- 400 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

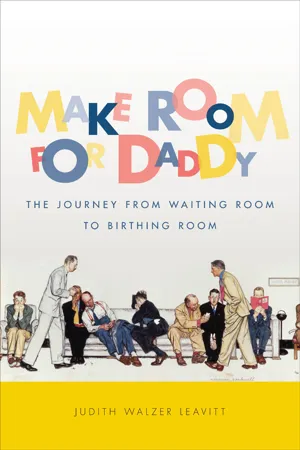

About this book

Using fathers' first-hand accounts from letters, journals, and personal interviews along with hospital records and medical literature, Judith Walzer Leavitt offers a new perspective on the changing role of expectant fathers from the 1940s to the 1980s. She shows how, as men moved first from the hospital waiting room to the labor room in the 1960s, and then on to the delivery and birthing rooms in the 1970s and 1980s, they became progressively more involved in the birth experience and their influence over events expanded. With careful attention to power and privilege, Leavitt charts not only the increasing involvement of fathers, but also medical inequalities, the impact of race and class, and the evolution of hospital policies. Illustrated with more than seventy images from TV, films, and magazines, this book provides important new insights into childbirth in modern America, even as it reminds readers of their own experiences.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Make Room for Daddy by Judith Walzer Leavitt in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Medicine & Medical Theory, Practice & Reference. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1*

ALONE AMONG STRANGERS

The Medicalization of Childbirth

The vast majority of American women (99 percent) currently deliver their babies in hospitals, accompanied by their physicians, nurses, and midwives and often by their husbands, partners, family, and friends. The hospital routine is fairly standard, although variations exist among hospitals, and medical protocols have been developed for most exigencies. Many women discuss the possible procedures in advance with their physicians and midwives and, within prescribed limits, make birth plans outlining their choices about what might happen to them during labor and delivery. Once labor begins, however, some women find that their desires are ignored, either because a different physician happens to be on call or because the course of their labor necessitates unexpected specific interventions. Because of the need for medical assessment on the spot, often more decisions are left to the hospital and the physician than to the woman or her family.1

This kind of “medicalized” childbirth is relatively new, a product of the twentieth century. Even though we have come to accept it as typical, the historical record is very clear on how recent a phenomenon it is for physicians to be in control of labor and delivery and for women to bow to their expertise. Before settling in with the fathers for the rest of the book, this chapter reviews the broad trends in American childbirth and examines how and why and under what conditions such hospital-based, physician-directed, medicalized childbirth evolved. In the process, it lays out why mid-twentieth-century birthing women came to want their husbands to accompany them through labor and delivery in the hospital.

Traditional Childbirth

For most of human history, childbirth was exclusively a woman’s event. When a woman went into labor, she “called her women together” and left her husband and other male family members outside. “I went to bed about 10 o’clock,” wrote William Byrd of Virginia in the eighteenth century, “and left the women full of expectation with my wife.”2 Only in cases in which women were not available did men participate in labor and delivery, and only in cases in which labor did not progress normally did physicians intervene and perhaps extricate a dead fetus. A midwife orchestrated the events of labor and delivery, and women neighbors and relatives comforted and shared advice with the parturient.

Ebenezer Parkman wrote in the middle of the eighteenth century of one of the twelve times his wife was “brought to bed”: “My wife very full of pain. This Morning I sent Ebenezer for Mrs. Forbush.... A number of Women here. Mrs. Hephzibath Maynard and her son’s wife, Mrs. How, Mr. David Maynard’s wife and his Brother Ebenezer’s, Captain Forbush’s and Mr. Richard Barns’s. My son Ebenezer went out for most of them. At night I resign my Dear Spouse to the infinite Compassions, all sufficiency and sovereign pleasure of God and under God to the good Women that are with her, waiting Humbly the Event.”3

Mary Louise Fowler wrote to her pregnant sister Nettie in 186, when Nettie was in Europe with her husband: “I think of you in anticipation of your coming trial. I know you will have all that can be procured under the circumstances, but it would relieve me of great anxiety if you were in our best bed-room where I could nurse you as only a mother or a sister can.”4 The ethic of a proper childbirth was, for the overwhelming majority of women in the United States, rich or poor, and over a long period of time, a home birth attended by caring, concerned women relatives and friends. One mid-nineteenth-century woman put it this way: “A woman that was expecting had to take good care that she had plenty fixed to eat for her neighbors when they got there. There was no telling how long they was in for. There wasn’t no paying these friends so you had to treat them good.”5

To this women’s world husbands, brothers, or fathers could gain only temporary entrance. In one instance, a new father was invited in to see his wife and new daughter, but then, “Mrs. Warren, who was absolute in this season of female despotism, interposed, and the happy father was compelled, with reluctant steps, to quit the spot.”6

The women’s world around the home birthing bed that is revealed in letters and diaries represents the existence of a specific female group identity among women. Women could write and speak to each other about intimate details of confinement-related care; they could confide their innermost thoughts about their coming motherhood. While nineteenth-century conventions did not permit discourse about such private matters in public, among themselves, in private, women could and did speak more freely. In their private writings and around the confinement bed, women identified with each other’s concerns, shared their wisdom, and united, as women, in the knowledge that they were not alone in their problems. The roles women played for one another were not just psychological support but also involved very specific duties to aid labor and delivery along, such as applying olive oil and perineal massage.7 In the words of one observer, women could be counted on to “know what to do without telling.”8 Another wrote, “Only a woman can know what a woman has suffered or is suffering.”9

Physician-Attended Home Childbirth

Despite the very female nature of the childbirth experience, women in eighteenth-century American cities who could afford medical aid began inviting male physicians to attend them during labor and delivery. They did so because they thought doctors could improve on their chances of survival and comfort. They had no intention at that time to give over decision-making authority to the doctors. They wanted medical help and sought it in very specific ways. For a long time historians assumed that, when male doctors began attending normal births, women’s birthing networks disappeared.10 But more recent research has shown that women continued to help each other and to control childbirth events until birth moved to the hospital.11

The “medicalization” of childbirth did not occur in the eighteenth century, when physicians first attended obstetrical cases; nor did it develop in the nineteenth century as physicians became established figures in the home birthing rooms of most middle- and upper-class American women. Childbirth was not medicalized, in the sense that we use the term today to mean under physician control, until birth moved to the hospital.

In the home-birth period, physicians entered women’s world around the birthing bed, and they learned how to act within a domain that was not their own. Some doctors learned it better than others as they tried to create a place for themselves in women’s domestic world. One physician realized that “obstetrical practice is an intimate intrusion into family affairs.”12 Some doctors fit right in. “Dr. Marsh stalked into the room,” wrote one birthing woman, “like an easy old friend. In a few minutes he was playing with Louisa [a child] and talking to me about the new baby. ... He did what was expected of him, ate a bite of breakfast with Kate [her friend in attendance], then made himself so much at home, he put us all at ease. He took Louisa on his lap, and soon had her speaking pieces and singing.”13 Dr. Daniel Cameron, who practiced medicine in Wisconsin in the 1850s, told of one of his obstetric calls: “Wednesday, a week ago, was called on to confine Mrs. Conklin.... Sat up all night and talked scandal with some Cornish women in attendance.”14 Successful physicians were those who learned to relax and interact with the birthing woman’s female attendants.

In the eighteenth century, physicians used opium and bleeding to help ease labor’s discomforts, and by the end of that century they applied forceps to help along a protracted labor. In the mid-nineteenth century they added anesthetics, primarily ether and chloroform, for effective pain relief. The possibility of a difficult delivery, which women fearfully anticipated, and the knowledge that physicians’ remedies could provide relief and successful outcomes encouraged women to seek out practitioners whose obstetric armamentarium included drugs and instruments.15

Throughout the nineteenth century, the decision of whether to employ a physician remained where it had been traditionally, with birthing women and their female relatives and friends. Often the women consulted with their husbands, who paid the bill. The birthing woman, her midwife, and her assistants might have decided to call a doctor after labor had begun, and they then gave or withheld permission for each procedure suggested. Home birthing rooms usually contained the traditional female attendants right alongside the newer medical attendant, and these people all discussed and decided what procedures might be employed during the labor and delivery, the doctor adding his voice to the others. William Potts Dewees, for example, wanted in one case to take blood from a laboring woman: “I represented to the friends of the patient, the danger of her case.... They agreed to the trial.”16 Although male physicians had broken the gender barrier and birth was no longer exclusively a women’s event, women, by making their own choices about attendants and procedures, continued to hold the power to shape events in the birthing room.

As new obstetrical techniques became available—especially forceps and anesthesia—they worked to the advantage of physicians, who held a monopoly over their use.17 Centuries of female traditions and the domestic environment in which those traditions operated, however, continued to work to the advantage of women. Both women and physicians had an expertise about childbirth, physicians’ based on textbooks and theory and women’s based on experience. Some physicians welcomed the knowledge of the birthing woman and her attendants. Chicago physician Morris Fishbein admitted that when he was a medical student in the second decade of the twentieth century, he “received better instruction” from a poor Irish woman whose eighth birth he attended than he ever had in any classroom. “She was thoroughly familiar with every step of the process.”18 Others found well-informed women intimidating. One physician recalled, “A young doctor, fresh from medical college, can pass many embarrassing moments in the presence of the neighborhood midwife.”19

As advisers in women’s homes, physicians had to learn that while their words could be added to the other voices in the room, their views might or might not predominate. Sometimes considerable tension resulted from differences of opinion. An Oklahoma physician explained to his fellow doctors, for example, that he would never try to shave a patient’s pubic hair (a procedure associated with the understanding of germ transmission at the end of the nineteenth century) even though he thought it would help prevent infection. “In about three seconds after the doctor has made the first rake with his safety [razor], he will find himself on his back out in the yard with the imprint of a woman’s bare foot emblazoned on his manly chest, the window sash around his neck and a revolving vision of all the stars in the fermament [sic] presented to him. Tell him not to try to shave ’em.”20 Similarly, Dr. J. H. Guinn of Arkansas City, Kansas, wrote of the impossibility of achieving sterile conditions in urban or rural homes “in which there are five or six neighbor women, and, perhaps, the mother of the patient—all mothers of large families of children.” The doctor could not, he thought, under such observation, “strip his patient and go at her with soap and scrub-brush, lather and razor.”21 Another practitioner put it bluntly: a doctor, he wrote, “has his living to make and cannot be too insistent with his patient over whom, usually, he has no control.”22 Doctors could offer advice, but they did not have the freedom of action in women’s homes that they later achieved in hospitals.

The pressures some physicians felt in home birthing rooms did not abate as long as birth remained a home event. Dr. Samuel X. Radbill, who delivered babies in Philadelphia in the 1930s before limiting his practice to pediatrics, remembered the discomfort of working under the close observation of parturients’ female friends and relatives. In one delivery he attended, the birthing woman’s mother, who, after two days of labor, was extremely anxious for her daughter’s welfare, “came rushing in in a rage, brandishing the [kitchen] knife and yelling, ‘Doctor, if my daughter dies, I kill you!’” Radbill reported with great relief that shortly after that “the baby was safely delivered and everybody was as delirious with joy as they had been frantic with terror before.”23

nder such conditions physicians had to keep a cool head and a steady hand. Radbill was relieved when a nearby hospital opened a maternity ward, where he could deliver his patients outside their homes and away from the pressures of the woman’s family. From such examples, it is clear that physicians did not have the kind of control they came to want in obstetric cases until birth moved to the hospital. Home birth was medicalized only as much as women wanted it to be.

Birth Moves to the Hospital

In the twentieth century, birthing women and the growing number of physicians who specialized in obstetrics increasingly found fault with these home-based childbirth practices. Application of the new knowledge about bacteriology and germ transmission made home deliveries, even under the best of conditions, difficult to manage. Bacteriology was only one of five forces that pushed both birthing women and their physicians to try to modernize birth by moving it to the hospital.

The first factor propelling birth into the hospital was a continuation of fears about the dangers of childbirth; in the words of nineteenth-century women, it was the “shadow of maternity,” a burden women carried through their reproductive years. The burden grew from high fertility rates and the ever present possibility of death or debility that concerned women as soon as they found themselves pregnant.24 Women worried throughout their nine months of pregnancy that they would not survive the ordeal or that they would be maimed in the process. Clara Lenroot confided in her diary when she found herself pregnant in 1891, “It occurs to me that possibly I may not live.... I wonder if I should die, and leave a little daughter behind me, they would name her Clara. I should like to have them.” Three days later she again worried, “If I shouldn’t live I wonder what they will do with the baby! I should want Mamma and Bertha [sister] to have the bringing up of it, but I should want Irvine [husband] to see it every day and love it so much, and I should want it taught to love him better than anyone else in the world.”25 Lillie M. Jackson recalled her 1905 confinement: “While carrying my baby, I was so miserable.... I went down to death’s door to bring my son into the world, and I’ve never forgotten.”26

The shadow of maternity, which repeatedly darkened women’s lives, moved women to seek to improve and make safer their maternity experiences. It led women to seek medical expertise in their confinements and helped them to appreciate, especially after germ theory was understood, the promise of the new medicine. They anticipated ...

Table of contents

- Table of Contents

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- PREFACE

- Introduction

- 1* - ALONE AMONG STRANGERS

- 2 * - KEEPING VIGIL

- 3 * - THE BEST BACKRUBBER

- 4 * - HE WANTS TO KNOW

- 5 * - PEACEFUL AND CONFIDENT

- 6 * - SIDE BY SIDE

- 7 * - WE DID IT

- EPILOGUE

- A NOTE ON SOURCES

- NOTES

- Acknowledgements