eBook - ePub

A Communion of Shadows

Religion and Photography in Nineteenth-Century America

- 312 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

When the revolutionary technology of photography erupted in American culture in 1839, it swiftly became, in the day’s parlance, a “mania.” This richly illustrated book positions vernacular photography at the center of the study of nineteenth-century American religious life. As an empirical tool, photography captured many of the signal scenes of American life, from the gold rush to the bloody battlefields of the Civil War. But photographs did not simply display neutral records of people, places, and things; rather, commonplace photographs became inscribed with spiritual meaning, disclosing, not merely signifying, a power that lay beyond.

Rachel McBride Lindsey demonstrates that what people beheld when they looked at a photograph had as much to do with what lay outside the frame — theological expectations, for example — as with what the camera had recorded. Whether studio portraits tucked into Bibles, postmortem portraits with locks of hair attached, “spirit” photography, stereographs of the Holy Land, or magic lanterns used in biblical instruction, photographs were curated, beheld, displayed, and valued as physical artifacts that functioned both as relics and as icons of religious practice. Lindsey’s interpretation of “vernacular” as an analytic introduces a way to consider anew the cultural, social, and material reach of religion.

A multimedia collaboration with MAVCOR—Center for the Study of Material & Visual Cultures of Religion—at Yale University.

Rachel McBride Lindsey demonstrates that what people beheld when they looked at a photograph had as much to do with what lay outside the frame — theological expectations, for example — as with what the camera had recorded. Whether studio portraits tucked into Bibles, postmortem portraits with locks of hair attached, “spirit” photography, stereographs of the Holy Land, or magic lanterns used in biblical instruction, photographs were curated, beheld, displayed, and valued as physical artifacts that functioned both as relics and as icons of religious practice. Lindsey’s interpretation of “vernacular” as an analytic introduces a way to consider anew the cultural, social, and material reach of religion.

A multimedia collaboration with MAVCOR—Center for the Study of Material & Visual Cultures of Religion—at Yale University.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access A Communion of Shadows by Rachel McBride Lindsey in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Theology & Religion & North American History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

ONE

WHEN I AWAKE WITH THY LIKENESS

Sometime after James Nash and Mary Sheldon were married at Minersville, Pennsylvania, on July 4, 1868, they purchased a full-gilt New Illustrated Devotional and Practical Polyglot Family Bible in luxurious Turkey morocco binding. By the time they bought their Bible, most likely from a canvassing book agent who would have assured them that the binding was the only option for “persons who want a magnificent Bible,” the Nashes had moved seventy miles north from Schuylkill County to Lackawanna Township and had welcomed the birth of their first daughter, Annie. Like most other men in the largely immigrant neighborhood, James was working in the coal mines while Mary was at home with Annie, likely already expecting the arrival of their second child, Elizabeth, who was born in February 1872. Whatever the precise date of purchase, the event marked not only an investment in a sacred text but also a material declaration of the Nash family—the Bible, in other words, was intended not only as scripture but as a lasting testament of James and Mary’s legacy.1

For a family of three or more on a miner’s paycheck, the Bible’s purchase price of between $9 and $13 well exceeded the cost of other options—for instance, the similarly sized (101/2 by 13 inches) roan-bound “Pica Bible,” with references, published by the American Bible Society and sold for $3—and thus established the investment as a desire for something more than a copy of the scriptures.2 In addition to whatever value the Nashes attached to the sacred text concealed beneath the heavy raised panels of the leather binding, the Bible was a cultural space that not only signified devotional practice but also established through specific gestures—purchase, display, transcription, accumulation—historical presence, a presence that was signaled before one even opened the cover of the enormous leather-bound compendium of sacred knowledge, elegantly embossed with gilt decorative work and James’s initials and that lasted long after the family’s corporeal demise. This family was here, it declared. And here is their story.

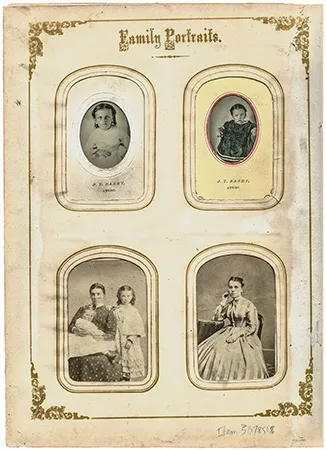

Signaling historical fortitude and inviting those who would finger the enormous volume to reflect not only on its scriptural content but also on the family whose story it told, the Nashes’ Bible was not unlike other family Bibles popularized after the American Civil War. In addition to the biblical text, for instance, its contents featured “A history of the religious denominations of the world,” many “valuable treatises,” including a “History of the Translation of the Bible,” and a host of “Chronological and Other Useful Tables, Designed to Promote and Facilitate the study of the Sacred Scriptures.” Among the latter was “A Table of Kindred and Affinity: Forbidden to Marry Together,” buried in the back pages and evidently included to clarify appropriate nineteenth-century familial relations.3 Along with the written material, moreover, the Bible included a number of maps of the Holy Land and was “Embellished with Over 200 Fine Scripture Illustrations.” In pages strategically positioned between the Old and New Testaments and continuing the practice of generations of Americans before them, moreover, the Nashes dutifully recorded their matrimony and the births of their ten children over the next two decades (as well as the deaths of four) in the printed registries provided by the publisher, thus positioning their own family history within a biblical chronology.4 Unlike previous generations of recording practices, however, the Nashes’ Bible also included a “Photographic Album for Sixteen Portraits” (fig. 4).

Introduced in the early 1860s, when card-size carte de visite prints became an immensely popular social currency, family photograph albums within family Bibles typically consisted of two leaves with four apertures on each facing page.5 Among the family portraits preserved in the Nashes’ sanctified album were twelve such mounted calling card–size prints, as well as four tintypes taken by “J. Y. Barry, Artist.” Although placed at the end of the volume rather than between the Testaments, these visual genealogies shared with their textual counterparts the simultaneous effect of recording the ordinary course of the Nash family’s lives and positioning their lineage within a sacred chronology that was guided less by the accidents of history than by the masterful plan of the album’s Creator. Throughout the latter half of the nineteenth century, family Bible portrait galleries brought communities of saints past, present, and future into a communion of shadows.

Few Americans committed their encounters with family Bibles to writing. In her 1929 memoir, Anne Ellis was an exception. The “ordinary woman” recalled that her childhood “big family Bible . . . had designs all around the leaves, places for photographs, also places for births, deaths and marriages.” “It must have been made to sell, certainly not . . . to be read,” Ellis conjectured, but she remembers specific episodes in her girlhood associated with the massive book—her Mama and the biblical Rachel “weeping for [their] children,” her brother Frank hiding a nickel between the leaves and then cutting them out with a knife in his effort to rescue the coin, finding flowers from “Mama’s old home” and “from a dead baby’s coffin” tucked between its leaves, the latter twined with a lock of hair. But in contrast to these vivid memories of the Bible, Ellis is silent on whether or how her mother placed photographs in the designated pages. Much like Ellis, cultural memory has forgotten about the photographs.6 Throughout the latter half of the nineteenth century, Bibles and photographic portraiture were commonly associated in material form and in display practices that linked individual likenesses with broader narratives of family, race, and sacred history. When placed within the pages of the Bible, I argue, photographic portraiture’s long-acknowledged contribution to constructions of race and nation were accompanied by an equally significant visual reckoning of the soul.

Figure 4. Nash Bible “Family Portraits” album page, New Illustrated Devotional and Practical Polyglot Family Bible (Philadelphia, 1870). Princeton University Library. Used with permission.

When asked by his precocious nephew, Tom, about the origins of “the art of photography” in 1879, an essayist in the British youth magazine Little Gleaner responded with a tidy history of the medium’s nineteenth-century “discovery” and development. When he concluded that its success was evident in the fact that “there is scarcely a house in the kingdom, from the royal palace to the humblest cottage, but possesses some specimen of photography,” Tom mused in wonderment at the possibility of gathering “all those photographs together”: “what a monstrous album would be required for them!” Evidently an eager pedagogue, Tom’s uncle responded with the observation that “it occurs to me I have seen such an [sic] one as you suggest.” To his nephew’s mirthful skepticism, the essayist continued: “Nay, lad, I am serious. Do you not think most people possess a Bible? and is it not comparable to an album? for it contains portraits drawn by God, who is essential light; and, as proof of its magnitude, there is not a person in the world but what, if they had the seeing eye, might discover themselves in it.” More than a record of ancient lives, the Bible, through God’s “essential light,” was continuously augmented with the likenesses of the generations: “By carefully looking over the blessed book we have been talking of, discover your portrait, for it abounds with precious likenesses which will shine like jewels in your eyes if you can but get a proper light thrown upon them by the Holy Spirit being your Guide.”7

If Tom’s uncle was using the common portrait album as an allegory for the volume of “precious likenesses” of the ancients, he was nevertheless writing at a time when portrait albums had been part of the physical arrangement of family Bibles for nearly two decades in both Britain and America. Hardly an isolated association, moreover, his lesson echoed a then-familiar mode of identification between albums and Bibles. In his early social history of photography, published in 1938, Robert Taft recounts pioneer reminiscences of a flour barrel, domesticated by a white lace coverlet, “whereupon reposed the family Bible and photograph album.” Taft uses this anecdotal evidence to elevate the status of the common enough family album to a level on par with that of the equally ubiquitous family Bible. Decades later, cultural historian Martha Langford observed that “if the album tore a page from the family Bible, it was the ‘family record.’” While her observation registers a degree of collaboration between visual and transcribed records, Langford nevertheless positions albums as biblical replacements rather than as contemporary counterarchives. But albums and Bibles mirrored each other in a variety of ways, reflecting back on each other both their physical form and ideological legacies, among them the racialized construction of family heritage. Such mirrorings notwithstanding, likenesses within family Bibles further entangled these ideational chords with a biblical narrative that purposefully dismissed the pesky constraints of historical time.8

Although historians of photography have made interpretive correlations between albums and Bibles in order to augment albums’ cultural authority and historians of religion have recognized the visual history of family Bibles, the study of photographic studio portraiture within family Bibles raises new questions about religion in nineteenth-century American culture. Paul Gutjahr and Colleen McDannell have each noted the existence of these galleries in passing, but within the broader sweep of the communion of shadows we learn something from a longer look.9 To this end, this chapter builds out from existing scholarship to chart an interpretive history of family Bible portrait albums, a practice that began shortly after 1860 and continued through the end of the century. During this period, at least twenty-five Bible publishers with locations in more than fifteen cities—primarily in New York, Philadelphia, and Boston, long-established hubs of Bible publication in the United States—provided family Bibles that included pages for “family portraits” or “family galleries.”10 Placed almost uniformly at the end of the binding, these galleries appeared in Bibles of both Authorized and Douay-Rheims translations and, after 1881, in “combination” editions that provided parallel columns of both Authorized and Revised translation.11 Despite the augmentation of materials included in family Bibles over this period, and in particular the heightened use of chromolithography and “illuminated” engravings of biblical events and figures based on the works of popular contemporaries Gustave Doré and Heinrich Hofmann, moreover, the photographic leaves remained remarkably consistent over the course of four decades. Variations of page ornamentation on photograph leaves occurred, but by and large publishers included space for between thirteen and seventeen portraits in roughly the same format: four rectangular die-cut openings per side of two leaves of heavy stock or, after 1866 when the larger “cabinet card” portrait was introduced, a space for this larger photograph at the beginning of the album section followed by three or four pages of the smaller apertures.12

Both their shared physical characteristics with albums and the visual habits informed by portraiture convention conditioned the interpretive possibilities of Bible portraiture. Photographic historians have established a number of conventions for dividing portrait photographs into various classifications that supposedly evoked differing visual strategies. Anna Pegler-Gordon, for instance, has identified one such binary as “the honorific self-presentation of bourgeois subjects” and the “repressive representation of prisoners, patients, and the poor.”13 Shawn Michelle Smith makes a similar distinction between “scientific and criminological mug shots,” on the one hand, and “middle-class portraits,” on the other.14 Barbara McCandless has taken a different approach, identifying the two modes in which to categorize early photographic portraiture as the “democratic” appeal of making affordable likenesses of family and friends and the “morally instructive” practice of beholding “images of society’s leaders.”15 While helpful to map the visual culture of photographic portraiture, that is, the different ways in which portraits were approached and interpreted, these distinctions also risk obscuring the ways in which affordable likenesses of family and friends, made according to established conventions of representation, could be at the same time morally instructive, racially informed, and ideologically charged in ways that did not necessarily map onto the intentions of photographers, scientists, or state officials. In other words, such interpretive compartmentalizations of photographic portraiture privilege the intent of an authorized gaze according to aesthetic convention rather than the tangle of visual habits that could prompt any number of interpretations of a particular likeness.

Moreover, these existing classifications typically assume that photographic portraits were always made to document the present. As historian Martha Sandweiss advances in her study of photography in the American West, however, from an early period, photographs “were invested with the power of myth and cloaked in the gauzy haze of nostalgia; they evoked a longing for the past rather than an understanding of the present.”16 Sandweiss is here considering the ironic use of staged cowboy photographs as “straightforward reportage” in subsequent histories of the American West, but her attention to the ambiguous temporal positioning of photographic portraiture speaks to the unstable—indeed, the mischievous—operation of time in photograph albums as well. More than a document of a particular moment, photographic portraits brokered an imagined past with an anticipated future through a selective present. It was in this unstable encounter between beholder and likeness, between an embodied present, an imagined past, and an anticipated future, that Bible portrait galleries were firmly positioned within the charged chronography of sacred time.

Photograph albums were ordinary objects where beholders were instructed and inspired by the likenesses of friends and family no less than those of greater fame. Even outside of the charged archival context of the family Bible, the physical arrangement of albums was believed to inspire personal reform in anticipation of celestial reunion, as demonstrated in a placard inserted into an early album of card portraits that waxed in verse how communion with these familiar shadows prompted beholders toward “the home . . . beyond the sky”:

This book contains much choicer gems

Than any casket on the earth,

It holds the Portraits of our friends,—

Some who have known us from our birth;

. . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Memory of such we’d always have,

But, haply, some who’re here portrayed,

Have left the changing scenes of time,

To dwell among a holier throng,

To labor in a happier clime.

The thoughts of those thus brought to mind

Shall raise our aspirations high,—

Shall help us on to seek the home,

That they have found beyond the sky.17

The relationship among visual habits of the present, memories of the past, and aspirations toward the future the poem articulates can be mapped onto contemporary photographic discourse in a way that emphasizes the ideological and indeed theological roles of photographic portraiture without assuming a causal relationship between aesthetic convention and a photograph’s meaning for its beholders. And whether the card was tucked into a photograph album or a Bible gallery, its sentiment underlined a viewing habit common to both archives, namely, that beholding the likenesses of friends and family carried the aspirational potential that parallels the shadows of more famous folk. In short, in these verses we behold a silhouette of a much deeper communion of shadows.

Using family Bible portrait galleries as a point of entry into the communion of shadows, in this chapter I unravel the a...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Figures

- Acknowledgments

- A Note on the Images

- Introduction: A New Testament

- 1: When I Awake with Thy Likeness

- 2: Here Is My Name When I Am Dead

- 3: Agents of a Fuller Revelation

- 4: By Pencil and Camera

- 5: Beyond the Sense Horizon

- Epilogue: How Mr. Eastman Changed the Face of American Religion

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index