![]()

[1]

The Champion of the Darker Races

Japanese torpedo boats struck the Russian naval base at Port Arthur on the evening of 8 February 1904, inflicting heavy damage and closing the entrance to the harbor. The Russians were caught by surprise. The entire battle lasted less than an hour. Although the Japanese attack came without a declaration of war, both countries had previously taken bold steps to protect their rival claims in Korea and Manchuria, including the issuance of an ultimatum from Tokyo. Japanese nationals were evacuated from Port Arthur several days before the attack and diplomatic relations were severed on 6 February. As the struggle for mastery in northeastern Asia shifted to land warfare, the Russians anticipated an easy victory over the Japanese, whom they derided as “monkeys.” Once again Japanese military prowess surprised the Russians, but neither side found victory as easily as they hoped. Port Arthur did not fall to the Japanese until January 1905. The Japanese took Mukden, in central Manchuria, later that winter. They suffered heavy casualties in both campaigns and seemed ready to negotiate an end to the war rather than face a large Russian army still intact in northern Manchuria. The fighting continued, however, as both sides hoped that gains on the battlefield would improve their position at the peace table. The Russians placed their hopes on a climatic naval battle that would destroy Japan’s recently won naval supremacy and break its line of communications with the mainland. Instead, the tsar’s Baltic Fleet sailed halfway around the world and directly into the Japanese line of fire in the Straits of Tsushima on 27 May. Within hours the Russian armada was devastated. The next day the Russians surrendered the remnants of their fleet.1

The significance of Japan’s victory was immediately grasped in distant places. When Alfred Zimmern, a lecturer at Oxford University, learned of Japan’s victory, he promptly shelved his talk on Greek history and spoke to his students about the “most important event which has happened, or is likely to happen, in our lifetime; the victory of a non-white people over a white people.”2 In Capetown, South Africa, not far from where thousands of Chinese workers labored in the gold fields, a European lecturer warned his audience that Japan’s success had awakened in China a movement of “China for the Chinese.” He hoped that it would not also be “South Africa for the Chinese.”3

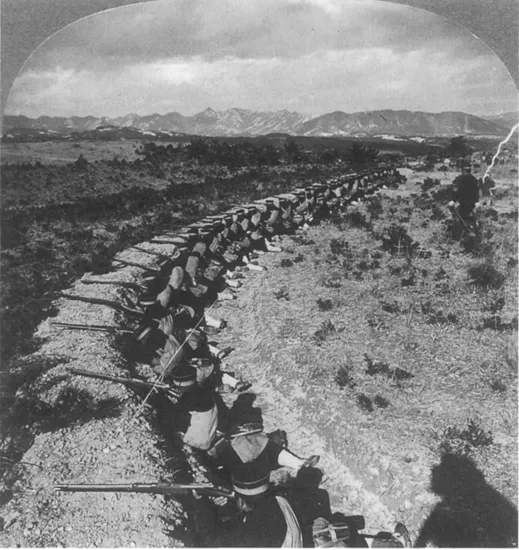

Japanese soldiers holding the line in Manchuria after firing the shots heard around the nonwhite world, ca. 1905–6.

(Photograph by Standard Scenic Company; Library of Congress)

Many black Americans saw the outcome of the war as a matter of great significance to their own lives. According to eminent African American scholar W. E. B. Du Bois, Japan’s stirring victories broke the “foolish modern magic of the word ‘white’” and raised the specter of a “colored revolt against white exploitation.”4 The news of Japan’s victory reached a black American public that was already attentive to world affairs and attuned to viewing events from the perspective of the world’s subject peoples. In the decade before the Japanese navy stunned the white world by destroying the tsar’s Pacific and Baltic fleets, African Americans had begun to display a renewed interest in world events. During that time the resurgence of European and American imperialism in Africa, the Middle East, and Asia elicited the attention of educated black citizens. As Lawrence Little has shown, members of the African Methodist Episcopal (AME) Church carefully studied and debated the major international events of their day through the church’s main publications, the Christian Recorder and Church Review. An important national institution in the life of African Americans, the AME Church drew its leadership from the middle and professional classes of black America. In this respect the emergence of an elite group of African Americans interested in foreign policy closely paralleled the rise of a “foreign policy public” among white Americans.5 Other black-owned publications, including the Washington, D.C., Colored American, which was subsidized by Booker T. Washington and edited by Republican loyalist Edward E. Cooper, the more independent-minded Colored American Magazine (Boston), the New York Age, published by militant reformer Thomas T. Fortune, as well as journals in Kansas City, Indianapolis, Baltimore, and Cleveland, regularly covered events abroad.6

Advocates of commercial expansion and boosters of business opportunity among the black business community and the growing network of black-owned newspapers frequently used the same language as their white counterparts to promote economic expansion. African Americans who burned with a zeal to spread the gospel also sounded like their missionary brethren in the white community. But although African Americans trumpeted many of the traditional themes Americans regularly invoked to expand the empire of liberty, they often added their own variations to the old standards. By virtue of their common ancestry, African American missionaries, according to the Church Review, were also best equipped to carry the word to their unenlightened brothers and sisters in Africa and the Caribbean. Some missionaries saw themselves as fulfilling the biblical prophecy in which the displaced children of Ethiopia (Africa) returned to redeem their homeland for Christ. Others saw themselves as a civilizing vanguard in a secularized form of Ethiopianism. Various editors insisted that African Americans were ideally suited to develop the wealth of Africa and the South Pacific. Black promoters assumed that race offered African American migrants greater protection against the harsh climate and disease of the tropics while the advantages of American civilization would enable these pioneers to develop the land to its fullest potential. African Americans who sought opportunity in an expanding American empire also hoped that by exercising the same entrepreneurial spirit that their white compatriots prized so highly, they might finally be recognized as full citizens of the republic.7

If some believed that their race made them especially equipped to conduct America’s civilizing mission in the tropics, others recognized that American color prejudice forced them to cast their gaze outward in the first place. For these African Americans, their own battle against race prejudice at home led them to sympathize with the nonwhite subjects of empire around the globe. Discerning a color scheme in the pattern of Western imperialism, these budding internationalists rejected the idea that empire held benefits for anyone of color. How, they asked, could one prevent the spread of American racism within an expanding American empire? In 1898 the Spanish-American War and the seizure of the Philippines by the United States forced African Americans to confront this very question.

By the end of that year, what began as a war to liberate Cuba from a decadent Spanish empire verged on becoming a war to acquire Spain’s former empire in the Caribbean and Pacific. Like most Americans, African Americans supported the war against Spain as a war of liberation. Black volunteers rallied to the colors and fought gallantly in Cuba and Puerto Rico. The virtual unanimity within the black community soon fractured, however, when it became clear that President William McKinley would claim the Philippine Islands as a prize of war. When war broke out between American soldiers and Philippine nationalists, Henry M. Turner, a prominent AME bishop, castigated any black soldier who contemplated fighting in a war to deny another man his freedom and announced that “having once been proud of the flag ... as a Negro we now regard it as a worthless rag.” 8

A vocal but disorganized anti-imperialist movement also sprang up among white Americans, but many of these white opponents of empire were motivated by a racism even more virulent than that espoused by the paternalistic McKinley. Southern and western Democrats warned of a “mongrelization” of the white race and a tidal wave of unfit immigrants sweeping over the nation if the United States acquired the Philippines with its millions of dark-skinned natives. Like the northern genteel reformers who launched the Anti-Imperialist League, the predominantly Republican African Americans faced the painful choice of disavowing the party of Abraham Lincoln and making common cause with segregationist but anti-imperialist southern Democrats. When McKinley ran for reelection in 1900 against Democratic nominee William Jennings Bryan, the black press lamented that African Americans faced “a cruel choice of dilemmas, the racist imperialist or the racist anti-imperialist.” Some African Americans chose the “racist anti-imperialist.” The AME’s publication Voice of Missions grudgingly supported Bryan. But of those black Americans who were still able to exercise the franchise, most voted for McKinley. Party loyalty and the fear that racism at home might actually worsen under a Democratic president led many to support the Ohio Republican. Fear of a loss of party patronage also held black Americans fast.9

The discomfort that most black Americans felt in supporting McKinley was evident in the justifications they gave for their position. As disturbing as the acquisition of overseas empire was, they argued, it might yet benefit the cause of freedom at home and abroad. In endorsing McKinley in October 1900, the AME’s Review gave two cheers for Western imperialism. “The fact remains,” declared the Review, “that the rape of Africa, Asia and the islands will open them up to Western progressiveness, invention, comfort, personal liberty, and the Christian religion.”10 Others, including Bishop Benjamin Tanner and Theophilus Steward, an AME leader serving as an army chaplain in the Philippines, voiced the hope that the forced inclusion of millions of nonwhite subjects within the American empire might ultimately unite Americans of color in the cause of equality.

Whether one saw the Philippines as “Indian country” opened for homesteaders or the Filipinos as a people waiting in darkness for the benefits of Christian civilization, the response was one in which the American part of the African American identity held sway. Even Bishop Tanner’s dream, that non white subjects within the new empire might struggle together for equality under the same flag, was in many respects a nationalist solution to the problem of American racism. But the fierce struggle in the Philippines also produced a more internationalist response to the problem of imperialism. As early as 1899, a columnist in the AME’s Review declared: “if we further consider that almost all other movements involving the existence and integrity of weaker governments are against the dark races in Africa and Asia, and add to that the domestic problems of the American Negro, we are faced with a startling world movement.” Ending on an optimistic note, the writer predicted that events would one day unite the “dark skinned races” of the world. In the same magazine a year later, and only months after his famous pronouncement that “The problem of the twentieth century is the problem of the color line,” W. E. B. Du Bois also referred to a future global alliance of nonwhite peoples.11 One can readily see in these predictions of nonwhite solidarity some of the earliest stirrings of an idea that would come to have such a strong hold on black and white Americans for the next four decades.

In one sense, this belief in a global alliance of the oppressed was a response to the era’s pervasive racial theories that justified the subjugation of nonwhite peoples. Distorting the evolutionary concepts of Charles Darwin, academics and pseudoscientists worked hand-in-hand to promote the idea of white supremacy. Identifying themselves as members of a superior Anglo-Saxon race, American imperialists became self-described lawgivers who increased freedom by extending American rule. Although racial theorists spoke in terms of a racial hierarchy, ordering and reordering the place of such supposed races as Poles and Italians, all agreed that a vast chasm separated the alleged lesser breeds from the dominant whites. American leaders frequently justified the acquisition of overseas territory by asserting that this new imperialism was really not new at all. Americans had traditionally kept nonwhite peoples in a position of subordination for their own good, the advocates of empire argued; now they were just extending that system to the Philippines, Puerto Rico, and Hawaii. American soldiers in the Philippines made the point more bluntly by dehumanizing their Filipino adversaries with the same racial epithets they used to belittle blacks and Native Americans at home.12

It stood to reason, therefore, that the nonwhite peoples of the world would link arms in what one author has called “a fellowship of humiliation.” 13 But there was more to the idea of nonwhite solidarity than this tart description would imply. The belief in the possibility of a global league of nonwhite peoples was a daring and idealistic vision in an era of intense nationalism. American history was replete with examples of different peoples maintaining strong ties to their native lands. The idea of a global alliance of nonwhite peoples was different, however, in that it required black Americans to do more than simply stress the African side of their identify in looking at the world. A sense of kinship linking the lands touched by the African diaspora was an important part of African American thinking about foreign affairs, but what might be called “black internationalism” was unusual in that it reached beyond the world’s Black Belt to embrace nonwhite peoples everywhere as allies in the cause of liberation.

Although the spread of U.S. imperialism to Cuba, Puerto Rico, and the Philippines did the most to crystallize the thinking of black commentators about their relationship to subject peoples elsewhere, events in China between the mid-1880s and 1900 contributed to their growing sense of identification with the world’s darker races. During the 1880s writers in the AME publications regularly expressed sympathy for the Chinese who were victimized by French and British gunboat diplomacy. In 1884 the Review opposed Republican candidate James G. Blaine for his support of Chinese exclusion legislation. Nevertheless, when Japan fought China in 1895, the views of some African Americans were barely indistinguishable from those of white citizens. The Review greeted Japan’s swift defeat of China in 1895 as a victory for the nation that had more readily accepted Christianity. In humbling China, Japan had opened that haughty nation to the gospel.14

When Chinese patriots attacked American and European missionaries during the Boxer Rebellion, however, th...