![]()

1. Heteronymies of Lusophone Englishness: Colonial Empire, Fetishism, and Simulacrum in Fernando Pessoa’s English Poems I–III

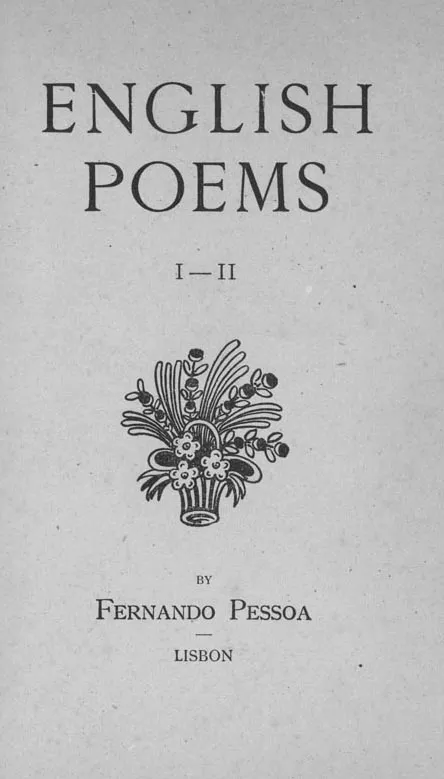

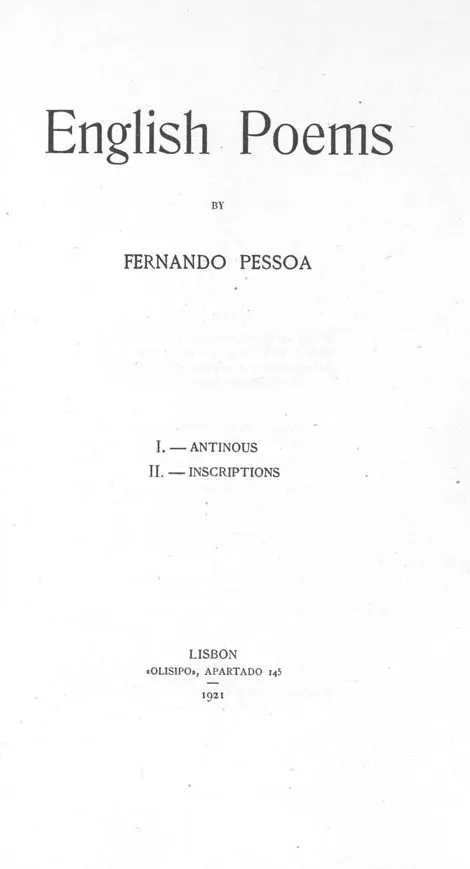

The Portuguese poet Fernando Pessoa (1888–1935) started writing poetry in English at roughly thirteen years of age with a poem titled “Separated from thee . . .” (1901) while he was living in the colonial town of Durban, South Africa. At about the same time, Pessoa had already adopted one of his first transpersonal identities as Alexander Search, an early English entry in his long series of fictional personalities (personalidades fictícias) (Obras em prosa, 92) that Pessoa referred to as “heteronyms,” which would gradually generate Pessoa’s extremely diverse oeuvre. This chapter examines the way in which the origin of Pessoa’s transpersonal tendencies, connected to his decried impossibility to write in “my own personality,” is intrinsically connected to his critically overlooked poetry written in English during the second decade of the twentieth century.1 More specifically, I analyze the way in which the tradition of English literature that Pessoa gradually absorbed during the early years of his life in South Africa functioned as a direct precursor to the heteronymic project that configures his radically idiosyncratic modernist poetics. Ultimately, I will show how the publication of Pessoa’s English Poems in 1921 should be critically reconsidered a crucial event in the evolution of the work of perhaps the most seminal Lusophone author since Luis de Camões (1525–1580)—both in terms of Pessoa’s impressive bilingual ability to produce poetry in English and in his attempt to incorporate his own poetic work into the canon of English literature.2

Pessoa referred to his literary alter egos as “figuras de meu sonho” (dream figures), “gente” (people), and “subpersonalidades de Fernando Pessoa ele-mesmo” (subpersonalities of Fernando Pessoa himself) among other related appellatives (Obras en prosa, 92–93). As opposed to the term pseudonym that has an implication of a false or spurious personality, Pessoa’s use of the term heteronym (heterônimo) to categorize this series of literary personae not only emphasizes the heterogeneity of the names it refers to but also their relational form with the other linguistic terms to which they are intrinsically linked. This crucial term refers to Pessoa’s fictional personalities as concrete entities in the way they are related to him, in fact as translational terms intimately linked to, but ultimately independent from, the orthonymic term Fernando Pessoa ele-mesmo (Fernando Pessoa himself). As the French philosopher Alain Badiou argues in his reassessment of Pessoa’s work within contemporary philosophy and literary theory in Handbook of Inaesthetics, Pessoa’s invention of a “non-classical logic” is precisely grounded on the “language games” and “borrowed codes” that ultimately articulate what Badiou refers to as “the heteronymic game”:

Pessoa proposes the most radical possible form of the equation of thought with language games. What is heteronymy, then? We must never forget that the materiality of the heteronym is not of the order of the project or of the Idea. It is delivered [livrée] in the writing, in the effective diversity of the poems. . . .When it is all said and done, what is really at stake is the production of disparate poetic games, with their own rules and their own irreducible internal coherence. It could even be argued that these rules are themselves borrowed codes, so that the heteronymic game would enjoy a kind of postmodern composition. (Badiou, 40)

Based on Badiou’s reconceptualization of Pessoa’s heteronyms as emerging in the act of writing, I argue that the publication in Lisbon of Pessoa’s English Poems —a three-volume poetry collection that he authored as himself and that has been generally ignored by Pessoa scholars until very recently—constitutes a decisive event in the critical reexamination of Pessoa’s work. It is precisely in the complex linguistic nature of Pessoa’s English Poems and, in particular, the paradoxical relation that the Portuguese author establishes with the English language and literary tradition, that we explicitly encounter what Badiou defines as “the materiality of the heteronym” (40).

In the light of Badiou’s comments above, I will demonstrate how Pessoa’s English Poems enacts the very heteronymic logic that articulates his overall work in Portuguese. Specifically, I focus on how these poems function as part of a linguistic game that is “delivered”—livrée, as Badiou states in the original—through a poetry that plays with and translates “borrowed codes,” in particular the foreign “codes” configured by the English language and literature that Pessoa absorbed while living in colonial South Africa under the educational system imposed by British colonial rule. In other words, the extreme importance of Pessoa’s English Poems resides in the way it allows us to see more clearly how his development in Portuguese of a system of heteronyms is rooted in an idiosyncratic poetic and linguistic response to the English literary tradition that literally emerged heteronymously into a new version of itself—in fact, as a translation of English poetry. As his English Poems shows, Pessoa was able to translate the linguistic and poetic codes inherent in his English colonial identity into a powerful heteronymic matrix that would ultimately lead him to develop his extremely original and influential mode of literary modernism.

Pessoa in South Africa: The Colonial Encounter with Englishness

The young Pessoa spent about nine years of his life in Durban, which is now the largest city of the KwaZulu-Natal province of the Republic of South Africa. Pessoa arrived in South Africa in 1896, following a long Atlantic voyage in which he left Lisbon together with his then recently remarried mother to settle in Natal with his stepfather João Miguel Rosa, commander of the Portuguese army and consul of Portugal in Durban. At the time of Pessoa’s arrival, Durban was the economic and political center of a colonial state established and run by the British on Zulu territory since 1843, after Great Britain had taken over the Boer occupation of the Zulu kingdom approximately ten years earlier. Durban was then a small and highly segregated colonial town run by a community of white European settlers who governed a society that included indentured Indian laborers, as well as a very large majority of Zulu natives.

One of the most relevant aspects of the historical circumstances that determined Pessoa’s life in Durban is the fact that his education was shaped by the schooling system established by the British colonial government. As Robert Morrell argues in his sociohistorical study of the colonial period in Natal, the establishment of a British education system aimed primarily at forging a unified cultural identity for a diverse European population of white settlers:

The identity was forged around British cultural symbols and the English language. The schools, for example, were modeled on British public and grammar schools. The sports that were played were taken from Britain (cricket, soccer and rugby) or the empire (polo). German, Norwegian, Scottish and Irish settlers all gradually adopted the English language and became assimilated into the settler community. An important feature of settler identity was whiteness and its presumed association with civilisation and racial superiority. (Morrell, 53)

As a member of the European settler community in Durban, the young Pessoa had to adapt culturally and linguistically to an imperial form of Englishness—the only identity available to him apart from his relatively small Portuguese familial circle. Pessoa’s British education in Durban not only enabled him to have an impressive command of the English language at an early age but also provided the means for him to articulate a new cultural identity parallel to his native Portuguese self that I will refer to here as a “Lusophone Englishness.”3 This particular aspect of his life in Durban is essential for understanding the way in which Pessoa’s Lusophone Englishness became a catalyst for the heteronymic poetic system that informs his entire literary production in Portuguese. In short, Pessoa was able to develop an English identity through the discipline of English studies, the main source of Englishness to which he had actual access in Durban. Pessoa’s early assimilation of a colonial Englishness was primarily determined by his readings of the work of canonical English poets, among them Shakespeare, Milton, Pope, Byron, Shelley, Wordsworth, and, as I shall discuss below, Keats and Spenser.4

As a crucial part of British colonial ideology, the main corpus of English poetry at the core of English studies formed a fundamental basis for the education Pessoa received at Durban. Although originally established at different cities in England through Mechanics’ Institutes and Working Men’s Colleges during the first half of the nineteenth century, English studies soon became a vital ideological tool for incorporating individuals into the socio-economic project of the British Empire.5 It is worth noting that English literature was in fact part of the examination for the entrance to the Civil Service of the East Indian Company during the late 1850s, becoming instrumental for the ideological training of the government workforce, the settler communities, and the colonial subjects of the British Empire.

Terry Eagleton has already suggested how the rise of English studies during the second half of the nineteenth century was essential in order to incorporate new recruits to what he refers to as an English “‘organic’ national tradition and identity.” As Eagleton describes, “What was at stake in English studies was less English literature than English literature: our great ‘national’ poets Shakespeare and Milton, the sense of an ‘organic’ national tradition and identity to which new recruits could be admitted by the study of the humane letters” (Literary Theory, 28). It may thus seem that the literary works belonging to the canon of English studies that Pessoa originally experienced in South Africa succeeded in recruiting him to that very same “organic” English national tradition mentioned by Eagleton in a rather straightforward way. However, Pessoa’s peculiar position within colonial Durban as both a member of the white European settler community and as a subject of a British imperial ideology ultimately foreign to his native Portuguese identity led him to develop an extremely paradoxical heteronymic relationship with the specific form of Englishness he assimilated while living in South Africa. Although English language and literature constituted a heteronomous structure that was imposed on the young Pessoa by his particular historical circumstances living in a British colony, his heteronymic logic produced an idiosyncratic modernist idiom that managed to translate both the a priori originality of English literature and the inherent “organic” national identity at the very core of English studies described by Eagleton into a multiple series of heteronymic versions. In what follows, I will demonstrate how Pessoa’s poetic writing constitutes a heteronymic translation of “Englishness” as an imperial identity into a paradoxical poetic project with extremely important theoretical implications for the study and critical reassessment of his work in general, as well as its impact within Lusophone, European, and Anglo-American modernisms.

Pessoa’s English Poems: An Imperial Cycle of Erotic Love

Pessoa’s most impressive literary response to the specific cultural, linguistic, and intellectual challenge brought forth by his assimilation of an imperial Englishness was embodied in the two collections of English poems he published in Lisbon in 1921, respectively titled English Poems I–II and English Poems III. The first volume contains Antinous, a long poem that was composed around 1915 and published as an independent volume in 1918, as well as a series of classically oriented epitaphs titled Inscriptions. In English Poems III, Pessoa published Epithalamium, an earlier long poem composed around 1913, eight years after his permanent return to Lisbon from South Africa in 1905. A prominent aspect of the publication of Pessoa’s two editions of his English Poems is perhaps that, except for Mensagem, his 1934 nationalistic collection of Portuguese poems, these three poems together with an English collection of Shakespearean sonnets, titled 35 Sonnets (1918), constitute the only poetry collections that Pessoa published during his lifetime under his own name.

Pessoa composed the poems included in English Poems between 1913 and 1921, precisely the period in which his main heteronyms emerged in his writings. In fact, the poetic production of his different heteronyms follows a serial progression of different poetic eras that emanates from the source of pagan poetics developed by the heteronym Alberto Caerio in his O Guardador de Rebanhos, and that culminates in the neopagan systems developed by his various heteronymic followers, as Pessoa describes here:

Este Alberto Caerio teve dois discípulos e um continuador filosófico. Os dois discípulos, Ricardo Reis e Álvaro de Campos, seguiram caminhos diferentes; tendo o primeiro intensificado e tornado artisticamente ortodoxo o paganismo descoberto por Caerio, e o segundo, baseando-se em outra parte da obra de Caeiro, desenvolvido um sistema inteiramente diferente, e baseado inteiramente nas sensações. O continuador filosófico, Antônio Mora (os nomes são inevitáveis, tão impostos de fora como as personalidades), tem um ou dois livros a escrever, onde provará completamente a verdade, metafísica e prática, do paganismo. (Obras em prosa, 82)

Alberto Caeiro had two disciples and a philosophical follower. The two disciples, named Ricardo Reis and Álvaro de Campos, took different paths. Whereas the former intensified Caeiro’s paganism, turning it into an orthodox aesthetic system, the latter—based on another aspect of the Caeiro’s work—developed a completely different system founded entirely on sensations. The philosophical follower, named António Mora (their names are as unavoidable and externally imposed as their personalities), still has one or two books to write in which he will prove the absolute truth of paganism from a metaphysical and practical level.6

According to this passage, the heteronyms Ricardo Reis and Álvaro de Campos soon emerged as the two necessary disciples required for the poetic development of Alberto Caeiro’s primit...