eBook - ePub

Mary Breckinridge

The Frontier Nursing Service and Rural Health in Appalachia

- 360 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

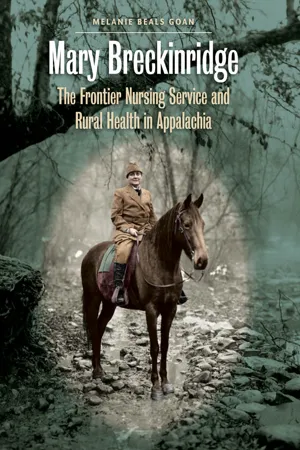

In 1925 Mary Breckinridge (1881–1965) founded the Frontier Nursing Service (FNS), a public health organization in eastern Kentucky providing nurses on horseback to reach families who otherwise would not receive health care. Through this public health organization, she introduced nurse-midwifery to the United States and created a highly successful, cost-effective model for rural health care delivery that has been replicated throughout the world.

In this first comprehensive biography of the FNS founder, Melanie Beals Goan provides a revealing look at the challenges Breckinridge faced as she sought reform and the contradictions she embodied. Goan explores Breckinridge’s perspective on gender roles, her charisma, her sense of obligation to live a life of service, her eccentricity, her religiosity, and her application of professionalized, science-based health care ideas. Highly intelligent and creative, Breckinridge also suffered from depression, was by modern standards racist, and fought progress as she aged — sometimes to the detriment of those she served.

Breckinridge optimistically believed that she could change the world by providing health care to women and children. She ultimately changed just one corner of the world, but her experience continues to provide powerful lessons about the possibilities and the limitations of reform.

In this first comprehensive biography of the FNS founder, Melanie Beals Goan provides a revealing look at the challenges Breckinridge faced as she sought reform and the contradictions she embodied. Goan explores Breckinridge’s perspective on gender roles, her charisma, her sense of obligation to live a life of service, her eccentricity, her religiosity, and her application of professionalized, science-based health care ideas. Highly intelligent and creative, Breckinridge also suffered from depression, was by modern standards racist, and fought progress as she aged — sometimes to the detriment of those she served.

Breckinridge optimistically believed that she could change the world by providing health care to women and children. She ultimately changed just one corner of the world, but her experience continues to provide powerful lessons about the possibilities and the limitations of reform.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Mary Breckinridge by Melanie Beals Goan in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Médecine & Biographies de médecine. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Choosing a Path

One Origins and Obligations

In the late nineteenth century, most Americans and certainly all southerners were familiar with the name Breckinridge. To be born a Breckinridge in the late nineteenth century brought with it a “birthright of advantages,” but it also carried a pressing sense of duty.1 Since arriving on the shores of the New World 150 years earlier, the family’s patriarchs had forged one of the nation’s most powerful political dynasties.2 Their dedicated, visionary contributions to the process of state building in Kentucky and to the development of the United States ensured the wide recognition of the Breckinridge surname. Male family members gained notoriety through politics as well as through their work as religious leaders, soldiers, educators, and newspaper editors. As an admiring supporter wrote in 1884, “The name of Breckinridge seems to fill the minds of the people.”3 Several years later, another ally remarked that the Breckinridge family represented an “aristocracy of courage and character, the only aristocracy possible in our country.”4

Possessing the Breckinridge name certainly opened doors, but this advantage came at a cost, placing tremendous pressure on young family members to perpetuate the tradition of service. Starting in infancy, Breckinridge children were “fed a steady diet” of their heritage to the extent that one claimed it “made life almost a burden.”5 Solemn portraits of renowned ancestors peered down on descendants as they scampered through the hallways of their homes. Letters and papers carefully preserved and shared provided instructions from beyond the grave as to how family members should behave.6 The idea was clear: a Breckinridge strove not simply to succeed but to excel.7

For female family members, to whom society offered limited options, the message that Breckinridges must prove themselves as outstanding members of society could be contradictory and frustrating. Born on February 17, 1881, Mary Carson Breckinridge was named for a long line of strong but submissive women.8 She grew up imbued with the message that Breckinridge males led while the women of the family, in their capacities as wives, sisters, and mothers, played nurturing and supportive roles behind the scenes. But at the turn of the twentieth century, when Mary came of age, options for women were beginning to expand. As a gifted, highly motivated member of the famous Breckinridge family who happened to be female, Mary felt driven to use her talents in a meaningful way and to capitalize on the opportunities being offered to the “New Woman.” The message that women belonged in the home, however, continued to weigh heavily on her. She would spend much of her life searching for creative ways to fulfill her obligation to advance the family name and to satisfy her driving ambition while still upholding her duty to remain within women’s appropriate sphere.

The migration that brought the first Breckinridges to Kentucky started nearly two centuries before Mary’s birth. Seeking religious freedom, the family moved from England to the Scottish highlands in the late nineteenth century and relocated soon thereafter to Ireland. Their displacement continued when the first Breckinridges sailed for the American colonies in 1728. They followed the path many Scots-Irish immigrants took, settling first in eastern Pennsylvania before moving down Virginia’s Shenandoah Valley. The first generations of American-born Breckinridges distinguished themselves as part of the frontier elite and quickly made their mark in local affairs. They accumulated great tracts of land in Augusta County, Virginia, and purchased slaves to work this land. Throughout the eighteenth century, Breckinridge males advanced through the ranks of the colonial gentry, holding influential positions such as sheriff and justice of the peace. An auspicious marriage to a member of the powerful Preston family further increased the value of the family’s stock. Although their future in Virginia appeared bright, some members of the family remained restless and began to look farther west.

The availability of cheap, high-quality land and the opportunities for political leadership within an infant state attracted John Breckinridge to Kentucky. Having sent his slaves ahead to clear land and build a comfortable home, he packed up his family and set out for the frontier in 1792.9 Kentucky in the late eighteenth century was an inviting though notoriously dangerous place. The Native Americans who used this region as a hunting spot and a travel corridor referred to it as a “dark and bloody ground.” Unfortunately for many settlers who tried to make it their home, this description proved accurate. Between 1783 and 1790 alone, an estimated fifteen hundred white individuals lost their lives in the Indian Wars. The hostile landscape and roaming white outlaws made the chance of death even greater. Still, many ambitious and optimistic individuals, lured by promises such as that made by one excited clergyman that heaven was “a mere Kentucky of a place,” were willing to overlook the risks. The region’s abundant resources proved too great a temptation to ignore.10

More fortunate than many, John Breckinridge’s gamble paid off. He and his family survived the dangers of the frontier, and his political connections and legal knowledge allowed him to establish himself quickly. Having served in the Virginia House of Delegates, Breckinridge became an active player in the developing Kentucky government. He helped revise the state constitution in 1799 and introduced the Kentucky Resolutions, which articulated an early version of the states’ rights philosophy. A loyal Jeffersonian Republican, he served as speaker of the Kentucky House of Representatives, as U.S. senator, and as U.S. attorney general before his death from tuberculosis cut short a promising career in 1806.11

John’s son, Joseph Cabell Breckinridge, appeared poised to spread the family’s political influence even farther, but he too died suddenly. Instead, his only son, John C. Breckinridge, was left to carry on the legacy. Family members trained the future statesman from infancy with this goal in mind. His grandmother, Polly, better known within the family as Grandma Black Cap, introduced young John C. to his grandfather’s ideals and philosophies. Thus, as he grew into adulthood, he displayed a clear sense of direction rare for a man his age. When combined with striking good looks and a gift for public speaking matched by few, this political grounding allowed him quickly to scale the ladder of local and state politics.12

Elected vice president of the United States on the Democratic ticket in 1856 at just thirty-six years of age, John C. Breckinridge took the national stage at a critical moment when the country struggled to solve the slavery crisis. He became the champion of states’ rights and the protection of slavery in 1860 when he ran unsuccessfully for president as the Southern Democratic candidate. Abraham Lincoln’s election triggered the secession of southern states. Though Breckinridge hailed from Kentucky, a state that at first declared neutrality and later chose to remain loyal to the Union, he pledged his support to the cause of Dixie. In the fall of 1861, the former vice president accepted a commission in the Confederate army as brigadier general. In so doing, he became the highest-ranking U.S. official to lead troops for the southern states, and he ultimately became Jefferson Davis’s secretary of war. The defeat of the Confederacy led to his exile, first to Cuba and subsequently to Europe and then Canada. Although he eventually returned to Kentucky, his political career had come to an end.13

The civil War irrevocably influenced the lives of the family’s future generations. More than any other factor, the legacy of the Civil War would shape Mary Breckinridge’s upbringing. Both of her parents, Clifton Rodes Breckinridge and Katherine Breckinridge Carson, came of age during the war, and they found themselves forever changed by their experience during these watershed years. Throughout his life, Clifton sought the success his father and great-grandfather had achieved, but he never attained the status expected of a man of his lineage.

When war broke out in 1861, Clifton Breckinridge, like many young men of his generation, welcomed the excitement and glory he expected the conflict would bring. Clifton was the second of six children born to John C. Breckinridge and Mary Cyrene Burch Breckinridge. Clifton was born in Lexington, Kentucky, in 1846 but spent much of his childhood at Cabell’s Dale, the family’s purebred horse farm located seven miles outside the city. Just fifteen when his father rode off to join the Confederate army, Clifton soon followed, enlisting as a private in a cavalry unit. He was eager to win glory on the battlefield but instead spent much of the war performing mundane tasks and running errands for his father.14

At the end of the war, nineteen-year-old Clifton stood on the brink of manhood, but he lacked a clear sense of direction. Now in exile, his father could not directly advise him, so family friends provided guidance and financial support. Following the Confederate surrender, Clifton worked for a time in a Cincinnati dry goods store before enrolling at Washington College in Lexington, Virginia. He was welcomed to campus in 1868 by hero and family friend Robert E. Lee, who had recently assumed the presidency of the institution, which was later renamed Washington and Lee College. Breckinridge was a diligent though mediocre student. He never earned a degree, but his time at “one of the most virulent rebel institutions in the land” further reinforced his identity as a southerner. Throughout his life, he took very seriously Lee’s advice to “stay with the South.”15

When he left school, Clifton was eager to establish himself, but the disfranchisement of former Confederates combined with the family’s reduced financial situation to leave him with limited options. In 1870, he moved to New Orleans and set himself up as a cotton merchant. He struggled for a time, serving as a middleman between planters and textile producers, before moving to Pine Bluff, Arkansas, to join his older brother as a cotton planter. This venture also proved unprofitable. He found the years 1870 to 1883 marked by economic uncertainty.

Despite his financial difficulties, Clifton won the hand of distant cousin, Katherine Breckinridge Carson. The couple married on November 21, 1876, in Memphis in what one historian has described as “an Old South wedding in a New South city.”16 The impressive heritage of both the bride and groom certainly was not lost on those in attendance. The son of former Confederate president Jefferson Davis served as best man, reminding guests that this ceremony was significant not only because it joined the lives of two individuals but also because it linked two prominent southern families. Guests undoubtedly found the occasion an opportunity to reminisce about the Confederacy’s past glories.17

Katherine Carson Breckinridge, like her husband, boasted an impressive pedigree. Born in 1853, she was the daughter of a wealthy Mississippi Delta cotton planter. Her father, James Green Carson, was the only son of an only son and consequently inherited a sizable estate comprising several thousand acres of prime land near Natchez, Mississippi, and nearly six hundred slaves to work it. Though the family later claimed that Carson morally opposed slavery and sought medical training to provide an alternative income that would allow him to free his chattel, evidence suggests that he manumitted only one bondsman during his life. Instead, Carson expanded his holdings in humans and land by purchasing Airlie Plantation on the Louisiana side of the Mississippi River in 1846.18

Katherine Carson grew up in the luxury so often romantically ascribed to the Old South. Visitors to her family’s estate traveled down a long tree-lined avenue, finally coming upon a mansion overlooking acres of well-manicured gardens.19 Reflecting their status within the community, Dr. Carson and his wife, Catherine Waller Carson, entertained “often and charmingly,” as one neighbor later recalled.20 Their close proximity to Natchez, a “bustling river town” with a “reputation for high living and notorious characters,” provided them ready access to the luxuries and conveniences of the day.21 On the eve of the Civil War, Natchez and its aristocratic nabobs boasted a higher concentration of wealth than any other town in the South.22

The war, however, took its toll. The Carson family’s fortune, like that of many white southerners, evaporated during the course of the conflict. Between 1860 and 1865, southern wealth declined by 43 percent, even excluding the value of slave property. During that period, cotton production fell to only one-tenth of its 1860 level. Fewer than 25 percent of antebellum plante...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Mary Breckinridge

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- Part One Choosing a Path

- Part Two The Frontier Nursing Service: The Building Years

- Part Three Establishing a Legacy

- Conclusion

- Epilogue The FNS after Breckinridge

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index