eBook - ePub

For the Records: How African American Consumers and Music Retailers Created Commercial Public Space in the 1960s and 1970s South

An article from Southern Cultures 17:4, The Music Issue

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

For the Records: How African American Consumers and Music Retailers Created Commercial Public Space in the 1960s and 1970s South

An article from Southern Cultures 17:4, The Music Issue

About this book

“Record selling certainly had its glamorous moments; retailers could regale younger customers with stories of nightlife and even rubbing elbows with famous musicians and celebrities.”

African-American owned and operated record stores once provided vibrant venues for their communities, and close to 1000 of these shops operated in the South during their heyday.

This article appears in the 2011 Music issue of Southern Cultures.

Southern Cultures is published quarterly (spring, summer, fall, winter) by the University of North Carolina Press. The journal is sponsored by the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill’s Center for the Study of the American South.

African-American owned and operated record stores once provided vibrant venues for their communities, and close to 1000 of these shops operated in the South during their heyday.

This article appears in the 2011 Music issue of Southern Cultures.

Southern Cultures is published quarterly (spring, summer, fall, winter) by the University of North Carolina Press. The journal is sponsored by the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill’s Center for the Study of the American South.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

ESSAY

For the Records

How African American Consumers and Music Retailers Created Commercial Public Space in the 1960s and 1970s South

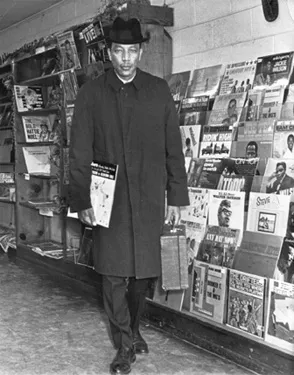

In the postwar United States, record stores like Curt’s (here) in Greensboro, North Carolina, were perhaps the place where consumers most commonly interacted with people who made their living from popular culture. Conservative estimates suggest that at least 400 to 500 black-owned record stores—and probably closer to one thousand—were in operation throughout the region during this period. Photograph courtesy of Curt Moore (here), owner of Curt’s.

Records is a market that can be used to brighten the future of lots of black people with jobs and higher prestige all over the country,” Jimmy Liggins announced in 1976 to the readers of the Carolina Times, Durham, North Carolina’s most prominent African American newspaper. Liggins, a minor rhythm and blues star of the 1950s, was publicizing his Duplex National Black Gold Record Pool, headquartered in Durham, which sought to “help and assist black people to own and sell the music and talent blacks produce.” With the aid of this “self helping program,” aspiring hit-makers could record and release music that Black Gold sold through mail order and at Liggins’s shop, Snoopy’s Records, in downtown Durham.1

Kenny Mann vividly recalls his frequent trips to Snoopy’s as a teenager in the late 1960s and early 1970s. Liggins “was like a god” to Mann and other young customers who patronized the store. “Everybody knew” Liggins and his two business partners, Henry Bates and Paul Truitt. “These guys, I was listening to them talk about bringing Tyrone Davis and Johnny Taylor and Al Green to town . . . It was fun to go [to their store] because it felt like the place to be; there were girls in there, and I was twelve, thirteen years old.” Not only that, but Mann “never felt the pressure to buy something” like he did in stores in his hometown of Chapel Hill, where white shopkeepers frequently followed young African American shoppers around their businesses, suspecting they might shoplift. “They had a double standard,” Mann remembers. Chapel Hill “really was set up as if they didn’t want to do business with us black people.” In sharp contrast, Liggins envisioned Snoopy’s as “our mall”— a “hang out” where black consumers could buy black music in a record store owned and operated by African Americans. Black-owned record stores like Snoopy’s represented a crucial nexus where African American enterprise, consumer culture, community, and of course, music all met. And by the early 1970s, Liggins was booking and promoting shows for Mann’s band, which eventually became Liquid Pleasure, the popular Chapel Hill-based funk and soul outfit still active today.

In the postwar United States, record stores were perhaps the place where consumers most commonly interacted with individuals who made their living from popular culture. Yet, while music writers and scholars have devoted much attention to black-oriented radio stations and record labels, we still know very little about the retail businesses from which African Americans purchased music, especially in the South. Conservative estimates would suggest that at least 400 to 500 black-owned record stores—and probably closer to one thousand—were in operation throughout the region during this period. An examination of the black-owned record stores in one southern state, North Carolina, not only reveals valuable insights about the southern marketplace for African American music, but also much about the broader role consumer culture played in southern black communities during these transitional decades. While desegregation measures were beginning to significantly alter the racial make-up of some areas of southern society, such as public schools, many African American record retailers and consumers hesitated to assimilate into white-dominated pop-music marketplaces. Black merchandisers envisioned the record trade as an arena in which African Americans could pursue a broader strategy of bolstering economic self-sufficiency and sustaining black public life. And by seeking out music from black-owned record stores, African American consumers partook in a vibrant form of commercial public life, a community-based consumer culture that welcomed shoppers regardless of their color, age, or financial means.2

AFRICAN AMERICAN ENTREPRENEURSHIP

African American entrepreneurship dates back centuries, but in the wake of the Civil Rights Movement, black communities in the South expressed renewed interest in harnessing business’ potential for self-empowerment. In response to business owners, politicians, and commentators who have oversold the economic benefits of African American-owned businesses, many scholars have produced strident critiques of the unfounded idealism of such boosterism. Scholars like historian Suzanne Smith argue that Motown Industries, Berry Gordy’s Detroit-based record label—which by the start of the 1970s was earning higher annual revenues than any other black-owned business in American history—neglected Detroit’s black residents and thus demonstrated “the myth of black capitalism,” echoing the famed African American sociologist E. Franklin Frazier’s skeptical assessment of black businesses. Yet, as another sociological study of black-owned businesses in the 1970s has demonstrated convincingly, “the black share of business firms in a city seems to have a substantial impact on the relative well-being of blacks in that city.” Indeed, in most municipalities with considerable concentrations of black-owned businesses, African Americans figured prominently in both local politics and in public-sector employment.3

Black business owners depended on the support and patronage of black consumers and almost always catered to the needs and desires of the surrounding African American community. Consequently, African American consumers could make suggestions about a black-owned store’s inventory, or express displeasure with its policies and practices, all without fear of retaliation or being...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- ESSAY For the Records: How African American Consumers and Music Retailers Created Commercial Public Space in the 1960s and 1970s South

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access For the Records: How African American Consumers and Music Retailers Created Commercial Public Space in the 1960s and 1970s South by Joshua Clark Davis in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & North American History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.