![]()

CHAPTER 1: Stony Lonesome

Across the rolling plains of northern Virginia a new morning dawned. It was a soft spring day in May: bright, cool, refreshing. In the pastures cows nibbled quietly at the grass, while across the land farmers hitched up their plough horses for another day’s labor. The year was 1861.

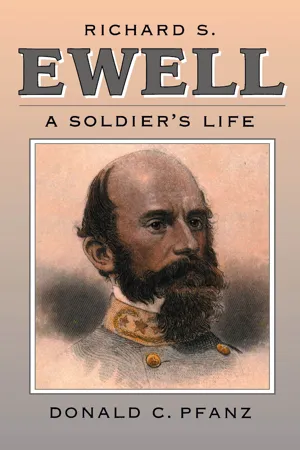

At a farmhouse ten miles west of Manassas, a forty-four-year-old man bid his brother and sister farewell and rode off to war. He carried little in the way of personal baggage, for by profession he was a soldier and accustomed to traveling light. Richard Stoddert Ewell had been an officer in the U.S. Dragoons for more than twenty years. In that time he had served primarily at frontier posts in the West, where, as he claimed, he had learned all there was to know about commanding fifty dragoons and had forgotten everything else.1 Those who knew him might have added that he was one of the army’s most competent and experienced Indian fighters.

This time, however, Dick Ewell would not be fighting Apaches but U.S. soldiers. Virginia and other Southern states had recently seceded from the Union, throwing the country into civil war. It was a prospect Ewell abhorred. Like most Regular Army officers, he felt a strong loyalty to the flag that he had long and faithfully served. His ties with the United States seemed as strong as life itself. To break them, he later wrote, “was like death to me.”2 Yet strong as was his allegiance to the national government, his allegiance to Virginia was stronger still. After painful deliberation he cast his lot with the South. Once he made the decision, he did not look back. The tocsin had sounded, and Dick Ewell, like his fore-fathers in earlier wars, could not ignore its call.

The Ewells were Virginia planters of English stock. Outside London, in Surrey County, stood an ancient Saxon village named Ewell, and there, according to tradition, the family took root.3 James Ewell left England about the time of the English Civil War and emigrated to Virginia’s eastern shore. A brickmaker by trade, James settled at Pungoteague and became a “man of substance.” He married a woman named Ann and left seven children.4

Among James Ewell’s many offspring was a boy named Charles, who became a brickmaker like his father. Charles moved across the Chesapeake Bay to Lancaster County.5 At a small inlet later known as Ewell’s Bay, he established “Monashow,” a plantation where he probably grew tobacco and other crops suited to the soil. Charles married Mary Ann Bertrand. The union produced seven children, including three boys: Charles, Bertrand, and Solomon. The youngest son, Solomon, inherited his father’s estate and went on to found the “Lancaster” branch of the Ewell family. His brothers, Charles and Bertrand, moved up the Potomac River to Prince William County and established the family’s “Prince William” line.6

Charles built “Bel Air” plantation in 1740.7 During his life he was a vestryman in the local parish and served as an officer in the Prince William militia. Charles’s wife, Sarah Ball, was a first cousin of George Washington’s mother, Mary Ball. Of the couple’s four children, three survived to maturity. Their only daughter, Mariamne, married Dr. James Craik, who became chief physician and surgeon of the Continental Army. Craik is best remembered for his close association with Washington, who referred to him in his will as “my compatriot in arms, an old and intimate friend.” When Washington died at Mount Vernon in 1799, Craik was one of three doctors at his bedside.8

Besides Mariamne, Charles Ewell had two sons who survived to maturity. Both took wives within the family. His oldest son, Jesse, married his first cousin Charlotte Ewell in 1767. Jesse’s younger brother went one better. Col. James Ewell of “Greenville” married his first cousin, Mary Ewell, and when she died, he took another first cousin, Sarah Ewell, as his second wife.

Jesse inherited Bel Air. Following the pattern of public service set by his father, Jesse served as an officer in the county militia and was a vestryman in Dettinger Parish. As a young man he attended the College of William and Mary, and while there, he became a close friend of his Albemarle County classmate Thomas Jefferson. The two men remained friends until Jesse’s death in 1805. They corresponded frequently, and Jesse occasionally hosted Jefferson at his home. During the Revolution, Jesse was a colonel in the militia, though his regiment apparently never saw combat. His silver-hiked rapier was later given to his grandson Richard Ewell, who wore it during the final years of the Civil War.9

The marriage of Jesse and Charlotte Ewell resulted in no fewer than seventeen children. One daughter, Fanny, married the Reverend Mason Locke Weems, the author of a popular early biography of Washington. “Parson” Weems’s stories of young Washington cutting down the cherry tree and throwing a coin across the Rappahannock, though probably fictional, have long been part of American lore.10

Col. Jesse Ewell of Bel Air (Alice M. Ewell, Virginia Scene)

The hilt of Col. Jesse Ewell’s sword from the American Revolution. General Ewell wore the sword during the last half of the Civil War. (Judge John Ewell)

Bel Air, the home of Col Jesse Ewell (Donald C. Pfanz)

Fanny’s younger brother Thomas, born in 1785, was Charlotte Ewell’s fourteenth child.11 Thomas had a brilliant but erratic mind and a fiery, restless disposition. As a young man he studied medicine under Dr. Benjamin Rush at the University of Pennsylvania. Following his graduation in 1805, Thomas received an appointment as a surgeon in the U.S. Navy through the influence of his father’s friend Thomas Jefferson. He served first at New York City’s naval yard and later at Washington, D.C.12

For Thomas medicine was more than a profession; it was a challenge. A daughter recalled that he “disliked the practise of medicine, unless the case was an exciting one, such as to call out all his powers of analysis in the symptoms and cause of disease, and the discovery of new and better modes of treatment.” His quest for knowledge sometimes got him into trouble. On one occasion he was nearly mobbed by an angry crowd for dissecting the brain of a deceased patient without the consent of the man’s widow.13

Thomas published the results of his investigations in five books spanning almost two decades. Some of his theories were far ahead of their time. In his book Discourses on Modern Chemistry, for instance, he promoted the use of chemical fertilizers, soil testing, and insect control to increase crop yield and advocated conservation techniques to prevent the destruction of American forests. Some of his ideas spawned controversy within the medical community. His book Letters to Ladies, remembered one descendant, “shocked the ‘delicate and refined females’ of that day by attributing their fainting fits, tears, and tantrums to illness of body and not to sensibility of soul.” Pre-Victorian America was not yet ready to accept such progressive thinking.14

Only once did Thomas Ewell make a literary venture outside the field of science. That occurred in 1817 when he edited the first American edition of philosopher David Hume’s Essays. Like everything to which Thomas Ewell set his hand, the book inspired controversy. The Catholic and Episcopal Churches had proscribed Hume’s books, and Ewell was publicly censured for publishing them. The doctor was unrepentant. Although a devout Episcopalian, he found Hume instructive and believed the general public, like himself, could read books and extract what was valuable “without being affected by the dross contained in them.”15

On 3 March 1807 Thomas married Elizabeth Stoddert in Georgetown. James and Dolley Madison attended the ceremony. In 1808 Elizabeth delivered a daughter, whom she named Rebecca Lowndes in honor of her mother. Other births followed: Benjamin Stoddert in 1810, Paul Hamilton in 1812, and Elizabeth Stoddert in 1813. A fifth child died in childbirth, but by the summer of 1816 Elizabeth was again pregnant. On 8 February 1817 she gave birth to her third son, a boy whom she named Richard Stoddert after a deceased brother.16

Richard first saw light at his mother’s childhood home, “Halcyon House,” at the southwest corner of Thirty-fourth Street and Prospect Avenue in Georgetown. Built by Elizabeth’s father in 1785, the large brick building, with its rolling terraces and panoramic view of the Potomac River, was one of the oldest and grandest houses in town. Wrote one historian, “No site could have been fairer and the house, as Major Stoddert built it, was worthy of the site.”17

Richard retained no memories of his birthplace. When he was just one year old, his family moved to Philadelphia, where his father attended a series of medical lectures at the University of Pennsylvania. The Ewells returned to the District of Columbia in 1819 and moved into a new two-story brick house on the west side of President’s Square across from the White House. At that time Washington was still sparsely populated, and only two other buildings stood on the block: St. John’s Church and Commodore Stephen Decatur’s house. Decatur was mortally wounded in a duel with Commodore Barron a short time after the Ewells’ arrival. The Ewell children watched as his near-lifeless body was carried back to his house.18

Halcyon House, the Georgetown home of Benjamin Stoddert and the birthplace of General Ewell (Library of Congress)

The Ewells had been in Washington just one year when Thomas’s health began to fail. Apparently the doctor’s brilliance and eccentricity had led to excess. He became an alcoholic and suffered bouts of depression. The fortune he had amassed dwindled, and his successful medical practice languished.19 In 1820 the Ewells left Washington and moved to “Belleville,” a 1,300-acre farm in Prince William County, Virginia. Because of its rocky soil and isolated location, family members took to calling the property “Stony Lonesome,” a name that stuck.20 In addition to Stony Lonesome, the Ewells owned four one-half-acre lots and a large house in Centreville, Virginia, called “Four Chimney House.”21 They continued to retain possession of their Washington home, which they rented to top government officials for as much as $600 a year.22

Four Chimney House in Centreville, Virginia, once owned by the Ewell family (Library of Congress)

The Ewells were slaveholders. Census records for 1830 show two black females living at the house.23 One of these was Fanny Brown, better known to the family as Mammy. Fanny was not actually a slave. She had been acquired as chattel by Benjamin Stoddert, but Thomas Ewell later freed her from bondage after she successfully nursed him through a dangerous fever. Fanny accompanied the Ewells to Stony Lonesome, where she managed the poultry, did the cooking, and performed other routine chores around the house. To the children she was both a comforter and adviser, and they loved her like a mother. No one dared take liberties with Fanny, however, not even Mrs. Ewell. More than once, when Elizabeth rebuked her or offered some unintentional slight, Fanny packed her bags and walked out the door. But she never made it past the front gate. Moved by the tears of the Ewell children, who followed her weeping to the road, she always changed her mind and came back—“just to spite Mistis,” she claimed.24

Two servants, three houses, and an abundance of land gave the family an aura of wealth that it did not possess. Like many Virginians the Ewells were land poor; that is, they owned large amou...