![]()

1: King of the Mountaineer Musicians Fiddlin’ John Carson

I’m the best fiddler that ever jerked the hairs of a horse’s tail across the belly of a cat.

—Fiddlin’ John Carson, “Who’s the Best Fiddler?” (OKeh, 1929)

In 1923, a middle-aged former textile weaver nicknamed “Fiddlin’ John” Carson unexpectedly helped to launch a new genre of American popular music at an experimental recording session in downtown Atlanta. There, inside a vacant loft converted into a makeshift recording studio in mid-June, he recorded two selections for the OKeh label—“The Little Old Log Cabin in the Lane” and “The Old Hen Cackled and the Rooster’s Going to Crow.” The producer of the session, OKeh A & R (artist and repertoire) man Ralph S. Peer, of New York City, was less than thrilled with Carson’s performance. Carson’s fiddling was competent, if a bit rough and idiosyncratic, but Peer reportedly found his singing to be “plu-perfect awful.” As the story goes, Peer refused to release either of Carson’s recordings commercially until Polk C. Brockman, OKeh’s Atlanta record distributor and talent scout, promised to purchase the entire first pressing of five hundred copies. Carson sounded “so bad,” recalled Peer in a 1938 Collier’s magazine interview, “that we didn’t even put a serial number on the records, thinking that when the local dealer got his supply, that would be the end of it.” But Peer was mistaken. One month later, he was astounded to learn that Brockman had sold out of his entire stock in a matter of a few days and had wired the company to order additional copies. With Carson’s record selling briskly in Atlanta, Peer assigned it a label number in the OKeh catalog and released it on the national market in August 1923. Eventually, the disc sold an estimated several thousand copies. And although neither Peer nor Brockman, nor even Carson himself, realized it at the time, they had just set in motion a commercial music revolution.1

Carson’s debut record marked the advent of what OKeh would soon designate as a new field of recorded commercial music called “hillbilly music,” or, less pejoratively, “old-time music.” The modest but surprising sales of this record indicated to Peer and his superiors at the General Phonograph Corporation, the manufacturer of OKeh records, that a promising, previously unrecognized market existed for old-timey grassroots music sung and played by ordinary white southerners. “One of the most popular artists in the OKeh catalog is Fiddlin’ John Carson, mountaineer violinist, whose records have met with phenomenal success throughout the country,” the Talking Machine World, a phonograph dealers’ trade journal, reported in April 1925. “When Mr. Carson’s first OKeh records were released it was expected that they would be active sellers throughout Southern territory, where this artist is a prime favorite with all music lovers. However, to the keen surprise and gratification of the General Phonograph Corp., the records by Fiddlin’ John Carson not only attained exceptional popularity in the South but were received cordially by the public everywhere.” Within two years of Carson’s debut recording session, Columbia, Victor, Vocalion, and other northern-based phonograph companies were marketing similar old-time discs to record buyers not just in the South but throughout the United States. “The fiddle and guitar craze is sweeping northward!” proclaimed the splashy headline of a June 1924 Columbia ad. “Columbia leads with records of old-fashioned southern songs and dances.” By the end of the 1920s, hillbilly records had become big business for the nation’s talking-machine companies, and between the peak years of 1927 and 1930, more than one thousand new releases in this genre appeared on the market every year. Clearly, the southern fiddle breakdowns, sentimental ballads, and stringband selections captured on record by OKeh and other labels resonated with music lovers across the nation during the late 1920s.2

Although many country music historians credit him with waxing the first commercially successful hillbilly record, Carson was not the first traditional white southern musician to make commercial recordings for a major record label. A. C. “Eck” Robertson of Texas, Henry C. Gilliland of Oklahoma, and (possibly) Henry Whitter of Virginia had all entered recording studios three months to a year before Carson did. Nor did Carson succeed because he was a particularly gifted musician or singer, as Peer himself had quickly recognized. In fact, most of Carson’s Atlanta contemporaries, especially younger, more popular music–oriented fiddlers such as Lowe Stokes and Clayton McMichen, regarded him as a mediocre bowman, at best. “He was an awful fine guy,” recalled McMichen, “a poor fiddle player, but he sold it good—good showman. And he was a good, good man.”3

Carson managed to succeed where previous musicians had failed chiefly because of two significant historical transformations that had reshaped early twentieth-century Atlanta. Momentous economic and social changes had swept through the Gate City of the New South in the decades immediately preceding Carson’s debut recording session. Between 1900 and 1920, Atlanta’s population had skyrocketed (more than doubling, from 89,872 to 200,616), and many of the newcomers, like Carson himself, were rural white migrants who had flooded into the city to work in its booming cotton mills, factories, and railroad yards. Carson’s first record found a receptive market among these transplanted working-class Atlantans, who, like industrial workers throughout the modern South, were then an increasingly important but generally overlooked consumer group. Only recently had southern workers’ newfound purchasing power thrust them into the vibrant commercial mass culture of Hollywood motion pictures, radios, Victrolas, and Model T Fords, and now their enthusiastic consumption of Carson’s records made Peer and other talking-machine company executives take notice. As country music historian Bill C. Malone notes, “Peer had greatly miscalculated the tastes of the Georgia farmers and millworkers who had been hearing Carson at fiddle contests and political rallies for many years, and he apparently failed to realize that there were millions of working-class southerners who yearned to hear music performed by entertainers much like themselves.”4

Carson also benefited from the publicity he received from Atlanta’s powerful mass media, which had made him into something of a local celebrity in the decade before his recording debut. Unlike the traditional southern musicians who preceded him on record, Carson aggressively promoted his own career by pandering to Atlanta newspapers and, more important, by performing regularly on the exciting new medium of radio. Since 1913, Carson’s much-heralded appearances at Atlanta’s annual Georgia Old-Time Fiddlers’ Conventions had been attracting extensive newspaper coverage in the city’s three major dailies, and, beginning in 1922, he garnered even greater acclaim as one of the earliest stars of Atlanta’s fledgling radio station WSB. Over the next few years, his regular broadcasts on WSB, publicized in its parent company’s Atlanta Journal, increased his popularity across Georgia and the Southeast and, indeed, throughout much of the nation. Like P. T. Barnum, Carson was a clever and relatively sophisticated self-promoter who skillfully manipulated the mass media for his own financial gain. As a consummate opportunist who was prone to recasting the facts of his life to his advantage, Carson claimed as his birthplace the hamlet of Blue Ridge in mountainous Fannin County, Georgia, and he cleverly adopted the identity of a cantankerous, free-wheeling Georgia hillbilly who distilled his own moonshine whiskey and dashed off tunes in a raucous, exuberant fashion. As old-time music historian Charles K. Wolfe has noted, Carson transformed himself into “a darling of the mass media and was written about more than any other [hillbilly recording star] from the ‘golden age’ of the 1920’s.”5

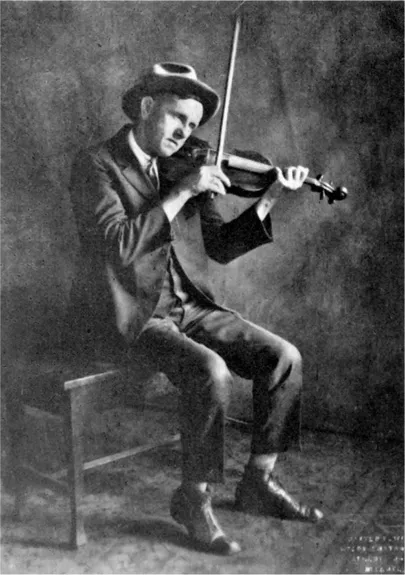

Fiddlin’ John Carson, ca. 1923. Courtesy of the Southern Folklife Collection, Wilson Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

From that historic first recording, Carson rose to become one of the most popular hillbilly radio and recording stars of the 1920s and one of the most extensively recorded artists in OKeh’s “Old Time Tunes” catalog. Billed as the “King of the Mountaineer Musicians,” he recorded more than 180 sides for the OKeh and Bluebird labels between 1923 and 1934, consisting of solo selections, duets with his daughter Rosa Lee (known on record as “Moonshine Kate”), numbers with his stringband, the Virginia Reelers, and half a dozen sides with Emmett Miller and other artists as part of “The OKeh Medicine Show.” Several of Carson’s songs, among them “The Little Old Log Cabin in the Lane,” “The Farmer Is the Man That Feeds Them All,” and “You Will Never Miss Your Mother Until She Is Gone,” are now considered early country music classics. Carson sustained his long, successful radio and recording career through constant innovation and reinvention of himself according to recording executives’ demands and consumers’ changing musical tastes. He began on record as a solo fiddler and then in 1924 recorded with stringband accompaniment. When they became popular in the late 1920s, Carson waxed nearly twenty “rural drama” skits for OKeh, with musical interludes and thin plots that revolved around the manufacture and consumption of moonshine whiskey in the north Georgia mountains. Meanwhile, throughout much of the 1920s and early 1930s, he continued to perform on Atlanta radio stations and to tour widely throughout Georgia and the Southeast until the Great Depression effectively destroyed his musical career.6

Besides his pioneering role as a hillbilly radio and recording star, Carson has attracted considerable attention from country music historians because of his unusual, archaic fiddling and vocal styles.7 Carson grew up in post–Civil War rural north Georgia, and his music, as Robert Coltman put it, is “discordant, arrhythmic, [and] idiosyncratic.” By modern standards of musical taste, he “sounds like a visitor from another world.” Carson’s biographers have typically portrayed him as coming of age isolated from the main currents of the New South’s urban life and mass culture, and his distinctive sound has encouraged country music historians to view him chiefly as a rural folk fiddler who was decidedly out of touch with early twentieth-century popular music. Unlike the overwhelming majority of hillbilly musicians who recorded before World War II, Carson was forty-nine years old, well into middle age, when he cut his first sides. Hence, his biographers believe that much of Carson’s musical style and repertoire had coalesced during the late nineteenth century, decades before he ever entered a radio or recording studio. This perception, combined with his primitive fiddling style, has prompted Carson’s biographers to treat his recordings as an extraordinary opportunity to hear the premodern folk music, once so popular at barn dances, corn shuckings, and other social gatherings in the rural South, as it was probably performed in the late nineteenth century. In his liner notes to The Old Hen Cackled and the Rooster’s Going to Crow, for example, Mark Wilson speculates that Carson’s recording of the fiddle tune “Sugar in the Gourd” “captures the sound of the country dances of the 1890s” and then asserts that his records “afford a precious glimpse of an older fiddling style native to the deep south … which had virtually died out among younger fiddlers.” Carson’s major biographer, Gene Wiggins, likewise considers him “a representative nineteenth-century folk musician.” Carson’s recordings are significant, he argues, because they offer music historians the rare privilege of eavesdropping on older, nearly forgotten southern sounds. Musically, Carson “never had changed much since he developed a style back in the 1880s,” Wiggins claims, and, thus, listening to his records offers “our best chance at hearing the sort of music many Americans liked in the 1880s.”8

Certainly, Carson must be considered a historically significant transitional figure in the early development of hillbilly music, for he was undeniably a self-taught grassroots artist who bridged the cultural worlds between the traditional folk music of the 1890s and the commercial popular music of the 1920s. And his musical education did in fact begin in the late nineteenth century. But focusing too much on this aspect of his musical evolution obscures the more decidedly modern, urban influences that shaped Carson’s hillbilly music. Even if we concede that he may never have dramatically altered his fiddling and vocal styles after 1900, Carson should not be mistakenly interpreted as an old-fashioned, untutored folk musician. Although he relied heavily upon droning, short-bow fiddling, and ornamented, melismatic singing, which seemed better suited for the country dances and minstrel shows of the late nineteenth-century rural South, his recorded songs were undeniably the product of the early twentieth-century urban South.9

Carson’s music had its origins in a dynamic rural and small-town southern world that was, already by the end of Reconstruction, deeply enmeshed in the nation’s emerging entertainment industry and mass culture. John William Carson was born on March 23, 1874, one of thirteen children, on a Cobb County, Georgia, farm about four miles north of the town of Smyrna. His father, James P. Carson, supported his wife and large family by combining cotton farming with industrial work as a section foreman on a construction crew building the Western and Atlantic Railroad. Around 1884, the Carson family resettled in nearby Marietta, a bustling market town with more than twenty-two hundred residents, some eighteen miles northwest of Atlanta. There, as a boy, John worked briefly—and carelessly—toting pails of water to the black railroad gangs building the Marietta and North Georgia Railroad. “John Carson, a waterboy with the M & NG railroad construction crew at COX Cut,” reported an 1886 newspaper, “tampered with a pistol Monday and accidentally shot himself in the leg.”10

Apparently, Carson was living in Marietta when he developed a serious interest in music. His life as a musician, he later recalled, began on his tenth birthday, when he received a fiddle—reportedly a Stradivarius reproduction dated 1714—as a gift from his paternal grandfather, Allen W. Carson, the son of Irish immigrants, who, according to his grandson, was “a powerful fiddler too.” Carson later claimed that he learned to scrape out his first fiddle tune, “Old Dan Tucker,” as he walked home from his grandfather’s nearby farm that very same day. “Nobody ever showed me anything about it,” he once boasted to an Atlanta Journal reporter. “It was just a natural gift from the Lord. I’m proud I didn’t take no lessons. They make fiddlers every day now, but I’m just a natural born fiddler.” Two years later, according to one of the many legends surrounding him, the twelve-year-old Carson’s spirited fiddling at an 1886 political rally in Copperhill, Tennessee, inspired Tennessee gubernatorial candidate Bob Taylor, himself an accomplished fiddler, to give Carson the nickname that would remain with him for the rest of his life: “Fiddlin’ John.”11

Throughout his teens and twenties, Carson mastered a large repertoire of fiddle breakdowns and traditional ballads, most of which he almost certainly learned from family members, neighbors, and other musicians in and around Marietta. But his exposure to traveling medicine shows, circuses, and especially minstrel shows, which staged seasonal appearances in Marietta and nearby north Georgia towns, also fostered his musical development. Wildly popular throughout the nation since at least the 1840s, minstrel shows featured white entertainers in blackface who performed routines of skits, dances, songs, and jokes, usually accompanied by banjo and fiddle music, in crude, exaggerated imitation of African Americans. Carson was especially attracted to the minstrel songs he heard. The first fiddle tune he claimed he ever learned to play, “Old Dan Tucker,” was a famous minstrel number written by Dan Emmett in 1843. Carson also favored “Alabama Gal,” “Old Uncle Ned,” “Gonna Raise a Ruckus,” “Turkey in the Straw,” “Dixie,” and other songs that either originated on the minstrel stage or achieved their greatest acclaim there. He later recorded more than eighteen of these minstrel songs, and although we lack specific evidence, the minstrel troupes he saw in his north Georgia youth may have inspired him to pursue a career as a professional entertainer.12

As an aspiring musician, Carson developed his fiddling skills throughout the 1880s and 1890s and earned some modest additional income by entertaining at square dances, political rallies, barbecues, and farm auctions in Marietta and the surrounding farming communities, sometimes accompanied by banjoist Land Norris and fellow fiddler Allen Sisson. At house dances, a host family would clear out the furniture in a room, roll back the rug, and invite their friends and neighbors over to an all-night square dance. A fiddler and sometimes a banjo player furnished the music, and occasionally a straw beater accentuated the rhythm by drumming broom-sedge straws, knitting needles, or wooden sticks (“fiddlesticks”) on the fiddler’s strings as he bowed them. Homemade whiskey...