eBook - ePub

Rethinking Aging

Growing Old and Living Well in an Overtreated Society

- 272 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Rethinking Aging

Growing Old and Living Well in an Overtreated Society

About this book

For those fortunate enough to reside in the developed world, death before reaching a ripe old age is a tragedy, not a fact of life. Although aging and dying are not diseases, older Americans are subject to the most egregious marketing in the name of “successful aging” and “long life,” as if both are commodities. In Rethinking Aging, Nortin M. Hadler examines health-care choices offered to aging Americans and argues that too often the choices serve to profit the provider rather than benefit the recipient, leading to the medicalization of everyday ailments and blatant overtreatment. Rethinking Aging forewarns and arms readers with evidence-based insights that facilitate health-promoting decision making.

Over the past decades, Hadler has established himself as a leading voice among those who approach the menu of health-care choices with informed skepticism. Only the rigorous demonstration of efficacy is adequate reassurance of a treatment’s value, he argues; if it cannot be shown that a particular treatment will benefit the patient, one should proceed with caution. In Rethinking Aging, Hadler offers a doctor’s perspective on the medical literature as well as his long clinical experience to help readers assess their health-care options and make informed medical choices in the last decades of life. The challenges of aging and dying, he eloquently assures us, can be faced with sophistication, confidence, and grace.

Over the past decades, Hadler has established himself as a leading voice among those who approach the menu of health-care choices with informed skepticism. Only the rigorous demonstration of efficacy is adequate reassurance of a treatment’s value, he argues; if it cannot be shown that a particular treatment will benefit the patient, one should proceed with caution. In Rethinking Aging, Hadler offers a doctor’s perspective on the medical literature as well as his long clinical experience to help readers assess their health-care options and make informed medical choices in the last decades of life. The challenges of aging and dying, he eloquently assures us, can be faced with sophistication, confidence, and grace.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Rethinking Aging by Nortin M. Hadler, M.D.,Nortin M. Hadler M.D. in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Medicine & Geriatrics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 ENLIGHTENED AGING

We all grapple with the greater meaning of death. Philosophers, theologians, and poets have been recruited to the task for eons. I have no special insights as to why we must die or what might follow, nor is my personal philosophy causing me to write this book. But we must die.

Aging, dying, and death are no longer solely the purview of philosophers and clerics. Many biological and epidemiological theories of aging have been articulated. Some are even testable theories, and many have been tested. The result is an informative science. We still have much to learn and many a theory that eludes testing, but the product of all this science is a body of information that has much to say to anyone today who wants to reflect on aging, dying, and death. This book is anchored on this body of information. Beyond reflection, aging, dying, and death have arrived at center stage in realpolitik at the urging of economists and for public-policy considerations given the needs of the burgeoning population of elderly.

Aging, dying, and death are not diseases. Yet they are targets for the most egregious marketing, disease mongering, medicalization, and overtreatment. This book is written to forewarn and arm the reader with evidence-based insights that promote informed medical and social decision making. All who have the good fortune to be healthy enough to confront the challenges of aging need such insights. Otherwise they are no match for the cacophony of broadcast media pronouncing the scare of the week or miracle of the month; pandering magazine articles; best-selling books pushing “angles” of self-interest; and the ubiquitous marketing of pharmaceuticals and alternative potions, poultices, and chants. All are hawking “successful aging” and “long life” as if both were commodities. We awaken every day to advice as to better ways to eat, think, move, and feel as we strive to live longer and better. We are bombarded with the notion of risks lurking in our bodies and in the environment that need to be reduced at all cost. Life, we are told, is a field that is ever more heavily mined with each passing year.

There are places on the globe where life is a literal minefield. There are others where it is a figurative minefield. The latter are places where a ripe old age is the fate of a lucky few, unconscionably only a few. Those places usually have as common denominators inadequate water and sewer facilities, unstable political structures, and dire poverty. They are a reproach to the collective conscience. However, I am writing this book for those of us fortunate enough to reside in the resource-advantaged world, countries that have crossed the epidemiological watershed so that it’s safe to drink the water. For us, death before our time is not a fact of life; it’s a tragedy. For us, a ripe old age is not a will-o’-the-wisp; it’s likely. And this happy and fortunate circumstance has almost nothing to do with what we eat, with our potions and pills, or with our metaphysical beliefs, and it has very little to do with the ministrations of the vaunted “health-care” systems that we underwrite. This will become disconcertingly, even painfully, clear in the chapters that follow.

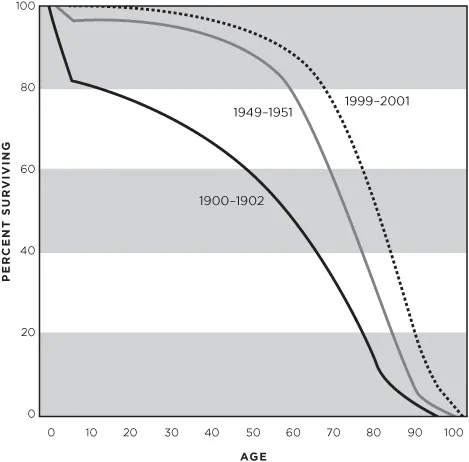

For now, we need to understand how fortunate we really are. Figure 1 displays U.S. longevity curves. The most recent curve that is available is based on census data that is a decade old. That bears witness to the challenges of finding out who is still alive and when, and at what age, the decedent died. Furthermore, the mathematical equations involved are very sensitive to small changes in age-specific death rates, particularly at the older age groups, when relatively few survive. The curves become more accurate in retrospect. Nonetheless, the message is obvious. Through the twentieth century, the likelihood of becoming an octogenarian increased greatly; the likelihood of becoming a nonagenarian barely budged, if at all. The idealized curve for our species is rectilinear; it is nearly flat because all would survive until their eighty-fifth birthday, more or less, when the curve dives as all die suddenly.

Figure 1 is more than the foundation for this book. It is a celebration of our time in the resource-advantaged world. Ours is not our grandparents’ longevity, not even our parents’ longevity. A “ripe old age” is no longer a literary device. We know how old one is when one is “ripe”: one is an octogenarian. To anchor our notions of aging and our notions of dying in any other timetable is irrational. Once I am an octogenarian, the issue is no longer longevity but the quality of the life of the aged. I don’t care how many diseases I have once I’m an octogenarian, or which of the many proves my reaper; I want to rejoice in the arriving at a ripe old age and know pleasure in the life of the aged.

Figure 1. Changes in U.S. longevity rates during the twentieth century. The survival curves over the twentieth century have become increasingly rectangular. This trend is obvious and dramatic prior to 1950. More and more, we are likely to become octogenarians, at which point the curves are increasingly vertical. (U.S. Public Health Service, National Vital Statistic Reports, vol. 57, no. 1, August 5, 2008)

Hence, “saving” or prolonging the life of an octogenarian is not a very useful goal. Those who live beyond their eighties can count themselves lucky, though seldom fortunate. Nonagenarians and centenarians, the “old-old,” are few and often forlorn. We know something of the biology of dying, enough to encourage venture capitalists to fund biotechnology enterprises seeking a molecular solution. Maybe, someday, there will be a molecular solution to the timing of a ripe old age. Don’t hold your breath. This book discounts that possibility.

In my most recent books, I addressed the health concerns of the working-age population. The Last Well Person: How to Stay Well Despite the Health-Care System (2004) focuses on medicalization and on Type II Medical Malpractice. Medicalization is reframing ordinary predicaments of life so that they are viewed as diseases. Type II Medical Malpractice is the doing of the unnecessary, even if it is done well. There are myriad examples of the untoward consequences of medicalization. As for Type II Medical Malpractice, it’s a scourge. My next book, Worried Sick: A Prescription for Health in an Overtreated America (2008), picks up both themes where the first book left off and points to the formulation of rational health-care reform. It was followed by Stabbed in the Back: Confronting Back Pain in an Overtreated Society (2009). In that work, I use the experience of low back pain to explore how the context in which backache is suffered, rather than the intensity of pain or its biology, determines the illness experience. Low back pain has spawned flawed health, disability, and compensation-indemnity schemes that are object lessons for health-care reform.

Rethinking Aging: Growing Old and Living Well in an Overtreated Society will take these ideas further, but my target here is not informing the general public about medicalization and Type II Medical Malpractice in order to influence the direction of health-care reform. Neither am I focusing on the population that is traditionally considered “working age.” Rather, I am addressing those who are approaching their later decades or have already entered them in order to arm them with the wisdom to question the advice they are receiving from all quarters and to help them conceptualize graceful and successful aging. Seldom will tradition, common sense, religious counsel, and personal fortitude prove a match for the medicalizing of everyday ailments. “Risk factors” abound, and we are told that every risk factor must be addressed—regardless of the benefit of treatment or lack thereof. We are told that every untoward personal challenge needs a biomedical explanation and a biomedical solution, or perhaps an alternative therapy. This book will arm you with the need and the ability to ask, “Does any of this really matter to me?” I want you to be able to make informed medical decisions. I want you to live out the last decades of your allotted fourscore and five as successfully, satisfyingly, and comfortably as possible, unfettered by worrisome notions of health promotion and unnecessary or harmful forms of disease management.

These last decades encompass the last years of gainful employment, the challenge of fulfillment in retirement, and the challenge of dying. It is apparent from Figure 1 that for prior generations of Americans, the interval between the end of gainful employment and the grave was brief. Today, it is not. In designing this book, I was tempted to divide it into three sections: the decade as an aged worker (fifty-five to sixty-five), the decade of unfettered active life (sixty-six to seventy-five), and the last decade. However, the sequence is far from inviolate and the timing highly variable. So the chapter that addresses the challenges of being an aged worker pertains whether you’re sixty or eighty, and so on. Furthermore, the chapters are not meant to represent passages, a procession from stage to stage. It is possible to be frail but not decrepit or frail and yet an aged worker. The chapters do not denote stations in life. They are important aspects of life that need to be understood, even savored.

Reading with a Prepared Mind

Rethinking Aging is neither a textbook of geriatric medicine nor yet another screed of the “Secrets to Good Health” genre. It is an exercise in logical positivism. In many of the chapters that follow, I employ object lessons to teach how one might make informed medical decisions in the various contexts that are relevant as one negotiates the challenges to health after sixty. Many of these object lessons are powerful because they illustrate errors in reasoning, mistaken beliefs, or misinformation. In some, the errors in reasoning are promulgated by purveyors who serve agendas other than the welfare of the patient. As a result, there is a sheen to Rethinking Aging that might be misinterpreted as “doctor bashing.” That is neither my intent nor my proclivity. We are all advantaged by the fact that the vast majority of physicians are bright, well trained, and well intended. I know this to be so because I have been privileged for nearly half a century to work among these physicians as colleague, mentor, and consultant. However, the American physician in particular is faced with enormous constraints that compromise ethical behavior—perverse constraints on their time wielded by reimbursement schemes. We can hope that a new institution of medicine will soon supersede one that is ethically bankrupt. Until then, it is crucial that all people who need to be or become patients have a prepared mind. Patients must maintain control of the diagnostic and therapeutic processes. In order to do so, they must be capable of asking about the potential benefits and risks, be willing to demand a detailed answer, and be prepared to actively listen to the answer. It is to this end that I’ve written Rethinking Aging, and it is to this end that I offer these object lessons.

Even Methuselah Died

Many may want to dismiss my discussion above. After all, Aunt Fannie or Uncle Bill lived to ninety-six, and Uncle Bill smoked and loved his doughnuts. Some want to argue that it’s all a matter of genes. This book will disabuse you of any such notion. Many genetic traits can conspire to cut short our lives: familial breast or colon cancers, exceptionally high cholesterol, and others. But longevity is not heritable. The reason Aunt Fannie and Uncle Bill made it beyond a ripe old age is stochastic; that is, they are lucky statistical outliers. You have no better chance of being a nonagenarian than if Aunt Fannie or Uncle Bill were not in your family.

Many will regard this as counterintuitive. After all, so many of the patriarchs of the Old Testament were really old. The Judeo-Christian-Islamic tradition holds these old men up as tantamount to gold standards. Longevity is treated as a sign of purposefulness, if not holiness. The Old Testament offers up Abraham, Moses, and that statistical outlier for the ages, Methuselah, the grandfather of Noah, whose age at death is usually translated as 969 years. Some scholars choose a different Sumerian dialect for translation or convert to lunar years and come up with an age closer to eighty-five—exceptional, not too shabby for the time of the Great Flood, and not fatuous, as is 969. We, the residents of the modern resource-advantaged world, are likely to live as long as Methuselah really did. The question I think we need to ask, however, is not simply how can we gain assurance that we will live eighty-five years but can we aspire to be purposeful and self-assured for eighty-five years?

Foreknowledge of the time of one’s death would be a heavy burden, not a blessing. Furthermore, if a world without death becomes a world without birth, the specter is bleak and joyless. Rather, for the Judeo-Christian-Islamic tradition and many polytheistic traditions, death is inevitable, and the imponderability of its imperative is assuaged with notions of an afterlife.

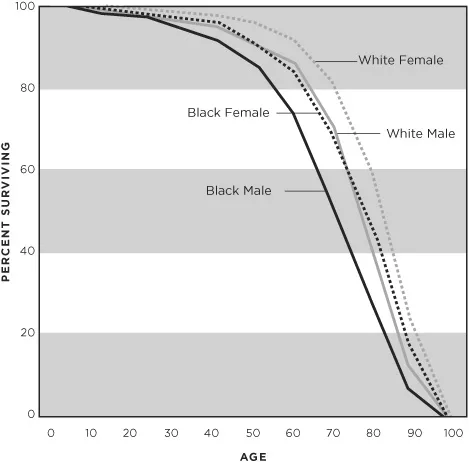

The idealized human survival curve has no infant mortality: we all live to eighty-five only to die on our eighty-fifth birthday. Figure 1 is impressive for the fact that survival curves in the United States in the twentieth century are trending toward this ideal. But the curve has a ways to go, and the curve for the United States has further to go toward the rectilinear ideal than that for nearly every other of our peers in the developed world. True, in America obesity, tobacco, high cholesterol, a health-adverse diet, inactivity, and so forth are contributing factors. And there is the suggestion that the particular makeup of our society is to blame. Figure 2 shows the racial and gender discrepancies in the most recent American survival curves. It’s easy to jump to the conclusion that being a black man in America automatically subtracts five years from one’s life expectancy. We have been pummeled with these inferences for so long and so intensively that they are part of the accepted wisdom. They are not entirely wrong, but nearly so.

Figure 2. Gender and racial disparities in U.S. longevity rates. The analysis of the 1999–2001 data illustrated in Figure 1 discerns impressive gender and racial disparities, illustrated here. (U.S. Public Health Service, National Vital Statistic Reports, vol. 57, no. 1, August 5, 2008)

In fact, the list of health-adverse behaviors and cardiovascular risk factors accounts for about 20 to 25 percent of one’s mortal hazard—that is, the years one falls short of a ripe old age. Furthermore, the mortal hazard inherent in these risk factors is not linear; you have to push the limits to pay this price. Just a little above whatever the “expert” consensus is for normal health behavior du jour imparts little if any hazard.

The remainder of a person’s mortal hazard, the bulk of it, relates to the circumstance of community. Beware if you are uncomfortable in your socioeconomic status; faced with a job you hate and have no options; poor; stigmatized in the pecking order; faced with uncertainties as to your future; or ostracized, alone, or lonely. These are some of the attributes of one’s ecosystem that chip away at longevity. With the exception of infant mortality, it makes no difference what continent one’s ancestors hail from.

All of this is in place before sixty-five, and after sixty-five it all plays out. Much of this was known to the sages of old, even to the authors of the Old Testament:

The days of our years among them are seventy years and if, with special attributes of strength and power, eighty years. (Psalm 90, usually attributed to Moses)

2 THE GOLDEN YEARS

This chapter and several that follow have an existential gloss: love, life, and death. But it is only a gloss. Generations of authors have offered up their philosophies, observations, preconceptions, prejudices, and metaphysical beliefs under a rubric such as successful aging, aging well, and the like. Some of this literature is sophomoric, some is quackery, much is self-serving, and much is simply fatuous. I have no inclination to review or even highlight that which I place in these categories. However, some is elegant, eloquently broadening the reader’s own personal philosophy. And some is scientific, applying the results of systematic studies to cause one to rethink preconceived notions. I am sorely tempted to try my hand at the eloquently broadening genre; hopefully, a little of such will insinuate into these chapters. But my strength as an author and educator is in this last category.

Our concern in this chapter is the health of those over sixty who are well. We know they are well because they tell us they are well. We know they are well because they tell us they are well despite, or regardless of, or even because of, the biologic imperatives of being over sixty.

All have a burden of disease. “Disease” is a term I use to designate anatomical and biochemical alterations from what would be considered “normal” in midlife. In my terminology, the symptoms that can be ascribed to “disease” by a physician are the “illness.” Some diseases are unusual at any age, like leukemia. But there are some that would be abnormal in youth but are so common after sixty that to be spared them is abnormal. Hence, there is a burden of disease that we all earn with each passing year. This is one of the messages of the next chapter, where we will discuss the nonspecificity of so many findings on screening tests. By sixty, some “diseases” are so normal that we dare not call them diseases, like graying or thinning hair—or do we? Illnesses are never normal, even if they are common. The ability to ascribe a particular illness to a definable disease is imperfect at all ages; this inability is commonplace in the elderly.

All have to cope with personal predicaments. We experience many unpleasant symptoms intermittently throughout life. No one escapes heartburn or heartache, headache or eye strain, back pain or knee pain, diarrhea or constipation, or more—at least no one escapes for long. Usually, we cope with such symptoms on our own. These I term predicaments. For some predicaments, we decide to turn to doctors, in which case the symptoms are our illness. The degree to which we can cope on our own is dependent on the context in which we experience the predicament. Aging is its own context.

All are learning to cope with the notion of their own mortality.

All are bombarded, day in and day out, by warnings and forewarnings related to their health. All listen to the scare of the week with one ear and the miracle o...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Rethinking AGING

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- CONTENTS

- PREFACE

- ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

- 1 ENLIGHTENED AGING

- 2 THE GOLDEN YEARS

- 3 STAYIN’ ALIVE

- 4 THE AGED WORKER

- 5 DECREPITUDE

- 6 FRAILTY

- 7 THE REAPER

- 8 AUTUMN

- NOTES

- ABOUT THE AUTHOR

- INDEX