- 520 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Pickett's Charge--The Last Attack at Gettysburg

About this book

Sweeping away many of the myths that have long surrounded Pickett's Charge, Earl Hess offers the definitive history of the most famous military action of the Civil War. He transforms exhaustive research into a moving narrative account of the assault from both Union and Confederate perspectives, analyzing its planning, execution, aftermath, and legacy.

Information

CHAPTER 1

THE LAST ATTACK AT GETTYSBURG

Lt. Frank A. Haskell first became aware that Friday, July 3, had arrived when he felt someone pulling on his foot. It was four o’clock in the morning, nearly a half-hour before the sun would rise, and Haskell had managed to get four hours of sleep. If the sky had not been so cloudy, he could have looked up and seen the moon hovering above the sleeping army. The first sound Haskell detected in the dark was the popping of skirmish fire, off to the right front of the Second Corps line. After two days of terrific fighting at Gettysburg, the generals were still not satisfied. Another day of bloodshed was needed to decide a winner and perhaps to settle the fate of the nation.

The man tugging at Haskell’s boot was Brig. Gen. John Gibbon, commander of the Second Division of the Second Corps. The two had fallen asleep in the Bryan peach orchard atop Cemetery Ridge, just behind the division line. Haskell found a cup of hot coffee and hastily drank it while getting ready to mount his horse and ride with Gibbon to discover the progress of the skirmishing. The general and his staff officer rode slowly, for neither of them were fully awake. Haskell noticed that most of the division was still asleep on the ridge, even though the skirmishers were only a few hundred yards away. As he looked to the left front, over the battlefield of July 2, he saw wounded horses limping through the growing light of dawn. The “ravages of the conflict were still fearfully visible,” Haskell wrote a few months later, “the scattered arms and the ground thickly dotted with the dead.”

There was little to fear from the skirmishers; they were simply firing in place rather than pushing or giving way. The skirmish lines remained stable, and only a few men now and then felt the sting of a round. There was time for Gibbon and Haskell to loll about and observe their men waking up with the sun. Soon the normal sounds and sights of a camp coming to life could be detected. “Then ensued the hum of an army . . . chatting in low tones, and running about and jostling among each other, rolling and packing their blankets and tents,” wrote Haskell. “But one could not have told by the appearance of the men, that they were in battle yesterday, and were likely to be again to-day. They packed their knapsacks, boiled their coffee, and munched their hard bread, just as usual, . . . and their talk is far more concerning their present employment, —some joke or drollery,—than concerning what they saw or did yesterday.”1

These were veteran soldiers who knew that taking care of the inner man was the most important preparation for battle. As they readied for the day, the sun rose higher, but it was often obscured by dark clouds all morning. Old soldiers knew that it usually rained right after a major battle, and the fighting on July 1 and 2 had been among the heaviest of the war. But the moon set at 7:29 A.M., and the clouds continued to break apart. There would be no rain today.2

To the right front of Gibbon’s division a lone regiment was waking up from its bivouac along Emmitsburg Road. The men of the 8th Ohio had been on skirmish duty since the day before. Most of the regiment had slept along the ditch that bordered the west side of the pike while their regimental comrades manned the skirmish line, which was along a rail fence farther west. The skirmishers were only about sixty yards from the Confederate skirmish line, yet the bulk of the Ohio unit had no trouble waking up with the dawn, undisturbed by the racket taking place a short distance west of their ditch. Despite the heat of this early summer, the night of July 2 had been a bit chilly. The sun warmed everyone; it “sent its rays upon unprotected faces and into blinking eyes,” wrote Lt. Thomas F. Galwey. The bluecoated soldiers rose with humped shoulders and outstretched limbs, “followed by a curious peering forward to see what the enemy, beginning to stir too, might be about.”

Back to the rear, along Cemetery Ridge, Galwey could hear “an angry neighing” from the battery horses. They were tired of carrying the harness “that for more than two days they had constantly worn.” The men on the skirmish lines could hardly afford to protest their fate; they spent the first moments of this day quickly building small fires to heat coffee. Galwey looked about and saw “little whiffs of blue smoke” rising into the air from numerous campfires. The sporadic skirmishing that continued on various parts of the line could not prevent these “determined spirits” from restoring their strength and energy with a much-needed dose of caffeine.3

Much the same scene was enacted on the opposite side of the field, separated from the Yankees by less than a mile of disputed ground. Col. Edward Porter Alexander was among the first to wake up, despite having spent part of the night tending to the placement of his guns. Alexander commanded an artillery battalion in Lt. Gen. James Longstreet’s First Corps and had been given temporary charge of several other battalions in the vicious battle the day before. He had visited Longstreet’s bivouac at midnight to receive instructions for the morrow and learned that the attack would be renewed. He was to select an advantageous spot for the Washington Artillery, not an easy task in the darkness. Yet the moon shone brightly at that midnight hour, and Alexander surveyed the battlefield, believing he saw a place for the guns that were to reach him at dawn.

Alexander was satisfied and sought a place to sleep at 1:00 A.M. The Sherfy peach orchard was on some of the highest ground along Emmitsburg Road. It had been the scene of particularly hard fighting the evening before when Longstreet’s men crushed the Union Third Corps. Now it was a mess, filled with “deep dust & blood, & filth of all kinds,” recalled Alexander. The orchard was “trampled and wrecked.” He found two fence rails and carefully placed them under a tree, used his saddle as a pillow, and fell asleep surrounded by human corpses and dead horses. He awoke two hours later after a “good sound & needed sleep,” having slept no more than two hours the night before as well.

While Gibbon and Haskell still lay and dreamed in their own peach orchard, Alexander began to putter around in the predawn darkness. He had only a dim knowledge of the Union position, but he could see, as the sun began to peek over the horizon, what he thought was the spot where Maj. Gen. Richard H. Anderson’s division had attacked the evening before. He assumed this spot was high ground just in front of the Federal lines and that a Rebel line of battle would appear there once the sun was fully risen. Therefore he directed the Washington Artillery to string out in a line through the Sherfy peach orchard, aiming toward that spot. Only later, when the sun was rising, did he realize his mistake. The high ground was Cemetery Ridge, and it was still held by the Yankees. Alexander scrambled to move his guns, fearing that they would be fatally enfiladed by the Union artillery as soon as the enemy gunners woke up and realized what an advantage Alexander had handed them. “It scared me awfully,” he confessed, but Alexander managed to readjust the line before any harm was done.

The entire area around the orchard was “unfavorable ground for us,” he reasoned. It was an open bump in the wide valley that separated Cemetery Ridge from Seminary Ridge, and the Yankees could see everything that was happening on it. “I studied the ground carefully for every gun to get the best cover that the gentle slopes, here & there, would permit,” Alexander wrote, “but it was generally poor at the best & what there was was often gotten only by scattering commands to some extent.” The only thing that saved him was a marked reluctance on the part of the Federals to open fire. Alexander was relieved to see that as the sun rose higher, there were only a few scattered rounds from the Union cannon. One of them wounded some gunners in the Washington Artillery, but Alexander refused to be drawn into a duel. The army had brought limited supplies of artillery ammunition, so he only allowed one or two rounds to be fired in reply, letting the Federals fire the last shot. Thus he could “beguile them into a little artillery truce. It worked excellently, & though, occasionally, during the morning, when we exhibited a particularly tempting mark we would get a few shots we got along very nicely.” All of Alexander’s arrangements were heartily approved by the army’s artillery chief, Brig. Gen. William N. Pendleton, when he visited the Sherfy peach orchard later that morning.4

PLANS AND EXPECTATIONS

Longstreet, too, was up before dawn to push forward a favored scheme of his, mounting a flank movement around the Union left. Anchored on Little Round Top and Big Round Top, the Federal left was secure against frontal attack but might be vulnerable to a smartly executed march around the hills. Longstreet had been reluctant to attack the left even on July 2, strongly favoring a less costly tactical plan. His men had fought magnificently in the late evening hours of the second and had come very close to seizing Little Round Top. But the casualties were exhausting, and a partial success was not enough for an invading army in enemy territory with little logistical support from home. Longstreet admitted long after the war that he did not intend for the July 2 assault to be pushed so far. He meant that he regretted so many men were lost for no decisive gain. “The position proving so strong on the 2d, I was less inclined to attack on the 3d, in fact I had no idea of attacking.”

With this frame of mind, the corps leader did not even ride to Gen. Robert E. Lee’s headquarters on Chambersburg Pike to consult with him on the night of July 2. Instead he sent a report of his assault and received a message from Lee that the attack should be continued the next day. He simply gave Longstreet a broad directive to resume offensive operations as soon as possible. Longstreet wanted to take the offensive but not with a frontal assault. He had dispatched scouts into the countryside to find a way for his command to sidestep the Federal left, then turn and “push it down towards his centre.” This, he presumed, could be accomplished with minimal bloodshed if the turning movement was successful. With the first light of dawn, Longstreet rode out to see for himself if a way around the heights could be achieved. His scouts offered encouragement, and Longstreet began to plan how his divisions might execute the maneuver. Lee typically gave the responsibility for planning details of operations to his subordinates, so Longstreet felt there was nothing wrong with choosing a line of attack that he personally favored.

His plan came crashing to a halt when Lee rode up about 4:30 A.M., just after sunrise. He was surprised at Longstreet’s proposed line of advance and ordered him to cancel it. The army leader then outlined his own thoughts on the coming offensive. He wanted the entire First Corps to strike the south end of Cemetery Ridge in a frontal assault. Two of Longstreet’s divisions, Maj. Gen. John B. Hood’s (commanded by Brig. Gen. Evander M. Law) and Maj. Gen. Lafayette McLaws’s, were already in line holding the Confederate right. They had conducted the fierce attack the day before and had lost at least a third of their strength. Maj. Gen. George E. Pickett’s division, not yet engaged in the battle, was on the field but not yet in position. It would serve as a support to Law and McLaws. Lee wanted to better Longstreet’s chances of success by coordinating an attack on the extreme left, to be conducted by Lt. Gen. Richard S. Ewell’s Second Corps against the Federal right. He had anticipated an early start, hoping to see the assault begin at dawn, and was disappointed it had not yet begun. This apparently had been his thinking all along, even the night before. It represented a continuation of the general plan of attack on July 2.

Longstreet was stunned. He had assumed that the results of the previous day’s action provided ample proof that frontal assaults were too costly and unlikely to produce results. He spelled out his views in clear language, arguing that “the point had been fully tested the day before, by more men, when all were fresh; that the enemy was there looking for us.” If Law and McLaws were withdrawn to attack the center, the Union left would be uncovered, allowing the Federals to advance and curl around Lee’s right wing. No less than 30,000 men were needed, with the support of the rest of the army, to bring a chance of success to this assault on the center; Law and McLaws and Pickett combined could muster no more than 13,000.

Instead, Longstreet suggested the army conduct a major shift to the right. Ewell should disengage from his position on the left, march laterally behind Lee’s rear, and position himself so as to hold the Union left flank in place on the rocky hills. The rest of the army would move to his rear and curve around to threaten the enemy rear, march five or six miles toward Washington, D.C., and find a strong defensive position. Then the Rebels could wait for the Federals to attack, slaughter them, and have the strategic initiative in hand. Longstreet later admitted in his official report that this proposed maneuver “would have been a slow process, probably, but I think not very difficult.” It was a plan that would come to assume almost mythic proportions in the decades after Gettysburg as a glittering alternative to what actually happened on July 3. Untested and therefore open to unrealistic expectations of success, this maneuver to the right became the great “might have been” of Gettysburg for those who wanted Lee to avoid the slaughter that was to come.

Longstreet hoped to tempt Lee with its possibilities. “General, I have had scouts out all night,” he told the army commander, “and I find that you still have an excellent opportunity to move around to the right of Meade’s army and manoeuvre him into attacking us.” But Lee did not take the bait. He replied, with “some impatience,” that a direct assault on the center was the true course of action. Thrusting his fist toward Cemetery Ridge, he said, “The enemy is there, and I am going to strike him.”

Lee based his decision on a considered opinion. He had been impressed by the results of the attack on July 2, when Ewell had hit the extreme right and Longstreet the extreme left of Maj. Gen. George G. Meade’s line. While Longstreet viewed these limited achievements as proof that something different should be attempted, Lee saw them as one step along the correct line of approach. The results “induced the belief that, with proper concert of action,” in Lee’s words, a similar movement could be successful on July 3. He believed that there had been too little coordination of effort and that the attack on the third had to be more minutely planned and closely executed. The capture of the Sherfy peach orchard especially encouraged Lee. It occupied the highest ground close to the Yankee line within Confederate reach, and artillery placed there could more readily support an infantry assault than any artillery post had done on July 2. Alexander had already come to the private conclusion that this was a false hope, but Lee grasped at every indication he could find to support his planned offensive. He counted heavily on the artillery to provide the key factor needed to bring success to this venture — artillery plus a well-coordinated tactical plan. Lee foresaw the guns softening the Union position and then moving forward to provide close support for the infantry when it attacked. He also wanted plenty of supporting troops on both sides of the assaulting column to be ready to rush in and exploit any success achieved. True to his command style, Lee did not intend to arrange this himself. He wanted Longstreet to be his right-hand man, as Stonewall Jackson had done on so many battlefields. Jackson had died less than two months earlier as a result of wounds received at Chancellorsville, and Lee was hoping Longstreet would fill his shoes.

Unlike Stonewall, Longstreet balked at the prospect of offensive action against the Yankees. Two other factors intervened to upset Lee’s plan. First, the terrain on the southern part of the battlefield was dominated by Little Round Top and Big Round Top. They had almost fallen to Lee’s troops the day before and were now held by Meade’s Federals in strong force. They could not be easily taken, and to strike the southern end of Cemetery Ridge just north of Little Round Top would expose the attacking column to flanking artillery fire and a possible counterattack. Longstreet argued that Law and McLaws needed to remain in place, fronting this sector of the Union line to anchor the army’s right wing. Lee soon agreed and allowed them to remain. He apparently had not fully appreciated the terrain difficulties on this part of the field, partly because Longstreet chose not to report in person on the results of the fighting the night before.

The second factor that changed Lee’s thinking came from the far left. During the long conversation with Longstreet, which had started just after 4:30 A.M., the sound of artillery fire could be heard to the north. Maj. Gen. Edward Johnson’s division of Ewell’s corps had attacked and captured some ground on the army’s left the evening before, at Culp’s Hill, which it held in close proximity to the Federal Twelfth Corps. Now, at early light, the Federals opened an artillery barrage, and a sharp fight ensued, leading Ewell’s command to attack without coordinating its movements with Longstreet. Historian William Garrett Piston has suggested that Lee might have implemented his plan anyway by promptly ordering Longstreet to throw Pickett, Law, and McLaws into a frontal attack against the southern end of Cemetery Ridge. Although late, this assault might have come off in time to give Ewell support. But Pickett’s division was not yet up and in line, averting any possibility that Lee’s desire for a cooperative attack on both flanks might take place that day.

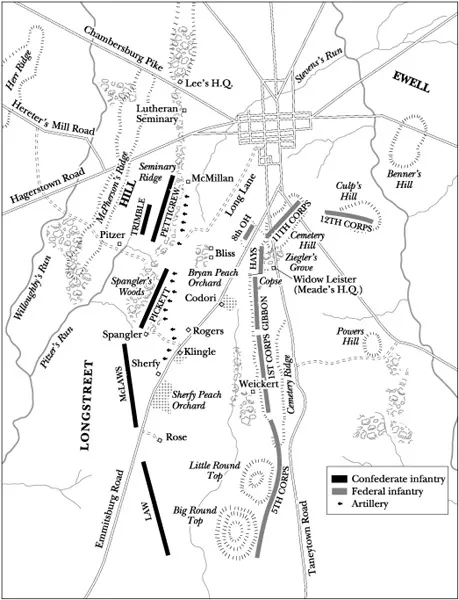

Map 1.1 Gettysburg, July 3, 1863

With his first plan now impossible, Lee devised his second plan for operations on July 3. Pickett would still be the key; his fresh division would spearhead an assault to take place much later in the day and hit the center of the Union position. Lt. Gen. A. P. Hill’s Third Corps, immediately to Longstreet’s left, would provide additional troops. When Longstreet asked how many men would be involved, Lee guessed 15,000. The corps commander was stunned. He had earlier suggested that twice this number was the minimum necessary. “General, I have been a soldier all my life,” he remonstrated, speaking more bluntly than ever before to Lee. “I have been with soldiers engaged in fights by couples, by squads, companies, regiments, divisions and armies, and should know as well as any one what soldiers can do. It is my opinion that no 15,000 men ever arrayed for battle can take that position.” He felt compelled to protest what he felt would be “the sacrifice of my men.” After this Lee lost all patience. Longstreet recalled that his chief was tired “of listening, and tired of talking, and nothing was left but to proceed.”5

Longstreet would brood over the results of this early morning conference for the rest of his life. He was firmly convinced that Lee’s plan would fail and cost the lives of irreplaceable men. It was to be one of the most complex and difficult attacks to organize during the entire war, involving elements of two corps, dozens of artillery units, and the thorny problem of coordinating supporting troops. The plan called for one of the most extensive artillery preparations ever to precede an infantry assault. Longstreet had never been given such a tough assignment.

Yet if anyone in the Army of Northern Virginia had the potential to organize it properly, it was Longstreet. Born in South Carolina forty-three years earlier, he had graduated from West Point in 1842. Longstreet was a consummate professional soldier, talented, self-confident, amiable, and almost destined to rise i...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Pickett’s Charge—The Last Attack at Gettysburg

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- CONTENTS

- MAPS

- ILLUSTRATIONS

- PREFACE

- CHAPTER 1 THE LAST ATTACK AT GETTYSBURG

- CHAPTER 2 THE ATTACKERS

- CHAPTER 3 THE DEFENDERS

- CHAPTER 4 THE BOMBARDMENT

- CHAPTER 5 TO EMMITSBURG ROAD

- CHAPTER 6 TO THE STONE FENCE

- CHAPTER 7 HIGH TIDE

- CHAPTER 8 THE REPULSE

- CHAPTER 9 GLORY ENOUGH

- EPILOGUE MAKING SENSE OF PICKETT’S CHARGE

- ORDER OF BATTLE

- NOTES

- BIBLIOGRAPHY

- INDEX

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Pickett's Charge--The Last Attack at Gettysburg by Earl J. Hess in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & American Civil War History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.