eBook - ePub

The Column of Marcus Aurelius

The Genesis and Meaning of a Roman Imperial Monument

- 264 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

One of the most important monuments of Imperial Rome and at the same time one of the most poorly understood, the Column of Marcus Aurelius has long stood in the shadow of the Column of Trajan. In The Column of Marcus Aurelius, Martin Beckmann makes a thorough study of the form, content, and meaning of this infrequently studied monument. Beckmann employs a new approach to the column, one that focuses on the process of its creation and construction, to uncover the cultural significance of the column to the Romans of the late second century A.D. Using clues from ancient sources and from the monument itself, this book traces the creative process step by step from the first decision to build the monument through the processes of planning and construction to the final carving of the column’s relief decoration. The conclusions challenge many of the widely held assumptions about the value of the column’s 700-foot-long frieze as a historical source. By reconstructing the creative process of the column’s sculpture, Beckmann opens up numerous new paths of analysis not only to the Column of Marcus Aurelius but also to Roman imperial art and architecture in general.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Column of Marcus Aurelius by Martin Beckmann in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & History of Architecture. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

chapter one

THE DATE & PURPOSE OF THE COLUMN

At the end of the second century A.D., in the early years of the reign of the emperor Septimius Severus, a Roman official named Adrastus—a former slave but now a freedman of the emperor—moved into a new house. Adrastus was not just any official, and his was not just any house. He was the procurator or caretaker of the Column of Marcus Aurelius, and his new residence was built just behind the column. The remains of his house were found in the year 1777 during excavations beneath the Piazza di Montecitorio, about one hundred meters to the west of the Piazza Colona and the column itself.1 We know a lot about Adrastus’s house because he recorded its construction in a pair of remarkable inscriptions, dating to the year 193, that reproduce letters that Adrastus exchanged with the emperor and his servants.2 The letters were inscribed on a tall marble block that formed the doorpost to the new house (fig. 1.1). In the first letter, Adrastus asked for official permission to replace the little hut, cannaba, in which he had heretofore been living, with a more substantial dwelling, described as a hospitium. Since he knew the area well, Adrastus also suggested a specific location for his new house, a certain distance “behind the hundred-foot column of the divine Marcus and Faustina, on public ground” (post colu[mnam centenariam divorum] Marci et Faustina[e . . . loco publico] pedibus plus min[us] . . .). In reply, Adrastus was not only given permission to build his new hospitium, but also to pass it on to his heirs.

But Adrastus got even more: in one of the letters, three imperial treasury officials instruct another administrator to assign to Adrastus “all the bricks and building materials” (tegulas omnes et inpensam) “from the little houses, huts and suitable buildings” (de casulis item cannabis et aedificiis idoneis).3 The location of these little houses, huts, and buildings is not specified, but because no other specific details are given, it must be assumed that they would have been known to Adrastus. They presumably were located near the cannaba, or hut, that Adrastus wanted to replace with his new hospitium. Adrastus was explicitly permitted to build his hospitium in the place

FIGURE 1.1. Inscription of Adrastus (copy in Museo della Civiltà Romana, Rome). Photo by author.

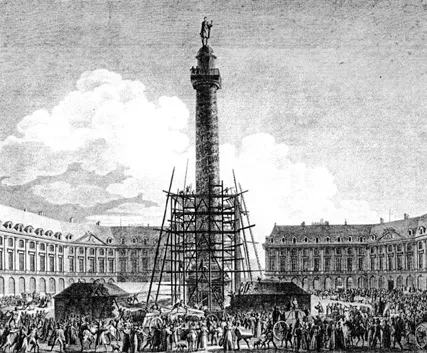

FIGURE 1.2. The Colonne de la Grande Armée, Paris, during demolition of surrounding workshops just after its completion in 1810. Bibliothèque nationale de France.

where his hut already stood (loco cannabae), a certain distance behind the Column of Marcus Aurelius. The “little houses, huts and suitable buildings” mentioned in the letter therefore likely stood near the column too. A sensible conclusion is that they were temporary structures of various sizes that had been built to act as storerooms, workshops, and perhaps even barracks during the construction of the column itself. An impression of what these structures may have looked like is given by an etching of the Colonne de la Grande Armée on Place Vendôme in Paris (fig. 1.2). The column, still partly surrounded by scaffolding, stands in the middle of a small courtyard formed by brick buildings, which are in the process of being torn down. The timbers are being collected and the bricks taken away in carts. A similar situation can be imagined at the conclusion of work on the Column of Marcus Aurelius. If Adrastus was being given permission to cannibalize the materials of service buildings to construct his own house, then their useful life was over and their purpose—to support the construction of the Column of Marcus Aurelius—was complete. Therefore it seems more or less certain that the column was completed in the year 193.

Unfortunately the date of completion is much less helpful for our understanding of the column than the date of its decree. This is the single most important unresolved question about the Column of Marcus Aurelius, and a difficult one to solve, because the evidence is by no means clear. There are two main contenders: 180, the date of the death of Marcus Aurelius and the ascension of his son Commodus; and 176, when Marcus returned to Rome after a multiyear absence and celebrated a triumph for his German and Sarmatian victories.

In the late nineteenth century, both dates were considered equally possible, but since then the trend has been toward accepting a date of 180, thus attributing the decision to Commodus.4 This is no more than a four-year difference, but the identification of the proper date could hardly be of greater importance. At stake is our understanding of the fundamental function of the monument: is it primarily funerary (A.D. 180), or is it primarily honorary (A.D. 176)? In the inscription of Adrastus, the column is called columna divi Marci, “the column of the deified Marcus,” suggesting on the face of things that its primary purpose was to honor the emperor after he had died and been deified. But unfortunately this is not as helpful as it may at first seem. At the time when the inscription was made, the year 193, Marcus Aurelius was thirteen years dead and long-since deified. Thus any reference at that time to a monument to Marcus could have called him a divus, regardless of whether the monument was set up during his lifetime or posthumously. By way of comparison, the Column of Trajan was certainly commissioned and completed during that emperor’s lifetime, but was also known as “the Column of the deified Trajan” after his death.

There are no other preserved inscriptions (the pedestal of the column surely carried one, but it was removed after antiquity and before the earliest modern drawing was made), and textual sources of any sort are few and far between. The most-often quoted is a problematic reference in the text of a fourth-century writer of abbreviated imperial biographies, Sextus Aurelius Victor. Concerning the events after Marcus’s death, Victor wrote: denique, qui, seiuncti in aliis, patres ac vulgus soli omnia decrevere, templa columnas sacerdotes (Liber de Caesaribus, 16.15): “then, the Senate and the People, who in the cases of other emperors acted independently, decreed everything together, temples and columns and priests.” At first glance, this reference seems to give evidence that the Column of Marcus Aurelius was erected in his honor and after his demise by decree of the Senate and people of Rome. But there are problems. The main question is, what are we to understand by the plural noun columnas? What is Victor referring to? Does he mean that Marcus Aurelius was honored by the column we know today, in addition to an unspecified number of others?

This numerical ambiguity is only one of the problems with Victor. Also dubious are his qualifications as an expert on Roman topography and his overall accuracy. Sextus Aurelius Victor was born in North Africa, around A.D. 320.5 He moved from North Africa to Rome, where he served, perhaps, as a bookkeeper in the imperial service. He then moved to Sirmium, where he was (again, perhaps) fiscal secretary to the praetorian prefect; later he was made governor of Pannonia by the emperor Julian. At Sirmium, between about 358 and 360, he wrote his Liber de Caesaribus. Victor’s position as urban prefect of Rome is sometimes appealed to as an argument in support of the accuracy of his statements about the city—but he did not take on this office until 388, a quarter of a century after his wrote his history.6 Thus Victor had some experience in Rome but wrote his imperial history in a city far away from the capital. He would have relied, presumably, on memory for any details of Roman topography, and had no opportunity to check the facts for himself. He could not have visited the column in person, and thus he could not have read its inscription and confirmed its date of dedication even if he had wanted to. Also problematic is Victor’s record of inaccuracy. His work is full of errors and misunderstandings. For our period he records, for example, that Marcus Aurelius gave citizenship to all the inhabitants of the Roman empire, when in fact this happened much later, under Caracalla.7 Victor also reports that Commodus was made Caesar on the death of Verus, but in fact Verus died in 169, and Commodus had already been made Caesar in 166.8 The latter error might be forgiven, the result presumably of an assumption that when Verus had died, Marcus would have immediately wanted a colleague to fill his shoes. The former is more serious—but it too has a likely explanation, which I will return to later in this chapter. For now it is enough to say that Victor’s reference to columnas in the Liber de Caesaribus, a poor source in general, cannot be taken with any degree of confidence as evidence for the date of the Column of Marcus Aurelius.

This exhausts our literary sources. The next-best evidence for the date of the column comes from the monument itself, or more precisely from the content of its relief decoration.

Visual Evidence: Dating the Frieze

In the absence of solid written evidence for the date of the decision to build the Column of Marcus Aurelius, most scholars have turned to its sculpture. Two elements of the relief decoration of the column are potentially useful as dating tools: clearly historical scenes in the frieze, and the presence or absence of Commodus in the overall decoration. The rationale behind each is simple: if it were possible to determine what time period is represented by the images on the column, whether the main helical frieze or the pedestal relief, it would be possible to use this to help date the monument. The basic argument for using the frieze to date the column is this: if the events shown on it only cover the period up to 175, then a date of 176 would be highly likely. If however the relief shows events from the campaigns down to 180, that would support a postmortem dating for the monument. Crucial here is the presence or absence of Commodus: if Commodus is certainly absent from the column’s decoration, this would be a strong argument for a date of 176 (before Commodus became directly involved in his father’s wars), but if his image can be shown to have existed anywhere in the relief decoration, this would be a near-certain guarantee of a date of 180.

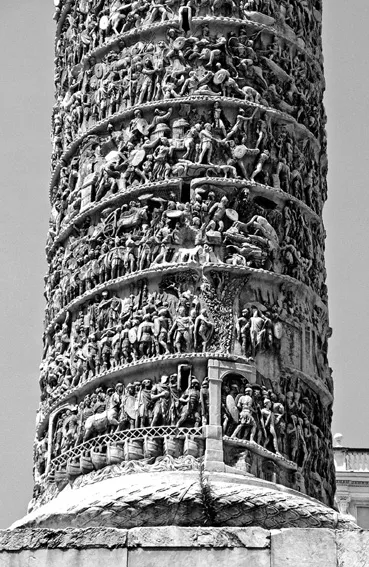

In the main helical frieze, three scenes above all others are generally thought to be historical—that is, to represent specific historical events: the Danube Crossing at the base of the column; the Victoria in the middle; and the Rain Miracle, located between the two. Figure 1.3 shows the lowest of these scenes, the Danube Crossing and the Rain Miracle, as they appear from the perspective of a viewer standing at the base of the column today (the ancient view would have been more distant, as the ground level has since risen by approximately three meters—see chapters 2 and 9). Marcus Aurelius and his troops certainly crossed the Danube at the beginning of the war, and must have done so at other, later times during the course of various campaigns during the 170s. But there is no specific characteristic of this scene that allows us to decide when the crossing depicted took place, except for its appearance at the start of the frieze, which would seem to suggest a date sometime at the beginning of the campaigns. The Victoria, on the other hand, does not represent in a realistic fashion a particular event in the wars, but rather alludes to victory through a personification. Marcus

FIGURE 1.3. Lower portion of the column, seen from the east. In the first winding, Marcus crosses the Danube on a boat bridge; in the third is the Rain Miracle. Photo by author.

Aurelius celebrated two victories during the 170s: one over the Germans in 172, the other over the Sarmatians in 175. Both are commemorated on coins and led to Marcus being titled Germanicus and Sarmaticus. The general trend has been to interpret the Victoria as representing Marcus’s first victory and thus serving as a divider between his two main campaigns, just as the Victoria on Trajan’s Column stands between that emperor’s two Dacian wars.

The Rain Miracle, unlike the Danube Crossing and the Victoria scenes, definitely represents a specific historical event. Records are preserved in a number of sources, including the work of the historian Dio (see the detailed discussion of the scene in chapter 7), that tell the story of how a Roman army was saved from thirst and barbarian attack by a lightning storm and a torrential downpour. We even have an apparently reliable date for the event: Dio says that as a result of this victory Marcus was saluted imperator by the troops for the seventh time; this title first appears on coins marked as struck during his eighteenth tenure of the tribunician power and thus dating to the year 174.9 This creates a problem: if the Danube Crossing was intended to represent an event that occurred in 170 or 171, and the Victoria an event that occurred in 172, then the Rain Miracle is very much out of place in a supposedly chronologically organized frieze.

A number of solutions to this problem have been put forward, most involving detailed arguments for the redating of one or more of the Danube Crossing, Victoria, or Rain Miracle scenes.10 The most convincing solution, however, is this: that the content of the frieze is not a strictly chronological account of the wars of Marcus Aurelius. The strongest evidence in favor of such an interpretation is to be found in the Danube Crossing and Victoria scenes themselves. At first glance, they seem to be there because they commemorate specific events in Marcus’s campaigns. But this is in fact not the case. These two scenes, so often taken as chronologically fixed points, are in fact copied from the Column of Trajan (the Danube Crossing in particular is an exact copy of the corresponding scene on Trajan’s column—see chapter 5). This connection is usually ignored, and even in the rare cases where it is acknowledged (for example by Wolff with regard to the Victoria), it is most often simply assumed that these scenes still must have a specific historical meaning on Marcus’s Column.11 There is no sound reason for such an assumption to be made, and the evidence of the strong parallels in the details of these scenes between the two columns speaks strongly against it. The Danube and Victoria scenes may well have brought to mind for the viewer events in Marcus’s campaigns (the emperor and his army did cross the Danube, and Marcus did win victories), but the fact that they are copied from Trajan’s Column, and copied in exactly the same positions and precisely in a number of details, indicates that the act of copying, not any historical relevance, is the reason for their presence and, most important, for their exact positioning on the column. Thus they have no value as specific historical evidence for events in Marcus’s wars.

Further evidence of the nonhistoric nature of the Victoria in the frieze of the Column of Marcus Aurelius can be found in its setting within the column’s narrative, by which I mean the nature of the various scene...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- THE COLUMN OF MARCUS AURELIUS

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- INTRODUCTION

- chapter one THE DATE & PURPOSE OF THE COLUMN

- chapter two THE DUST OF NORTHERN WARFARE: Choice of Location

- chapter three FORM & FUNCTION

- chapter four PLANNING & CONSTRUCTION

- chapter five THE FRIEZE: Concept & Draft

- chapter six CARVING THE FRIEZE

- chapter seven THE FRIEZE AS HISTORY

- chapter eight THE FRIEZE AS ART

- chapter nine VIEWING THE COLUMN

- epilogue THE COLUMNS OF TRAJAN, MARCUS AURELIUS, & ARCADIUS

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index