eBook - ePub

Power to the Poor

Black-Brown Coalition and the Fight for Economic Justice, 1960-1974

- 376 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Power to the Poor

Black-Brown Coalition and the Fight for Economic Justice, 1960-1974

About this book

The Poor People’s Campaign of 1968 has long been overshadowed by the assassination of its architect, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., and the political turmoil of that year. In a major reinterpretation of civil rights and Chicano movement history, Gordon K. Mantler demonstrates how King’s unfinished crusade became the era’s most high-profile attempt at multiracial collaboration and sheds light on the interdependent relationship between racial identity and political coalition among African Americans and Mexican Americans. Mantler argues that while the fight against poverty held great potential for black-brown cooperation, such efforts also exposed the complex dynamics between the nation’s two largest minority groups.

Drawing on oral histories, archives, periodicals, and FBI surveillance files, Mantler paints a rich portrait of the campaign and the larger antipoverty work from which it emerged, including the labor activism of Cesar Chavez, opposition of Black and Chicano Power to state violence in Chicago and Denver, and advocacy for Mexican American land-grant rights in New Mexico. Ultimately, Mantler challenges readers to rethink the multiracial history of the long civil rights movement and the difficulty of sustaining political coalitions.

Drawing on oral histories, archives, periodicals, and FBI surveillance files, Mantler paints a rich portrait of the campaign and the larger antipoverty work from which it emerged, including the labor activism of Cesar Chavez, opposition of Black and Chicano Power to state violence in Chicago and Denver, and advocacy for Mexican American land-grant rights in New Mexico. Ultimately, Mantler challenges readers to rethink the multiracial history of the long civil rights movement and the difficulty of sustaining political coalitions.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Power to the Poor by Gordon K. Mantler in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Sozialwissenschaften & Nordamerikanische Geschichte. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

The “Rediscovery” of Poverty

“Poverty can now be abolished. How long shall we ignore this underdeveloped nation in our midst? How long shall we look the other way while our fellow human beings suffer? How long?”1 These words from The Other America, written by Michael Harrington in 1962, became one of the era’s most eloquent calls to action to address the plight of wrenching poverty amid plenty. An estimated fifty million souls, or roughly 27 percent of the population with an even higher percentage of children, lived in destitution compared to their fellow Americans, wrote Harrington. And unlike past eras, “the other America, the America of poverty, is hidden. . . . Its millions are socially invisible to the rest of us.”2

Harrington, a one-time member of the Catholic Worker movement in New York City before converting to socialism in the 1950s, became “the man who discovered poverty” in what is one of the most enduring creation myths in modern American history.3 A poignant piece of social criticism that became a bestseller and political and cultural touchstone, The Other America was read by some of the most powerful people in the nation, even President John F. Kennedy, the story goes. Believing that poverty indeed could be eliminated, federal officials and liberal economists then set forth with what would become the War on Poverty, conceived under Kennedy’s administration in 1963 and pursued, although never fully, by President Lyndon Johnson. While economists such as John Kenneth Galbraith had written about the deceptive and changing nature of the nation’s postwar economy, it was Harrington’s slim volume of less than two hundred pages that crystallized the thinking of the policy-making intelligentsia around poverty. It later would be called one of the “ten most important nonfiction books” in the twentieth century.4

Yet, as appealing as this narrative might be—especially to writers, scholars, and social critics—it distorts the context from which The Other America was born. “That book belonged to the movement,” wrote Harrington in his memoirs a decade later, “which contributed so much more to me than I to it.”5 Harrington did not go to the South in the early 1960s, but as his biographer states, “The movement . . . gave his politics a depth of human empathy and understanding lacking in the 1950s.”6 Those individuals so often linked to the War on Poverty’s origins, like Harrington, did not work in a vacuum, insulated from the growing crescendo of the era’s social justice movements, particularly the black and Mexican American freedom struggles and the early student movement. Rather, directly and indirectly, grass-roots activists influenced the ideas and timing of what would become the War on Poverty.

In fact, grass-roots activists of all races had been fighting their own war on poverty for a generation. They just did not call it that. Nor did they necessarily use the term “poverty.” They spoke instead of justice and freedom, which commingled issues from voting and equal access to public accommodations to jobs, welfare, and economic opportunity. As Ella Baker, long-term black activist and leading light of SNCC, reported from that organization’s initial conference in 1960, the students “made it crystal clear that the current sit-ins and other demonstrations are concerned with something much bigger than a hamburger or even a giant-sized Coke. . . . the movement was concerned with the moral implications of racial discrimination for the ‘whole world’ and the ‘Human Race.’”7

Even as the public focused on seemingly narrow demands to end segregation of public schools, lunch counters, and other accommodations in the 1950s and early 1960s, African Americans and Mexican Americans argued that good jobs, open housing, and an end to police brutality were just as essential to their freedom. This line of argument took many forms. African Americans resurrected the “don’t buy where you can’t work” campaigns from the 1930s, most notably in Philadelphia, while demonstrators in Chicago and cities across the North and West boycotted poor, overcrowded schools and fought discrimination in the lucrative construction industry. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. wrote of desegregation meaning little if blacks did not have the money to “buy the goods and pay the fees” that middle-class whites routinely did in Birmingham and elsewhere.8 Even the youth of SNCC, who exercised great caution just to register African Americans to vote in rural Mississippi, used their freedom schools to combat poverty in small ways.

Mexican Americans, disproportionately rural, heavily concentrated in the Southwest, and far from the nation’s political power, did not view their poverty quite the same way as their black counterparts. Yet Mexican Americans shared a similar, overarching goal on which much of their activism focused. Whether it was the American GI Forum or Mexican American Political Association, the Community Service Organization or one of the many other civil rights groups across the country, these organizations combated racial discrimination in order to seek greater economic opportunity for people of Mexican descent. This activism included not only fighting racial discrimination in the schools and other industries but also reducing language barriers to Spanish speakers and electing people of Mexican descent to public office. These actions also took the form of labor organizing, especially of landless farm workers through the California-based National Agricultural Workers Union, the Agricultural Workers Organizing Committee, and eventually the National Farm Workers Association. Many activists—Mexican American, black, and white, including Bert Corona, Pancho Medrano, Bayard Rustin, A. Philip Randolph, and Walter Reuther—sought closer ties between civil rights groups and labor unions in order to empower people economically. Rustin and Randolph, in particular, dreamed of a national civil rights–labor coalition—an objective that remained mostly elusive.

A brief exception, however, was the broad solidarity demonstrated in August 1963, when the demand for jobs and economic justice on a national scale culminated in the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. The event drew an impressive 250,000 people, and while mostly African American and white, there were a handful of Mexican Americans present—two years before any national civil rights organization had reached out formally to people of Mexican descent. The march gained momentum as a lobbying effort in favor of President Kennedy’s relatively narrow civil rights legislation, and is remembered primarily for Martin Luther King Jr.’s “dream.” But jobs and other solutions to black poverty loomed just as large that warm Wednesday in August. The march demonstrated how race and class were intertwined and could be the foundation of a broader civil rights coalition, black, white, and beyond. And within months, long before the civil rights bill passed, the government launched the official War on Poverty.

———

The United States in 1960 was in many ways, as one book famously coined it, an “affluent society.” But just as economist John Kenneth Galbraith had meant by this phrase, the triumphant postwar nation that flaunted an impressive private affluence also risked very little investment in the public sector and often hid substantial poverty. The rapid economic growth of the 1940s and early 1950s had been followed by the “Eisenhower Blues” as the economy slipped into a series of wrenching recessions.9 And the United States’ “semiwelfare state”—reliant on more limited iterations of Social Security and Aid to Families with Dependent Children (AFDC, better known as welfare)—was the thinnest in the Western industrialized world, including the nations that lost World War II. As a result, tens of millions of Americans in 1960 lived in poverty. Estimates of poverty ranged widely and, as Michael Harrington pointed out, basic household income figures often did not reflect variations in region or family makeup and size. Some analyses, such as one conducted by the American Federation of Labor–Congress of Industrial Organizations (AFL-CIO), used the generous cutoff of $4,000 a year for an urban family of four to determine poverty; others such as Galbraith, Senator Paul Douglas of Illinois, and economist Leon Keyserling from President Truman’s Council of Economic Advisors used lower thresholds, from $1,000 to $3,000 a year. But figures from the Census, Bureau of Labor Statistics, U.S. Commerce Department, and the Federal Reserve reinforced an emerging consensus that at least 40 million and perhaps as many as 60 million Americans—out of 180 million, or anywhere from 22 to 33 percent—lived in poverty.10

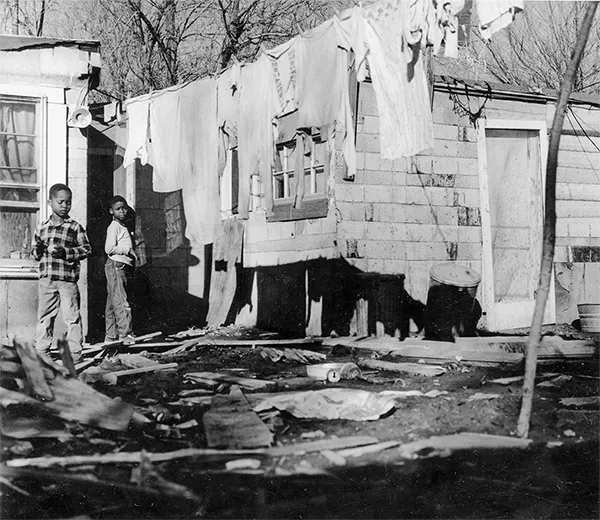

African American children play amid crumbling houses in Barelas, an overwhelmingly poor community one mile south of Albuquerque’s central business district. Largely Mexican American with some black residents, Barelas epitomized the deep poverty of the early 1960s. At 30 percent, New Mexico’s poverty rate was the highest outside of the South; poverty figures for African Americans and Mexican Americans were well over 50 percent. (Albert W. Vogel Photograph Collection [000-005-0023], Center for Southwest Research, University Libraries, University of New Mexico)

No matter how imprecise the definition might be, poverty disproportionately afflicted African Americans and Mexican Americans one hundred years after the end of slavery and the nineteenth-century conquest of the West. At least half of all blacks and one-third of people of Mexican descent lived in what was considered poverty in 1960—compared to roughly 19 percent of whites. And it affected rural and urban alike. For the rural poor, poverty might have meant a family of six or more living in a one- or two-room shack made of tar paper and other scraps with no windows or doors. The children of a sharecropping family in Mississippi would have been lucky to have shoes or to attend the local black school six months out of the year. Post–World War II mechanization of agriculture rapidly diminished the need for sharecropping. But those who stayed in agriculture faced arguably worse conditions as part of the nation’s one million and growing army of migrant farm workers, whether they were black and Puerto Rican migrants working up and down the Atlantic seaboard or Mexican American workers who circulated through the Southwest and Midwest. Families such as the Blakeleys of Belle Glade, Florida, and the Barreras of McCullen, Texas—featured on national television and in Congress—routinely survived on less than $1,000 a year, while they lived in work camps with straw for beds and no indoor plumbing or screens. Water came from a hand pump, and the bathroom was a hole in the ground. And sustained schooling for migrant children was even less common than for sharecropping families.11

In contrast, the urban poor may have had more stable shelter, running water, even working appliances. But living in an impoverished community in Chicago or Los Angeles meant other forms of degradation instead. For instance, in the “second ghetto” of Chicago’s West Side, black families lived in run-down two- and four-flat apartment buildings often infested with roaches and rats in neighborhoods rife with crowded and low-performing schools, few job opportunities, drug use, and petty street crime. Youth gangs became both attractive options for high school dropouts and favored targets for police brutality and harassment. More than 14 percent of African Americans on the West Side were unemployed, with many more underemployed. The average family income was just $2,800 a year—far more than their rural counterparts, but well below the national average, especially for expensive city living. Jobless rates in other cities were even higher; unemployment in south-central Los Angeles, or Watts, topped 30 percent. And in both cities, housing stock available to African Americans declined even as the black population continued to increase. The result was an ever-increasing density that magnified an already grinding poverty.12

Expert explanations for the persistence and size of poverty varied as much as the definitions of poverty did. While the age-old arguments about the Christian work ethic and self-help remained popular among conservative scholars and commentators, new theories also emerged. Some economists, both conservative and liberal, focused on the rise of automation in American industries, which they argued risked creating a permanent class of unemployed within a society of abundance. Calling the situation “paradoxical,” economist Robert Theobald argued, “Because we still believe that the income levels of the vast majority of the population should depend on their ability to continue working, over 20 per cent of the American population is exiled from the abundant economy and this percentage will grow.” Theobald became best known for advocating a guaranteed annual income, or a negative income tax, for “the maintenance of human dignity” of all Americans—a proposal embraced by welfare rights activists later in the decade.13 Others acknowledged such st...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Contents

- Illustrations

- Abbreviations

- Introduction

- 1. The “Rediscovery” of Poverty

- 2. First Experiments

- 3. War, Power, and the New Politics

- 4. Poverty, Peace, and King’s Challenge

- 5. Race and Resurrection City

- 6. Multiracial Efforts, Intra-racial Gains

- 7. The Limits of Coalition

- 8. Making the 1970s

- Epilogue. Poverty, Coalition, and Identity Politics

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Acknowledgments

- Index