eBook - ePub

The Color of Christ

The Son of God and the Saga of Race in America

- 352 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

How is it that in America the image of Jesus Christ has been used both to justify the atrocities of white supremacy and to inspire the righteousness of civil rights crusades? In The Color of Christ, Edward J. Blum and Paul Harvey weave a tapestry of American dreams and visions — from witch hunts to web pages, Harlem to Hollywood, slave cabins to South Park, Mormon revelations to Indian reservations — to show how Americans remade the Son of God visually time and again into a sacred symbol of their greatest aspirations, deepest terrors, and mightiest strivings for racial power and justice.

The Color of Christ uncovers how, in a country founded by Puritans who destroyed depictions of Jesus, Americans came to believe in the whiteness of Christ. Some envisioned a white Christ who would sanctify the exploitation of Native Americans and African Americans and bless imperial expansion. Many others gazed at a messiah, not necessarily white, who was willing and able to confront white supremacy. The color of Christ still symbolizes America’s most combustible divisions, revealing the power and malleability of race and religion from colonial times to the presidency of Barack Obama.

The Color of Christ uncovers how, in a country founded by Puritans who destroyed depictions of Jesus, Americans came to believe in the whiteness of Christ. Some envisioned a white Christ who would sanctify the exploitation of Native Americans and African Americans and bless imperial expansion. Many others gazed at a messiah, not necessarily white, who was willing and able to confront white supremacy. The color of Christ still symbolizes America’s most combustible divisions, revealing the power and malleability of race and religion from colonial times to the presidency of Barack Obama.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Color of Christ by Edward J. Blum,Paul Harvey in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Theology & Religion & Christianity. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART ONE

BORN ACROSS THE SEA

CHAPTER ONE

WHEN CHRIST CROSSED THE ATLANTIC

Tituba had seen more than most. An enslaved woman purchased in Barbados and perhaps originally from South America, she found herself in the middle of an uproar in the small colonial village of Salem, Massachusetts. Her owner, Samuel Parris, was born in England and ventured to the New World as a boy. After Harvard, he became a cantankerous Puritan minister who complained as much about his lack of firewood as he did about the sins of the world. In the early 1690s, he seemed obsessed with the devil. “There are devils as well as saints in Christ’s church,” Parris exclaimed in one sermon. Then he located evil in the heart of their community: “If ever there were witches, men & women in covenant with the devil, here are multitudes in New England. . . . Now hundreds . . . are discovered in one shire.”1

Tituba was terrified when the devil first appeared to her, or at least that is what she told the court in 1692 when summoned to speak. He demanded that she worship him and instructed her to hurt the children of the village. After pinching her skin and pulling her hair, he tempted her with “pretty things.” When the court asked her who the devil was now using to harm Salem’s children, the Indian slave who possessed so much spiritual sight cried out, “I am blind now, I cannot see.”2

There was nothing out of the ordinary for Tituba—or for any Native American, slave, or Puritan—to claim to perceive sacred forces working around them. Colonists lived in an enchanted world where lightning, rainbows, and bumps in the night could be rendered as acts of God or designs of the devil. What was strange in Salem was that authorities looked to Tituba for help. Salem had been bedeviled, and their outpost community was spinning out of control. Children accused elders; women accused men; slaves claimed spiritual vision; and political, religious, and judicial leaders asked them for supernatural guidance. Sacred fears reverberated so widely and so intensely that by the end of the season more than twenty colonists had been executed or had died in prison. Tituba, however, was not one of them.3

The devil was everywhere in Salem, and he could take any number of physical forms. One witnessed him as a “little black bearded man.” Another saw him as “a black thing of a considerable bigness,” and yet another beheld a black dog to be Satan. The devil came as a Jew and as a Native American as well. But we need not be fooled—the devil did not always come in blackness or redness. Sarah Bibber saw “a little man like a minister with a black coat on and he pinched me by the arm and bid me to go along with him.” The devil could corrupt, seduce, and use the bodies and souls of British colonists, their children, and many others.4

Jesus seemed absent amid the madness. Ann Putnam narrated a frightful tale in which the forces of evil were hell-bent on her destruction. She went before the court to denounce Martha Corey and Rebecca Nurse for being in league with the devil. Putnam remembered lying down one day in March when suddenly the spirit of Martha Corey tortured her. Corey’s apparition demanded that Putnam sign her name in a little red book—the devil’s book of death. According to Putnam, “No tongue can express” the “Hellish temptations” she endured. Then, and even worse, Rebecca Nurse’s spirit came and spewed hate against God and “blasphemously denied . . . the power of the Lord Jesus Christ to save my soul.”5

Where was the savior in all this? Court proceedings never mentioned Tituba seeing him; Ann Putnam said nothing of him swooping in to save her from torment. Of all the dozens examined, only one claimed to encounter Christ. Sarah Bridges met a man who said his name was Jesus. Perhaps the Son of God had come to battle the devil, and Salem’s faithful would witness the final showdown of Armageddon prophesied in the Book of Revelation. Alas, even this man turned out to be the devil in disguise. Satan was so sacrilegious that he even tried to pose as Christ through a possessed body.6

This was the state of sacred vision and the body of Jesus in the colonial world that would become the United States. While slave and free, male and female, young and old professed under oath to interact with demonic forces, none was immediately saved by the Son of God. While the devil used physical costumes aplenty as he tried to lead away Salem’s sheep, the good shepherd made no corporeal appearance. Jesus was worshiped as a savior. He was preached as a power. But for Puritans, he was physically absent.

There were no dominant images of Jesus in early colonial America. Spanish and French Catholics, along with their Indian converts, represented Jesus visually, but in a variety of forms. And throughout North America, destroying images of Christ was just as important as displaying them. This was an age marked by destructive iconoclasm. Actively not seeing Jesus by reducing icons to rubble or by excluding images of him from churches defined the era as much as those moments where he was brought across the sea. Throughout the seventeenth century, New World struggles did not revolve around what Christ’s body looked like, but whether he should be embodied at all.

Jesus was neither white, nor red, nor black, and all types of people could interact with him. Colonial America was a raucous world where western Europeans, Native Americans, and West Africans (each group with countless differences among themselves) fought, loved, and prayed. Christ was brought into all sorts of discussions and interactions. He was an object of colonialism and confusion, and in the dynamic moments of cross-cultural exchange, he was transformed. In turn, ideas about him remade the many players as they interacted.7

A variety of factors account for the relative absence, unimportance, and even annihilation of Christ’s physical body in the British colonies. Few of the groups involved had any inclination to create an image of the divine, and few had the manufacturing or distributing abilities to create a prevailing representation. The newness of Native American encounters with Jesus, the lack of freedom and diverse associations between color and divinity among West African slaves, and the radical iconoclasm of the English settlers created an eastern North America where no physical representation of Jesus dominated the landscape.

The white Jesus of European artwork was not a natural import to what would become the United States. For the British Protestants who would control much of America, a white Jesus sanctified neither the white people as sacred because of their whiteness nor the place as holy because of its Americanness.

Whiteness was not made sacred in the form of Jesus, in part, because whiteness itself as a marker of racial identity and power did not yet exist. Loyalties of nation, region, tribe, and religion outweighed other conceptions of identity and muddied the waters of allegiance. Labor demands made any person exploitable. Anywhere from one-half to two-thirds of the first British immigrants were transported against their will. Most were unfree laborers. Moreover, the first English colonists encountered many commanding and skilled Native Americans, while their entry into the West African slave trade was contingent upon powerful African tribes being willing to trade them slaves. English colonists inhabited a world with so many differences of language, faith, and power that they rarely spoke, thought, or wrote in generalized claims of race and racial difference. Concepts of racial hierarchy or white supremacy could not be mapped onto Christ’s body, because the racial lexicon and worldview of whiteness had not yet been created.8

The lack of a dominant image allowed Jesus to be an active and malleable part of cultural exchange, dialogue, and dissension. He was an unstable symbol in this environment, easily configured and reconfigured by various groups to speak to their changing conditions. The iconographic emptiness would be filled later with a white Jesus, but that conflation of racial supremacy with spiritual identity would be made in the future. Tituba’s time was too uncertain and unstable—so uncertain and unstable, in fact, that she, a slave, saved herself in Salem by speaking authoritatively about visions of the devil, not his divine destroyer.

Native First Encounters

Most Americans place the “beginning” of their history with the colonies at Jamestown in 1607 and, two decades later, the Pilgrims and the Puritans in New England. From there, the adventure marches westward in a grand narrative of sweeping expansion across an empty paradise. But the history of Jesus in the lands that would become the United States offers a very different story. Jesus came to Santa Fe, St. Augustine, and Iroqouia before he washed ashore in Virginia or New England. The English used his name in the West African slave trade a full generation before Jamestown was planted. In disparate places, French Jesuits, Spanish Franciscans, English Puritans, Anglicans, grizzled soldiers, diverse Native Americans, and manacled West Africans mixed and matched with each other, killed and saved each other, and in the process created brand-new worlds.

As they swapped spit and stories, their germs and their gods came into contact and created new religious forms. Jesus came with Europeans—but was then transported in time, space, and memory across social, cultural, and linguistic borders. He was a part of New World conquest and contact but was then elemental to new cultural formations and expectations. For the Native Americans who lived along the northern East Coast, their first encounters with Jesus were momentous. Sometimes they embraced him. Oftentimes they rejected him. But as the decades moved on and the Europeans kept coming, they could not ignore him.

When Europeans arrived in the Americas, they confronted a religious diversity of epic proportions. Each tribe seemed to have its own spirits, its own origin tales, and its own reckoning of the sacred. And none of them spoke Spanish, French, or English. Europeans found Indian beliefs frustratingly ambiguous. They were couched in stories and dreams. They constantly seemed to shift from one informant to another. Of course, many natives felt the same about the diverse Catholic and Protestant faiths brought to them by people who looked and sounded different and told strange tales of a killed and resurrected God-man. Most Indian religions were about right practice, not right belief; they emphasized the practical nature of a plurality of spirits, not right doctrine about one triune deity.

From the eastern coast of North America to the western sierras of New Mexico, Jesus was a potent symbol of colonial encounters. He became in Indian country as diverse as the tribes that encountered him. At times, he appeared as a practical diviner showing the way to the animals. Other times, he served as a symbol of colonial power targeted for desecration. He could also be a new divine presence whose physical suffering spoke to their human struggles. Often natives transformed Jesus into a Manitou, a god spirit that could take various forms, interact with humans, and provide them with special powers.

Spanish Catholics were obsessed with carrying Christ to the New World. Christopher Columbus gave himself the title “Christoferens” (Christ-bearer) and believed more strongly over time that his expeditions were marked by God to bring faith to the heathens. Throughout Central, South, and North America, conquistadores and Franciscan priests marched with swords, crosses, and images of Christ in tow. They destroyed indigenous icons and replaced them with images of Jesus—a Christ who usually had brown hair flowing at least beneath his ears and perhaps down his back, brown eyes, and darkened white skin. By the middle of the sixteenth century, Jesus began popping up miraculously among the natives. Mexico’s Cristo Aparecido was perhaps the most fascinating. “Christ Appeared” first revealed himself to Spanish authorities in the Mexican village of Totolapan in 1543. Carved from the maguey, a plant native to Mexico, and having a green cross against his back, this Christ was less than three feet long. His creation was shrouded in mystery, supposedly delivered to the convent of Totolapan in the arms of an Indian stranger. It has survived as the patron of residents to the present day, in the intervening centuries becoming known for powers of healing and veneration. Similar images migrated to New Spain’s northern frontier, where Franciscans (as in California) hoped to fashion a Christ-centered spirituality in the New World.9

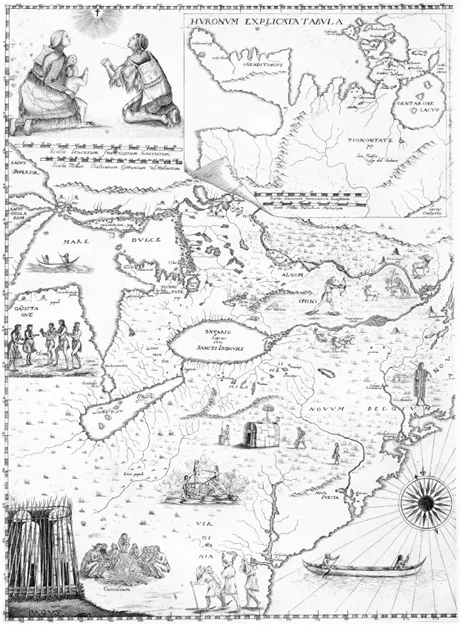

When Jesus came to eastern North America, he moved furthest inland with French Jesuits. They established mission outposts in the Great Lakes region and later near the Mississippi River from Illinois to Louisiana. Rather than conquer, these missionaries tried to join native communities. The Society of Jesus detailed their adventures in seventy hefty volumes of missionary fund-raising propaganda now called The Jesuit Relations. The works bristled with Jesus as a figure of conquest, contact, and transformation. The Jesuits saw themselves, their mission, and French overseas imperialism happening under the figurative and literal image of Jesus. According to one chronicler of the Jesuits celebrating their arrival to Canada, “The figure of Christ, covered with a canopy, was carried about with the greatest possible ceremony, and he came auspiciously into the possession, so to speak of the happy land.” As a material object that was part of the long history of Catholic iconography and a new figure for French adventure, this Jesus oversaw the European possession of the land and proclaimed it good.10

Conflict and cultural collision came with Christ. The Jesuits encountered natives who were confused by Jesus, and their questions about this man-god showed concerns about relationships among body, spirit, geographical presence, and tribal loyalties. Was he just another holy spirit? Had he walked with the natives on their soil in the past? Could he help them locate animals in the present, and if so at what price? Could he cure disease, or was there something for their souls beyond their pox-marked flesh? As the Jesuits observed, the natives wanted to know exactly how this Jesus fit within their worlds.

For some, Christ was a problem because he had never appeared in North America. “Your God has not come to our country, and that is why we do not believe in him,” one native told Father Paul Le Jeune. The Frenchman responded that Jesus could be seen with “spiritual” sight, but this did not satisfy the native. “I see nothing except with the eyes of the body, save in sleeping,” he explained, “and you do not approve our dreams.” Perhaps pointing out Le Jeune’s hypocrisy in trusting his own stories and dreams but not those of the natives, this Indian believed that any reasonable supreme God would appear to all, not just to some.11

Others feared Jesus. Some considered both the Jesuits and their savior to be sorcerers (or “jugglers,” as the Jesuits often called them). Sorcerers were ambivalent tricksters for many Indians. They were able to offer guidance but also to take life. “I hardly ever see any of them die who does not think he has been bewitched,” noted Father Le Jeune, and the shamans were believed to have done the bewitching. Would Jesus or the Jesuits do the same? Others found the French Catholic visual representations ominous. Paintings of Christ and the Madonna in new chapels purportedly possessed magical qualities. The pictures could supposedly cast illness onto anyone who gazed at them.12

Novae Franciae accurata delineatio (1657), western portion. Courtesy of the Li...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- THE COLOR OF CHRIST

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- CONTENTS

- ILLUSTRATIONS

- PROLOGUE

- INTRODUCTION THE HOLY FACE OF RACE

- PART ONE BORN ACROSS THE SEA

- PART TWO CRUCIFIED AND RESURRECTED

- PART THREE ASCENDED AND STILL ASCENDING

- EPILOGUE JESUS JOKES

- ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

- NOTES

- INDEX