eBook - ePub

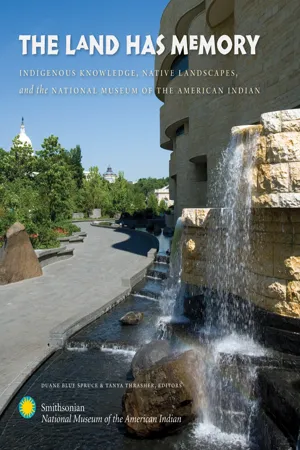

The Land Has Memory

Indigenous Knowledge, Native Landscapes, and the National Museum of the American Indian

- 184 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Land Has Memory

Indigenous Knowledge, Native Landscapes, and the National Museum of the American Indian

About this book

In the heart of Washington, D.C., a centuries-old landscape has come alive in the twenty-first century through a re-creation of the natural environment as the region’s original peoples might have known it. Unlike most landscapes that surround other museums on the National Mall, the natural environment around the Smithsonian’s National Museum of the American Indian (NMAI) is itself a living exhibit, carefully created to reflect indigenous ways of thinking about the land and its uses.

Abundantly illustrated, The Land Has Memory offers beautiful images of the museum’s natural environment in every season as well as the uniquely designed building itself. Essays by Smithsonian staff and others involved in the museum’s creation provide an examination of indigenous peoples' long and varied relationship to the land in the Americas, an account of the museum designers' efforts to reflect traditional knowledge in the creation of individual landscape elements, detailed descriptions of the 150 native plant species used, and an exploration of how the landscape changes seasonally. The Land Has Memory serves not only as an attractive and informative keepsake for museum visitors, but also as a thoughtful representation of how traditional indigenous ways of knowing can be put into practice.

Abundantly illustrated, The Land Has Memory offers beautiful images of the museum’s natural environment in every season as well as the uniquely designed building itself. Essays by Smithsonian staff and others involved in the museum’s creation provide an examination of indigenous peoples' long and varied relationship to the land in the Americas, an account of the museum designers' efforts to reflect traditional knowledge in the creation of individual landscape elements, detailed descriptions of the 150 native plant species used, and an exploration of how the landscape changes seasonally. The Land Has Memory serves not only as an attractive and informative keepsake for museum visitors, but also as a thoughtful representation of how traditional indigenous ways of knowing can be put into practice.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Land Has Memory by Duane Blue Spruce, Tanya Thrasher, Duane Blue Spruce,Tanya Thrasher in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & North American History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

STORIES OF SEEDS AND SOIL

GABRIELLE TAYAC & TANYA THRASHER

All seeds have stories. The evolution of stories, knowledge, and memories of our ancestors are embedded in them. We take care of them like they took care of us. . . . We prepare them for their journey.

Donna House (Diné/ Oneida), 2004

Every plant, animal, and stone has a story to tell. This concept can be understood through the more than 27,000 trees, shrubs, and herbaceous plants; 40 massive boulders; and 4 Cardinal Direction Marker stones placed throughout the National Museum of the American Indian’s landscape. All were carefully selected, blessed with prayer and song, transported over thousands of miles, and thoughtfully re-oriented on the museum’s four-acre site. These living beings traveled by boat, helicopter, flatbed truck, and tractor-trailer, and when they arrived at the museum, they were tearfully and joyfully welcomed as long-absent relatives.

Four hundred years ago, the Chesapeake Bay region abounded in forests, meadows, wetlands, and Algonquian peoples’ croplands. This land, as all of the Americas, can be further understood through indigenous peoples’ cultural perspectives. Over millennia, intense observation and practical experience formed deep knowledge of place. The specific indigenous people of the area now known as Washington, D.C., were called the Anacostans, a tribe belonging to the Algonquian-speaking Piscataway Chiefdom and for whom the Anacostia River is named. The Anacostans did not survive as a distinct people past the first 100 years of English colonization; however, related Algonquian peoples - including the Nanticoke, Piscataway, and Powhatan - maintain a distinct relationship with the land to this day. These peoples gained a deep understanding of the land through observation of the natural world.

In the language of the Algonquian peoples who once lived on this land, wingapo, or “welcome.” Welcome to a Native place.

Entering the museum grounds, visitors immediately encounter the indigenous plants and voices that existed here 400 years ago. The sounds of the city soon fade, replaced by the cacophony of nature: water crashing onto boulders and flowing along the forest’s edge; ducks and birds nesting among the wetlands reeds; and the rustling of tall grasses in the meadow.

This site plan shows the four environments that encircle the museum and a few of the many exterior design features that represent Native peoples’ connection to the land and respect for the Four Directions. The following plant-based information is a synthesis of ideas based on generations of traditional knowledge and practice; under no circumstances should it be considered a guide to the use of herbal medicine.

KEY

1. The northwest entrance features the Grandfather Rocks, birch trees, and a cascading waterfall.

2. Northern Cardinal Direction Marker

3. The museum’s offering area is a place for quiet reflection.

4. Eastern Cardinal Direction Marker

5. Southern Cardinal Direction Marker

6. The south entrance features a spiral moon pattern in the pavement.

7. Western Cardinal Direction Marker

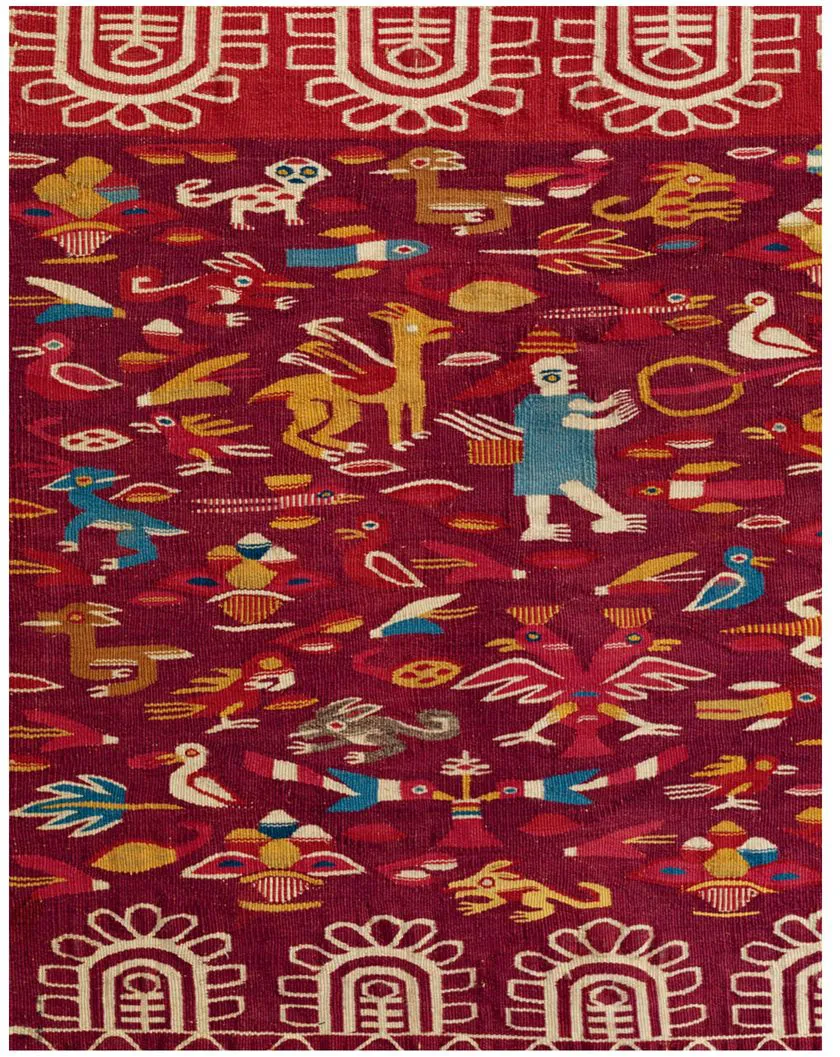

Incan woven manta, Bolivia, 16th c. 5/3773

Although the museum’s diverse plantings specifically recall the indigenous environment and culture of the Algonquian peoples prior to European contact, the four environments are presented with sensitivity to the enduring connections that Native peoples throughout the Americas have to their homelands. Native peoples do not merely adapt to a natural environment but traditionally manage their ecosystem in a way that is consistent with their philosophical worldviews. For example, Native peoples encouraged the growth of a variety of plants in the same area, a technique known as biodiversity. Biodiversity is just one concept that was used to restore the museum grounds to their ancestral form.

The Diné (Navajo) people of the Southwest articulate an idea that profoundly informs NMAI’s landscape and architecture. In the Diné language, hózhó means the restoration of beauty and harmony, which was a guiding principle of Donna House’s landscape-design work at the museum. Rigorous botanical research and numerous consultations with Native peoples went into the effort to bring back the Algonquian environment.

The towering glass doors at the museum’s main entrance - etched with sun symbols - face the east and greet the rising sun, as do many traditional Native homes. Most Native peoples follow a solar calendar, which indicates the proper time to hunt, plant, harvest, and conduct ceremonies. The changing seasons have long been interpreted and honored as a sacred cycle of life, and keen observation of these cycles, especially the solstices and equinoxes, has been considered necessary to ensure the seasons’ continuation.

Through strict observation of nature, Native peoples learned the concept of duality or the balance between two equal states. The duality of nature is reflected throughout the museum grounds, for example in images of the sun and moon at the museum’s main entrances and in male and female plants in each environment. In concert with this concept, most Native societies believe that living on the land involves reciprocity - a process of give-and-take. Humans are generally considered to be responsible stewards of land rather than owners. The Kanaka Maoli (Native Hawaiians) express this idea through the philosophy of aloha ’aina or “love of the land.” Similar to many other Native peoples following ancestral principles, the Kanaka Maoli judge the merit of their actions by whether or not they show proper respect for their environment and compassion for the land.

Goyathlay (Geronimo) with wife and family in melon patch, Fort Sill, Oklahoma, ca. 1895. N37517

Many Native peoples have developed philosophies about the connections between all entities in the universe. Humans are not generally believed to dominate the world in most traditional Native teaching but instead are related to all other beings. The Lakota, for example, affirm their prayers with a phrase that shows their understanding of this idea: mitakuye oyasin, meaning “all my relations.” In many Native languages, non-human beings - either living or inanimate - are referred to in kinship terms. These ideas come from the sacred oral narratives passed on from one generation to the next.

Upland Hardwood Forest

The grouping of trees, plants, and shrubs on the museum’s north side is known as an upland hardwood forest. The more than thirty species of trees reflect the dense forests that exist in the Blue Ridge Mountains, along the Potomac River, and elsewhere. Before European contact, Virginia and Maryland were heavily forested with birch, alder, red maple, beech, oak, witchhazel, and staghorn sumac, among others.

The Nanticoke and other communities relied upon the forest for a variety of foods and medicines, including the willow tree, which was used to create aspirin. Now the most widely used drug in the world, aspirin was made from the tree’s inner bark, which Native peoples boiled or powdered.

The hardwood forest spans the museum’s north side.

Eastern Redcedar

Eastern redcedar is connected to the spiritual traditions of many Native communities, including the Kiowa and Lenape (Delaware). The tree’s unique red, aromatic heartwood and evergreen leaves are valued for ceremonial and medicinal uses. Native peoples make flutes and other items from the beautiful wood, and they burn the tree’s leaves, inhaling the smoke to both purify themselves and help cure head colds.

Native peoples discovered such medicines in many ways, including the observation of animals. For example, they saw that bears rubbed certain plants on their fur, and they learned how to use such plants to treat a variety of human illnesses.

This lush environment is comprised of three distinct types of forest plantings. The three plant communities all require different levels of moisture, ranging from xeric (dry) to mesic (moderate) to hydric (abundant).

Tuliptree, southern magnolia, and dogwood trees provide shade for sumac and cardinal flower in NMAI’s woodlands.

Witchhazel

A popular commercial remedy and facial astringent throughout the world today, witchhazel was first harvested by Native peoples in the eastern United States. The Mohawk, Menominee, Potawatomi, and Mahican tribes used witchhazel as a sedative and as an astringent and valued its ability to stop ble...

Table of contents

- Table of Contents

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Foreword

- Introduction

- HONORING OUR HOSTS - DUANE BLUE SPRUCE

- CARDINAL DIRECTION MARKERS - BRINGING THE FOUR DIRECTIONS TO NMAI

- ALLIES OF THE LAND

- ALWAYS BECOMING

- LANDSCAPE - THROUGH AN INTERIOR VIEW

- STORIES OF SEEDS AND SOIL

- A SEASONAL GUIDE TO THE LIVING LANDSCAPE

- Selected Resources & Organizations

- NMAI Plant List

- Selected Bibliography

- Contributors

- Acknowledgements

- Photo Credits