eBook - ePub

The Music Has Gone Out of the Movement

Civil Rights and the Johnson Administration, 1965-1968

- 384 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Music Has Gone Out of the Movement

Civil Rights and the Johnson Administration, 1965-1968

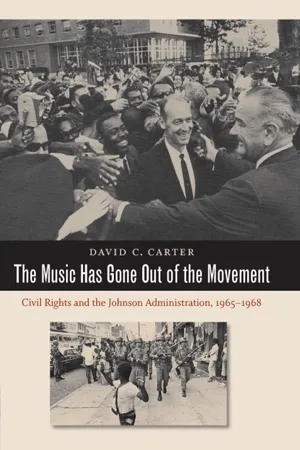

About this book

After the passage of sweeping civil rights and voting rights legislation in 1964 and 1965, the civil rights movement stood poised to build on considerable momentum. In a famous speech at Howard University in 1965, President Lyndon B. Johnson declared that victory in the next battle for civil rights would be measured in “equal results” rather than equal rights and opportunities. It seemed that for a brief moment the White House and champions of racial equality shared the same objectives and priorities. Finding common ground proved elusive, however, in a climate of growing social and political unrest marked by urban riots, the Vietnam War, and resurgent conservatism.

Examining grassroots movements and organizations and their complicated relationships with the federal government and state authorities between 1965 and 1968, David C. Carter takes readers through the inner workings of local civil rights coalitions as they tried to maintain strength within their organizations while facing both overt and subtle opposition from state and federal officials. He also highlights internal debates and divisions within the White House and the executive branch, demonstrating that the federal government’s relationship to the movement and its major goals was never as clear-cut as the president’s progressive rhetoric suggested.

Carter reveals the complex and often tense relationships between the Johnson administration and activist groups advocating further social change, and he extends the traditional timeline of the civil rights movement beyond the passage of the Voting Rights Act.

Examining grassroots movements and organizations and their complicated relationships with the federal government and state authorities between 1965 and 1968, David C. Carter takes readers through the inner workings of local civil rights coalitions as they tried to maintain strength within their organizations while facing both overt and subtle opposition from state and federal officials. He also highlights internal debates and divisions within the White House and the executive branch, demonstrating that the federal government’s relationship to the movement and its major goals was never as clear-cut as the president’s progressive rhetoric suggested.

Carter reveals the complex and often tense relationships between the Johnson administration and activist groups advocating further social change, and he extends the traditional timeline of the civil rights movement beyond the passage of the Voting Rights Act.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Music Has Gone Out of the Movement by David C. Carter in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & North American History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER ONE

Leapfrogging the Movement

The Howard University Speech and the Tragic Narrative

Seen from beyond the reach of earth’s atmosphere, Vietnam’s verdant sliver blurred into the South China Sea, the divided country’s “Demilitarized Zone” and borders with Laos and Cambodia as fluid from this perspective as they were to become to the thousands of men and women fighting and dying over them on the ground. In the gathering twilight, the faintly outlined island geographies of Cuba, Haiti, and the Dominican Republic hopscotched across the Caribbean. Los Angeles, Cleveland, Washington, and New York materialized as flecks of light, absorbing, enveloping, then reflecting into the now dark sky the faltering streetlights and glowing signs of Watts, Hough, Congress Heights, and Harlem. Unpaved rural roads of Louisiana and Mississippi did not register from above.

American astronauts James A. McDivitt and Edward H. White II commanded an unparalleled view through the small porthole of the Gemini 4 as they orbited the planet in the first days of June 1965, defying the logic of morning’s and evening’s sway. Newspapers around the world chronicled each moment in their four-day spaceflight. Americans reveled in Gemini’s successful sixty-two orbits of earth and argued passionately over whether to condemn or applaud White’s “insubordination” (so euphoric was the astronaut in the early moments of his tethered spacewalk—an American first—that he jovially refused Mission Control’s order to reenter the module, remaining outside for several minutes longer than was necessary to best a Soviet cosmonaut’s recent record).

The national exultation about the United States’ improving fortunes vis-à-vis the Soviets in the “space race” meant that two other news stories went largely unnoticed. On the eve of the Gemini 4 liftoff, Captain Edward J. Dwight Jr., one of a handful of black air force test pilots, leveled scathing criticisms against that branch of the military. When his confidential letter of complaint about discrimination brought no response from the military chain of command, Dwight elected to go public. In an interview in Ebony, he claimed to have endured systematic racial bias while serving as the first black in a training program for potential astronauts at Edwards Air Force Base in the Mojave Desert. One of Dwight’s commanding officers at Edwards allegedly asked the black pilot: “Who got you into this school? Was it the N.A.A.C.P., or are you some kind of Black Muslim out here to make trouble? . . . Why in hell would a colored guy want to go into space anyway? As far as I’m concerned, there’ll never be one to do it. And if it was left to me, you guys wouldn’t even get a chance to wear an Air Force uniform.” NASA officials later passed over Dwight when they selected pilots for additional astronaut training, and the air force reacted stonily to the accounts of Dwight’s mistreatment. Citing the military’s nondiscrimination policies, a spokesperson cryptically noted that Dwight had since “received another assignment.”1

On Wednesday, June 2, in a second story that received little scrutiny, three whites in a pickup truck cruising along a rural road a few miles outside of Bogalusa, Louisiana, had opened fire on two unsuspecting and newly appointed sheriff’s deputies. The fusillade struck Creed Rogers in the shoulder and O’Neal Moore in the head. Rogers survived, but Moore died where he fell. Both victims were African Americans.2

With Time and Newsweek cover stories and all the leading newspapers featuring every detail of the Gemini mission from liftoff to splashdown, the space race threatened to overshadow two major presidential addresses. June, the peak of commencement season, presented prime opportunities for presidential speeches geared to a national audience. And Lyndon Johnson, like the Gemini 4 astronauts, appeared to have his sights set on the larger world. Media-driven rumors about peace “feelers” to the Soviets and North Vietnamese circulated widely following his speech to Democratic Party loyalists in Chicago on June 3. Two days later, at Catholic University, the president called for greater dialogue with the Russian people. When he spoke of East and West joining to “walk together toward peace,” news commentators speculated that Johnson was also making an indirect overture for the North Vietnamese to come to the peace table.3

Five weeks earlier, the president had unilaterally deployed American Marines to the Dominican Republic, citing the need to protect American lives but equally concerned with foiling an allegedly communist-controlled countercoup against a ruling military junta. The simmering crisis in the Caribbean appeared to be stabilizing on terms favorable to White House interests in containing the Cuban “virus.”4

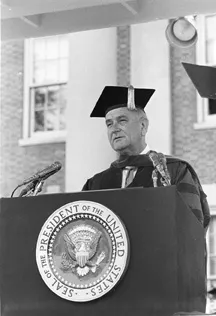

Friday, June 4, brought LBJ to Howard University, the flagship of the nation’s historically black colleges, for a midday commencement speech. Beset by foreign policy crises (the last civilian government in South Vietnam was unraveling and only a week away from a coup by its own military junta), he had refused to commit himself to the speech until twenty-four hours before graduation day. And he warned Howard president James Nabrit that any advance leak would likely lead to the cancellation of his speech.5

With the nation riveted by the reports of the Gemini craft as it revolved around the globe, Johnson began: “Our earth is the home of revolution. . . . Men charged with hope . . . reach for the newest of weapons to realize the oldest of dreams.” With no advance information about the content of the address, the opening must have sounded like yet another foreign policy statement to the nearly one thousand graduates and the many times larger number of predominantly African American well-wishers in the audience.6 But having linked the fortunes of American democracy with the process of revolutionary ferment abroad, he abruptly turned to the domestic front: “Nothing in any country touches us more profoundly, nothing is more freighted with meaning for our own destiny, than the revolution of the Negro American. . . . In far too many ways American Negroes have been another nation: deprived of freedom, crippled by hatred, the doors of opportunity closed to hope.”7

The president paid tribute to the catalytic effect of black-led civil rights protests: “The American Negro, acting with impressive restraint, has peacefully protested and marched . . . demanding a justice that has long been denied. The voice of the Negro was the call to action,” he conceded, but the federal courts and Congress deserved praise for having heeded this moral summons. On the drive over to the university, Johnson told his aides that “people need a hero, a strong leader who they can believe in.”8 Clearly he saw himself as that leader, but in his speech he was far more modest, briefly acknowledging his own involvement in securing civil rights legislation, first as Senate majority leader and then more notably as president.

Johnson applauded the impact of the newly enacted Civil Rights Act of 1964 and drew attention to the anticipated passage of the Voting Rights Act still pending before Congress. Those victories were essential, but, in the words of Winston Churchill, they were “not the end . . . not even the beginning of the end. But . . . perhaps, the end of the beginning.” “That beginning,” he intoned, “is freedom . . . the right to be treated in every part of our national life as a person equal in dignity and promise to all others.” He paused: “But freedom is not enough.” In the oft-quoted crux of the address, drafted by gifted speechwriter and Kennedy holdover Richard Goodwin, the president sought to illuminate shifting terrain in the ongoing struggle for black equality:

You do not wipe away the scars of centuries by saying: Now you are free to go where you want and do as you desire and choose the leaders you please. You do not take a person who, for years, has been hobbled by chains and liberate him, bring him to the starting line of a race, and then say you are free to compete with all the others, and still . . . believe that you have been completely fair. Thus it is not enough just to open the gates of opportunity. All our citizens must have the ability to walk through those gates. This is the next and the more profound stage of the battle for civil rights. We seek not just freedom but opportunity. We seek not just legal equity but human ability, not just equality as a right and a theory but equality as a fact and equality as a result.

The starting line metaphor was a powerful one. In private conversations with his aides, Johnson had often discussed the handicaps placed upon different participants in the race, comparing the challenge of aiding African Americans to “converting a crippled person into a four minute miler.”9 Allowing his audience little more than a breath to digest the crucial language about the inherent limitations in the concept of equal opportunity, he plunged ahead. He lauded the graduating seniors in his predominantly middle-class black audience, their achievements “witness to the indomitable determination of the Negro American to win his way in American life.” But the Howard students’ success was “only [part of] the story,” Johnson said. The speech proceeded quickly to a litany of grim statistics, a “seamless web” of adverse circumstances affecting the lives of “the great majority of Negro Americans—the poor, the unemployed, the uprooted and the dispossessed. . . . They still are another nation. . . . For them the walls are rising and the gulf is widening.”

In outlining the extent of black poverty, LBJ relied on—but never identified—an urgent report confidentially circulating in the upper echelons of the Department of Labor and in the White House itself. Authored by Assistant Secretary of Labor Daniel Patrick Moynihan, it was entitled “The Negro Family: A Case for National Action.”10 Despite gains in other areas of civil rights, patterns of residential segregation appeared to be deepening, particularly in the deteriorating urban centers where African Americans found themselves trapped by “inherited, gateless poverty.” Confined in the nation’s slums, Johnson declaimed, they made up a “city within a city.”

President Lyndon Johnson argues that “freedom is not enough” as he delivers the commencement address at Howard University on June 4, 1965. Courtesy of the LBJ Library.

The unseen hand of Moynihan again loomed large as the president spoke at length about the unique nature of black poverty. A long heritage of racial prejudice, stretching from the “ancient brutality” of bondage through the indignities of Jim Crow to the present ferment, differentiated African Americans’ experiences from those of other immigrant minorities. The speech, simplifying Moynihan’s complex arguments, undoubtedly glossed over the realities of long-standing prejudices and unique hardships faced by other immigrant groups whose efforts at assimilation and progress the president deemed “largely successful.” Johnson did, however, eloquently state the case that whites’ obsession with blackness represented a “feeling whose dark intensity is matched by no other prejudice in our society.” The psychic scars inflicted by white racism could be “overcome,” he asserted, subtly alluding to the refrain of the popular civil rights anthem, “but for many, the wounds are always open.”

“Much of the Negro community is buried under a blanket of history and circumstance,” Johnson explained, relating a metaphor that White House insiders remembered him using repeatedly that spring and summer to anyone who would listen.11 Given the Texan’s propensities for subjecting hapless bystanders to the now proverbial “Johnson treatment,” the blanket metaphor was guaranteed wide currency. “It was like you couldn’t pick up the blanket off a Negro at one corner, you had to pick it all up,” an aide reminisced. “It had to be housing and it had to be jobs and . . . everything you could think of.” The problems facing African Americans—and broadly implicating whites—were far too complicated. The president identified the “breakdown of the Negro family structure” as a crisis demanding immediate action. It was of paramount concern for those committed to economic justice to shore up the family, the “cornerstone of our society.” Without redress, it would be impossible “to cut completely the circle of despair and deprivation.”

These and other problems defied a “single, easy answer,” Johnson asserted, his tone reflecting what one reporter described as “a hint of bafflement and frustration” as he neared the end of his wide-ranging thirty-minute address. Full implementation and enforcement of existing and pending civil rights legislation would help, as would a broadening of the agenda to secure the Great Society. The battle to eradicate poverty, already declared by Johnson in 1964 as an “unconditional war,” would require further escalation. The president announced that he would convene a special White House conference in the fall of 1965 to attempt to come to grips with the full extent of the challenges facing African Americans in this “next and . . . more profound stage of the battle for civil rights” and to set an agenda for continued progress. The gathering would have as its theme “To Fulfill These Rights,” implicitly harking back to the landmark Truman era report entitled “To Secure These Rights” and its rhetorical antecedents in the Declaration of Independence. Having been interrupted a dozen times by applause—both the media and trusted aides familiar with the Texan’s prodigious ego kept meticulous count—Johnson briefly drew a burst of stifled laughter when in his evident excitement he elided his text and boasted that the proposed conference would be attended by “scholars, and experts, and outstanding Negro leaders of both races.”12

Johnson, at once deeply suspicious and desperately anxious to secure the approval of those with whom his predecessor, John Kennedy, had shared such an easy rapport, would of course enlist experts and scholars for this conference. Black and white “leaders” both in and out of government, from battle-hardened civil rights workers to lower-echelon bureaucrats, would also presumably have a crucial role to play. But the president concluded his address with an appeal

As the audience at Howard University listens, Johnson calls for a White House Conference with the theme “To Fulfill These Rights.” Courtesy of the LBJ Library.

to a much broader constituency when he called on all Americans to lead in “dissolv[ing] . . . the antique enmities of the heart which diminish the holder, divide the great democracy, and do wrong—great wrong—to the children of God.” The peroration hammered home a theme of “two nations” and the prejudice that kept them apart. The religious inflection, and the emphasis on redemptive possibilities, might have been that of Martin Luther King Jr.13

White House aide Richard Goodwin had grappled with the semantic shades of the concepts of freedom and equality in the Howard address’s introduction. The speech’s conclusion was a rhapsodic meditation on American justice, its stylistic lurch toward homiletics perhaps the excusable toll of the hours the time-pressed speechwriter had spent drafting and redrafting, his efforts unbroken by sleep. But then, in the final lines of text, came short, elegant phrases laden with meaning: “We have pursued [justice] faithfully to the edge of our imperfections. And we have failed to find it for the American Negro.” Taking a page from the Kennedy manual, Goodwin’s draft had Johnson close the Howard speech with one of the central metaphors of the New Testament. (The slain president had couched civil rights as a dilemma “as old as the Scriptures” on the night of Alabama governor George Wallace’s “stand in the schoolhouse door,” not coincidentally the night of Medgar Evers’s assassination in Jackson, Mississippi.)14 Drawing on the opening verses of the Gospel according to John, President Johnson called on both blacks and whites “to light a candle of understanding in the heart of all America. And, once lit, it will never again go out.”15

For LBJ to proclaim the need to expand the civil rights agenda to include basic economic rights seemed a logical outgrowth of the administration’s Great Society and antipoverty rhetoric. The Howard speech’s premise that “equal opportunity is essential, but not enough” reflected growing concerns within the civil rights communities and academia and in some elements of the federal government about the persistence of racial inequality and links between racism and poverty. Still, the president’s professed commitment to equality of “results,” expressed as clearly as it was, struck at least some in his immediate and wider national audience as a stunning deviation from a far more widely accepted definition of equality in terms of individual opportunity.16

A central question, then, is whether the Howard University speech represented a fundamental reconceptualization of civil rights within the Johnson White House from a narrow definition guaranteeing equality of opportunity to a broader vision promising equality of results. Or was the speech little more than a rhetorical watershed, an eloquently expressed vision of grander expectations designed to sway “hearts and minds” as much as swing votes for substantive departures in policy? How grounded in political reality was the oratorical flight taken by the president ...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- The Music Has Gone Out of the Movement

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Illustrations

- Preface

- CHAPTER ONE: Leapfrogging the Movement

- CHAPTER TWO: Romper Lobbies and Coloring Lessons

- CHAPTER THREE: The Cocktail Hour on the Negro Question

- CHAPTER FOUR: Bomb Throwers and Babes in the Woods

- CHAPTER FIVE: Mississippi Is Everywhere

- CHAPTER SIX: The Unwelcome Guest at the Feast

- CHAPTER SEVEN: Scouting the Star-Spangled Jungles

- CHAPTER EIGHT: Just File Them—or Get Rid of Them

- Epilogue

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Acknowledgments

- Index