eBook - ePub

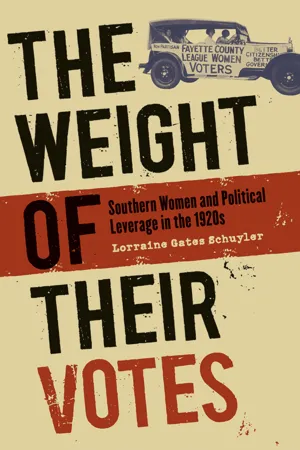

The Weight of Their Votes

Southern Women and Political Leverage in the 1920s

- 352 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

After the ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment in 1920, hundreds of thousands of southern women went to the polls for the first time. In The Weight of Their Votes Lorraine Gates Schuyler examines the consequences this had in states across the South. She shows that from polling places to the halls of state legislatures, women altered the political landscape in ways both symbolic and substantive. Schuyler challenges popular scholarly opinion that women failed to wield their ballots effectively in the 1920s, arguing instead that in state and local politics, women made the most of their votes.

Schuyler explores get-out-the-vote campaigns staged by black and white women in the region and the response of white politicians to the sudden expansion of the electorate. Despite the cultural expectations of southern womanhood and the obstacles of poll taxes, literacy tests, and other suffrage restrictions, southern women took advantage of their voting power, Schuyler shows. Black women mobilized to challenge disfranchisement and seize their right to vote. White women lobbied state legislators for policy changes and threatened their representatives with political defeat if they failed to heed women’s policy demands. Thus, even as southern Democrats remained in power, the social welfare policies and public spending priorities of southern states changed in the 1920s as a consequence of woman suffrage.

Schuyler explores get-out-the-vote campaigns staged by black and white women in the region and the response of white politicians to the sudden expansion of the electorate. Despite the cultural expectations of southern womanhood and the obstacles of poll taxes, literacy tests, and other suffrage restrictions, southern women took advantage of their voting power, Schuyler shows. Black women mobilized to challenge disfranchisement and seize their right to vote. White women lobbied state legislators for policy changes and threatened their representatives with political defeat if they failed to heed women’s policy demands. Thus, even as southern Democrats remained in power, the social welfare policies and public spending priorities of southern states changed in the 1920s as a consequence of woman suffrage.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Weight of Their Votes by Lorraine Gates Schuyler in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & North American History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter One

Now You Smell Perfume

The Social Drama of Politics in the 1920s

WHAT WILL YOU BE? A Man or a Jelly Bean?”1 This is the question that antisuffragists posed to southern men on the eve of ratification. For years, and at an even more fevered pitch in the last months before the Nineteenth Amendment was ratified, antisuffragists made apocalyptic predictions of the doomsday that would arrive in the South if women received the vote. According to these “antis” the entire southern social order would collapse in the wake of woman suffrage, as it threatened to bring “Negro Domination” and the ruin of the white southern family. While the antis’ most dramatic claims failed to materialize, the sudden influx of women into public politics transformed the social drama of politics and challenged the supremacy of white males in ways that many antisuffragists had predicted with dread.2 As white and black women embraced their new status as voters, the Nineteenth Amendment blurred the lines of gender and race that were so central to the order of the Jim Crow South.

IN THE YEARS immediately preceding the ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment, white southern men sat atop a political system exclusively within their control. The threats from Populists, Republicans, African Americans, and even poor whites had been answered with poll taxes, understanding clauses, literacy tests, violence, and other legal and extralegal means of disfranchising disruptive voters. Voter participation rates in the South were appallingly low, even by low national standards, and on election days politically active southern white men gathered at the polls to share in the male political rituals of smoking, spitting, brawling, coarse joke-telling, drinking (despite laws to the contrary), and, not least, casting ballots, which symbolized their superiority to white women and children, all African Americans, and even other white men who lacked the means or education to share in southern political life.

Determined to protect this status quo, southern antisuffragists, both male and female, used theological, “scientific,” and sociological arguments to condemn women’s demands for the ballot.3 Ministers, leading male politicians, and female antisuffragists used biblical injunctions to remind southerners of the divine inspiration for woman’s separate sphere. Moreover, they argued, women were mentally and physically unfit for the strenuousness of politics and public life. But more often, antis based their attacks on the threat that woman suffrage posed to the southern social order. Woman suffrage, they argued, would foster unhealthy competition between men and women, “discourage marriage,” and “lessen women’s attractive qualities of modesty, dependence, and delicacy.”4 While antisuffragist men were often content to let the women antis take center stage in public debates over the issue, thereby furthering their contention that southern ladies did not really want the ballot, antisuffragist broadsides reveal surprisingly frank concerns about the effects of woman suffrage on southern manhood.

One broadside put it simply, “Block woman suffrage, that wrecker of the home.”5 Another pamphlet warned that “more voting women than voting men will place the Government under petticoat rule.”6 It was a cartoon published in Nashville, however, that really got to the heart of the matter. Titled “America When Femininized [sic],” it pictured a rooster left to care for a nest full of eggs as the hen departed the barn wearing a “Votes for Women” banner. This scene was supplemented by text that cautioned “Woman suffrage denatures both men and women; it masculinizes women and feminizes men.” The broadside warned that the effects of woman suffrage, this “social revolution . . . will be to make ‘sissies’ of American men—a process already well under way.”7 Another notice printed in Montgomery, Alabama, highlighted the same themes when it asked: “Shall America Collapse from Effeminacy? . . . The American man is losing hold. He is swiftly but surely surrendering to the domination of woman.”8

As these broadsides suggest, white southern men had a lot to be anxious about in 1920. In addition to the threat of woman suffrage, recurrent agricultural crises, labor unrest, a rising tide of African American activism, the Great Migration, and social changes symbolized by flappers and an increasingly independent youth culture all combined to make white southern men feel very uneasy as they entered the postwar decade.9 Historian Nancy MacLean has demonstrated that many white southerners believed that the hierarchical relations of power that provided the foundation for southern society were in danger of collapse, and hundreds of thousands turned to the Second Ku Klux Klan as a way to restore order.10 Nevertheless, many historians looking back on the 1920s have contended that antisuffragists’ claims were mere “political hyperbole.”11 To many white men who watched southern women go to the polls for the first time in 1920, however, the dire predictions of antisuffragists must have seemed eerily prescient.

Antisuffrage broadside (courtesy Tennessee State Library and Archives)

Antisuffrage broadside (courtesy Bennehan Cameron Papers, Southern Historical Collection, Wilson Library, the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill)

DESPITE DETERMINED opposition from the region’s leading men, women in nearly every southern state cast their first ballots in November 1920.12 In August 1920, Tennessee’s legislature provided a narrow margin in support of ratification, becoming the essential thirty-sixth state to ratify the Nineteenth Amendment and joining Arkansas, Kentucky, and Texas as the only southern states to vote in support of the federal amendment. By contrast, many other southern states not only refused to ratify the amendment but passed rejection proclamations. Alabama, Georgia, South Carolina, and Virginia sent such resolutions to Washington, announcing to the nation their antipathy for woman suffrage. Even after the Nineteenth Amendment was added to the Constitution, Mississippi and Georgia refused to make the necessary changes in their registration laws to permit women to vote in the 1920 presidential election. Indeed, as one historian has noted, “the all-male electorate of Mississippi rejected woman suffrage in a referendum the same day that women in most of the country voted for the first time.”13 Up until the last moment, it seemed, southern white men fought to maintain the political sphere as their own domain.

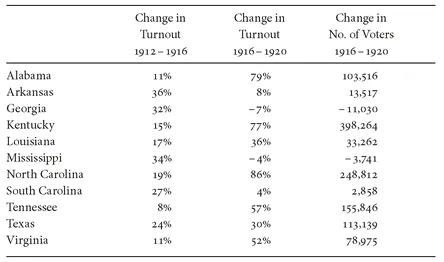

Once that moment had passed, the presence of women voting, politicking, and lobbying in spaces formerly reserved for men marked a profound change on the southern political landscape. The appearance of women, both white and black, made the polls look different on election day and signaled that formal politics would no longer be the exclusive privilege of white men. As the Richmond Times Dispatch editorialized in 1923, “Somehow we couldn’t visualize members of the fair sex in Virginia taking part in ‘unfair’ politics. The whole thing was incongruous.”14 Figure 1 and table 1, showing the increase in the popular vote in the first presidential election in which women voted, provide visual evidence of how widespread the disruption was for white men who had gone to such lengths to retain control of southern politics.15

In Alabama, 79 percent more voters, more than 100,000 additional people, cast their ballots for president in 1920 than had done so in 1916. In North Carolina, nearly a quarter million additional voters crowded the polls on election day in 1920, an increase of 86 percent. In Louisiana, more than 47,000 women registered to vote in the 1920 presidential election.16 Region-wide, the increase in voting was 56 percent in the states in which women were permitted to vote. The addition of more than one million new voters to the southern polls in November 1920 was not due exclusively to the entrance of women into the system, but in the absence of new women voters, Georgia and Mississippi suffered declines in the popular vote cast for president that year of 7 and 4 percent, respectively. While we cannot know precisely how many southern women voted in 1920, the presence of women at the polls was widespread and numerically strong enough to make southern white men take note.17

Newspapers across the South took great notice of the first ballots cast by members of the “fair sex.” On election day 1920, Virginia women went to the polls by the tens of thousands, and the state’s largest newspaper noted that women “were early at the polls and stayed late” providing instructions to first-time voters and working diligently to get out the vote.18 On the day after the election, the editor of the Richmond Times Dispatch hailed the political involvement of the state’s women: “Because of the lack of a strong minority party, Virginia campaigns have become rather cut and dried, but this year the women have given the color and zest needed for a complete revivification.” 19 A South Carolina newspaper headline declared, “Women at Booths Attract Attention,” and articles in newspapers throughout the South described the spectacle of women voters at the polls and provided local tallies of their participation in the day’s election.20

Figure 1. Change in Voter Turnout after Suffrage, 1920 Presidential Election

Table 1. Trends in Voter Turnout before and after Suffrage, 1912 - 1920

Source: The data utilized to create this table and table 2 were made available through the online database U.S. Historical Election Returns from the University of Virginia Geospatial and Statistical Data Center, ‹ http://fisher.lib.virginia.udu/collections/stats/elections/us.elections ›.

Once the Nineteenth Amendment was ratified, politically active white women worked to make the polling places their own, and they transformed the polls into respectable spaces. In its election assessment, the Charlotte Observer lamented that in elections past, “there were plenty of idle moments in which to pass joke and quip; the air was usually foul with tobacco smoke and the floor spattered with juice and littered with paper, and sometimes the men would become unduly argumentative and a fight or two would enliven the proceedings.” But with the arrival of women at the polls, the men “found no time to indulge in the amenities that characterized the elections of former days; instead of it being a day of fun and leisure for them, it was a day of diligent application to work.”21 When the women of Tennessee went to the polls for the first time, the Chattanooga News noted that “there was certainly a contrast in the election scenes today and in the city election four years ago.” In deference to the women voters, “loud talking and the threats of betting are absent,” and “everything was orderly as a Sunday school assemblage.” 22 The election in Newberry, South Carolina, was described as “a very quiet and ladylike” one, a characterization antisuffragists might have predicted with fear.23

On the morning after the election, one South Carolina newspaper declared, the “Sun Still Shines Though Women Vote.” Many men, however, might have disagreed with the reporter’s assessment that “nothing untoward happened,” as men in the courthouse “took off their hats, failed to chew the usual amount of tobacco, and stood aside for the ladies, while waiting their turns at the ballot box.”24 In yet another southern polling place, the policeman assigned to the precinct facilitated the balloting by holding women’s babies as they cast their ballots.25 Women in Aiken, South Carolina, were credited with casting their ballots “with all sang-froid of old timers,” but it was clear from newspaper accounts that times had changed: “Husbands and wives went to the polls together; mothers and daughters drove up and alighted from their automobiles; young matrons left their babies in go-carts and carriages on the pavement or led their little tots along with them.”26 All of these changes that women voters wrought at the polls prompted one Georgia observer to comment, “If I hadn’t known it was election day I would have thought the men and women were gathering for an afternoon reception or community sing.”27

Throughout the decade, women voters worked to “clean up” politics in general and polling places in particular.28 In Fulton County, Georgia, white women voters protested various “indignities” and “inconveniences” they suffered as they exercised the franchise. While highlighting a particularly “disgraceful episode” involving “two drunks” and “a gambling matter,” which had obstructed voters’ access at the Peachtree and Sixth Street precinct, these women went on to chastise public officials for forcing voters to “stumble over perfume and candy counters” in local retail establishments that served as polling places on election day.29 Although these women sincerely believed that such inconveniences interfered with the “dignity” of voting, many of Fulton County’s white men must ha...

Table of contents

- Table of Contents

- Table of Figures

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- Chapter One - Now You Smell Perfume

- Chapter Two - More People to Vote

- Chapter Three - Making Their Bow to the Ladies

- Chapter Four - Not Bound to Any Party

- Chapter Five - The Best Weapon for Reform

- Chapter Six - No Longer Treated Lightly

- Chapter Seven - To Hold the Lady Votes

- Conclusion

- Appendix

- Notes

- Bibliography