eBook - ePub

The Best of Southern Food

Selected Essays from Southern Cultures, 2008-2014

- 176 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Best of Southern Food

Selected Essays from Southern Cultures, 2008-2014

About this book

Nourishment, nostalgia, Native ingredients and global influences. Southern Cultures’s debut “best of” collection gets straight to the heart of the matter: food.

For those of us who've debated mayonnaise brand, hushpuppy condiment, or barbecue style—including, in some quarters, whether the latter is a noun or a verb (bless your heart)—we present here a collection equal to our passions.

Culled from our best food writing, 2008–2014, this special volume serves up tomatoes, turtles, molasses, Mother Corn and the Dixie Pig, bourbon, gravy, cakes, jams, jellies, pickles, and chocolate pie. Dig in! And stay tuned for more “best of” collections to come.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Best of Southern Food by Harry L. Watson, Marcie Cohen Ferris, Harry L. Watson,Marcie Cohen Ferris in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & North American History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

“The Deepest Reality of Life”

Southern Sociology, the WPA, and Food in the New South

“Thus, the way of the South, as the way of culture, has also been the way of history and the way of America.”—Howard W. Odum1

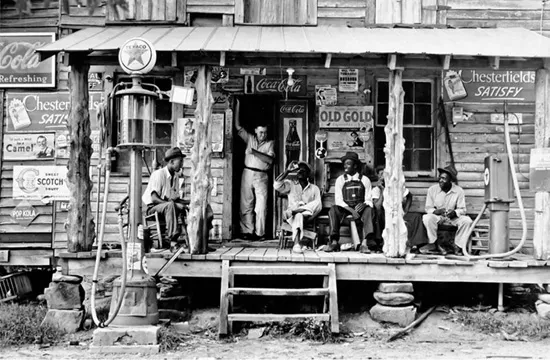

Roy Stryker oversaw the Farm Security Administration photo-documentary project in Washington, D.C., in 1939, and when serendipity brought Dorothea Lange to D.C. for a couple of weeks, he was eager to convince her to work with sociologists Margaret Jarman Hagood and Harriet Herring in North Carolina. Within the month, Lange was on a train bound for North Carolina. Gordonton, 1939, photographed by Dorothea Lange, courtesy of the Collections of the Library of Congress.

A vast network of reform spread across the South in the first decades of the twentieth century as an army of progressive southerners, white and black, struggled to bring social justice, public health programs, improved diet, Prohibition, scientific agriculture, and education to the South. Private and public battles were waged between the “southern way of life” and a vision of a more ordered, cohesive, and humanitarian South. New domestic science departments, agriculture experiment stations, home and farm extension programs, industrial colleges, settlement schools, and university departments symbolized a cautiously changing South, but one still struggling under the chokehold that race and class had on the region. High rates of tenancy and sharecropping, unhealthy work environments in textile mills, and relentless poverty made the South a virtual laboratory to examine illiteracy, public health issues, and substandard living conditions in rural America. Food provides a window on to this transitional time as southerners struggled to embrace modernity. The following essay explores one “moment” in this historical sweep: the 1920s to 1940s New South era of social science research and New Deal programs that identified “southern diet” and “southern cookery”—two distinctly different views of the region’s food—as both the South’s greatest problem and most beloved treasure.2

SOUTHERN SOCIOLOGISTS AND THE “GEOGRAPHY OF NUTRITION”

In late February 1920, Columbia-trained sociologist Howard Odum, a native of Georgia, arrived at the University of North Carolina, where he founded the university’s and the South’s first Department of Sociology and School of Public Welfare. As North Carolina’s extension service and home demonstration agents traveled county to county to preach the gospel of vegetable gardens and diversified, small-scale agriculture in the 1920s and ’30s, Odum and his colleagues introduced the discipline of “regional sociology,” which brought the tools of social science to address contemporary problems. He joined documentarians, government officials, public health physicians, revenuers, reformers, scholars, and statisticians, who turned their attention to the Depression-era South and responded to President Franklin Roosevelt’s infamous designation of the region as the “Nation’s No. 1 economic problem.”3

Odum’s new Institute for Research in Social Science (IRSS), founded in 1924, assembled a diverse group of scholars, including UNC-trained sociologists Rupert Vance and Arthur Raper, and Guy B. Johnson, who studied black folk culture in the South. In his massive ethnography of the South, Southern Regions of the United States (1936), Odum identified diet and folkways as important aspects of regional culture. He described “two contrasting pictures” of the culinary South, a world of plenty and a world of deprivation: “One portrays the excellence of southern cooking with its contributions to the art of living; the other the subsistence diet of the masses of marginal folk, commonly ascribed as a major factor in deficiencies of vitality and health.” Odum connected the substandard diet of the “masses” to the South’s problems in health, politics, race relations, and leadership and argued that knowledge of regional folk culture was essential to charting a progressive future for the South. These issues, and more, were at the center of Odum’s commitment to regional planning, and his dream to end the South’s insularity and successfully integrate the region into the nation.4

In the late 1930s, Stryker sought less depressing photographs focused solely on poor, struggling Americans. Stryker wrote photographer Jack Delano in 1940, urging him to “Emphasize the idea of abundance—the ‘horn of plenty’ and pour maple syrup over it. I know your damned photographer’s soul writhes, but to hell with it. Do you think I give a damn about a photographer’s soul with Hitler at our doorstep?” Stove left behind by migrants, Belcross, North Carolina, 1940, photographed by Jack Delano, courtesy of the Collections of the Library of Congress.

Two divergent schools of regionalist thought emerged in southern universities at this time: a regionalism based in research, analysis, and planning, promoted by Howard Odum and Rupert Vance at Chapel Hill, and the pastoral vision of a southern utopia in harmony with nature and “rural virtues” touted by the Agrarians, a group of twelve scholars at Vanderbilt University. The Agrarian manifesto, I’ll Take My Stand (1930), made a case for preserving southern agricultural heritage and rural values by shielding the region from the invasive forces of industrialization and technology couched in the “positivism” of New South boosters.5

Sentimental depictions of the home-raised food of hardworking white farmers in the early South—and the moral value of their labor—were key to the Agrarian narrative. Consider Andrew Nelson Lytle’s commentary on the groaning dining table of a Tennessee “countryman” before industrialization: “His table, if the seasons allow, is always bountiful. The abundance of nature, its heaping dishes, its bulging-breasted fowls, deep-yellow butter and creamy milk, fat beans and juicy corn, and its potatoes flavored like pecans, fill his dining-room with the satisfaction of well-being, because he has not yet come to look upon his produce at so many cents a pound, or his corn at so much a dozen … Each dish has particular meaning to the consumer, for everybody has had something to do with the long and intricate procession from the ground to the table.” The ideal world that Lytle depicts is distinctly white, devoid of any hint of the institution of slavery. The black cook who would have prepared the meal, alongside the white farm wife and her daughters, is invisible in Lytle’s southern Camelot. Lytle and the Agrarians ignored the enormous changes in southern agriculture in the 1930s, which made self-sufficiency—the ability of a farmer to provide food for his family from a garden and livestock—impossible for white and black tenant farmers bound by crop liens and the volatile cotton and tobacco markets.6

Chapel Hill sociologist Rupert Vance understood the economic and social challenges of the small family farmer and sharecropper in the New South. As a child in rural Arkansas, he had contracted polio and lost the use of his legs. Vance later witnessed his own father lose his cotton farm to bankruptcy. In 1929, Vance drew upon his recently completed dissertation, “Human Factors in Cotton Culture,” which later became a classic in southern sociology. He pointed to the working conditions of what he labeled the “cotton culture complex,” the destructive system of plantation agriculture that effectively exhausted both the soil and generations of southern laborers and small farmers, and observed that “Among the most obvious of the material culture traits associated with cotton are the food habits of its growers.” Vance described the inadequate diet of the white and black working poor, a familiar food pattern in all regions in the South that were strapped by poverty in the first decades of the twentieth century. “The Negro cropper, the white tenant, and the small cotton farmer live upon a basic diet of salt fat pork, corn bread, and molasses,” wrote Vance. “This forms the ‘three M diet,’ meat, meal, and molasses … when cotton farmers purchase food, these are the articles of diet they purchase; first, because all three are cheap, and second, because food likes and dislikes come to be matters of habit imposed by culture.”7

Vance’s focus on the relationship between culture and regional diet was groundbreaking. “Somewhere on the outer edge of the uncharted field of human geography,” wrote Vance, “lies an undeveloped sector, the geography of nutrition.” Recognizing that the South had become a research site for public health physicians who investigated the “biology” of nutritional diseases such as pellagra and rickets, Vance saw similar possibilities for social scientists who studied “the human geography of diet” in the South. Despite its abundant plant and animal life, Vance noted the region’s “reputation for deficient diet.” His explanation for this conundrum reads like a contemporary definition of foodways: “When a people in the midst of a land capable of variety limit their diet to a few staples they are in the grip of tradition.” He turned to the cultural and folk history of the region to document the origins of food patterns in an agricultural system that left large numbers of southerners impoverished, hungry, and sick. “Behind the folk stands a tragic history,” wrote Vance. “What we need to know is that, in spite of its tragic history, the mold in which the South is to be fashioned is only now being laid.” Layering the region’s history with detailed survey information drawn from hundreds of home demonstration agents across the South, Rupert Vance underscored the impact of region, class, race, and education upon “the South’s Heritage of Food.”8

Just as Vance arrived at the University of North Carolina to join the Department of Sociology, William Terry “W. T.” Couch, a recent UNC history graduate, joined the staff of UNC Press, where he worked with director Louis Round Wilson. In 1932, Couch was appointed director of the Press after Wilson left for the University of Chicago. Under Couch’s leadership, the Press’s series on “social studies” flourished and included publications by Vance, Odum (who tirelessly fought for the emphasis on regional social science studies at the Press), and his own edited volume, Culture in the South (1935). This collection of essays examines southern social, economic, and political life and was Couch’s response to the work of the Agrarians. Couch hoped to move beyond the debate between agrarianism and industrialization by presenting a progressive vision for the South based on research, scholarship, and reform. He developed this vision, and an equally powerful commitment to empower all southerners through their own stories, when he was appointed regional director of the southeast division of the Federal Writers’ Program in 1938.9

Many of the contributors to Couch’s Culture in the South included ethnographic descriptions of the diet and food habits of southerners in their work. In his own essay, “The Negro in the South,” Couch mixed economic and social analysis, folk culture, and stereotypical depictions of working-class African Americans. “Jim”—an imaginary sharecropper created by Couch to represent poor black sharecroppers—“doesn’t own a cow; for many years he has had no garden and the family has lived on fat back, corn pone, molasses, and ‘thickenin’ gravy.” In her essay on “The Industrial Worker,” Harriet Herring, a University of North Carolina sociologist and labor activist who specialized in the textile industry, described the idyllic vision of the improved diet of a Progressive-era white mill operative in the South: “The store that supplied him with food was able, because of increasing rapidity of distribution of such products, to tempt him continually with fruits and vegetables, while the community nurse and school teacher were all busy educating him to the need of this sort of food.”10

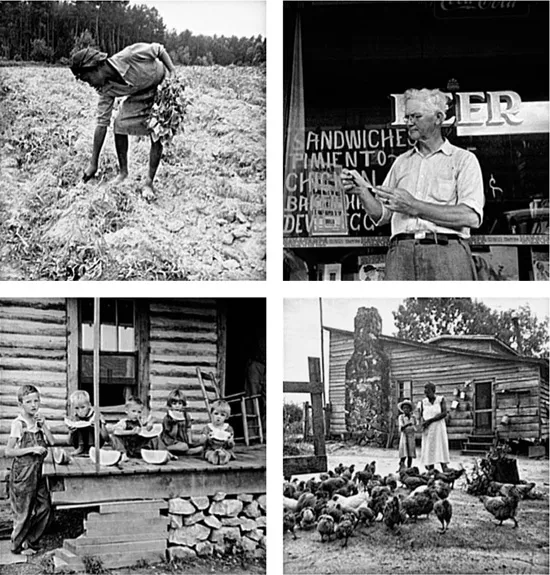

Dorothea Lange had an eye for photographing food—from field to table. In North Carolina in 1939, she photographed the daughter of sharecroppers as she planted sweet potatoes in Olive Hill (above, left); children of a millworker eating watermelon on the front porch of their rented log home near Roxboro (below, left); a handwritten menu in a store window in downtown Siler City, advertising pimiento cheese, chicken, baked ham, and deviled egg sandwiches (above, right); and a tenant woman feeding chickens on a rented farm in Granville (below, right). Courtesy of the Collections of the Library of Congress.

J. Wesley Hatcher, chair of the Department of Sociology at Berea College in the 1930s, wrote an essay on “Appalachian America” for Couch’s anthology. He described “three distinct classes” of Appalachian people and used food to illustrate their economic and social status. Hatcher’s racial stereotypes of mountain southerners identified education and...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Southern cultures

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Introduction

- Mother Corn and the Dixie Pig: Native Food in the Native South

- “A recourse that could be depended upon”: Picking Blackberries and Getting By after the Civil War

- “The Deepest Reality of Life”: Southern Sociology, the WPA, and Food in the New South

- Molasses-Colored Glasses: WPA and Sundry Sources on Molasses and Southern Foodways

- Canning Tomatoes, Growing “Better and More Perfect Women”: The Girls’ Tomato Club Movement

- “She Ought to Have Taken Those Cakes”: Southern Women and Rural Food Supplies

- Eat It to Save It: April McGreger in Conversation with Tradition

- An Eye for Mullet: Charles Farrell’s Photographs of the Brown’s Island Mullet Camp, 1938

- Theodore Peed’s Turtle Party

- Every Ounce a Man’s Whiskey?: Bourbon in the White Masculine South

- Mason–Dixon Lines: Chocolate Pie

- About the Contributors