![]()

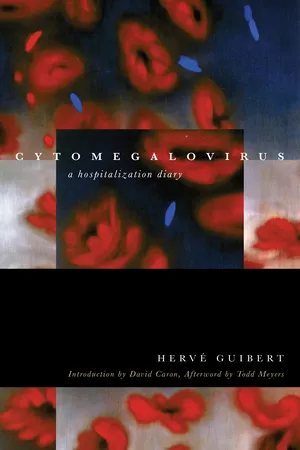

Cytomegalovirus

A Hospitalization Diary

September 17

Vision in my right eye is shot: difficulty reading. Listen to music: not yet deaf.

September 18

A young woman with a very beautiful, made-up face, who looked a little Asian, lying unconscious on an abandoned stretcher in a radiology corridor, very red lips, and something on her uncovered neck which I at first thought was a wound, as if someone had tried to cut her throat, but which apparently turned out to be a long smear of lipstick.

Waiting behind a window before the abdominal ultrasound: you can see the hospital visitors descend the escalator and move toward one ward or another. Many men of all ages talking to themselves, agitated. The old ones in pajamas and robes. The young ones often bare-chested under an open shirt or jacket.

Cytomegalovirus! Hospitalization.

Lenses right on the retina.

I’m afraid they’ll make me sleep in paper sheets, under a synthetic blanket.

The will to live—marvelous or sickening?

They used to tell me: “You have beautiful eyes,” or “You have beautiful lips”; now, nurses tell me, “You have beautiful veins.” The doctor, a young woman with a foreign accent who took the abdominal ultrasound, tells her assistant, who is leaning over her shoulder in front of the screen: “Look at how beautiful that is!” And to me: “You have a truly exceptional and very rare interior configuration. We are also going to take some pictures for ourselves.”

September 19

The sheets are not made out of paper, the blanket is not synthetic: good, old, used hospital sheets, a real wool blanket, from a hospital or barracks.

No shower in the room (now I realize that this terror of a communal shower, one which has no privacy, stems from my childhood), no towels in the bathroom. H.G. tells me that the nurse’s aide almost choked with indignation when he asked for one. Paper towels. B. and H.G. insisted on buying me a real towel. They also brought back a small spoon, a little box of sugar (my Briard whole milk yogurts in glass jars, which are in a refrigerator with my room number—365—on them, in a small room next door, “the best in the world,” says B.). They also brought me black grapes, my good friends.

The window allows permanent viewing from the corridor into the room. I don’t say anything. B. says: “All you have to do is push the closet door.”

Young, vaguely Asian intern, extremely kind and competent. She says she knows Claudette Dumouchel, I tell her, laughing, “I promise I won’t write Le protocole compassionnel #2, so you can relax, we can have a nice relationship.” We joke. She asks me if I have written lately, and I say yes: “Something which has no connection to AIDS and which I’ve never done before, a very physical love story between a man and woman, what’s more, a very exotic novel, that’s why I went to Bora Bora!” We ask each other what we like about our respective professions, that’s good. I ask her: “If, for one reason or another, they hadn’t detected the cytomegalovirus right away, how long would it have taken me to lose my eye; would it have taken months, weeks, days?” “Days,” she answers. We may not be able to save it as it is, we’ll see!

Weakness, fatigue, I leaf through the papers, no desire to listen to the radio that I asked H.G. to bring. No time to get bored, always a caregiver passing by, or the telephone.

T. asked what I see from my windows, I move around the room telling him: “A beltway on the outskirts of town, a little forest, a truck rental and repair shop, the hospital parking lot, some trees. And, in the distance, Paris.”

Dietitian (I asked to see her when I arrived) also kind and competent. A half hour of back-and-forth questioning. I gorged myself this evening, on the tray I found the menu typed on the word processor, I hid it under the dish of grapes so I could copy it. Better than Air France.

Start an intravenous line. They hook me up to an old crock that doesn’t even move. This severely reduces my ability to move around the room. I try to do a lot of things in the same place (pissing and brushing my teeth, for example) so as not to have to make too many trips. But I’ve already asked two nurses to scrounge up an IV pole that moves. I’ll keep asking until I get it.

At dinner: only one spoon for both the soup and the farmer’s cheese, I ask, on principle, if they expect me to clean it with my tongue? Special treatment.

Obviously can’t find the buzzer, always been awkward. And—I don’t know how—I tangle the intravenous tube around the pole, soon I’ll only be able to move a few inches.

They warn that it will hurt, they prick a very large needle in a painful spot, almost at the wrist, to leave the upper veins free for blood draws. I asked the intern to have the kindness to instruct that they only draw blood if absolutely necessary, and not on the slightest whim, as they often do in hospitals.

Writing is also a way of giving rhythm to time and a way to pass it.

I’m waiting for them to do the IV (I love adopting the pro lingo—with cytomegalovirus, they won’t do an LP, lumbar puncture, on me), I’ll get it lying down, it is eight in the evening, I’m tired. It’s been a long day. Till tomorrow.

I get up to jot down some phrases that swim through my head, or else they’ll haunt me until tomorrow. The cries of suffering which come from nearby rooms are almost more heart-wrenching than one’s own suffering. The neighbor screams, the nurse tells him, “Open your mouth wide,” I wonder what she can possibly be doing to him.

Today, I may have made the acquaintance of the room in which I will die. I don’t like it yet.

You have to wait between five and ten minutes after buzzing, you have the impression that the nurses go on a one-shift wildcat strike so they can steal away on roller-skates to party at the La Rumba nightclub in the Auchan superstore.

The room hasn’t been disinfected or even swept: old bandages under the bed. Proof. The nurse to whom I mentioned it hurries to gather everything to throw it out. She says, “It’s disgusting.” And I say, “You’re not going to mark it as evidence.”

D. always said that M., who was going to die anyway, died much more brutally because he was hospitalized in a room that hadn’t been disinfected so as to keep the hallway clear. Hospital illness.

When a nurse installs my IV, I can’t help but think it may be water, “since in any case, he’s going to croak,” and remember the three lesbian nurses of Tübingen who liquidated old geezers by sticking a little spoon under their tongues and flooding their lungs.

The sleeping pills seem like amphetamines!

Z. told me that she would bring me a soft light; personally, I love this leaden, blinding white neon.

The War Diary of Babel: if I lose my eye, it will be one of the last books I opened. This diary should also be a war diary.

On the admission form this afternoon, three options: “stretcher,” “wheelchair,” “can walk.” I still can.

Midnight. I got up to pee, they would have woken me up anyway to take my temperature, my blood pressure. The kindly nurse, the one who deplores my non-moving pole and with whom I can relax and have a nice time, installed a hep-lock in me (after the “vein protector”), the instrument I needed so I could move around, that I had been asking for since six o’clock of the little crabby blond nurse, who told me it didn’t exist here. The heroes and villains, just like in fairy tales.

There’s an eye at stake.

“Open your mouth! Did you hear me?” asks the big nurse. “Yes, what are they doing?” Answer: a mouth rinse. The Tübingen nurses.

They gab away all night without lowering their voices in the room next to mine, about salaries and the cost of living. I’ll have to call my accountant one of these days.

A hospital stay is like a long voyage with an uninterrupted parade of people, of deliveries, or of rituals, to pass the time. There isn’t even any more night.

Hospitals are hell.

Much later at night, they lower their voices a little, even they are tired.

Screams in the next room, like bellowing cows. No way to get some sleep.

September 20

They always wake you up at seven o’clock in the morning to stick a thermometer under your armpit. At eight, five tubes of blood taken through the hep-lock. The morning nurse seems nice. There are pearls, and there are swine. Yellow sun through the window.

One could write a humorous dictionary of AIDS term: the candidate is a fungus that declares he’s running so he can take over your throat, your esophagus, your stomach...