![]()

CERTES A SACRIFICE

I didn’t want to go to Certes and there I was on my way side by side with my brother I’m forever doing what I didn’t want to do I thought I am in a state of sin it is Easter the first day of passing over instead of passing over to my side I pass to the other—looklook how beautiful it is my brother was saying I looked

the boats on their sides in the silted up channel slack time the sea has withdrawn we make our way between hundreds of tipped hulls I see them as dead I see them as tuna gasping for breath, a posthumous landscape. I found it unbeautiful, a still life, the graveyard scene, from my brother’s perspective: the simple life devoid of unpleasantness the empty hour invisible fishermen gone to lunch says my brother

I am in a state of sin I always do what I didn’t want to do, right away I do everything I didn’t want to do, sin spreads out over my whole heart, on all sides a feeling of being sucked into the mud grips my thoughts, the square notebook tucked into the left pocket of my shirt weighs on my heart as if it too were quickened by regret, on my right on my brother’s side too I am in a state of sin

We walk side by side Pierre walks I sin on all sides, him dry shod me in mud

each time I’ve wanted to get back to writing and I’ve wanted to write at all costs I have left the book behind, I have even left my own life behind and entered a country I didn’t want to be in,

at the very moment writing, the right, the country, the visa had been granted me after having been taken away and forbidden me for years, the very day “my life” as I call literature had been given back to me, the other, “life,” suggests I go the other way, and I go, I can’t help it, it’s stronger than my desire, this other desire I am, a ghost I don’t see bars my life and the very day I wanted at all costs to go to my life Igoto the other.

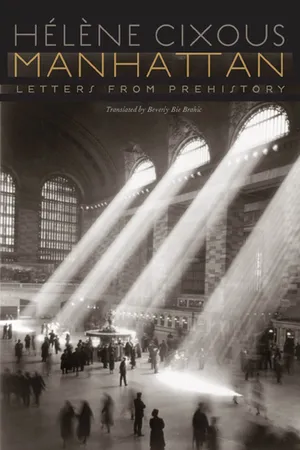

To think it took me forty years to discover Certes on my doorstep my brother was saying you’ve got thirty kilometers of road between the salt ponds, it’s extraordinarily beautiful, he exults in his discovery and I am in a state of sin I was thinking I’m losing New York to the salt ponds I thought I was going to get there today thirty-five years it’s taken me to get to the New York book, looklook this virginal sky in which I see feeble flickers of Manhattan’s skyscrapers drowning, the huge simulacra that had so fascinated me getting covered up by the heartrending softness of Certes’ silk

once again I do what I didn’t want to do and it is I nonetheless therefore an other who is doing this to me I thought the personal pronoun has been betrayed I came here to write The Story, as we call this book that is slipping out of my grasp, this very day was stamped on my calendar months ago I’ve been through weeks of quarantine I’ve put up with boredom fear inanition thanks to this day’s date, knowing the name of the day of deliverance is itself a release, finally it comes, Time keeps its word, the door to my mental prison swings open, and me does not come out, I am not in my life, I catch the plane for the book, but instead of finding myself safe and sound at my desk, I see myself in reality on the road to Certes walking to the left of my brother like a madwoman, like some hostility come out of my back, a wicked angel puts me in my place legs unsteady leaning on my brother whom I love I drag myself to the rack without admitting it, it’s not that I am giving in to my brother it’s worse than that, murkier, I myself lock myself up outside myself, I make myself flee, I do exactly what I didn’t want to do and not what my brother wanted, I don’t even do what my brother wants but what my opposite wants although (1) clearly I did not want to go on this outing to Certes (2) for seven months I’ve been waiting at all costs for this day to come, awaiting it for decades but less wholeheartedly, and now the day goes by without me in front of me, a cool, healthy, breezy April day, I could jump, take it on the run, my brother isn’t forcing me, when I told him as we arrived in Certes I don’t want to go to Certes he responded tactfully we’ll go wherever you want. We took the road away from Certes, toward the Ocean. Where the road crossed the highway I said: let’s go to Certes. And my brother took the direction away from the Ocean. He was happy to do as I wished, but the sin was already sinning in all directions again, against me against my brother, against my will. What’s left of my will is in my left breast pocket the little notebook which throbs, against my heart—divided, like a heart. I seem crazy to myself I see clearly that nothing is clear in my confusion, supposing I speak to my brother who will it be speaking to him?

I am still astounded by the violence of my reactions, I tell myself. You run along between the strings of boats lying like so many dead fish, clinging to your brother as if you dreamt the end of the world might catch up with you in Certes. Certes is nothing but a hole after all. You are astounded? I am astounded by your astonishment. Didn’t you yourself wake her up, the one whose presence or absence you so dread?

And that was thanks to your brother, unintentionally, with his unintentional help. He’s a doctor after all, unintentionally, but still.

She who was running like a madwoman between two rows of inert bodies because, or so she thought, she was in danger of losing her mind and felt she should make her way to the exit as fast as possible was the same me whom I had lost or who had lost me violently, brutally, in the USA in 1965, she who was me, a liberated woman, strong, solid, proud of descending from my sensible mother, having inherited her sense of direction, which had suddenly persuaded me to plunge into the absolutely interminable labyrinth that snakes under the City of New York, I’m not interested I said whereupon I nevertheless found myself winding through kilometers of underground tunnels, kilometers of gut tiled in bizarrely shaped white terracotta, sometimes standing up often bent beneath the too-low ceiling, sometimes flattened so as to glide like a letter through the slot, it would take weeks, I’ve got other things to do I said they’re waiting for me in my country, I have children, a family, which way to the exit I asked. Exit? You have to find it, if there is one. In thirty-five kilometers said the advertising voice, male, husky and encouraging. Few people know the underground. How did I get there? Special delivery. Recommended. Like that last letter, addressed to New York, to New York in person, by this me, encysted or so I’d thought after 1965’s abscess, but in fact merely dormant and always ready to wake up a demon since the day she’d totally done me in, swiftly and violently, in 1964, a blow or two in New Haven to start then in Buffalo, then right after that and fatally in New York, this me lodged in the seismic depths of me, inactive for decades, then capable of crushing everything without warning some night, had committed the suicidal error of turning back to Certes when, to please me, my brother had given up the idea, perhaps because he had given it up, without our realizing that in doing so he was giving free reign and unhoped-for encouragement to my annihilation urge.

I thought of her, my fearsome; I think: she’s on the rampage. This strength, tangled up in my roots, which is perhaps one of my roots, never gives me time to talk back. She’s a bolt from the blue. One of those “other powers,” those omnipotence-others on whom Proust and his mental denizens must have bestowed this vague enigmatic and therefore terrifying and utterly essential name during the havoc wrought by the passage of Hurricane Albertine. They are unleashed in the cataclysm. They are us, we don’t know them, once they’re on the loose it is best to face the truth: we haven’t the strength to tame the omnipotence-others. The solution—medicine, acknowledging their superiority whenever it meets up with them—abdicates reason and consents to a mad collaboration, says the soul doctor. Intelligence reasonably sides with madness. Abdicate, I told myself, such in its wisdom is folly’s advice. I was having a problem with this. In my little logbook I wrote the word: abdication. Lacking a cure words rush to the rescue.

In tiny letters I scribbled: “The first time I abdicated was that famous first of January 1965 in New York there was a snowstorm, I was astray just as the world (the whole world) was astray.”

Reasonably, I abdicated reason, I conceded the superiority of the omnipotence-others.

These other-powers came on the one hand from the other-realm, on the other hand from a world that has always had absolute power over me: literature.

These lines fit on a page of the Idea notebook 5 × 5 with little squares, the smallest you can find. My ideas-on-the-run must therefore fit this format. I note my brother standing up me hunched on a stump, Gulf to Certes road.

Idea miniaturizes the violence of my flashes.

Another sample Idea: note of April 1, 2001:

Right away after the disappearance

of my son George

I left Bordeaux

and right after that

Paris as well as the whole rest of France

Where my three friends

G(eorge) G(eorge) and G(eorge)

Remained, without news of me.

Besides it was only

much later I noticed

(to tell the truth last year)

the coincidence of the names

What I like about my brother I was thinking is his doctor’s presence, there’s a doctor in my brother, walking along beside him I am aware of the doctor at my side, this allows me to be sick, at my brother’s side I am in the place of illness but mental, but shyly it’s not something I boast about, still this is understood in our conversations and in our silences, in our intensely chaste complicity,

that it is not impossible for the human being to be mental, to be mentally strong or weak, strength is weakness and vice versa in this domain is something we never discuss but whose existence as a hazy and undeniable region in our vicinity, we have acknowledged from the beginning of time

we never mention it, but still surreptitiously between us there’s a password of sorts, the bizarre name of Clos-Salembier, often we say Clos-Salembier, as if we were speaking of the Algiers neighborhood in which the two of us were shut up and nailed down together over forty years ago but these vocables are loaded with implications whose explicit inventory we have never compiled,

to say “Clos-Salembier” is to suggest and invoke several successive universes all endowed with anguish fury and excitement. From time to time “I find myself back in the Clos-Salembier” says my brother and we know. Whenever my brother says “I find myself back in the Clos-Salembier” I know he is lost, surrounded and embattled, and me too consequently for the one drags the other down with him and vice versa. The minute I say “I find myself back in Manhattan” we are prey to exaltation. We say “I find myself,” this means I am lost, lost in the unfathomable depths of some incarceration whose keys we cannot locate.

But in another way it is only fenced in the Clos, in the jagged confinement, in the Salembrian bites and lacerations that my brother finds himself, a kind of reflexivity that only his self-portrait gives back to him and me too therefore, if he finds himself forever there too I find myself assailed, me with the same with my brother chained as if by enchainment, for in the Clos, the enchantment was caused and redoubled by the enchainment, we were never without chains, especially our lives’ two essential chains: (1) the chain of the dog, our one and only dog, the soul, the angel of our daily outing; (2) the chain of the gate to which all the time the whole spirit of our destiny (which we only knew later) was linked and all the family ties, above all the supreme tie with our beloved wizard, the figure of our young father, forever and to this day sublimated, the key to heaven’s constellated gate, the cover of The Book, the gods’ frail shadow on earth, the born-revenant, always already a revenant even when he wasn’t dead, always ghostly and never really there, even at home he was somewhere else to our two alert minds it was obvious he came back to us from profound sojourns among the dying the dead and the ill including the mad. But we never breathed a word of this not me to my brother nor vice versa. We called this delectably ghostly sensation “Clos-Salembier” (Manhattan in English). My father was a madman according to my mother to this day she can’t fathom how having such authority being so princely, reigning over the apartments and the whole family and beyond, how being waited on first by his mother granny my grandmother just like the sacerdos to whom she served a bowl of couscous each time she made couscous, for him and him alone, descending in majesty from the fourth floor on which she lived to the third floor where my father had made his home, thus bringing from the higher floor to the lower which was highest of all because it sheltered her son our father and in third place my mother’s husband, and then being waited on by Omi my maternal grandmother along with my mother, and then obeyed and worshipped by us, how on earth this holy saintly never questioned extremely authoritarian doctor could always right up to the day of his death have been so credulous, credulous to the point of death, to dying of it, absolutely, absurdly confident in—it struck me as completely idiotic says my mother, yourfather the idiot, at my age I don’t feel the need to hide what I think and always with great vigor and clarity, it’s too bad it’s the age at which the past grows a little vague but my judgment sharp as ever: Myfather the idiot was worshipped as lord of the manor everything handed to him on a silver platter and in a golden cup, my wizard father.

—How can you trust someone who has confidence in everyone? This question will dog my mother to her dying day. My-father was idiotic in the First War some blindly idealistic people were enthusiastic about sacrificing themselves, says my mother, I have no idea what my enthusiastic-to-the-end father thought I haven’t yet figured out whether he believed he owed Germany something, someone ought to have told him: Charity begins at home, my extraordinary but nonetheless war-idiot of a father yourfather had the same flaw, despite being considerably more authoritarian than me, yet another war-blind the Second one, yourbrother too tortuous thinking appeals to him, communism, what an idea not one I’ve ever had illusions about, flaws in reasoning suddenly you’re at war men believe in it being basically much more authoritarian than the average, I still haven’t figured out whether they believed or whether they believed they should believe.

You too eyes shut always full of confidence blinded by confidence to the point of believing in that shady American. You inherited the intelligence of my Hungarian grandfather on my father’s side who used to rise at five in the morning and read the Talmud. You rise at five to read but the woman who goes around the farm on horseback and has no faith in anything is me. One cannot read without believing: you read you believe.

—It’s not all right I thought, it’s not going to be all right, I tell myself, I can walk along beside my brother as much as I like, we’re not in step, the ungluing has begun, the ancient unavowable persecution, I keep my feet moving one after the other while underneath it’s sizzling, the doubling up has begun. Don’t think about it I thought, it’ll stop, stick to your brother, don’t think about not thinking, stick, stick, stick

—Look at those people says my brother, looklook-at-them-those-people-over-there I love them my brother exclaims, directing my gaze at a group of hikers that my brother contemplates ecstatically, look at them hiking and not harming anyone, trooping along toward the salt ponds, see how lovely it is, I looked and saw the troop, beings of all ages and shapes, having boots and backpacks in common, naked calves of all sizes and degrees of hairiness as well, some with walking sticks with all sorts of hairdos some with gray or greasy or no hair at all looklook how beautiful they are says my brother, I’m looklooking I say I don’t believe in it, I thought, I have no faith in hiking, I looked at the hikers and saw them as I was supposed to see them and I go on seeing them as they are I thought, ugly awkward cheerful about as lovely as Hieronymus Bosches in the self-destructive state into which I was sinking as I snaked along beside my brother

looklook how they glow with health, how good human nature is out of doors, my brother rejoiced, meanwhile I was thinking just the opposite I have lost all contact with the medical world, he reiterated, each time we go for a walk, he makes a point of saying this, as if to renew a vow made despite himself. The hospital? I go up the stairs. I’m tightening the screws. If I’m still on staff there three days a week it merely goes to prove I have totally broken with them, at the hospital I’m tightening the screws.

It is certainly true that my brother no longer wants to be a doctor, not ever again, I’m leaning on the doctor he himself has dismissed, whom I keep safe as we wend our way back up the slippery slopes, I slide my arm into the ring of my brother’s arm and I prop my stumbling thoughts on the doctor-in-hiding-driven-out on his own orders, he claims his medical past was a long state of wandering for decades he wandered playing the medicine-man, day after day for thirty years he saw himself in a lab coat and stethoscrope in vicissitude he says, right up to the day he tears the coat off and throws down his stethoscope, for you must throw it, into the trash, a gesture no doctor has ever before committed, a gesture one may take as comic but which I cannot conceive of without shuddering, tears come to my eyes at the thought of this smashing of the icon, at the thought of this cruel inflicting but courageous but cruel

I picture myself throwing down my pen, the one I am gripping between the three live fingers of my right hand right here right now which I love like the flesh of my pet cat, this pen which waits for me and breathes life into me and vice versa I picture myself as my brother flinging it to the ground, deliberately, and cutting it off from me along with the three fingers it is attached to and that desire it and squeeze it as a blind man his stick of light and it’s as if I pictured myself in a moment of great madness putting out my own eye the one that reads in other words my right hand, and in order to do so having reached that state of total dissociation which renders self-mutilation possible; and seeing myself commit such madness I want to run away from myself, I want to drag myself away, I want to crack open my head and take out the brain

the way I see it my brother has committed or accomplished or executed the most terrible act of all, he has driven the doctor out of himself therefore health, sense, authority, science, wisdom, and even philosophy itself, he has divided himself up, accused judged expelled all or par...