eBook - ePub

The End of an Alliance

James F. Byrnes, Roosevelt, Truman, and the Origins of the Cold War

- 303 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The End of an Alliance

James F. Byrnes, Roosevelt, Truman, and the Origins of the Cold War

About this book

Using recently declassified documents, Messer traces Byrnes's performance from the Yalta Conference through the postwar dealings with the Soviet Union. He sees the failure of the Soviet-American collaboration to continue into the postwar years as the result of several unrelated events--the struggle between Byrnes and Truman to become Roosevelt's successor in 1944, Roosevelt's use of Byrnes as his Yalta salesman," and Byrnes's distorted view of the Yalta Conference."

Originally published in 1982.

A UNC Press Enduring Edition -- UNC Press Enduring Editions use the latest in digital technology to make available again books from our distinguished backlist that were previously out of print. These editions are published unaltered from the original, and are presented in affordable paperback formats, bringing readers both historical and cultural value.

Originally published in 1982.

A UNC Press Enduring Edition -- UNC Press Enduring Editions use the latest in digital technology to make available again books from our distinguished backlist that were previously out of print. These editions are published unaltered from the original, and are presented in affordable paperback formats, bringing readers both historical and cultural value.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The End of an Alliance by Robert L. Messer in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & North American History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter One: Introduction

An overflow crowd of well-wishers and the suffocating atmosphere inside the White House on that sweltering afternoon forced the ceremonies outside into the Rose Garden. There, amid the trellised blossoms, cameramen, and microphones, former congressman, senator, Supreme Court justice, and “assistant president” James Francis Byrnes of South Carolina officially became the forty-eighth United States secretary of state. The date was 3 July 1945. The European phase of the greatest war in history had just ended. But its meaning for the postwar world had yet to be resolved. The long and increasingly bloody war in the Pacific was approaching its unexpected, stunning conclusion. Among the throng of government leaders gathered that day at the White House, only a handful besides President Harry S. Truman and his new secretary of state knew of the frantic preparations in New Mexico for the world’s first atomic explosion. It was a time of exhaustion and exhilaration, of intensity and tension, as a partly ravaged, partly exuberant world teetered expectantly on the edge of an unknown future. It was a time of great opportunity and of great responsibility.

Despite the burdens of that responsibility and the oppressive heat, the mood during the swearing-in ceremony was lighthearted. When the oath was completed, Truman said: “Jimmy, kiss the Bible.” Byrnes did so. He then handed the Bible to the president and told him to kiss it. Truman did and the crowd laughed.1 This bit of fun reflects the friendly, egalitarian relationship between the two men. It also suggests the eminence of Byrnes’s position as Truman’s secretary of state. He was not only legally next in line of succession to the president, but he was also prepared to assume the unofficial role as Truman’s “assistant president” for foreign affairs.

Truman had been catapulted into the office of president upon the death of Franklin Roosevelt just eighty-two days before. One of his first decisions had been to make Byrnes his chief foreign-policy adviser as soon as possible. The delayed announcement was the new president’s first major change in the personnel he had inherited from the Roosevelt administration. When, after weeks of press speculation, the appointment was finally made public, it was widely considered to be both a predictable effort toward continuity and a politically prudent gesture of personal reconciliation.

During a war that still seemed far from over, Byrnes had earned the title of Roosevelt’s “assistant president for the homefront.” But for some last-minute maneuvering at the Democratic convention the summer before, Byrnes and not Truman might well have succeeded to the presidency upon Roosevelt’s death. Finally, Roosevelt had chosen Byrnes to accompany him to the last and most important Big Three summit conference at Yalta. There, Byrnes had witnessed firsthand world politics at its highest, most intimate level. Now, on the eve of another Big Three summit, it seemed both logical and wise for Truman to have called Byrnes out of his short-lived retirement from a long and varied career of public service in all three branches of government and turn over to him the conduct of United States international policy at a time when such experience and ability were sorely needed.

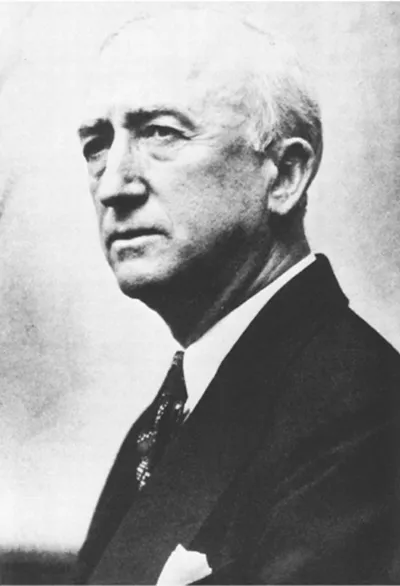

Such was the tone of much of the public comment upon Byrnes’s installation as secretary. However, a contemporary, private commentary is also worth noting. On the same day that Byrnes was sworn in as Truman’s secretary of state, the British ambassador to the United States, Lord Halifax, set down in a report to his government his “appreciation of the personality of Mr. James F. Byrnes . . . together with some comment on the effect which his advent to office is likely to produce on the conduct of United States foreign policy.” This assessment began by noting the facts of his early life and career: his birth in Spartanburg, South Carolina, in 1879 to poor Irish immigrant parents, and his self-made career in law and politics. Halifax compared Byrnes’s rise to the career of his much-admired friend, former Senate colleague, and predecessor as secretary of state, Cordell Hull.

Physically, Byrnes was described as “small in stature with quick observant eyes and a lively face,” a man “richly endowed with characteristic Irish charm.” His “wide fame and popularity” in Washington political circles was attributed in part to “his skill and smoothness as a negotiator on the behalf of the late Mr. Roosevelt to whom he was, until almost the end, very deeply devoted.” As for his weaknesses, he was known for a certain “thinness of skin, sensitiveness to his treatment by others and a need for open tokens of esteem and affection on the part of friends, his colleagues and the public.” Halifax speculated that this sensitivity may have been caused by the fact that Byrnes was “fundamentally unsure of himself, somewhat insecure socially and intellectually.” That insecurity in turn may have resulted from the fact, as Halifax expressed it, that “his background is no less provincial than that of President Truman.”

1. James F. Byrnes at age sixty-six. (Courtesy of the James F. Byrnes Papers, Clemson University Library, Clemson, S.C.)

In comparing the new secretary to the still relatively new president, the ambassador noted that both men were “known to regard the State Department with a highly critical eye and to be irritated by the manner and outlook of the typical departmental career man.” According to Halifax, neither of the two had any use for the “reactionaries and snobs” that inhabited the professional foreign service. However, the two men were unalike in that Byrnes had demonstrated an “eye for ability and [was] not afraid of surrounding himself with clever young men in the best Old New Deal tradition.” This choice of able associates and advisers, in Halifax’s words, “differ[ed] markedly from Mr. Truman.”

As for Byrnes’s approach to his new job, Halifax noted that he prided himself on “his capacity to act as a cautious mediator and conciliator in the most strained and tangled situations.” This “Cavour-like attitude” would most likely cause him to perform as “the ideal pilot, the idealistic honest broker.” Although, as he put it, “the great Roosevelt impetus and its imagination and courage” was no longer there, Halifax looked forward to Byrnes’s improving upon the lackluster performance of the outgoing secretary, Edward Stettinius. Halifax even went so far as to say that it could be “confidently anticipated that the Roosevelt-Hull line in foreign policy would be followed more faithfully under Mr. Byrnes than it was under the somewhat indeterminate direction of Mr. Stettinius.”

But the British diplomat qualified his prediction with what was a prophetic warning. Throughout his analysis of Byrnes’s personality, Halifax cautioned that the new secretary was “occasionally liable to oscillate under strong political pressure” and that he was “temperamentally inclined to follow the lines of least resistance toward public pressure.” Elsewhere in the report, Byrnes was described as “not of strong character, settled convictions, or capacity to fight too hard for them against strong odds.” Although a “very experienced and shrewd negotiator,” he was also “a born politician,” that is, “a person endowed with exceptionally sensitive antennae responsive to the smallest variation of the popular, Congressional, and sectional mood of his country.”2

In typically British understatement, Lord Halifax was trying to say that, if those exceptionally sensitive antennae picked up any variation in the domestic American political mood, Byrnes—and American foreign policy—could change accordingly. One year later, another British diplomat, after observing for some time and at close range Byrnes’s performance as a domestic politician-turned international statesman, confirmed Halifax’s initial assessment in blunter language: “Byrnes is an admirable representative of the U[nited] S[tates], weak when the American public is weak and tough when they are tough.”3

Lord Halifax’s character study is in some ways remarkably insightful, even prescient. It also illustrates the complexity and elusiveness of its subject. Even a shrewd and longtime Washington observer such as Halifax could be wrong about Byrnes.

Although the date 1879 is carved in stone on his grave marker, Byrnes probably was born in 1881.4 Whatever the year, he definitely was born in Charleston, not Spartanburg, though by 1945 the latter place had become his nominal hometown. By no means well off and of Irish descent, Byrnes’s parents (his father died before he was born) were neither first-generation immigrants nor apparently quite so destitute as his log-cabin, Horatio Alger campaign biographies suggest.5

Byrnes’s meteoric rise from local court reporter to district attorney to United States congressman (1911-24), senator (1930-41), Supreme Court justice (1941-42), Roosevelt’s economic stabilizer, director of war mobilization, and unofficial “assistant president for the home-front” (1942-45), and finally Truman’s secretary of state was more varied and spectacular than the career of Cordell Hull. The two southern politicians-turned diplomats were personally close and alike in some ways. But Byrnes accepted the job of secretary of state with the explicit understanding that he would not be just another Cordell Hull—a mere conduit of policies and decisions by a president who was his own secretary of state.

Byrnes unconsciously may have been socially and intellectually insecure. Certainly, to a cosmopolitan British lord, his background, like that of Truman, must have seemed both modest and provincial. Truman at least finished high school. Byrnes was self-educated past the age of fourteen. Although remarkable in its breadth and duration, Byrnes’s career before 1945 was almost exclusively limited to domestic politics. However, outwardly he did not seem concerned or even aware of these limitations. On the contrary, throughout his long line of political successes and in his approach to his job as secretary, Byrnes exhibited a sense of confidence in his abilities, especially when compared to those of Stettinius or Truman, that at times bordered on hubris.

Halifax did not know other things about the new American secretary of state. He could not know of Byrnes’s behind-the-scenes role as Truman’s personal representative on the top-secret committee formed to advise the president on the wartime use and postwar implications of the atomic bomb. He could not know of the unpublicized trips from South Carolina to Washington in the weeks following Roosevelt’s death, of the off-the-record appointments with Truman, of the nighttime briefings at Byrnes’s apartment, of the clandestine meetings with atomic scientists. Until they finally were declassified in 1976 no one other than Truman and Byrnes could know the contents of Byrnes’s top-secret and exclusive stenographic record of Roosevelt’s last summit meeting with Churchill and Stalin at Yalta.

Until recently, historians could only guess why Truman became convinced that only Byrnes could fill the gap in foreign policy left by Roosevelt’s death. New evidence, including the discovery in late 1978 of Truman’s diary for this period, contributes to understanding of an Alice-in-Wonderland relationship in which official or public reality was very often myth. Separating myth from reality is one of the tasks of the historian. But, until now, partly because of the active intervention of the mythmakers, the tools have been inadequate to the task.

If Halifax was a less than perfect witness on some counts, on other matters he was closer to the mark. Like Roosevelt before them, Byrnes and Truman both at first disdained the advice of State Department experts. Byrnes did include in his personal staff talented young men such as the New Deal legal whiz kid Benjamin V. Cohen. Byrnes later came to make an exception to his prejudice against department professionals by relying on the young Russian specialist Charles “Chip” Bohlen. But, rather than necessarily a strength, this reliance on a small circle of handpicked aides eventually isolated Byrnes from his primary and only indispensable source of support, the president. As Truman’s confidence in his own abilities grew, his early dependence upon Byrnes waned. At the same time, the president became more receptive to criticism both of Byrnes’s independent methods and of the substance of his diplomacy.

On the central question of Byrnes’s impact on the course of American foreign policy, Halifax was essentially correct. Byrnes was “a born politican.” He was responsive to variations in the public, the press, and congressional opinion—what could be called the political mood of the country. As the British ambassador’s colleague later pointed out, Byrnes was conciliatory when Americans were in a conciliatory mood. He was also tough when it seemed politically prudent to be tough. Byrnes was not simply an indicator of mass public opinion. His antennae were more sensitive, more sophisticated than that. As an experienced and astute legislative manager, he had spent much of his public life estimating majorities among those who counted. He was alert to the first breath of a change in the domestic political winds.

This study focuses upon Byrnes as an exceptionally sensitive indicator of American political opinion regarding international relations during the onset of the cold war. It reduces that macroscopic process of change in mass perceptions, expectations, goals, and means to the more comprehensible microscopic human scale. Examining the formation, conduct, and dissolution of the Truman-Byrnes partnership as president and secretary of state reveals changes in their lives as well as changes in the larger context of national and international history in which they played such a large part. More accurately, the subject of this investigation is the Byrnes-Truman partnership as “assistant president” for foreign affairs and president. The history of that unofficial partnership does not coincide with the period during which Byrnes officially served as Truman’s secretary of state.

The origins and circumstances of that short-lived but historic unofficial partnership also involves their relationship to a third person: Franklin D. Roosevelt. As Halifax noted in his report, Byrnes had been politically closely associated with and personally very deeply devoted to Roosevelt “until almost the end.” Diplomatically, Halifax did not go into detail about the source of this disaffection. Indeed, he need not have done so. At the time, everyone knew that Byrnes blamed Roosevelt for his unnecessarily humiliating defeat in his bid to become vice-president and Roosevelt’s successor.

The struggle for the 1944 Democratic vice-presidential nomination is one element in the contemporary Roosevelt-Byrnes-Truman relationship. Byrnes’s highly personalized perception of the Yalta conference and his public and private explanation of it to the country and to Truman is another element. In reconstructing that complex, subjective, three-way relationship it becomes clear that, to borrow Halifax’s phrase, Byrnes was a transitional figure between “the great Roosevelt impetus” and the “indeterminate direction” of Truman’s early foreign policy. Byrnes formed a politically sensitive human link between the wartime and postwar presidents and their differing approaches to international relations. As such a link, his living out of the process of change in American-Soviet relations from wartime cooperation to open postwar hostility provides revealing insight into the origins of the cold war. Roosevelt used Byrnes as his “Yalta salesman.” For a time, Truman considered him the “ideal pilot.” When the time for a mediator and conciliator had passed, the pilot was dropped and the cold war began.

Obviously such a reduced focus illuminates only one aspect of one side of a two-sided (and in some ways multi-sided) process. That macroscopic process is interrelated and reciprocal. Scholars do not have and are not likely to have comparable evidence about the inner workings of the Soviet side of the process. In his recent contribution to our understanding of the Soviet side of the cold war, Vojtech Mastny concludes that, though certainly a guilty accomplice, Stalin was also a victim of American inconsistency.6 This study attempts to show that such inconsistency can be explained in part by the Roosevelt-Byrnes-Truman relationship. Such an approach does not provide a total or sufficient explanation of how or why the cold war began. But examining the interaction of three of the key participants in that process provides a new perspective not only on the American half of the origins of the cold war but also on how that half must have appeared to the Soviet leadership.

Perhaps more than anything else, this book reveals how human frailties can influence what is too often portrayed as a totally rational, systemic, or Machiavellian process. The irrational, the petty, the unintended, the vagaries of chance are also part of history. Being reminded of the truism that people make history and that people are fallible should lead not to a smug sense of superior wisdom or morality, but to feelings of sympathy for those who make history and of humility on the part of those who would write it.

Chapter Two: The Struggle for Succession

. . . Byrnes, undoubtedly, was deeply disappointed and hurt. I thought that my calling on him at this time [to become secretary of state upon Roosevelt’s death] might help balance things up.—Harry Truman, 1955

Certainly [Roosevelt] played upon the ambitions of men as an artist would play upon the strings of a musical instrument.—James F. Byrnes, 1966

He had attended every Democratic party national convention since 1912. For the 1944 gathering in Chicago, he had arrived early, fully expecting that this one would be by far the most memorable. It was, but not in the way he had expected. Without waiting for the nomination for vice-president to be officially announced, he left the convention and boarded a train for the return trip to Washington.

As the train eased into Union Station, he could see the Capitol dome gleaming white in the mist and gray clouds. The sight evoked a wistful lament: “I would give all that I own to be back in the United States Senate.” Disappointment, hurt pride, wasted sacrifice, betrayal by a friend, and regret for not having held on to something dear that now was out of his grasp all flowed beneath his words. It might have seemed a curious wish for a man who at that moment hel...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Chapter 1. Introduction

- Chapter 2. The Struggle for Succession

- Chapter 3. The Making of a Myth: Byrnes at Yalta

- Chapter 4. The Selling of a Myth: Byrnes as the Expert on Yalta

- Chapter 5. The Partnership: Byrnes, Truman, and the Bomb

- Chapter 6. Together at the Summit: The Potsdam Conference

- Chapter 7. The First Big Test: The London Council of Foreign Ministers

- Chapter 8. The Decline: Byrnes in Moscow

- Chapter 9. The Fall: Truman Takes Command

- Chapter 10. The Cold War Consensus

- Chapter 11. Man of the Year

- Chapter 12. Et Tu Brute?: Byrnes and Truman in History

- Notes

- Selected List of Sources

- Index