eBook - ePub

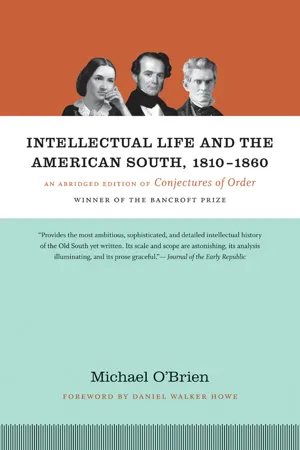

Intellectual Life and the American South, 1810-1860

An Abridged Edition of Conjectures of Order

- 400 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Intellectual Life and the American South, 1810-1860

An Abridged Edition of Conjectures of Order

About this book

Michael O'Brien has masterfully abridged his award-winning two-volume intellectual history of the Old South, Conjectures of Order, depicting a culture that was simultaneously national, postcolonial, and imperial, influenced by European intellectual traditions, yet also deeply implicated in the making of the American mind.

Here O'Brien succinctly and fluidly surveys the lives and works of many significant Southern intellectuals, including John C. Calhoun, Louisa McCord, James Henley Thornwell, and George Fitzhugh. Looking over the period, O'Brien identifies a movement from Enlightenment ideas of order to a Romanticism concerned with the ambivalences of personal and social identity, and finally, by the 1850s, to an early realist sensibility. He offers a new understanding of the South by describing a place neither monolithic nor out of touch, but conflicted, mobile, and ambitious to integrate modern intellectual developments into its tense and idiosyncratic social experience.

Here O'Brien succinctly and fluidly surveys the lives and works of many significant Southern intellectuals, including John C. Calhoun, Louisa McCord, James Henley Thornwell, and George Fitzhugh. Looking over the period, O'Brien identifies a movement from Enlightenment ideas of order to a Romanticism concerned with the ambivalences of personal and social identity, and finally, by the 1850s, to an early realist sensibility. He offers a new understanding of the South by describing a place neither monolithic nor out of touch, but conflicted, mobile, and ambitious to integrate modern intellectual developments into its tense and idiosyncratic social experience.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Intellectual Life and the American South, 1810-1860 by Michael O'Brien in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & History Reference. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1. The Softened Echo of the World

There are many ways to understand the interchanges between the South and the northern United States, but four are instructive for an intellectual history: the Southern experience of Northern higher education, the responses of Southerners traveling as visitors beyond the Potomac, the character of Northern judgments about the adequacy of Southern culture, and the debate within the South about the comparative standing of its culture.

In education, there was an asymmetry. The student bodies of Southern colleges were far less cosmopolitan than their faculty. Of the students who attended the University of Virginia between 1826 and 1874, for example, just 1.7 percent came from nonslaveholding states, and this was a mirror image of the Northern situation. With the exception of Princeton, few Northern colleges were hospitable to hiring Southern teachers. However, on average, between 1820 and 1860, Southerners represented about 9 percent of Harvard students, 11 percent of Yale’s, and 36 percent of Princeton’s.

Those Southerners who graduated in the North before 1815 seem to have experienced little cultural tension, and difficulties during the next two decades turned mostly not on political, but on pedagogical issues. Earlier Southerners knew they were moving among strangers, whose odd ways needed definition, but not always strangers who threatened survival. With the onset of abolitionism, the mood changed. In 1847 William Elliott observed that, during his recent visits to the North, he had stayed away from his own college of Harvard, because he was aware of “a difference in the tone” which had grown “out of political and sectional estrangement.” To his regret, his standing as a slaveholder now caused offense and seemed to place him in a position of “moral inferiority.” What happened in the 1840s to a postgraduate like Elliott happened then to undergraduate Basil Manly Jr., who went to study at the Newton Theological Institution in Massachusetts. After talking to a faculty member about the refusal of Northern Baptists to permit slaveholders to serve on foreign missions, he had grown troubled to be enjoying the “conveniences, advantages, & privileges” of an institution sustained by “men who cast out as evil my name, & the names of all I love & hold dear,” and decided to migrate to Princeton, where Southerners were more welcome.1

The impulse toward a growing separation was not only ideological but also institutional. The South in 1850 was richer in institutions of higher learning than in 1790, when effectively it had but one, the College of William and Mary. It was a pattern that fathers, born in the eighteenth century, went to English or to Northern colleges, but their sons to Southern. As the traveler John Melish observed even in 1815, “It was customary for a long period, for the more wealthy planters to send their sons to Europe for education; and even now they frequently send them to the northern states; but the practice is gradually declining, and the desire has become general to have respectable seminaries in the state.”2

Many Southerners went north not for education but pleasure. They considered the fashionable walkers along Philadelphia’s Chestnut Street and stayed at the Astor House in New York, from which they stepped out to be impressed (or not) by Broadway. There were bookshops, museums, and all the curious phenomena of modern life to visit: the new factories at Lowell, the great Fairmount Water Works in Philadelphia, the Shakers in New Lebanon. They went to churches, considered architecture, and judged preachers. They experienced landscape—Niagara, the Catskills, the Hudson River—and usually managed the required emotions of admiration or wonder. Above all, necessarily, they formed opinions on hotels, waiters, and menus.

Much was summed up by the word “manners,” by which was meant both customs and courtesies. It was expected that the traveler would observe manners, perhaps even learn from them, and they were variously judged, often in reaction to settled stereotypes. In general, it was presumed that Northerners were avaricious, brusque, rapid, religious (and probably hypocritical), disciplined, diligent, self-improving, less courteous to women, less hospitable, uncharitable toward social inferiors, condescending toward outsiders, self-righteous, less adept at politics, and more prone to ideological enthusiasm. Those who found good words for the North did so by demonstrating the inaccuracy of such prejudices. Lucian Minor in 1833, for example, was willing to admit that he had met “some admirable female minds in New England,” scant abolitionism, honesty, rational hospitality, and “a quiet, Sabbath-keeping, morals-preserving, good-doing, and heaven-serving religion.” All this was self-consciously intended to diminish hostilities, upon the presumption that Southerners too little visited the North: “Our people ought to travel northward more often. It would be a good thing, if exploring parties were frequently sent hither, (as to a moral terra incognita,) to observe and report the particulars deserving of our imitation.”3 But there is little evidence that there was a deficiency of such expeditions. Each year Southerners swarmed forth, and each year the ruts of mistrust deepened.

Implicated in such debates was the matter of mind. Were the intellectual exertions of the North more advanced? Later, the verdict of Appomattox seemed to settle the matter. Before 1861, the issue was murkier, at least for Southerners. Most Northerners, even Northerners not abolitionists, however, had little doubt of Southern inferiority.

At first, the North tended to see the South as pastoral and gentlemanly, a sort of English country estate, which might make people ignorant by forcing them into a “paradise of indolence.” In a Romantic age, this could be used by Northerners as a tool of self-criticism. In 1850, Emerson thought that the Southerner “has personality, has temperament, has manners, persuasion, address & terror,” but “the cold Yankee has wealth, numbers, intellect, material power of all sorts, but not fire or firmness.” Southern incompetence might occasion ambivalence, since it could be viewed either as a serious hindrance to national productivity or as merely a quaint nuisance. What sensible Northerner could feel challenged by what the Albany Evening Journal was later to assert of Southerners, that they were “dwarfs by the side of the giants of the North”? Did one need to fear what Henry David Thoreau called “a moral fungus”? Explanations for this inferiority differed. The rutted byways and dirty taverns might be blamed on slavery, but cultural etiolation might be understood as arising from a different descent; Northerners were energetic Anglo-Saxons, Southerners a mongrel people. Later, when it was clearer that an imperial South was less than supine, when the fungal dwarf bore the laurels of Mexico City on his brow, the images became darker. Then the North might be thought uncertain, the South purposeful. Theodore Parker put it starkly: “Southern Slavery is an institution which is in earnest. Northern Freedom is an institution that is not in earnest.”4 This was a class stereotype. If the South was aristocratic and the North democratic, the common man might be bewitched and herded by aristocrats who, if not intelligent, had ancestral habits of command and violence, even charm, and probably vice. The South came to embody what the North feared, that the great experiment of a moral, progressive republic might go awry. That is, the North saw the South as the continuation of Europe by other means; hence, to defeat her was to complete the project of the American Revolution. This was how Lincoln would come to explain matters over the dead of Gettysburg.

Francis L. Hawks of North Carolina, a historian and Episcopal minister in New York, felt the force of these condescensions in 1860. In his experience, Northerners “thought that the people of the South were a set of craven imbeciles” whose only purpose was to farm for the enrichment of Northerners, who in return “looked upon us as inferiors, morally, physically & intellectually.” A Southerner had only to look into the writings of Theodore Parker to find a sweeping indictment: “Whence come the men of superior education who occupy the pulpits, exercise the professions of law and medicine, or fill the chairs of the professors in the colleges of the Union? Almost all from the North, from the free States. . . . Whence come the distinguished authors of America? . . . All from the free States; north of Mason and Dixon’s line!” Traveling little in the South, never attending its colleges, seldom publishing in or reading its periodicals, why should Northerners be able to arrive at an estimate? Some were aware of this problem and even regretted it. In 1861 the historian Hugh Blair Grigsby sent some of his publications to Cornelius Felton of Harvard, who in reply praised the Virginian’s “eloquent and instructive pages” and mused on his ignorance of the Southern mind after the generation of Jefferson: “I could not help regretting that our country has not a common center where from time to time the men of letters, and leading professional gentlemen may meet, and become personally acquainted with each other. Your books have taught me how little I know of the literary works of Virginia, and how much there is in them which I and all our northern men ought to know.”5

So Southerners observed the North more than they were observed and were very unsure about their standing. There was a school of opinion that believed the South was too dependent upon the North, both economically and intellectually. In the 1820s, Robert Young Hayne sought expansively to remedy this thralldom by proposing a periodical that might educate and stimulate the Southern elite, which, in turn, would give “tone to the sentiments and opinions of the people.” Though they aimed at arousing and defining Southern intellectual energies as a counterpoise to Northern views, the founders of the Southern Review did not intend a closed world. Knowledge of “the improvements of the age” would be diffused in the South, intellect would arise from its slumber, write, and be read, but not only in the South. The place would come to define itself, but also would persuade others by a journal which might occasion “the diffusion of knowledge, the discussion of doctrines, and the investigation of truth,” and so extend “the boundaries of human knowledge” and review “the opinions of the days as in their perpetual fluctuations they set on the characters and conduct of society.”6

Intellectual life mattered because it molded public opinion, which controlled much of life. Knowledge was power, as Thomas Cooper passionately insisted in 1831, and it was worrying that in the “perpetual fluctuations” of modern society the South might lose ground. Any culture could fear that, even those which bestrode the world. Victorian Britain was riddled with doubt. So Basil Manly spoke of “the inferiority of our [educational] Institutions” and others looked at solid things like the North American Review in Boston and fretted when Southern periodicals tottered, as they regularly did.7

Not all the estimates, however, were self-abasing. Many considered the South as superior in the political arts and political thought. Conservative theologians thought little of Northerners who had strayed into liberalism, and, in general, Northern classical scholarship was deemed inferior. In the early 1830s, Edward W. Johnston, who had been librarian of South Carolina College, went north and found the experience discouraging. He had fallen into a respectable enough set, including William Cullen Bryant and James K. Paulding, but these, in comparison to the intellectuals of Columbia, seemed like lightweights. There was “nobody with Dr Cooper’s Atlantean shoulders, fit to prop a whole world of volumes; nor none with Nott’s nice fingers, that touch every thing, and know how to touch it so choicely and deftly; nor Lieber’s sturdy German grasp, that wields so much, by dint of taking every thing by its handle; nor Preston’s noble and elegant capacity that possesses itself, in a glance, of the better parts of all knowledge.”8 So, some were sure that the South was inferior, some that it was superior, some made distinctions within genres, others between institutions. Some were driven by a political vision; others were blithely indifferent to politics and cared only for God or verse forms.

In all this, it would be easy to exaggerate dissidence, even late in the antebellum years when tensions grew. Incomprehension was the norm, but a few set their boats against the current. Some relationships survived the strains, others even flourished. Nonetheless, amiability was impeded by the complexity of the American scene. To his friend Francis Lieber, then removed to New York, William Campbell Preston (the politician and college president) remarked in 1859 upon the evil of a “lack of a common center of thought” in the Union. “Washington is in no sense metropolitan, nor is New York except in respect to commerce,” he observed. “The thought . . . of that great amorphous ag[g]regation of people and effort is hardly perceived here in Virginia.”9

As the bitter history which created a civil war was to show, this fumbling ignorance could occasion hostility as often as indifference. Silence could be intimidating, when there was no center and no hope of any portion achieving intellectual dominance, but only fragments that postured, groped, and wondered.

THE SOUTH HAD ITS centrifugal forces, which touched its black population most powerfully: for Frederick Douglass, William Wells Brown, or Harriet Jacobs, this was a place to leave. But, for whites elsewhere, the South appeared prosperous, somewhere futures could be made. The presence of these “aliens” took many forms; visitors, settlers, sojourners—the temporary, the permanent, and the uncommitted.

Often noticed have been those who came briefly. These included friendly Northerners like James K. Paulding, ambivalent ones like Frederick Law Olmsted, hostile ones like Harriet Beecher Stowe. And then there were the foreign commentators, like Alexis de Tocqueville and Basil Hall. The early nineteenth century liked to travel, liked to write books about it, liked to have opinions about the alien. The South was on the circuit, though peripherally, being not so remote as to offer the shock of the new, nor so familiar as to provide the shock of recognition.

Foreign opinions rebounded back to the South, which took them with varying degrees of indignation, curiosity, and enthusiasm. Southerners, like other Americans, were notoriously sensitive about alien opinion. Table manners, the brutality of the roads, the brown slime of tobacco juice, the perils of democracy, such things were the standard topics of interest to foreigners perambulating in both Ohio and Alabama, and the standard occasion for local resentment. Slavery was an especial vexation. The institution, Southerners were persuaded, could only be understood by those who stayed more than a few months, certainly more than Mrs. Stowe’s few days in northern Kentucky. A character in Susan Petigru King’s novel Lily lays it down as a maxim that abolitionists should be obliged to stay for a year before they could earn their opinions.10

There was, especially, a steady supply of British writers who traveled through the South, though the trade routes were unhelpful. Invitations to American tours often came from Northern publishers, and the visitor’s first contacts seldom encouraged a Southern venture. From New York in 1842, Charles Dickens wrote of his plans to go to Charleston, but upon advice he changed his mind: “The country, all the way from here, is nothing but a dismal swamp . . . [and] there is very little to see, after all.” Slavery was a great barrier, especially for Dickens: “When we reach Baltimore, we are in the regions of slavery. . . . They whisper, here [in New York] . . . that in that place, and all through the South, there is a dull gloomy cloud on which the very word seems written.”11

But visits by foreigners could bring into Southern culture a fund of knowledge, allusion, and gossip. The geologist Charles Lyell, for example, came often enough to become a familiar figure among Southern scientists. Thackeray became especially close during and after two lecturing tours in 1853 and 1856, when he was handed on from literary luminary to wealthy notable, from Baltimore via Charleston to New Orleans. In Richmond in 1853 he was a particular hit, his discourse later inducing fond memories of a “charming manner and musical voice,” a geniality which altered previously critical opinion of the novelist’s cynicism.12 The fondness was reciprocal, enough to induce Thackeray to write The Virginians and not The Bostonians. The place was warm, the Médoc and bouillabaisse in New Orleans were excellent, there were agreeable and well-informed people. As a matter of principle, Thackeray leaned toward generosity, and, though a great admirer of Dickens, he had not approved of the American Notes, which he thought showed dis-courtesy and an ignorant temerity in hazarding a book on a culture which Dickens barely knew. Thackeray preferred to pocket his lecture fees, thank his audiences, and not add insult to benefit by dashing off a quick travel book. He was studiedly polite about what he saw, was only gently satirical, and tried to take no sides in American sectional disputes. But not to attack the South was, willy-nilly, to defend it. And, in truth, he saw little in slavery to trouble him. From Washington he wrote to his mother in 1852: “They are not my men & brethren, these strange people with retreating foreheads, with great obtruding lips & jaws: with capacities for thought, pleasure, endurance quite different to mine.” In theory, he denied the morality of slavery, but not in extenso. Moreover, Thackeray felt that Southerners had a point when they indicated the inhumanities of English society: “God help us we are no better than our brethren.”13

Then the South was full of migrants: some Northerners, some Europeans, some who came to stay, some who moved on. Among those who stayed, the case of Thomas Smyth, the theologian and Presbyterian minister, is instructive, because he tried to do what many migrants preferred, to effect a balance between his new place and his old one.

He started life as plain Thomas Smith, born in Belfast in 1808, and educated under the auspices of the Scottish Enlightenment. He came to America, partly to follow his emigrating parents, partly to escape disciplinary embarrassments at his college, partly to unburden himself of a failed romance. In the United States, he abruptly switched from Congregationalism to Presbyterianism, studied at Princeton, and was about to become a missionary in Florida, when he was invited to supply a pulpit in Charleston. There he found many Scotch-Irish who did not expect him to relinquish his former ties.

Smyth (as he became in 1837) turned into an assimilated Southerner and, what was extra, a proslavery Charlestonian, but he never abandoned his stake in North Britain, where he republished his works. As a theologian, he remained knitted into a transatlantic culture even while slavery complicated his relationship to it. In 1850, for example, he was nominated for an honorary degree at the University of Glasgow and the university’s senate declined, believing it was unwise to meddle in the slavery question. This was but one of several incidents that indicated a gulf. In 1843, when the Free Church of Scotland had been founded, Smyth had taken up a very large collection in Charleston and sent it to Thomas Chalmers in Edinburgh. Thinking a Christian slaveholder to be no oxymoron, Chalmers was pleased, but others were not, including Frederick Douglass. In lectures in Belfast, Douglass had forcefully urged that there was, indeed, a contradiction and that morality required Christians to reject the fellowship of slaveholders. In Scotland, Douglass then urged that subventions from slaveholders be returned. “Send ...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Intellectual Life and the American South, 1810–1860

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Foreword

- Preface

- Introduction. The Position and Course of the South

- 1. The Softened Echo of the World

- 2. All the Tribes, All the Productions of Nature

- 3. A Volley of Words

- 4. The Shape of a History

- 5. Pride and Power

- 6. Philosophy and Faith

- Epilogue. Cool Brains

- Notes

- Index