![]()

The First Generation

That the foundation narrative of one of the original thirteen colonies is so poorly known may seem strange. Two old histories of the proprietary period exist, the first written by Francis Hawks in 1858 and the second penned by Samuel Ashe in 1908.1 Hawks’s history is a quirky collection of documents and stories, organized in a rather idiosyncratic manner. Ashe’s work covers the basic chronology but is short on detail and marred by inevitable errors given the lack of sources employed at the time. Both works have faded from view. Most recent studies skip quickly past the early period of settlement. The latest textbook of colonial North Carolina, for example, devotes far more space to the eighteenth century than to the earliest decades of the colony.2 While studies of colonial South Carolina proliferate, its northern neighbor lies neglected.3

Good reasons underlie the dearth of information. As all historians of the seventeenth-century Atlantic world know, sources do not threaten to overwhelm the archives. We must attempt to put together a jigsaw puzzle with most of the pieces missing, while those that have survived for three hundred years have differential preservation. No completed picture guides the solution. What has made the task even more arduous for historians of North Carolina is the nature of its society in the seventeenth century. The early European settlers were not the kind of people who liked to keep records.4

The treacherous coastline of the Outer Banks, the eerie, inhospitable terrain of the Great Dismal Swamp, and the saga of an Elizabethan colony forever lost offered reasons enough to discourage English settlement of the region south of Virginia for the first half of the seventeenth century. Yet such a place held special appeal for certain people. North Carolina’s first permanent transatlantic inhabitants sought to escape the reach of their masters and governors. They came because of the swamp, not despite it. Imbued with notions of equality and deferential to none, the settlers founded a society on revolutionary principles. To maintain it required secrecy. No one would publish a pamphlet advertising Carolina as a sanctuary for runaways from indentured servitude. Any paperwork might lead to detection by former masters or by debt collectors, perhaps even by tax or tithe collectors. Only land deeds merited the risk of a paper trail. Therefore, almost the entire record base gives the perspective of those who opposed this society. From their papers we must squeeze out the actions and the attitudes embedded in those actions of those closer to the bottom of the social ladder. The volume of documentation does not reflect the importance of these farmers’ role in colonial history. The sanctuary of North Carolina seriously threatened the control of slave and servant so essential to Virginia planter hegemony.

North Carolina’s story fits none of the familiar models of colonial American history. Protestant dissenters came to seek freedom, but this was no City on a Hill. Ex-servants and sailors made it their home, but no port city bustled with politics and commerce. That no city or town of any kind existed for most of the period provides one clue to understanding the society. The lack of a town eased concealing one’s presence from any government inspector, collector, or law enforcement officer whom the proprietors might appoint. It also signifies that the settlers felt no need to fortify themselves against Indians.

The settlers wished to be left alone, but when external authorities tried to seize control and impose taxation, the first generation of settlers, servants, debtors, and dissenters along the rivers flowing into Albemarle Sound continued to wage the English Revolution against the king, lords, and church.

![]()

ESCAPE TO THE SWAMP, 1660 - 1663

America’s southern colonies held forth all kinds of promises to seventeenth-century Europeans: fast money for the younger sons of the aristocracy, religious freedom for the persecuted devout, and escape from the rigors of poverty for the landless. But by 1650, Virginia was a place of possibility only for the already well connected. An aristocracy of rising tobacco planters had emerged, and while the climate and terrain may have looked exotic to an impoverished new arrival from England, the social, economic, and political structures would have felt very familiar. In the Chesapeake, members of the servant class were horribly exploited for their labor, and when their terms of indenture expired, they discovered that all the good fertile bottomland already lay in the hands of the rich few. Those elite families began to turn their attentions to the labor potential of enslaved Africans, increasing their wealth and power over society. Servants and small farmers held little hope of improving their lot.

But to the south, where the Virginians had no political control, lay an area of opportunity. The area was not easily accessible: a huge swamp, already known as the Great Dismal, barred the way. Of course, the planters were developing a sense of entitlement to arable land, and they eventually showed interest in acquiring real estate to the south. The lack of a navigable harbor deterred their settlement, for planters needed a way to ship their staple crops to transatlantic markets. For those with nothing to lose, however, Carolina offered some prospects. In the early 1660s, some seeking an escape from the strictures of hierarchy ventured into the unknown for the chance at a life unbounded by plantation precepts—a “career open to the talents.”

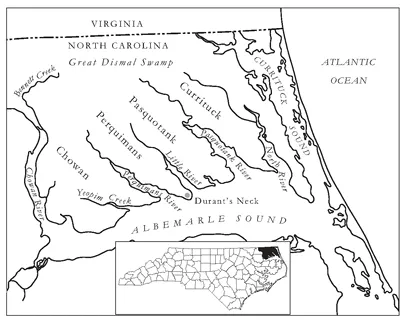

Map 1. Albemarle, 1663-1695

Source: Adapted from Maurice A. Mook, “Algonkian Ethnohistory of Carolina Sound,” Journal of the Washington Academy of Sciences 34, no. 6 ( June 1944): 183.

While unknown Carolina appealed to the vastly different desires of Virginia’s rich, poor, and enslaved, for some people, Carolina was not a dream but a reality. Native Americans, mostly Iroquoian-speaking Tuscarora but also members of many smaller Algonkian-language groups hostile to the Tuscarora, dwelled along the Carolina coast.1 By 1660, they were already familiar with Europeans and Africans, although no large-scale settlements from other continents had been attempted in the region. In the sixteenth century, slaves brought by the Spanish and by Francis Drake to the coast of present-day North Carolina were abandoned to an unknown fate.2 Raleigh’s “Lost Colony” of Roanoke had disappeared by 1590; survivors may have married into or otherwise joined the local population. Traders, both European and Indian, from along the eastern seaboard would also have informed the native North Carolinians about the newcomers and their ways of life. Thus, these Indians had not been entirely protected from the devastation wrought by the diseases carried across the Atlantic by the earliest European and African visitors. Smallpox and measles epidemics followed the traders and took the lives of at least 50 percent of the Native Americans who came into contact with the diseases.3

Most Coastal Plain Indians lived in small villages of perhaps ten households, where the women tended to two small crops of maize, beans, and squash each year, supplementing them seasonally with nuts and berries, while the men hunted and fished in their bountiful surroundings. Hunters, mostly out in the fall and early winter, observed a certain respect for their prey as fellow inhabitants whose spirits must be acknowledged. Indians on the Outer Banks enjoyed oysters and other shellfish, while those further inland used traps and trotlines each spring to catch the spawning sturgeon and herring.4

The mighty Tuscarora, at least eight thousand strong, whose towns and villages lay along the rivers to the south and west of Albemarle, were moving out of self-sufficiency and building strong commercial links with Virginia planters. The trade in pelts and deerskins allowed the Tuscarora to establish their predominance over the region’s smaller Algonkian groups and therefore to view the Europeans as valuable newcomers rather than as a menace as long as the settlements stayed out of Tuscarora hunting grounds.5 The burgeoning fur trade also led to centralization of political authority as some village headmen emerged as organizers of the huge, multivillage, winter hunting drives and presided over business negotiations with the Virginians.6 Not yet entangled in the web of the slave trade, the Indians of northern Carolina stood on that verge and would soon experience its trauma.7

Between 1590 and 1663, circumstances beyond the Spanish presence in Florida stopped official English attempts to acquire native lands in the Carolina region. The lack of a good harbor deterred adventurers. The Outer Banks, the sandbar islands along the coastline, prevented large vessels from docking along the mainland, and the inlets constantly shifted in size and location, rendering mapmaking difficult and offering no confidence to ship captains. An early surveyor from the 1660s noted that “Capt. Whitties vessel this winter at her coming in found fifteene feete water, yet her going out she had but eleaven feete.” The poor captain “struck twice or thrice notwithstanding they had beatoned the Chanell and went out in the best of it, at full sea.”8

The Great Dismal Swamp, south of Virginia, further discouraged potential settlers. It measured twenty-two hundred square miles, constituting a barricade to easy passage for anyone traveling by horse or on foot from Virginia to Carolina. Travelers suffered through a wretched and dreadfully slow, damp, and dreary journey. Even after nearly fifty years of European settlement, the routes through the swamp were not clear. Two of Virginia’s leading gentlemen slogged their way around the area in 1711, trying to establish the border between the two colonies. Their journal gives us a taste of the long and miserable trek through the wet-lands: “In this 6 mile we Crosst several miring branches in which we were all terribly bedaubed . . . Having almost spent the day in this toilsome tho short Journey.” Three days later, they “were well soused in a myery meadow by the way of which we crossed severall.” At certain points they resorted to canoe travel, disembarking two miles from their intended destination and taking a long detour, “there being no firm land nearer.” Another two days into their trip, they recorded that they had “mist our way being wrong directed, and rid 11 mile almost to a myery swamp, almost impassible.” Finding no one available to help them, the two wandering planters, one already suffering from a fever, led their horses “3 mile through a terrible myery Pocoson to a verry great marsh to the River side.” Finally arriving at their lodgings for that night, they reported, “to comfort us we soon found that this little house which was well filled was full of the Itch.” Unaccustomed to such hardships, the gentlemen surrendered their plans, “there being no passage through the Dismall.”9

Their admission of defeat is certainly understandable. Sprawling bald cypress and tupelo gum forests grew in standing water and saturated soils. The giant bald cypress trees measured more than 5 feet in diameter and 120 feet high. Mosquitoes and other biting flies loved the stagnant water and rotting vegetation, but worse awaited the sojourner. Lurking in the dark habitat, poisonous species of cottonmouth moccasins, copperheads, and canebrake rattlesnakes threatened all travelers. Bobcats preyed on human interlopers, and howling wolves terrified the uninitiated. The stench overpowered the senses.10

The Dismal Swamp comprised a mixed set of terrains, most of them difficult to navigate. Pocosins, or bays, housed evergreen shrub bogs. These waterlogged soils, capable of sustaining only low-growing shrubs, lay relatively open. However, plant life included a variety of briers and dense stands of cane, all exceedingly difficult to penetrate. Somewhat drier soils in the swamp gave birth to large Atlantic white cedar forests, yet even these soils remained wet enough to impede travel. One of the few welcome geographic features for the traveler in the swamp was the hammock. Slightly elevated landforms that contained several species of oak as well as beech and tulip poplar, hammocks were navigable even on horseback. But these small natural features were scattered only randomly throughout the swamp. While travel on foot or horseback was exceedingly difficult, sustained travel on water proved almost impossible: although the vast majority of the swamp stayed saturated year-round, almost no waterways were navigable. Thus, all swamp travelers shared the Virginians’ frustrations.11

Gentlemen might be reluctant to dismount and dredge their way through the swamp, but others willingly took the challenge. For those who wished to escape the rigors of indentured servitude and slavery in plantation Virginia, the Dismal Swamp was more of a beacon than a barrier. The tobacco boom in Virginia created a massive demand for labor but did not lead to better working conditions for those who toiled in the Chesapeake. The numbers of servants, mostly young single men, crossing the Atlantic under indenture peaked during the Interregnum period. Long, hard days in the humid tobacco fields came as a physical shock to the English, used to the cool summers of home. Masters had license to whip their servants, contracts were freely bought and sold, and the courts furnished little recourse for injustice—the planters controlled the legal system. Those schooled in Cromwell’s Leveller Army did not take what they felt to be a violation of their rights lying down. Two separate groups of Virginia servants unsuccessfully plotted rebellion in the early 1660s, one in York County, the other in Gloucester. “Several mutinous and rebellious Oliverian Soldiers” led the Gloucester insurrection. 12 The York rebellion was also believed to be headed by ex-Cromwell men. 13

Not only was servitude brutal, but little hope of reward accompanied the end of one’s term. No automatic grant of land awaited Virginia’s ex-servants, and the land grab by the larger planters in the first half of the seventeenth century had left limited opportunities for the newly freed to sustain themselves. By the 1660s, “landownership for poor whites had become a dubious possibility.”14 Enough of those still indentured freed themselves by escaping that Virginia passed a 1660 law that sought to break the bonds between servants and slaves who ran away together. English servants who ran off “in company with any negroes” were to have their terms of indenture extended not just to make up for their own lost work time but also to compensate owners for the loss of the labor of their slaves, who were already bound for life.15 For a few brave or desperate souls, therefore, Carolina presented a strong temptation.

Another group joined the runaways escaping bondage and those seeking free land. Quakers in America, like those in England, had come under attack in the early 1660s. The Quakers were viewed as politically dangerous in America as well as England, not only by Cavalier aristocrats such as Virginia’s governor, William Berkeley, but also by Puritans, who were prepared to kill Quakers rather than risk having their ideas spread through Massachusetts. Persecution in Maryland and Virginia was as intense as colonial officials could muster, given the difficulties of policing in rural areas. The Virginia Assembly passed the Act for Suppressing the Quakers in 1660, and in August of that year, Berkeley scolded the sheriff of Lower Norfolk County, the area of Virginia bordering on Carolina, for failing to enforce the measure more rigorously: “I hear with sorrow that you are very remiss ...