- 480 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

For much of the nineteenth century and all of the twentieth, the per capita rate of suicide in Cuba was the highest in Latin America and among the highest in the world — a condition made all the more extraordinary in light of Cuba’s historic ties to the Catholic church. In this richly illustrated social and cultural history of suicide in Cuba, Louis A. Pérez Jr. explores the way suicide passed from the unthinkable to the unremarkable in Cuban society.

In a study that spans the experiences of enslaved Africans and indentured Chinese in the colony, nationalists of the twentieth-century republic, and emigrants from Cuba to Florida following the 1959 revolution, Pérez finds that the act of suicide was loaded with meanings that changed over time. Analyzing the social context of suicide, he argues that in addition to confirming despair, suicide sometimes served as a way to consecrate patriotism, affirm personal agency, or protest injustice. The act was often seen by suicidal persons and their contemporaries as an entirely reasonable response to circumstances of affliction, whether economic, political, or social.

Bringing an important historical perspective to the study of suicide, Pérez offers a valuable new understanding of the strategies with which vast numbers of people made their way through life — if only to choose to end it. To Die in Cuba ultimately tells as much about Cubans' lives, culture, and society as it does about their self-inflicted deaths.

In a study that spans the experiences of enslaved Africans and indentured Chinese in the colony, nationalists of the twentieth-century republic, and emigrants from Cuba to Florida following the 1959 revolution, Pérez finds that the act of suicide was loaded with meanings that changed over time. Analyzing the social context of suicide, he argues that in addition to confirming despair, suicide sometimes served as a way to consecrate patriotism, affirm personal agency, or protest injustice. The act was often seen by suicidal persons and their contemporaries as an entirely reasonable response to circumstances of affliction, whether economic, political, or social.

Bringing an important historical perspective to the study of suicide, Pérez offers a valuable new understanding of the strategies with which vast numbers of people made their way through life — if only to choose to end it. To Die in Cuba ultimately tells as much about Cubans' lives, culture, and society as it does about their self-inflicted deaths.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access To Die in Cuba by Louis A. Pérez Jr. in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Latin American & Caribbean History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 Dying to Be Free

Suicide on the Plantation

The plantation is an archetypical world and materially structured by death.

He learned herbs, and medicines, and poisons, especially those. They killed animals in the fields with it, and of course they killed each other, and themselves sometimes. Macandal knew what we all do. Any death can hurt a whiteman somewhere. If it is only a slave or a cow, he is less rich.

In dying one gets the opportunity for a better life… . To die is to leave the visible world for the invisible; it is to say no to hunger, misery, disease, and worry.

There is no pity. His destiny is to suffer, always to suffer. And his only consolation is to turn his gaze upward to heaven and remind himself that one day he will die.

Cayetano was the family servant… . He was thin, with muscles of steel, a handsome face with symmetrical vertical scars on each cheek that revealed that he was Lucumí. He was of good intelligence, who knew how to read and write, with a valor that approaches heroism. He possessed a character different from those of his people, for he had not committed suicide, like so many of the Lucumí who had been brought to Cuba, for the simple reason that Frasquito had given him timely freedom so that he could come and go wherever he wanted.

Chinese labourers … have to endure hunger and chains, hardships and wrongs of every class, and are driven to suicide to the extent that no count can be made of the number of those who have thrown themselves into wells, cut their throats, [and] hanged themselves.

The specter of death loomed large over the plantations of nineteenth-century Cuba. It could not have been otherwise. Commercial agricultural production implied a vast capital outlay, from which profits were obtained principally through the relentless exploitation of human labor. Workers were readily expendable because they were easily replaceable, or perhaps it was the other way around. But it probably did not much matter, for property holders rarely gave more than fleeting thought to the rationale of human exploitation as long as labor needs were met.

The possibilities of prosperity seized the Cuban imagination late in the eighteenth century, in the aftermath of the collapse of plantation production in St. Domingue, revealing a potential for profits on a scale hitherto unimaginable. Cuban producers did not hesitate. Coffee cultivation expanded rapidly across the island, stimulated by increasing demand and rising prices. The number of cafetales (coffee plantations) increased from 2 in 1774, to 108 in 1802, to 586 in 1804; more than doubled to 1,315 by 1806; and almost doubled again to 2,067 by 1827. More than half of the total number of coffee plantations (1,207) were located in the Western Department (Occidente), principally in Pinar del Río, Havana, and Matanzas, and accounted for more than 75 percent of total Cuban production in 1827. Between 1792 and 1804, Cuban coffee exports increased more than sevenfold, from 7,101 arrobas to 50,000 arrobas (1 arroba equals 25 pounds), doubling thereafter every several years. Between the years 1825–30 and 1836–40 production increased annually from an average 2 million arrobas to 3.4 million arrobas.1

But it was sugar production that registered some of the most spectacular advances. The scope and speed with which land passed under sugar cultivation was stunning. Forests and woodlands disappeared almost overnight, to be reborn as vast expanses of sugarcane fields. The total amount of new land to pass under sugar cultivation nearly doubled from 510,000 acres in 1831 to almost 1 million acres in 1842, and increased again to nearly 1.5 million acres by 1852. The number of sugar mills (ingenios) increased threefold from 484 in 1778 to 1,442 by 1846. Exports increased in spectacular fashion, doubling from 28,400 tons in 1800 to 58,000 tons in 1809, nearly tripling to 162,000 tons by 1841. By midcentury, good times were buoyed by a record harvest of nearly 264,000 tons.2

Cuban prosperity was achieved through unimaginable human suffering, derived from the coerced labor of hundreds of thousands of enslaved Africans. They arrived in vast numbers, many tens of thousands of young men and women, in seemingly endless waves of human cargoes. During the intercensus years between 1792 and 1817 the population of enslaved Africans more than doubled from 85,000 to 199,000. But this was only the beginning. In the five-year period 1816–20 alone, an additional 85,000 slaves entered Cuba through Havana. Between 1830 and 1840, another 125,000 Africans arrived on the island. Between the two census years of 1817 and 1841, the total number of enslaved Africans had again more than doubled, from 199,0000 to 437,000.3 An estimated 184,000 of 437,000 slaves, that is, more than 40 percent of the enslaved population, had arrived on the island within the previous ten years. By midcentury, three-quarters of all slaves were located in the fields of rural Cuba, on coffee fincas and tobacco vegas, but mostly on the sugar ingenios. Fully one-half of the total number of enslaved people in rural Cuba were engaged in sugar production.

Africans consigned to sugar production toiled under execrable circumstances. Tens of thousands of men and women were worked remorselessly: six days a week, eighteen hours a day, often for five and six months at a time. Visiting one sugar estate in Güines during the expansion cycle of the 1830s, Richard Madden learned from a local overseer that the daily time allowed to slaves for sleep during the harvest “was about four hours, a little more or less. Those who worked at night in the boiling-house worked also the next day in the field… . The treatment of the slaves was inhuman, the sole object of the administrador being, to get the utmost amount of labor in a given time out of the great number of slaves that could be worked day and night.”4

This was a labor regimen from which there were few prospects of relief and even fewer possibilities of release, predicated on the proposition of optimum efficiency in pursuit of maximum profit. The practice of overwork—often literally working slaves to death—was not uncommon, almost always in the expectation that slaves thus lost could be replaced by others, on demand, at low cost and in limitless supply. “The idea of making the slave population supply itself is the last thing that seems to enter a Cuban’smind,” observed traveler Robert Baird. Alexander von Humboldt made the observation succinctly during his visit to Cuba: “I have heard discussed with the greatest coolness the question whether it was better for the proprietor not to overwork his slaves, and consequently have to replace them with less frequency, or whether he should get all he could out of them in a few years, and thus have to purchase newly imported Africans more frequently.” Joseph John Gurney observed a similar disposition among planters several decades later: “Natural increase is disregarded. The Cubans import the stronger animals, like bullocks, work them up, and then seek a fresh supply.” The death of slaves was passed off as depreciation of capital stock—all in all, an acceptable cost of doing business. “There are in Cuba plantations where the slaves work twenty-one out of the four-and-twenty hours,” Fredrika Bremer commented while visiting Cuba at midcentury, “plantations where there are only men who are driven like oxen to work, but with less mercy than oxen. The planter calculates that he is a gainer by so driving his slaves, that they may die within seven years, within which time he again supplies his plantation with fresh slaves, which are brought hither from Africa, and which he can purchase for two hundred dollars a head.”5

The logic of the plantation regimen did not readily admit the reproduction of the slave population through natural growth, demanding instead new purchases as the principal means through which to replenish the labor force (dotación). In the buyers’ market that prevailed during the early decades of the nineteenth century, the cost of reproduction exceeded the price of replacement. “[Planters] know that it is much cheaper to import slaves than to breed them,” Robert Baird observed tersely during his travels to Cuba.6 Former slave Juan Francisco Manzano gave poetic lament to these conditions:

What does it matter here, how many lives

Are lost in labour, while the planter thrives,

The Bozal market happily is nigh,

And there the planter finds a fresh supply:

’Tis cheaper far to buy new strength, we’retold,

Than spare the spent, or husband out the old;

’Tis not a plan by which a planter saves,

To purchase females, or to rear up slaves.

Are lost in labour, while the planter thrives,

The Bozal market happily is nigh,

And there the planter finds a fresh supply:

’Tis cheaper far to buy new strength, we’retold,

Than spare the spent, or husband out the old;

’Tis not a plan by which a planter saves,

To purchase females, or to rear up slaves.

…

But where, you ask me, are the poor old slaves?

Where should they be, of course, but in their graves!

We do not send them there before their time,

But let them die, when they are past their prime.

Men who are worked by night as well as day,

Some how or other, live not to be grey

Sink from exhaustion—sicken—droop and die,

And leave the Count another batch to buy.7

Where should they be, of course, but in their graves!

We do not send them there before their time,

But let them die, when they are past their prime.

Men who are worked by night as well as day,

Some how or other, live not to be grey

Sink from exhaustion—sicken—droop and die,

And leave the Count another batch to buy.7

“It is a rare thing to see a very old negro,” Mary Gardner Lowell confided to her travel journal in 1832.8

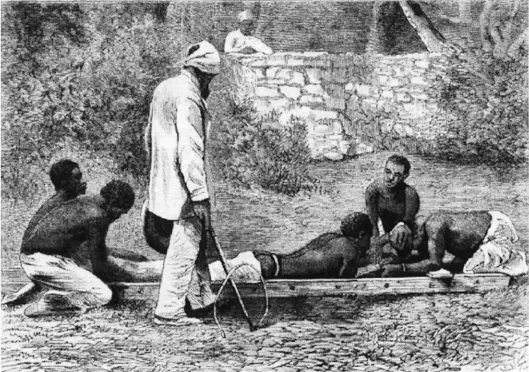

The discipline of the dotación was sustained through the application of corporal punishment and physical abuse, principally in the form of floggings, beatings, and mutilation. There was method to the means. Corporal punishment assumed fully the character of a system, with an internal logic of its own: cruelty applied purposefully with the intent of social control, to coerce compliance and enforce acquiescence, to give daily salience to the meaning of power and powerlessness by which the rhythm and rationale of the plantation system was sustained. Sanctioned cruelty and systematic violence as an acceptable and, indeed, within the logic of the colonial political economy, a necessary means of social control could not easily contemplate an alternative to the application of terror as a means to obtain both a disciplined labor force and an acquiescent mass of enslaved people. Punishment remained etched vividly in the memory of Juan Francisco Manzano:

For the slightest crime of boyhood, it was the custom to shut me up in a place for charcoal, for four-and-twenty hours at a time. I was timid in the extreme, and my prison … was so obscure, that at mid-day no object could be distinguished in it without a candle. Here after being flogged I was placed, with orders to the slaves, under threats of the greatest punishment, to abstain from giving me a drop of water. What I suffered from hunger and thirst, tormented with fear, in a place so dismal and distant from the house, and almost suffocated with the vapours arising from the common sink, that was close my dungeon, and constantly terrified by the rats that passed over me and about me, may be easily imagined. My head was filled with frightful fancies… . I would imagine I was surrounded by evil spirits, and I would roar aloud and pray for mercy; and then I would be taken out and almost flayed alive [and] again shut up.9

Punishing slaves. From Harper’sWeekly, November 28, 1869.

Punishment was also what runaway slave Esteban Montejo recalled vividly many years later. “I saw many horrors of punishment under slavery …,” Montejo remembered. “The stocks in the boiler-house were the most cruel. There were stocks for lying down and others for standing up. They were made of thick planks with holes through which slaves were forced to place their head, hands, and feet. They would keep slaves locked up like this for two or three months for the slightest offense… . The most common punishment was flogging. This was inflicted by the overseer with a rawhide lash which seared the skin. They also had whips made of the plant fibers which stung like the devil and peeled the skin off in strips… . Life was hard and bodies wore out.”10

Disease and illness claimed easy victims among the weak and weary. Smallpox, yellow fever, and tuberculosis were at once cause and effect of the appalling health conditions that prevailed among the dotaciones of hundreds of plantations. Deficient diets took their toll. Beriberi in particular became known as an illness associated with the sugar estates and often assumed epidemic proportions at the end of the harvest.11 Those fortunate enough to gain admittance to crude plantation infirmaries rarely obtained adequate medicine or competent care. In any case, illness was not sufficient reason to miss work. “When some black is seen to arrive at the infirmary without having a verifiable reason, as often happens,” counseled one plantation administrator, “faking illnesses with something like aches in his bones or somewhere in the body generally, lock him up in a room alone, subject him to an austere diet under lock and key … until hunger weakens him. Then without providing any food whatsoever and applying several lashes, return him to the overseer, so that he can be taken back to work. This way he will lose all interest in the infirmary.”12

Outbreaks of epidemics were common, and almost always resulted in devastating loss of life. Smallpox and typhoid fever periodically swept across the island. A cholera epidemic during the 1830s claimed the lives of thousands of enslaved men and women. Between March and April 1833, an estimated 2,100 slaves perished in Havana. In three jurisdictions of Madruga, Pipián, and Nueva Paz in Havana province, nearly 3,200 slaves perished between January and September 1833. In June 1833, an estimated 700 slaves on 18 sugar estates in the jurisdictions of San Andrés and Sabanillas in Matanzas province succumbed to cholera.13

Slave mortality rates reached staggering levels as the combination of ill-treatment and illness claimed the lives of many thousands of men and women. Death rates between 10 and 12 percent annually were not uncommon. On some ingenios annual mortality rates reached 15 to 18 percent. Mortality was especially high among newly arrived Africans, among whom Ramón de la Sagra calculated life expectancy on the sugar plantations to average less than seven years. This is also what traveler Robert Baird learned during his visit to Cuba during the late 1840s, when he recorded the conventional wisdom of the time: “It has been said, and it is generally credited by intelligent parties resident in Cuba, that the average duration of the life of a Cuban slave, after his arrival in the island, does not excee...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- To Die in Cuba

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Tables and Figures

- Illustrations

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- 1 Dying to Be Free

- 2 To Die for the Patria

- 3 Life through Suicide

- 4 A Way of Life, a Way of Death

- 5 An Ambience of Suicide

- 6 Patria o Muerte

- Epilogue

- Notes

- Index

- Series