- 248 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Seeing Race in Modern America

About this book

In this fiercely urgent book, Matthew Pratt Guterl focuses on how and why we come to see race in very particular ways. What does it mean to see someone as a color? As racially mixed or ethnically ambiguous? What history makes such things possible? Drawing creatively from advertisements, YouTube videos, and everything in between, Guterl redirects our understanding of racial sight away from the dominant categories of color — away from brown and yellow and black and white — and instead insists that we confront the visual practices that make those same categories seem so irrefutably important.

Zooming out for the bigger picture, Guterl illuminates the long history of the practice of seeing — and believing in — race, and reveals that our troublesome faith in the details discerned by the discriminating glance is widespread and very popular. In so doing, he upends the possibility of a postracial society by revealing how deeply race is embedded in our culture, with implications that are often matters of life and death.

Zooming out for the bigger picture, Guterl illuminates the long history of the practice of seeing — and believing in — race, and reveals that our troublesome faith in the details discerned by the discriminating glance is widespread and very popular. In so doing, he upends the possibility of a postracial society by revealing how deeply race is embedded in our culture, with implications that are often matters of life and death.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Seeing Race in Modern America by Matthew Pratt Guterl in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & North American History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART I

Close-Ups

The Devil in the Details

I have blond hair, blue eyes, and fair skin. My brother however

is the exact opposite. Basically what I’m asking is if someone who

has blond hair and blue eyes and fair skin, if they were to tan and

get dark and dye there hair black would they look Mexican[?]

“WHAT MAKES A MEXICAN LOOK LIKE A MEXICAN?,” YAHOO ANSWERS

is the exact opposite. Basically what I’m asking is if someone who

has blond hair and blue eyes and fair skin, if they were to tan and

get dark and dye there hair black would they look Mexican[?]

“WHAT MAKES A MEXICAN LOOK LIKE A MEXICAN?,” YAHOO ANSWERS

When an anonymous young woman posted her question on Yahoo—“What makes a Mexican look like a Mexican?”—she asked for “serious and kind answers only.” “You know,” she explained, “when you look at a person, and automatically know that they are most likely Mexican, not by the way they dress or language there [sic] talking, but there [sic] characteristics like dark hair, dark skin, etc?”1 Her request for thoughtful responses didn’t stop one respondent from suggesting that she look for “a really big Sombrero.” She also got a long answer describing the mix of peoples and races that went into the Olmec civilizations, a response with three links to a flickr account corresponding to the three racial types supposedly found in Mexico, and still another from someone who began by noting that “many Mexicans do have black or dark brown hair, brown eyes and dark skin” before continuing on to say that “I had a neighbor who was Mexican as well, with blonde hair and green eyes. Her skin was lighter than mine. I didn’t believe her until she held her arm next to mine—and I’m not dark-skinned at all.” Still, despite the anecdotal diversity, the author of the post was satisfied enough with their collective confirmation that the right answer was written on the body somewhere to mark the question as “resolved.”

Here, I want to explore the workings of three sightlines—those related to racial profiling, to silhouetting, and to racial commodification. I do so without, by and large, a straightforward chronological orientation because I am interested in a specific way of seeing. All three of these examples, I argue, depend on very close readings of the familiar racialized body alone, typically without ensemble and accompaniment, emphasizing the sorts of minutiae critically engaged by racial sight. All three are thus illustrative of the sorts of close readings done regularly, in these and other parallel sightlines, and in any focused consideration of the single body, where microscopic detail is mined from the singular, racialized physique for proof of origins.

These close readings present themselves as unconscious, or instinctual, and not as manifestations of a specific, practiced technique. On an episode of Identity, a now defunct game show on NBC hosted by comedian Penn Jillette in 2006 and 2007, a contestant surveyed the body of “person No. 8.” The premise of the show was that contestants would look over the body of a different person each week and rely on their instincts to make snap judgments about the character, personality, and identity of the numbered person before them. On this particular episode, “No. 8” was wearing very little—only a black bikini top, denim shorts, and a jeweled halter collar. She stood alone on the stage, waiting for her identification. With heightened gravitas, Jillette asked the female contestant, “Is she Haitian?” For a minute, against the stressful background of dramatic music, the woman nervously surveyed the body and face of No. 8. At one point, she complained that No. 8 didn’t look like “the textbooks [she’d] read.” Finally, she guessed: “Yes, I think she is.” “Well, I live in LA,” No. 8 replied blithely, “but I was born in Haiti.” The crowd cheered.

Like the young woman seeking to know what it means to look “Mexican,” Identity capitalized on the craze for subconscious, unprocessed visual interpretation—epitomized by the publication of Malcolm Gladwell’s Blink in 2005. But in this episode, and in others, Identity also depended on a kind of encyclopedic, collective memory about race, and encouraged the supposedly careful scrutiny of the face and the body to find and interpret a curl of hair, or shade of skin color, or shape of a chin to mark one as “Haitian” and not, say, “Jamaican.” Or to see Haiti as an imprecise synonym for “black.” This dependence and its particular manifestation here—seeing “Haiti” in No. 8—suggests, in the end, that racial sight isn’t truly instinctual, and that human beings aren’t driven by nature to search for these markings, but that these distinctions emerge to serve and are given greater meaning by recent historical context. In the modern age, they have been formed and structured by the modern institutions of slavery and empire, nationalism and internationalism, among others. As ways of looking, they are constituted by—and in turn constitute—other structures of power, other manifestations of difference.

The complete cataloging of No. 8 is one example of something we do every day—something we don’t often think about or analyze carefully. We narrowly focus on what we assume is self-evident and obvious: the skin color divide between black and white. We set aside the smaller, easily synthesized “facts” that make that narrower focus possible. And in doing so, we utterly fail to properly understand exactly how race gets seen, how it is made, and how it has changed—and not changed—over time. The seeing of No. 8, then, is not the just the story of social construction of color; it is also the story of the eye in context, schooled to see the same thing in the face and on the body, to see a panoply of overdetermined details, brimming with public importance. The contestant didn’t merely see what she thought was black skin; she also saw other subcutaneous specifics. And the audience’s applause was confirmation that she attended to what was imagined as the right details, and reached what was seen as a logical conclusion.

A critique of the discriminating look should have, at the very beginning, a discussion of the body without relation, of the body alone, on a dais and under a spotlight, like No. 8. Unattached bodies like that of No. 8 are viewed outside of an ensemble or partnership, and thus require different techniques of sight. But they are still very easily seen within the racial landscape—more easily seen, for example, than the passing figure, or the ambiguous physique, both of which I will consider later. These singular, easily discerned bodies become, for instance, fixtures of state policy through racial profiling and other criminal and anti-terror initiatives. Or they become silhouettes whose certain edges present themselves as “obvious,” defying debate. Or they become biopolitical metaphors for consumer goods and for the dazzling world of services and servants. Their most important shared quality, however, is that they are seen primarily alone, without relation or juxtaposition or comparison, and that their proper identification is determined by the structured body, by the slope of the brow, by the flare of the nose, by the length of the fingers and the shape of the lips, by the shape of the breast, or by the texture of the hair. Absent larger comparison and contrast, the devil is in the very finest details.

CHAPTER ONE

Profiles

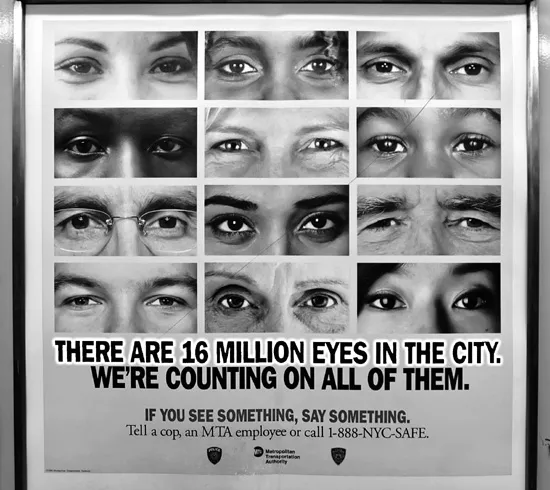

“There are 16 million eyes in the city,” the poster reads, “[and] we’re counting on all of them.” An array of twelve sets of eyes, each marked with racial and ethnic distinctions, stares outward at the reader. A part of the “See Something, Say Something” sloganeering effort of the Metropolitan Transportation Agency in New York City, the poster was framed by stainless steel and encased in one of the official protective frames found on most of the city’s subway trains. The MTA’s use of this imperative axiom was a by-product of the attacks on September 11, 2001, and the image on the poster conveyed what was a standard response of the cosmopolitan metropolis to the threat posed by global terrorism. The array of different faces and eyes communicated a common cause, with the larger, polyglot group self-interestedly guarding a generally shared and collected interests. The thing to be seen was, of course, the “terrorist,” inevitably construed as brown, as Arab, and as Muslim. The entire city, MTA spokesman Kevin Ortiz remarked, would be “the eyes and ears of our system.”1 Establishing a commonplace practice of racial profiling by a multicultural community, the image offered up a militarized world city, populated by myriad and discrete racial types, searching for those who were easily identifiable, and who would destroy the uniform fabric of twenty-first-century America.

By the spring of 2010, “See Something, Say Something” had become a national campaign. Dan Fanelli, an insurgent Republican candidate for a seat in the House of Representatives, asked television viewers in central Florida to trust their eyes. In the commercial, he stood between an elderly man presented as “white,” with light skin, white hair, glasses, and a tie, and a younger, muscled man with dark hair, wearing a black t-shirt, with a scowl and a menacing, hunched-over posture. Fanelli gestured to the bespectacled white face and, with heavy sarcasm, asked his potential constituents, “Does this look like a terrorist?” Laughingly, he then turned to “this guy”—the man we are meant to see as dark, as foreign, as Islamic—and asked the same question. Railing against “political correctness” and speaking over the theme music from the classic 1971 “tough cop” film Dirty Harry, the would-be congressman suggested that racial profiling was a necessarily logical antiterrorism strategy, and that, by forsaking it, the nation-state was making a critical mistake that would cost lives. People from the Middle East could be more closely watched, he told the Washington Post, because “you can’t be light and from those countries.” Linking race to place, and skin color to climate and geopolitical location, Fanelli’s “common sense” split apart those who “look like” Americans from those who “look like” they could be terrorists, a division that made sense only if one agreed that “an Arab” was a singular thing, identifiable with a brief look.2 Later that week, comedian Jon Stewart, poking fun at the presumption of the look on his Comedy Central “news” show, reversed the valance, and wondered if the older, lighter man was “Dr. Kevorkian,” the much-maligned proponent of assisted suicide, and if the younger, darker man was a comparatively harmless, well-suntanned “Guido” cast member from the reality television show The Jersey Shore.

The public eye, as conceived by the “See Something, Say Something” campaign, here broadcast on a subway. David Goehring/Flickr/Creative Commons.

The obvious Arab, otherwise known as “this guy,” from Dan Fanelli’s campaign commercial.

Fanelli’s campaign, likewise, assumed that viewers would see things through a common logic, without explanation or interpretation. The MTA poster—and the campaign it reflected—suggested that common cause, especially in the service of the nation-state, could produce common sight, that shared vision could conjure up a single enemy, and that the single enemy could be identified, by those dozen uncommon eyes, as a verifiable racial and religious type. Both confirmed the practice of establishing a common sight around the relation of race and crime (commonly called racial profiling, but now a feature of antiterrorism campaigns) that has long been one of the most prominent sightlines in contemporary American political culture. “See Something, Say Something” was not merely a slogan but also a call to articulate the specifics of race as a part of shared public policing of bodies marked as brown, or Arab, or Muslim.

Before 9/11, the concept of racial profiling had been most closely associated with domestic concerns: the overpolicing of African Americans in the 1980s and 1990s, or the intense surveillance of Central American gangs in the broader American Southwest. A feature of the American racial landscape for two generations, and a component of the “broken windows” theory of urban policing, the tactic’s foundational assumption was that attention to little things could make a big difference, or that a black man out of place—in a white neighborhood, driving an expensive car, or entering an exclusive boutique—was quite likely in the midst of making trouble. The “common sense” of the practice was, then, a matter of assigning a criminal identity based on surface physical characteristics and performative markers that were easily racialized and historicized. Fanelli’s commitment to that discriminating look was, in the wake of 9/11, standard-issue, hard-right boilerplate, applicable to myriad social concerns, many of them outside of major cities. It was as common with Republicans as with many conservative Democrats, all of whom were interested in firming up the border between the United States and Mexico, in seeming tough on national security, or in preventing the ingress of radicals and terrorists and “illegals.” As Arizona congressional candidate Gabriella Saucedo Mercer put it, most of the world’s dangerous populations “look Mexican, or they look like a lot of people from South America—dark hair, brown eyes. And they mix.”3

With its tactical emphasis on bodies out of place—in the wrong neighborhood, driving the wrong car, or in the wrong store—racial profiling has a stark geographic quality, an emphasis on ideal, racially ordered space. In an age of widening socioeconomic divergence for everyone, its emphasis on race, and not class, seems quintessentially American, reflecting the way that diminishing chances for poor white progress get translated into shared white concern about the spatial transgressions of people of color. Contrarily, with its reliance on surveillance and authoritarian action, racial profiling would also seem to be a desperate creation of the supposedly un-American tropics, a reflex of effete colonial powers and juntas, anxious to retain control, turning loose the police function of the nation-state. In these iterations and others, the first assumption of racial profiling is that we know race. That we, as a social body, can see race well enough, clearly enough, and intelligently enough to make an assessment about who is most certainly a criminal and who is most certainly not. What interests me about racial profiling, then, is not its political function but its social function, not its claims to be a part of “good policing” but its older, less understood role as a way to see the foreign body in contrast with the ideal social body.

That first assumption—that we can police what we see—isn’t new, and it deserves a history of its own. In 1854, the Mobile, Alabama, physician Josiah C. Nott and the former U.S. Consul in Cairo, George Glidden, published a massive ethnological survey, Types of Mankind. The work was nominally derived from the craniometric examinations conducted by the recently deceased Samuel George Morton, a renowned figure in American ethnology, and the man who, as Ann Fabian puts it, “defined” scientific racism.4 It drew deeply from Morton’s own conclusions to show that racial differences were profoundly speciated—that is, that skin color and other physical and mental indicators of difference marked the borders of distinct species, or “types.” To make this point clear, Nott and Glidden included a foldout array of the world’s various racial ty...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Seeing Race In Modern America

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- PART I Close-Ups

- PART II Group Portraits

- PART III Multiple Exposures

- Coda

- Notes

- Index