![]()

1 Preservation Comes of Age

![]()

Chapter One

Some Preservation Fundamentals

Robert E. Stipe

The context of preservation has greatly changed over the last half century. Like the editors and contributors to With Heritage So Rich forty years ago,1 we are faced with a host of new issues, as well as some old ones. Like its predecessor, this book is biased toward traditional values, but it also represents an attempt to deal with the preservation issues of our own day as a new century beckons. The prologue to this book poses a question, “why preserve?,” that is still unasked and unanswered for a majority of the public. We thus must confront a major public educational task, one even greater and more complex than in 1966. How we approach that task and how well we succeed in completing it depends, first, on how well we understand the larger context of preservation as an emerging phenomenon in America.

Changing Values

Preservation’s basic values have vastly changed since 1966. The early associative values centered almost exclusively on history and architecture as the most valued cultural resources. In recent years, however, we have moved beyond that narrow view. For example, National Register Criterion A (“the broad patterns of our history”) has in most states become as important as style and design in architecture, and archaeology is a prominent value in the western states. A wide variety of specialized resources such as battlefields, designed and vernacular landscapes, mines, recent buildings, entire inner-city neighborhoods, and vernacular buildings are now widely accepted, as are a broad range of newly popular resources: highway commercial “strip business” developments, early filling stations, ships, lighthouses, outstanding contemporary buildings, and post–World War II subdivisions. Racial, tribal, and ethnic interests are firmly embedded in our preservation programs, and many would agree that such intangible cultural values as music, dialect, and storytelling should be added to the mix. American Indian tribes now have a special role in preservation programs, in recognition of their status as sovereign nation-states, and as the world grows smaller, the local traditions and preservation techniques of one nation seem to migrate ever more quickly to others. Monuments and sites of special international importance to all of humankind are threatened or lost as a result of war, neglect, or the march of progress, and the international dimension of preservation takes on a special significance. Cultural homogenization has become an issue.

The Preservation System

At first glance, the American historic preservation system seems terribly complex. However, in broad outline it is not, provided one has a solid understanding of three basic concepts. The first and perhaps most important is the general structure of the American federal system of government. The second is the universal nature of the preservation-conservation process itself. And the third is the nature of our free market economic system. To deal effectively with preservation problems, one must first be able to comprehend all three of these basic phenomena. The remaining sections of this chapter consider these fundamental concepts.

The Structure of Government

The first aspect of preservation in America that must be understood is our three-tiered, federal-state-local system of government. Most Americans—and most preservationists—neither appreciate nor fully grasp this system. Each of the three layers of government confronts us with both incentives and obstacles to historic preservation, and it is an unusual preservation situation that does not, in some manner, involve all three.

At the federal level, some of the obstacles we face are embedded in our Constitution, which is almost impossible to change or amend, as well as in congressional mandates and bureaucratic regulations and attitudes, which are also changed only with difficulty. The same is true at the state level, except that each of the fifty states has its own constitution, legislation, and traditions of governing and preservation problem solving. Thousands of local governments with their own ways of doing things add to the complexity of the problem. At all of these levels there will be the politics of the situation, the relative political strength of the contestants themselves, and the bureaucracies and institutions representing them. This usually presents the most difficult hurdle that preservation and other environmental interests must overcome.

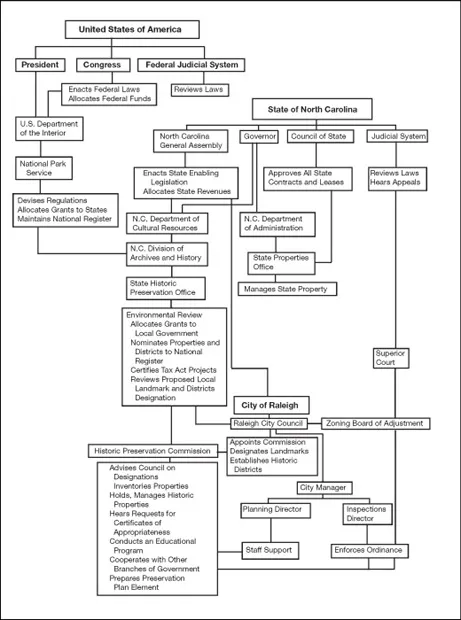

Organization of preservation responsibilities in North Carolina. This diagram dramatically illustrates the complexity of our layered, interconnected system of federal, state, and local governments involved in historic preservation, each with its own executive, legislative, and judicial system. Although it outlines how preservation functions in North Carolina, similar but equally complex relationships exist in all other states. Understanding these relationships is the starting point to effective participation in historic preservation activities. (Linda Harris Edmisten and Robert E. Stipe)

The starting point in sorting all of this out is to ask: What is government? It helps to think of governments as “sovereign” and “derivative.” A sovereign government is one that has certain basic powers: to tax its citizens and spend the proceeds; to regulate the personal conduct of its citizens and the way they use their land; and to acquire, own, manage, and dispose of property for public purposes—taking or “condemning” that land from unwilling citizens if necessary for public use on payment of fair compensation.

Unfortunately, most citizens think of the federal or national government as the most important, because it is in Washington, D.C., or because it is “above” the others, and because it has access to almost unimaginable wealth. But in fact, it is not our basic government, nor even a “sovereign” government as just described. Our federal or national government was created by the states in the Constitution of 1787 and is thus a derivative government in the sense that it can exercise only those powers granted to it by the states in that document, such as the power to declare war, coin money, and deliver the mail; make treaties with other countries; create an army; regulate interstate commerce; and the like.

This narrow view is sometimes referred to as the “old” federalism. But Article 1, Section 8, of the Constitution also gives Congress unspecified, general power to pass legislation for the “general welfare,” a power that over the years has, it is argued, enabled the federal government to embrace additional functions not specifically mentioned. This more liberal approach is often referred to as the “new” federalism. How far it extends is frequently the subject of lively debate.

What is important to remember, however, is that the states did not give away all their sovereign or inherent power to the federal government when they created it. They retained for themselves, in Amendments 9 and 10 to the Constitution, the basic power to regulate citizens in their personal conduct and the use of their property. This retained power is called the “police power,” and it includes the power to regulate historic buildings.

This bit of history notwithstanding, there are indeed a lot of federal regulations pertaining to preservation and many other matters. But if there is no inherent federal regulatory authority, as just noted, what are these federal regulations? In short, federal regulations pertaining to historic preservation, the use of land, and hundreds of other activities are, in effect, a ritual form of bribery, mostly enacted under the “new” federalism of Article 1, Section 8, of the Constitution, which also gives Congress the authority to levy taxes and provide for the general welfare. Much of the federal government’s so-called regulatory authority thus derives from the fact that Washington has tremendous wealth derived from personal and corporate income taxes, which it may “give back” to state and local governments with strings attached—strings adopted in general by Congress and later detailed by federal agencies. These are commonly called “federal regulations” and are found in the Code of Federal Regulations (CFR), which is cited in various places in this book.

Cartoon: “I Want You!” How should a committed preservationist react to a statement like the one implied in this editorial page cartoon? Most of us would probably accept some of the federal activities shown as quite proper and reject others. Overall, however, the cartoon intones the widely held, conservative bias of many who believe that the “old” federalism would probably exclude federal involvement in activities like historic preservation. (Gary Brookins, Richmond [Va.] Times-Dispatch)

Since all federal aid is subject to conditions set in Washington, federal regulations are a kind of string on loans, grants, and other forms of assistance from the national government. If they are violated, they result only in the potential loss of assistance to carry out federal programs in accordance with national policies—for instance, historic preservation, highways, housing, hospitals, schools, welfare, airports, libraries, parks, education, and just about everything else done or built by state and local governments. These days little happens that is not done in part with federal money or is not subject to a federal permit. Thus, disregarding federal policies or failing to abide by federal regulations means losing federal “aid”; this creates political problems at the state and local levels, like raising taxes to make up the loss or forgoing programs that citizens want.

Under our system, the truly sovereign or primary unit of government is, in fact, the state. After all, it was the states that got together and created a national government of thirteen states, now fifty in number, and they continue to hold all the basic powers not specifically given to the federal government in the Constitution of 1787 and its amendments. Of particular importance to preservation is that the states retained the “police power,” or the power to regulate citizens’ personal behavior (assault, murder, swearing in public, stealing, etc.) and the use of property (zoning, historic districts, landmark designation, building codes, etc.).

Cities, like the federal government, are created by the states and are also derivative governments. And though the states, as sovereign governments, have not delegated the police power “up” to Washington, they can and have delegated much of their regulatory authority “down” to cities and counties. (Counties, historically speaking, are local branches of state government spread over larger geographic areas to better provide state services locally—such as schools, law enforcement, care of the poor, roads, running the courts, holding elections, keeping real estate records, and other functions). The governmental powers delegated “down” to cities are somewhat different than those of counties in that they center on the needs of citizens living closely together: water and sewer services, police and fire protection, recreation programs, libraries, and so forth. These include land-use regulations like the creation of historic districts and the designation of landmarks, enforcement of subdivision and zoning ordinances, and other growth management measures. Today, in addition to their traditional responsibilities, many counties have been given the same powers as cities and have therefore also assumed responsibilities that involve historic preservation.

All of this explains how it is that local governments can simultaneously embrace nonregulatory National Register historic districts or buildings, designated by the U.S. Department of the Interior, and at the same time adopt and enforce local historic district and landmark ordinances passed by the city or county government under its state-delegated regulatory or police power over the same property. It also explains why National Register property owners are generally free to do whatever they want to their buildings so long as no federal money, permit, or other federal program is involved. But if those same property owners also hold property in a local historic district, or live in a designated landmark established by the local government pursuant to the sovereign police power of the state, they can be jailed or fined for violating a local historic district or landmark ordinance. As it works, a single historic property can be in one district and not the other, or the other and not the one—or both.

This may sound like a lot of theory, but in application it is very, very real. It is imperative that this underlying theory be understood, because the failure of most citizens, politicians, and administrators to comprehend these distinctions creates more problems for preservation than any other cause.

The Preservation Process

The second basic concept to understand is that from a procedural standpoint, preserving old buildings or neighborhoods is fundamentally no different from preserving a threatened or endangered animal or plant species, a coral reef, or the scenic character of a rural landscape. Conceptually, as well as at a practical level, the sequential steps are, first, setting standards or criteria that define what is worth preserving; second, undertaking a survey to locate and describe resources potentially to be saved; third, evaluating the resources discovered in the survey against the standards established in step one; fourth, giving those that qualify “official status” in some way; and fifth, following up with protective measures. These five steps are always involved and follow exactly that sequence in preserving anything—whether a mountain trail, the endangered Red Cockaded Woodpecker, or an old building. The objects or resources to be preserved or protected may be different, but the process itself never changes. Understanding the purpose and sequence of these steps, and why each step must be done correctly, is essential.

In our system, a basic standard of what is worth preserving is articulated in the various criteria established by the National Register of Historic Places in some instances, but state or local criteria may also come into play in others. Notwithstanding that new associative values—townscapes, vernacular and designed landscapes, marine resources, ethnic and racial history, and others—have crept into the system since 1966, architecture and history are still regarded by many as the bedrock associative values. In practice, most of our standards are derived from earlier, narrower views about what is worth preserving. Thus is maintained a tradition that extends back to the mid-1930s, when a New Deal, depression-era program, the Historic American Buildings Survey, was created to put unemployed architects back to work. Although the National Register standards are heavily weighted in favor of traditional thinking about architecture as art and history as a series of events, new words like “culture” and “histor...