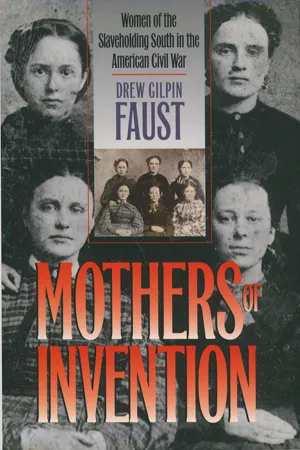

eBook - ePub

Mothers of Invention

Women of the Slaveholding South in the American Civil War

- 326 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

When Confederate men marched off to battle, southern women struggled with the new responsibilities of directing farms and plantations, providing for families, and supervising increasingly restive slaves. Drew Faust offers a compelling picture of the more than half-million women who belonged to the slaveholding families of the Confederacy during this period of acute crisis, when every part of these women's lives became vexed and uncertain.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Mothers of Invention by Drew Gilpin Faust in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & American Civil War History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER ONE

What Shall We Do?

WOMEN CONFRONT THE CRISIS

As the nation passed anxiously through the long and uncertain months of the “secession winter” of 1861-62, Lucy Wood wrote from her home in Charlottesville, Virginia, to her fiancé, Waddy Butler. His native South Carolina had seceded just before Christmas, declaring itself sovereign and independent, but Virginia had not yet acted. Just a week before Lucy Wood’s letter of January 21, her state’s legislature had voted to call a secession convention, and Wood thought disunion was “fast becoming the order of the day.” Yet these momentous events had already changed Lucy’s life. Waddy Butler, preoccupied with new military obligations in service of what Wood pointedly called “your country,” had been neglecting his intended bride, failing to write as frequently as she had come to expect. Affianced they still might be, but, Wood noted, they had become citizens of different nations, officially “foreigners to each other now.”1

In January 1861 Lucy Wood was more bemused than genuinely troubled by this intrusion of grave public matters into her personal affairs, and she fully expected Virginia’s prompt secession to reunite her with Butler in “common cause.” But beneath the playful language of her letter lay an incisive perception. Waddy Butler’s new life as a soldier would ultimately not just deprive his future wife of “hearing from you as often as I otherwise should,” but would divide the young couple as he marched off to war and she remained home in a world of women. By removing men to the battlefield, the war that followed secession threatened to make the men and women of the South foreigners to one another, separating them into quite different wartime lives. As the sense of crisis mounted through the early months of 1861 and as political conflict turned into full-scale war, southern ladies struggled to make the Confederacy a common cause with their men, to find a place for themselves in a culture increasingly preoccupied with the quintessentially male concerns of politics and of battle. Confederate women were determined that the South’s crisis must be “certainly ours as well as that of the men.”2

Public Affairs Absorb Our Interest

Like most southern women of her class, Lucy Wood was knowledgeable about political affairs, and her letter revealed that she had thought carefully about the implications of secession. Her objections to disunion, she explained to Waddy Buder, arose from her fears that an independent southern nation would reopen the African slave trade, a policy she found “extremely revolting.” Yet as she elaborated her position, detailing her disagreements with the man she intended to wed, Wood abruptly and revealingly interrupted the flow of her argument. “But I have no political opinion and have a peculiar dislike to all females who discuss such matters.”3

However compelling the unfolding drama in which they found themselves, southern ladies knew well that in nineteenth-century America, politics was regarded as the privilege and responsibility of men. As one South Carolina lady decisively remarked, “woman has not business with such matters.” Men voted; men spoke in public; ladies appropriately remained within the sphere of home and family. Yet the secession crisis would see these prescriptions honored in the breach as much as the observance. In this moment of national upheaval, the lure of politics seemed all but irresistible. “Politics engrosses my every thought,” Amanda Sims confided to her friend Harriet Palmer. “Public affairs absorb all our interest,” confirmed Catherine Edmondston of North Carolina. In Richmond, Lucy Bagby crowded into the ladies’ gallery to hear the Virginia Convention’s electrifying secession debates, and women began customarily to arrive an hour before the proceedings opened each morning in order to procure good seats. Aging South Carolina widow Keziah Brevard confessed that she was so caught up in the stirring events that when she awoke in the night, “My first thought is ‘my state is out of the union.’ “4

Like Lucy Wood, however, many women thought this preoccupation not entirely fitting, even if irresistible. Few were as adamant in their opposition to women’s growing political interest and assertiveness as Louisianian Sarah Morgan, who longed “for a place where I would never hear a woman talk politics” and baldly declared, “I hate to hear women on political subjects.” But most ladies were troubled by feeling so strongly about matters they could only defensively claim as their rightful concern. “I wonder sometimes,” wrote Ada Bacot, a young widow, “if people think it strange I should be so warm a secessionist, but,” she continued more confidently, “why should they, has not every woman a right to express her opinions upon such subjects, in private if not in public?” The “Ladies of Browards Neck” Florida demonstrated a similar mixture of engagement and self-doubt when they united to address the “politicians” of their state in a letter to the Jacksonville Standard. Their positive views on secession, they assured their readers, were not frivolous or ill-founded but were supported in fact and argument. “And if any person is desirous to know how we come by the information to which we allude, we tell them in advance, by reading the newspapers and public journals for the ten years past and when we read we do so with inquiring minds peculiar to our sex.” Rather than accepting their womanhood as prohibiting political activism or undermining the legitimacy of their political views, these Florida ladies insisted on the special advantages of their female identity, boldly and innovatively claiming politics as peculiarly appropriate to woman’s sphere.5

Catherine Edmondston worried about the vehemence of her secessionist views because of the divisions they were causing in her own family. Before Lincoln’s call for troops in April 1861, Edmondston’s parents and sister remained staunch Unionists, although Catherine and her husband of fifteen years strongly supported the new southern nation. Edmondston found the resulting conflict very “painful” and was particularly distressed at having to disagree with her father. “It is the first time in my life that my judgment & feelings did not yeild to him.” It was a “pity,” she observed, that politics had become so heated as to “intrude into private life.” Boundaries between what she had regarded as public and private domains were being undermined, as were previously unquestioned definitions of women’s place within them. As war consumed the South, Edmondston would find that little space was left to what she called “private life.” The private, the domestic, would become part of the homefront, another battlefield in what was by 1865 to become total war.6

In 1861, however, southern women still largely accepted the legitimacy of divisions between the private and the public, the domestic and the political, the sphere of women and the sphere of men. Yet they nevertheless resisted being excluded from the ever more heated and ever more engrossing political conflict that surrounded them. Women’s politics in the secession crisis was necessarily a politics of ambivalence. Often women, like men, were torn about their decision to support or oppose secession. Few white southerners of either sex left the Union without a pang of regret for the great American experiment, and just as few rejected the newly independent South without a parallel sense of loss. “It is like uprooting some of our holiest sentiments to feel that to love [the Union] longer is to be treacherous to ourselves and our country,” remarked Susan Cornwall of Georgia. As Catherine Edmondston explained, it seemed to her perfectly acceptable for a Confederate to “mourn over” the United States “as for a lost friend.”7

But women’s political ambivalence in the secession crisis arose from a deeper source as well: their uncertainty about their relationship to politics altogether. Admitting that they as women had no place in the public sphere, they nevertheless asserted their claims within it. Yet they acted with considerable doubt, with reluctance and apology, longing to behave as ladies but declining to stand aside while history unfolded around them. War had not yet begun, but southern women had already inaugurated their effort to claim a place and an interest in the national crisis.

Your Country Calls

What one Alabama lady called the “unexpected proportions” of the Civil War would take most Americans North and South by surprise. Many southerners anticipated that the Union would not contest southern secession, and James Chesnut, former United States senator from South Carolina, confidently promised that he would drink all the blood spilled in the movement for independence. Yet as soon as their states seceded, southern men began to arm and drill, and expectations of military conflict at once thrilled and frightened the region’s women. Looking back on those early days, one Virginia lady remarked that war had at first seemed like “a pageant and a tournament,” but others wrote of “foreboding for the future” or of a “trembling fear” of what might be in store. Disunion troubled Julia Davidson for reasons entirely apart from divisions of politics. “I study about it sometimes,” she wrote her husband, John, “and get The blues so bad I do not know what to do. God grant That all things may yet be settled without bloodshed.” As an elderly widow living alone on a large plantation, Keziah Brevard feared not just military bloodshed but worried too about what she called the “enemies in our midst,” the vulnerability of the South to slave uprisings.8

White southern women felt far freer than their men to admit—and even no doubt to feel—fears that, however unmanly, were entirely justified by the perilous circumstances facing the South. Women voiced apprehensions about war and anxieties about loss of particular loved ones, fears that masculine conventions of honor and courage would not permit men to express. From the outset this touch of realism tempered women’s politics and women’s patriotism; the culturally accepted legitimacy of women’s private feelings and everyday obligations posed a counterweight to the romantic masculine ideology of war. Soon after the passage of the Ordinance of Secession, a South Carolina lady offered her womanly resolution of the inconsistency between these imperatives, explicitly privileging the personal over the political, loyalty to family over obligation to the state. “I do not approve of this thing,” she declared. “What do I care for patriotism? My husband is my country. What is country to me if he be killed?” Kate Rowland of Georgia admitted that her “patriotism is at a very low ebb when Charlie comes in competition.” When her husband joined the army, she had no ambition for him to garner fame and glory; instead she wished him to secure a post as far as possible from all fighting. “Charlie is dearer to me than my country, & I cannot willingly give him up,” she confessed.9

The conflict between women’s emergent patriotism and their devotion to the lives and welfare of their families became clear as southern men prepared for war. Very precise expectations of men’s appropriate behavior in wartime enhanced many women’s enthusiasm for the Confederacy. The romance of the military and the close association of manhood with honor, courage, and glory outweighed the reluctance many women felt to give up their loved

Women watch the outbreak of war. “The House-Tops of Charleston during the Bombardment of Sumter.” Harper’s Weekly, May 4, 1861.

ones, for they had come to believe that the very value of these men was inseparable from their willingness to sacrifice their lives in battle. A “man did not deserve the name of man if he did not fight for his country,” Kate Cumming concluded. One lady of the Shenandoah Valley sent her son off to camp with a triumphant proclamation in the columns of the Winchester Virginian: “Your country calls. … I am ready to offer you up in defense of your country’s rights and honor; and I now offer you, a beardless boy of 17 summers,—not with grief, but thanking God that I have a son to offer.” Sarah Lawton of Georgia celebrated the opportunities she thought war would provide to make men more manly and to arrest what she regarded as men’s failure to fulfill her expectations of them. “I think something was needed to wake them from their effeminate habits and [I] welcome war for that.” Mary Vaught ceased speaking to those of her gentleman friends who had not enlisted, and a group of young women in Texas presented hoopskirts and bonnets to all the men in the neighborhood who did not volunteer.10

But the call for soldiers deeply troubled many women, who anticipated that their husbands and sons might well meet death rather than glory on the battlefield. Alabama widow Sarah Espy was distressed by her son’s determination to enlist. “I do not like it much,” she wrote, “but will have to submit.” Lizzie Ozburn of Georgia endured just a few weeks of army service by her husband, Jimmie, before herself arranging for a substitute to complete his term of enlistment. “Then if you don’t come,” she warned him, “you wont have any lady to come to when you do come.”11

The conflicting imperatives of patriotism and protectiveness played themselves out dramatically in the ritualized moment of troop departures. Communities gathered en masse to wish the soldiers farewell and often to present them with uniforms or flags sewn by local ladies. Patriotic addresses were the order of the day, and the soldiers marched off, as one young member of the elite Washington Artillery described it, “pelted with fruit, flowers, cards & notes” from throngs of ladies. Ceremonies of colorful uniforms, waving banners, patriotic speeches, and martial music displayed all the romance of war as well as unbounded expectations of personal courage and glorious victory.12

The ebullience of the crowd, however, often came at the expense of considerable repression of feeling. Gertrude Thomas spoke of the “speechless agony” with which she bade her husband good-bye, and Emily Harris seemed almost resentful that “It has always been my lot to be obliged to shut up my griefs in my own breast.” When one woman burst into tears before two young soldiers, their mother chastised her, “How could you, let them see you crying? It will unman them.” Men could evidently be men only with considerable female assistance.13

But often enough, women, especially younger ones, did break down. Sixteen-year-old Louisiana Burge described the reactions of her boarding school friends to the departure of a regiment from their Georgia town. Almost all the girls were weeping. “Em Bellamy spent nearly the whole evening in my room crying about the war and John T. Burr who leaves tonight. … Between her and cousin Emma Ward crying about Ed Gwinn I have had a time of it. … Ginnie Gothey’s feelings have overcome her; she has gone to bed, sick with crying about Bush Lumsden who don’t care a snap for he...

Table of contents

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Epigraph

- Dedication

- Table of Contents

- Illustrations

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction. All the Relations of Life

- Chapter One - What Shall We Do?: Women Confront the Crisis

- Chapter Two - A World of Femininity: Changed Households and Changing Lives

- Chapter Three - Enemies in Our Households: Confederate Women and Slavery

- Chapter Four - We Must Go to Work, Too

- Chapter Five - We Little Knew: Husbands and Wives

- Chapter Six - To Be an Old Maid: Single Women, Courtship, and Desire

- Chapter Seven - An Imaginary Life: Reading and Writing

- Chapter Eight - Though Thou Slay Us: Women and Religion

- Chapter Nine - To Relieve My Bottled Wrath: Confederate Women and Yankee Men

- Chapter Ten - If I Were Once Released: The Garb of Gender

- Chapter Eleven - Sick and Tired of This Horrid War: Patriotism, Sacrifice, and Self-interest

- Epilogue. We Shall Never ... Be the Same

- Afterword. The Burden of Southern History Reconsidered

- Notes

- Bibliographic Note