![]()

CHAPTER ONE

Gold, God, Race, and Slaves

Slavery in the Americas was justified by racist ideology. Many scholars as well as the wider public believe that black Africans were enslaved because they were viewed by whites as inferiors. But the identification of race with slavery is largely a projection backward in time of beliefs and ideologies that intensified during the four centuries of the Atlantic slave trade, the direct European occupation and colonization of Africa during the late nineteenth century and into the second half of the twentieth, and the brutal exploitation of Africa’s labor and natural resources ever since.

Before the Atlantic slave trade began, racism justifying slavery in medieval Spain and Portugal was aimed at people with light skin. Although there were some enslaved blacks there, slave status was identified with whites. The very word “slave” is derived from “Slav”: whites who were captured in Eastern Europe and shipped into medieval Spain in large numbers. Racist ideology was based on climatic determinism, but it was the Slavs who were considered natural slaves. A scholar who lived in Spain during the eleventh century wrote:

All the peoples of this category who have not cultivated the sciences are more like animals than men.... They live very far from southern countries ... in glacial temperatures with cloudy skies.... As a result, their temperament has become indifferent and their moods crude; their stomachs have become enlarged, their skins pale and their hair long. The finesse of their minds, the perspicacity of their intelligence is null. Ignorance and indolence dominate them. Absence of judgment and grossness are general among them. Thus are the Slavs, the Bulgarians, and neighboring peoples.1

In medieval Spain and Portugal, dark-skinned people were often identified as conquerors and rulers rather than as slaves. The Islamic conquest of Spain began in 711 under Arab leadership. The Moorish conquest began in 1085. Moors ruled in the Iberian Peninsula for almost 400 years before the Atlantic slave trade began. The trans-Saharan trade linking sub-Saharan Africa with the Mediterranean world predated the birth of Islam. Pure, unadulterated gold arrived via the ancient camel caravan trade across the Sahara Desert. The purity and reliable weight of the coins minted in medieval Spain stimulated trade throughout the Mediterranean world. D. T. Niane has written:

In the tenth century the king of Ghana was, in the eyes of Ibn Hawķal, “the richest sovereign on earth ... he possesses great wealth and reserves the gold that have been extracted since early times to the advantage of former kings and his own.” In the Sudan it was a long-standing tradition to hoard gold, whereas in Ghana the king held a monopoly over the nuggets of gold found in the mines: “If gold nuggets are discovered in the country’s mines, the king reserves them for himself and leaves the gold dust for his subjects. If he did not do this, gold would become very plentiful and would fall in value ... The king is said to possess a nugget as big as a large stone.” However, the Sudanese always kept the Arabs in the most complete ignorance regarding the location of the gold mines and how they were worked.

Salt, silver, copper, and kola nuts were also used as trading currencies. Ivory, skins, onyx, leather, and grain were important export items. The black slaves exported were mainly female domestics in demand by the Berber Arab aristocracy. Niane states that the numbers of black male slaves exported in medieval times for labor across the Sahara to Egypt and the Mediterranean has been exaggerated.2

As the Reconquest advanced, the Iberian Christian kingdoms sought to bypass the trans-Saharan trade controlled by the Moors, sail down the West African coast, and exploit the sub-Saharan gold deposits directly. Rather than slaves, gold was the main concern of the Portuguese rulers, merchants, and explorers who first sailed down the Atlantic coast of West Africa. Black slaves, initially a byproduct of the search for gold, became an increasing source of wealth in the Iberian Christian kingdoms.

The Senegal River Valley had deep, sustained economic, technological, cultural, religious, and political ties with Spain and Portugal. These contacts began very early. Jewish trading communities in sub-Saharan West Africa evidently preceded Islam. As early as the eighth and ninth centuries, Arab chronicles report Jewish farmers in the Tendirma region on the Niger River. A Portuguese chronicle dating from the early sixteenth century speaks of very rich but oppressed “Jews” in Walata.3

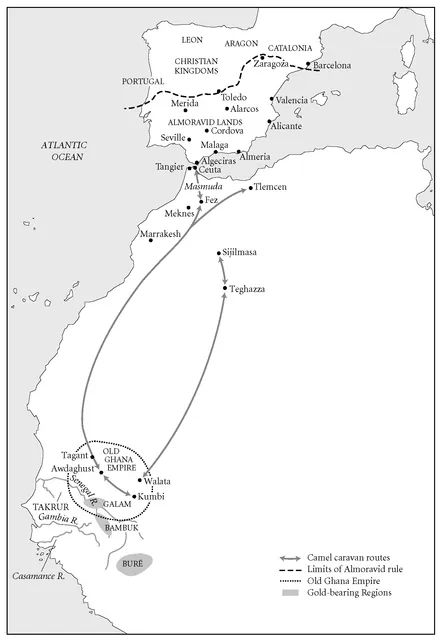

The Almoravids, a puritanical religious movement, were the first Islamic conquerors in sub-Saharan Africa. Established by Ibn Yasin among the Sanhaja Berbers, they moved south across the Sahara Desert to control the gold trade of Galam and the gold mines of Bambuk and Buré along the upper Senegal River. Wardjabi, king of Takrur, was an early convert. He and his son Labi allied themselves with the Almoravids and began to attack Godala, king of Ghana, in 1056. They captured Koumbi Saleh, the capital of the ancient kingdom of Ghana, in 1076. The kingdom of Takrur then controlled the Senegal River and its basin and monopolized the famous gold trade of Galam. The Almoravids had almost simultaneously moved north across the Sahara, founded Marrakech, and established their capital there in about 1060. In Spain, Toledo fell to the Christians in 1085. The Islamic Taïfa kingdoms had allowed the Christians to advance by intriguing and fighting among themselves. They invited the Almoravids in to protect them. The Almoravids defeated the Christians, withdrew, and then were reinvited in after the Taïfa kingdoms had failed again to stop the Christian advance. This time the Almoravids remained as rulers. By 1090, they had taken back much of the Iberian Peninsula from the Christians, stopped the gold payments made to the Christian kingdoms by the Taïfas, and created the first Moorish dynasty in Spain. This dynasty merged Western Islam into a huge state stretching from the Senegal River Valley, Mauritania and the western Sudan, Morocco, and most of what is now Spain and Portugal.

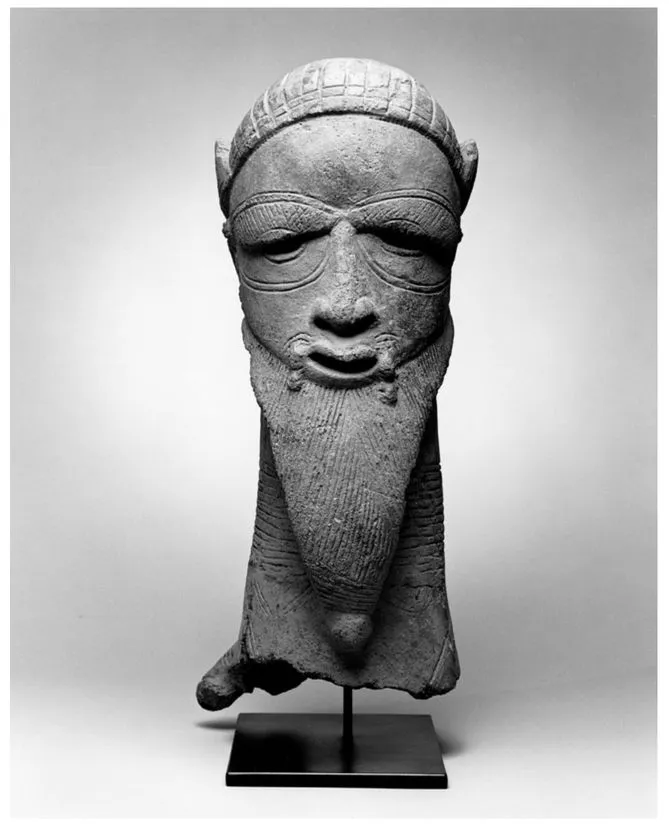

Nok-Sokoto Culture, Nigeria, “Head of Court Figure,” terra cotta, ca. 300 B.c.-A.D. 200. This piece is among the oldest sculptures found in sub-Saharan West Africa. (New Orleans Museum of Art: Gift of Mrs. Françoise Billion Richardson, 95.357.)

Thus four centuries before the Atlantic slave trade began, black Africans from the Senegal region were quite familiar in the Iberian Peninsula. Many dark-skinned peoples appeared in the late eleventh century not as slaves but as warriors, conquerors, rulers, bards, and musicians. In paintings portraying meetings and negotiations among Christians and Moors during the Spanish Reconquest, the Moorish generals, negotiators, and rulers were often portrayed as blacks.4 The Almoravids recruited black mercenaries as soldiers. In Seville during the first half of the twelfth century, officials tried to make distinctions between the Almoravids rulers and their black mercenary troops, requiring them to wear masks (abid ) different from those worn by the Almoravids rulers (litam).5

The rule of the Almoravids in Spain was given an unjustifiably bad reputation by two nineteenth-century Northern European historians: Philip K. Hitte and Reinhart Dozy.

6 These eminent founders of the European history of the Islamic world did not escape from the intense, overt racism of their times. They sometimes relied uncritically on sources of questionable objectivity. Resentful apologists for the Taïfa Kingdoms wrote some of these sources. Other sources derived from apologists for the Almohads Dynasty, which overthrew the Almoravids. The Almoravids are rarely discussed in history, and when they are, their bad reputation persists. Nevertheless, they were highly praised by their contemporaries and by Spanish historians, some of whom have proudly proclaimed that Africa began at the Pyrenees.

7 Some Spanish historians have emphasized the unacknowledged debt Renaissance Europe owed to Moorish Spain. In 1899, Francisco Codera, citing an early chronicle in Arabic, argued against racist interpretations of the Almoravids’ rule in Spain. The chronicler wrote:

The Almoravids were a country people, religious and honest.... Their reign was tranquil, and was untroubled by any revolt, either in the cities, or in the countryside.... Their days were happy, prosperous, and tranquil, and during their time, abundant and cheap goods were such that for a half-ducat, one could have four loads of flour, and the other grains were neither bought nor sold. There was no tribute, no tax, or contribution for the government except the charity tax and the tithe. Prosperity constantly grew; the population rose, and everyone could freely attend to their own affairs. Their reign was free of deceit, fraud, and revolt, and they were loved by everyone.

Map i.i. Almoravid Dynasty, 1090-1146. Adapted from maps by O. Saidi and P. Ndiaye, in UNESCO General History of Africa, vol. 4, ed. D. T. Niane, and vol. 5, ed. B. A. Ogot (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1984 and 1992); copyright © 1984 and 1992 UNESCO.

Even after its overthrow, other chroniclers of Islamic Spain praised the rule of the Almoravids. They wrote that learning was cherished, literacy was widespread, scholars were subsidized, capital punishment was abolished, and their gold coins were so pure and of such reliable weight that they assured prosperity and stimulated trade throughout the Mediterranean world. Christians and Jews were tolerated within their realms. When the Christians rose up in revolt, they were not executed but were exiled to Morocco instead. The Almoravids were criticized, however, for being excessively influenced by their women.8

When the Moors ruled Western Islam, a great variety of trade goods passed abundantly within this vast region. Horses and cattle, hides, leather goods, skins, dried fruits, arts and crafts, tools, swords and other weapons, ivory, onyx, grain, gold, silver, copper, precious gems, textiles, tapestries, pottery, salt, and kola nuts were widely traded. The coins of the Almoravids were minted mainly from gold coming from Galam in the upper Senegal River, which arrived via long-established camel caravan routes across the Sahara. Knowledge as well as technology moved across the Sahara in all directions.9 Al-ŝaqudi (d. 1231/32) identified nineteen musical instruments including the guitar found throughout Western Islam. He attributed the origin of most of these instruments to pre-Moorish Islamic Spain. The accuracy of this attribution should not be taken at face value. His book was a defense and glorification of pre-Moorish Spain.10 Music is, of course, the most transportable cultural feature because it speaks a nonverbal, universal language. Musical style, musical instruments, and systems of musical notation traveled freely back and forth across the Sahara. Some Renaissance and post-Renaissance European music, including notation of pitch and rhythm, probably was transmitted from Moorish Spain.11 Alonso de Sandoval, a Jesuit missionary working in Cartagena de Indias during the first half of the seventeenth century, wrote that the Guineans taught the Spanish and Portuguese a famous dance called “Canarios.” 12 Transculturation of music and dance throughout Greater Senegambia, Northwest Africa, Spain, Portugal, and thence to the Americas is an open question. The origins and directions of this flow of music remain to be studied. Rhythm, singing, dance, and musical instruments demonstrate cross-culturation across the Sahara in all directions. This ancient cradle of music might help explain the universal appeal of jazz as well as what is now called World Music.

Iberian languages contain substantial vocabulary derived from Arabic words for law, administration, public offices, military and naval terms and ranks, architecture, irrigation, manufacturing, and other technologies. Spain exported principles of the Spanish Reconquest to the Americas. During its early stages, the pope justified the Atlantic slave trade as an extension of the Reconquest to sub-Saharan Africa and gave Portugal a monopoly of the maritime trade there. Christian beliefs, laws, and practices in Spain and Portugal were deeply influenced by Islamic concepts of international law, the rights and privileges of the conqueror and the conquered, the justification for enslavement, the law of slavery, and the mutual obligations and rights of masters and slaves. The concepts of just war and legal enslavement, including limitations on the right to enslave coreligionists, stemmed largely from Islamic law. Discussions about legal enslavement in early America involved mainly the mutable concept of religion rather than the immutable concept of race. When African slavery was introduced into the English colonies in the Americas during the seventeenth century, Christianity, not race, continued to dominate discussions of legal slavery, just enslavement, and whether enslaved Africans who converted to Christianity had to be freed. The link between religion and race centering on the curse of Ham played a minor role in these early discussions.13 Racist justifications for enslavement and slavery of black Africans increased over time.

Despite the relative fluidity of color prejudice in medieval Spain and Portugal, as the Atlantic slave trade developed, slavery became associated with blacks, and antiblack racism became very powerful in Portuguese and Spanish America. Although its forms were different, racism was just as strong as in other American colonies. Corporatism was the foundation of law. The corporatist legal system was based on inequality before the law. It made legal and social distinctions among groups of people denned in accordance with comparative amounts of white blood among mixed-bloods and how many generations they were removed from slavery. Thus important distinctions were made among nonwhites, creating conflicts among them. It was a very efficient mechanism of social control for societies where the Spanish and Portuguese were a small minority ruling and exploiting a large subaltern population. It enabled the Iberian elite to exercise more effective control over all of the social layers beneath them. Thus some white blood in the lower casts carried much more weight in Latin America than it did in the British colonies. In insecure frontier societies like Spanish Florida and Louisiana and elsewhere in Latin America, military and police use of slaves and their descendants was promoted as a strategic policy. Manumission of slaves was encouraged to expand the layer of protection enjoyed by Spanish colonists and rulers against their own subjects as well as against foreign threats.14 These more privileged, militarized population sectors were expected to keep order, chase runaway slaves, and serve as militias during the frequent wars among the European colonizers of the Americas. Purity of blood, pureza de sangre, was highly valued among the Latin American elite, although its Native American and African antecedents can sometimes be documented. Antiblack racism was and remains very powerful in Latin America. Some scholars from the United States, impressed by these formal contrasts with racism in their own country, have spread still widely believed myths of mild slavery and benign race relations in Latin America, making it much harder to combat racism because its existence is often denied.15

Not enough has changed since W. E. B. Du Bois lamented the state of denial and the high level of rationalization among historians of the Atlantic slave trade and slavery in the Americas. Some eminent historians are still excusing and rationalizing it, and their ideas are spreading in Europe and even in Africa. One popular argument is that slavery was widespread in Africa before the Atlantic slave trade began and that Africans participated in this trade on an equal basis with Europeans. Many “Western” historians deny that European and American wealth and power was built up to a great extent from the Atlantic slave trade and the unpaid labor of Africans and their descendants in the Americas.

Slave trade and slavery existed throughout the world for millennia. But it was not the same in all times and places. Slavery is a historical—not a sociological —category. The transatlantic slave trade was uniquely devastating. It was surely the most vicious, longest-lasting example of human brutality and exploitation in history. It was an intrusive, mobile, maritime activity carried out by faraway powers insulated from retaliation in kind. For over 400 years, it involved the hemorrhaging of the most productive and potentially productive age groups among the population in African regions deeply affected by it.16

Why was it Africans who were enslaved and dragged to the Americas to fulfill the colonists’ needs for labor? Why did Europeans victimize Africans instead of sending their own people or other Europeans to the Americas either as voluntary immigrants or fo...