8 For Landreth, slime is the prima materia of Alma’s house, holding “boundless potential for nourishment,” but contrasts strongly with the “sterile” gold in Mammon’s cave, whose illusory bounty can only “ape[] the body.”9 Such divisions between healthy and unhealthy, fertile and sterile, kinds of matter need to carefully avoid duplicating the terms of the traditional division between matter and form. Is it possible to give a non-dualistic account of matter in Spenser that is not so, well, idealizing? The critical interest in the productivity of matter in the canto, I argue in what follows, is complemented and, at times, challenged by the importance of slime as a material that is useless, decaying, and toxic. For the corrosive power of slime is bound to a miraculous generativity, a generativity unlike ordinary production in being unpredictable and uncontrolled. Spenserian slime thus inhabits the paradoxical space where corruption and creation intertwine. This paradoxical materiality opens some alternative, queer possibilities for how sexual desire is understood in Spenser, as well as for a non-imperial universality in the muck out of which all life, of whatever culture or species, is made.

In critiquing Marxist materialism, Georges Bataille raises similar questions that guide my inquiry here. Bataille points out that materialism, as it has traditionally been thought in philosophy, is another form of idealism, a foundation for an orderly and systematic way of understanding the world.10 (A quick way of making this point is that “matter” is itself an idea with a long philosophical history; try to disentangle idea from matter and one brings it back in a concealed form.) Marx’s reversal of the Hegelian dialectic, substituting matter for spirit, nevertheless still borrows the framework of idealism, seen in its teleological drive toward universal humanity. Bataille calls for a base materialism that revalues the traditionally negative attributes of matter as rotting, disgusting, and impure, for it is precisely these qualities that resist idealist thinking and get at what is most material about materiality. Bataille thus examines those taboo bodily materials most often invested with symbolic value—blood, particularly menstrual blood, feces, ejaculate—noting the ambivalence these substances hold across cultures, being both degraded and invested with tremendous power. Where idealism conceives all society and individual life as having purpose, continuing ever onward toward the receding horizon of its end, Bataille’s base materialism attends to those activities and desires in life that seem useless and without purpose: sacrifice, luxurious consumption, ritual, and so on. Bataille develops this thinking of materialism into a theory of sexuality, where sexuality is defined not in terms of healthiness or (re)productive purpose but its ecstatic shattering of the controlled self, the abasement of life as purposeful before its ultimately meaningless end.11 That materialism also flows for Bataille into a theory of politics in which society on the model of the stable and productive organism is overturned in favor of a focus on the useless social expenditures found in rituals and the practices of the lowest members of society, its “dregs.”12 How can matter, for Bataille or Spenser, be toxic at the same time as being generative? How does such an understanding of matter affect questions of desire, sex, and reproduction? How might it open a non-imperialist thinking of universality not reliant on rigid categories of the “human” or “nature”?

Slime

Of the nine times Spenser employs the word “slime” in The Faerie Queene, a single word is rhymed with it in a majority of cases: “crime.” When Christ is incarnated, he is described as “in fleshly slime/Enwombed . . . from wretched Adams line/To purge away the guilt of sinfull crime” (2.10.50.2–4). Spenserian slime thus alludes to the Christian doctrines of the flesh and of original sin carried by the flesh, as articulated by Augustine and others. The beginnings of the doctrine of original sin are found in Paul’s statement that “by one man sin entered into the world, and death by sin; and so death passed upon all men” (Rom. 5:12).13 The word translated as “flesh” in Paul, sarx, is one of several terms Paul uses for the body, soma being the most frequent other term. But whereas soma denotes the body as an organism, an orderly arrangement like the Greek kosmos, sarx is something quite different. Etymologically, sarx is likely connected to sairo, “to draw,” “to draw off,” and suggests the meat that can be stripped away from the bones. The flesh is an excess of the skeletal order of the body. Fleshly life in Paul leads to what Goldberg, commenting on Arendt’s reading of Augustine, calls “doubled existence” and reads in relation to Foucauldian askesis, a fundamental division of the self that allows the self to continually remake itself through a process of will and resistance.14 When Paul states, “I am carnal, sold under sin. For that which I do I allow not: for what I would, that do I not; but what I hate, that do I” (Rom. 7:14–15), he figures this divided state as the self’s entrance into commercial relations. From the start, the self is not master of itself but “sold under sin.” For Paul, then, matter is fatal to the self, splitting and sinking it into a network of relations that alter it. The connection between sin and selling highlights Paul’s association of material existence with movement, exchange, and transaction, what he generally refers to as the “the world.” As Rudolf Bultmann notes in Theology of the New Testament, at a certain remove, “‘flesh’ becomes synonymous with the term ‘world.’”15 The world, described in Paul through phrases like “the princes of this world,” “the riches of this world,” and the “pleasures of the world,” and set in antithesis to God’s kingdom, is being insofar as being is passing, both into relations with others and into nonexistence. “The fashion of this world passeth away,” Paul declares, in a statement that is not only eschatological but definitional (1 Cor. 7:31). One need not hear this statement as an orientation toward a transcendental other world, for Paul is quite circumspect about any character of the world to come. Rather, Paul ties the mortal condition of the body, its ecstatic dissipation of itself in death, with the cosmic, the totality of existence in the world.

As the Pauline allusions around the word suggest, the “slime” that forms the temperate body of Alma’s house is not as healthy and orderly as the above critical accounts claim. While Landreth interprets Spenser’s “slime” as the nutrient-rich mud of Egypt, it is unlikely that is the primary signification of the word in this passage.16 As the eighteenth-century editor John Upton notes in his gloss on the word, “The slime used for cement to the bricks, with which Babylon was b...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Preface

- Introduction: World Enough and Time

- Part I. Materiality

- Part II. Sociality

- Part III. Universality

- Acknowledgments

- List of Contributors

- Index