eBook - ePub

Imagining New England

Explorations of Regional Identity from the Pilgrims to the Mid-Twentieth Century

- 400 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Imagining New England

Explorations of Regional Identity from the Pilgrims to the Mid-Twentieth Century

About this book

Say “New England” and you likely conjure up an image in the mind of your listener: the snowy woods or stone wall of a Robert Frost poem, perhaps, or that quintessential icon of the region — the idyllic white village. Such images remind us that, as Joseph Conforti notes, a region is not just a territory on the ground. It is also a place in the imagination.

This ambitious work investigates New England as a cultural invention, tracing the region’s changing identity across more than three centuries. Incorporating insights from history, literature, art, material culture, and geography, it shows how succeeding generations of New Englanders created and broadcast a powerful collective identity for their region through narratives about its past. Whether these stories were told in the writings of Frost or Harriet Beecher Stowe, enacted in historical pageants or at colonial revival museums, or conveyed in the pages of a geography textbook or Yankee magazine, New Englanders used them to sustain their identity, revising them as needed to respond to the shifting regional landscape.

This ambitious work investigates New England as a cultural invention, tracing the region’s changing identity across more than three centuries. Incorporating insights from history, literature, art, material culture, and geography, it shows how succeeding generations of New Englanders created and broadcast a powerful collective identity for their region through narratives about its past. Whether these stories were told in the writings of Frost or Harriet Beecher Stowe, enacted in historical pageants or at colonial revival museums, or conveyed in the pages of a geography textbook or Yankee magazine, New Englanders used them to sustain their identity, revising them as needed to respond to the shifting regional landscape.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Imagining New England by Joseph A. Conforti in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & North American History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

The Founding Generation and the Creation of a New England

Puritan settlers decidedly shaped the intellectual and cultural history of early New England, but they did not coin the term. Instead, the Puritans wrested imaginative possession of “New England” from more secular promoters and visionaries, principally explorer Captain John Smith, who originated and popularized the name. Laboring to achieve rhetorical dominion over the region, the Puritans proceeded to give it a distinctive colonial birth.

The storied Puritan settlement of New England occurred in one concentrated burst of migration during the 1630s and early 1640s that propelled upward of 21,000 English colonists to the region. The Puritans, who dominated this migration, journeyed to the New World in “companies”—organized bands of kin, neighbors, friends, and fellow church members—that helped sustain both memories of their homeland and persistence in their “new” England.1 From the early 1640s to the end of the century and even beyond, New England received minimal in-migration. Yet its population surged, driven by a high birthrate and a low deathrate that testified to the region’s hearty environment.2 Thus, New England remained a relatively homogeneous English area from its origins to well into the nineteenth century. History poorly prepared it for the wrenching process of ethnic change that would transform the region beginning in the middle of the nineteenth century.

It was not so much cultural homogeneity, however, that marked New England as a distinctive New World colonial society but other characteristics of the Puritan migration. Middle-class families filled the ranks of the Puritan hegira to the region; neither the impoverished nor the wealthy migrated in significant numbers. New England began and developed as a middle-class society of wide property ownership, a sharp contrast to the social reality of other New World colonies. Most important for the fashioning of a conceptually and rhetorically dense regional identity, the founding settlers comprised an unusually literate, educated group, especially for a colonial population. The founders’ verbal prowess derived from their Puritan faith.3

Unlike the small band of Separatists who had settled Plymouth Plantation beginning a decade earlier, the Puritan founders of New England sought not to break away from the Church of England but to “purify” or reform it of entrenched Roman Catholic trappings. The erection of autonomous, nonseparating Congregational churches would preserve the restorationist impulse of the Protestant Reformation until the English homeland was ready to become a spiritual successor to biblical Israel. Puritanism was a religion of the word—of a devotional discipline rooted in literacy, Bible reading, and sermonizing, rather than ceremony, ritual, and such sensualism as churchly icons and instrumental music. From its founding Puritanism conferred on New England the highest rates of literacy in the New World. Puritanism was responsible for the first printing press in colonial America, established at Cambridge in 1640. Puritanism transported a cadre of well over a hundred college-educated intellectual leaders to New England. Graduates of Cambridge and Oxford, the intellectual elite among the founding generation consisted primarily of ministers but also included lawyers such as Governor John Winthrop. Through promotional tracts, sermons, correspondence, and, later, historical accounts, New England’s cultural representatives fashioned a collective image for the region. In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, they presented a literate population with a torrent of publications focusing on the purpose and history of New England’s creation, forging a print culture of regional consciousness unique in the annals of New World colonization.4

But creating New England, that is, imaginatively drawing the boundaries of regional identity, involved an ongoing process of cultural negotiation. For New Englanders were both English colonials and Puritan religionists, interwoven underpinnings of their identity that changed over time. As colonials and Puritans, New Englanders in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries negotiated their identity in response to a shifting relationship with England. They confronted what has been described as the central dilemma of a colonial identity. Colonial societies faced the predicament “of discovering themselves to be at once the same and yet not the same as the country of their origin,” a quandary that was complicated by the fact that mother countries held colonies such as New England in disesteem.5 New England identity from the founding to the eighteenth century may be approached as a rhetorical map that recorded and attempted to impose conceptual order on the changing circumstances of both the region’s colonial status and its Puritan religious culture.

The literate middle-class founders of the region conceived of it as a second England and transferred English place-names to the New World. “That it might not be forgotten whence they came,” an early Puritan historian observed, the settlers “imprint[ed] some remembrance of their former habitations in England upon their new dwellings in America.”6 The founding generation saw the region as a “new” England where they could re-create ancestral English culture, reform the national church, and generally restore an industrious, pastoral way of life that they associated with an idealized English past. The founders’ encounter with the New World served less as a catalyst for an emergent American identity than as a colonial setting for the reaffirmation of their English origins.

Whatever the problems of contemporary England that prompted the Puritans’ transatlantic flight, for the pious John Winthrop no less than for the worldly John Smith “New England” announced a quest for cultural continuity with the homeland. Smith, the erstwhile leader and pugnacious Indian fighter of the Virginia Colony, explored the New England coast in 1614 and coined the region’s name two years later. For Smith and the Puritan planters who later seized both physical and imaginative possession of the region, New England embodied a vision of the Northeastern coast of the American continent as a cultural and even environmental extension of England. Long before John Locke announced that “in the beginning all the world was America,” both Smith and the Puritan patriarchs of New England beheld the region as what England had been in the beginning: a fertile and wooded land waiting to be transformed by industrious English people into a productive pastoral civilization.7 Of course, the Puritans decidedly inflected Smith’s earthly vision of New England with a religious ideology that, among other things, saw the region as the home of the New Israelites—a remnant of the Godly elect.

“Now this part of America[,] New England,” Smith observed after his first trip to the region, “hath formerly beene called Norumbega.”8 Primarily a French cartographic invention of the sixteenth century, Norumbega had been conceived as both a city of fabled riches—a North American El Dorado—and a broad area that encompassed what would become Smith’s New England and that, European fancy speculated, contained fertile land, precious metals, and perhaps the fabled Northwest Passage. The mythical Land of Norumbega lingered in the European imagination as England finally awakened in the late sixteenth century to the promises of New World colonization. But Norumbega barely survived the transition to the seventeenth century, and by the time of Smith’s first voyage in 1614 the region he denominated New England was more commonly identified by the English as Northern Virginia, a vague geographic delineation that lay bare the limited knowledge of the area in England.9

In 1616 Smith published his influential Description of New England, a promotional account of his coastal voyage between Monhegan Island and Cape Cod two years earlier. With “New England” Smith completed the displacement of Norumbega and proclaimed that colonization would require effort, not the easy exploitation of a paradisiacal land. New England also supplanted the designation Northern Virginia, erasing any association between colonization in the north and Smith’s disastrous experience with English settlement in the south. For from its establishment as a colony in 1607, Virginia had been promoted as a new England—a “Nova Britannia.”10 But instead of the industrious English settlers whom Smith now envisioned for New England, Virginia had attracted gentlemen and ill-prepared adventurers who expected easy riches. Smith had moved to impose order and work discipline on the Virginia settlers only to be driven from the colony in 1609.

Smith’s ordeal in Virginia shaped his promotional image of New England, as did the failure of the first English attempt to colonize the region. Sagadahoc, a commercial beachhead with vestigial Norumbega-like hopes of material wealth, was established on the Maine coast in 1607. Poor leadership, economic disappointment, and a severe winter doomed the settlement. In less than a year Sagadahoc collapsed, bequeathing the impression that the region, far from being a mythical land, was a “cold, barren, rocky, Desart” inhospitable to English colonization.11

Smith confronted and attempted to deflect the legacy of Sagadahoc. The Maine coast, he allowed, “is a country rather to affright than delight.” Casting an eye past numerous islands to the coastal “main,” from which the area would acquire its name, Smith suggested that beyond “this spectacle of desolation” fertile valleys might lay in the interior. Still, he reminded his readers, “there is no kingdom so fertile [it] hath not some part barren and New England is great enough to make many kingdoms were it all inhabited.” South of Maine, in the land of the Massachusetts tribe, Smith located “the paradise of all these parts.” Here, where he saw a resemblance of the coast to Devonshire, Smith imagined the creation of a productive English shire. The territory offered not just fertile soil but impressive stores of fish and timber, all enhanced by the “moderate temper of the ayre.” Smith imaginatively assimilated the landscape of his New England to the geography of the homeland, he represented the region as a primitive England, and he exemplified the convention of overstatement that was the staple of promotional literature. “And of all the foure parts of the world that I have yet seene not inhabited,” the well-traveled captain enthused, “could I have but meanes to transport a Colonie, I would rather live here [New England] then any where.”12

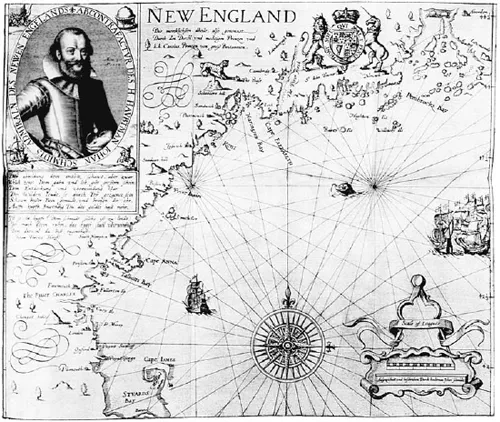

Smith included in his Description of New England a map that projected the region as a cultural annex of the homeland (Figure 1). Smith’s map substituted English toponyms for Native American place-names. Some of these names, such as the Charles River, Cape Anne, and Cape Elizabeth (all chosen by Prince Charles, the future king, in honor of members of the royal family), survived subsequent colonization. As one historical geographer has argued, naming a colonial land is among the first acts of imperialism: “In common with planting the flag or raising the cross, rituals of possession were enacted on innumerable occasions along the shores of America. Naming the land was one such baptismal rite for European colonial societies in the New World.”13

During the fifteen years between the publication of the Description of New England and his death in 1631, Smith remained a devoted publicist for the colonization of the region. He reissued the Description and published other tracts that advocated the creation of a “new” England.14 To promote interest in colonization, he continued to represent the landscape in ways that reassured prospective English migrants. His promotional strategy also accented the economic promise of New over Old England. “For I am not simple, to thinke,” he wrote, “that ever any other motive than wealth, will ever erect there a Commonweal; or draw companies from their ease and humours at home, to stay in New England to effect my purposes.”15 Smith, to be sure, miscalculated. His New England, as well as the cartographic and cultural Anglicization of the region that accompanied his promotional vision, served as the prelude to towns and colonies established by English religious dissenters. The most important dissenting group, the Puritans, fled to New England in pursuit of a purified, even primitive Christianity that derived from the restorationist aspirations of the Protestant Reformation.

FIGURE 1. John Smith, “New England” (1616, 1635). “New England” originated as a cartographic and promotional idea publicized by Smith. This is a 1635 version of Smith’s map, which first appeared in 1616. Courtesy of the Osher Map Library, University of Southern Maine.

Still, it would be misleading to suggest that the Puritan colonizers of New England inhabited a dualistic universe that separated the sacred from the secular, religion from economics. To the Puritan settlers who created a new England on the ground and not just in print, work, improvement, and productivity acquired moral status; economic activity became a way of glorifying God. Smith conferred with John Winthrop before the Puritan leader set sail for New England. Not surprisingly, in his Advertisements for the Unexperienced Planters of New England, or Any Where (1631), Smith expressed his hope for the Puritans, who “adventure now to make use of my aged endevours.” Unlike the Virginians of his earlier experience, Smith saw the Puritans as the embodiment of “Industry her selfe.”16 Much of their intellectual industriousness would be devoted to explaining New England to outsiders—and to themselves.

To be sure, the Separatists who established Plymouth Plantation preceded the Puritans by nearly a decade. The Plymouth Separatists would be renamed and mythologized in the nineteenth century as the “Pilgrim Fathers” of New England and America. The Pilgrims would become central to a much later imaginative construction—a reinvention of regional identity. But though the Separatists established the first permanent colony in New England, they hardly exerted the cultural effort required to achieve imaginative mastery of the region as a second England. In contrast to the Puritan settlement of New England, Plymouth was a small plantation with the Separatists a minority even at the start. Of the 102 passengers on the Mayflower, only 40 were Separatists. The others, including Miles Standish and John Alden, who became legendary figures in the nineteenth century, were “strangers,” secular-minded individuals hired for military or economic purposes. Many of the Separatist minority had already rejected the homeland for Holland. Though the sectarian planters of Plymouth read and were influenced by Smith’s writings, they seemed not to share his imperial vision of New England or the transatlantic reformist aspirations of the Puritans’ New England. Indeed, the Mayflower Compact—the agreement enacted by the Separatists in 1620 to establish and submit to laws and ordinances—referred to colonizing “northern Virginia.” Moreover,in an important tract, Reasons and Considerations for journeying to America, one Plymouth religious leader wrote that “we are all in all places strangers and pilgrims, travelers and sojourners, most properly, having no dwelling in this earthen tabernacle; our dwelling is but a wandering, and our abiding is but a fleeting, and in a word our home is nowhere.”17

Though the founders of Plymouth subsequently used the name New England, the small plantation acquired neither the intellectual leadership nor the commitment to literacy and education that were so pivotal to the Puritan fashioning of regional identity. Plymouth did not have an ordained minister until 1629, and it would be decades before Plymouth claimed its first graduate of Harvard, the Puritan college founded in 1636. Plymouth’s early historical importance stems largely from the support, particularly foodstuffs, that it furnished to the shiploads of Puritan migrants who arrived in the region in the 1630s.18 In contrast to the early Separatists, these nonseparating Congregationalists began to domesticate and dominate their new world by imagining it as a second England.

Until recently, historical scholarship on the founding of New England has tended to stress how the New World environment challenged and ultimately eroded inherited patterns of thought and action. Such a line of analysis may reflect the abiding influence of a frontier model of American historical development that has emphasized the “experimental, adaptable, and innovative” features of pioneering settlements in the nation’s past.19 The founders of New England quickly established decentralized civil, religious, and military institutions that grew out of the new context of their lives. Local self-government, covenanted churches that required a testimony of spiritual conversion for membership, town-based militia— these and other seeming innovations suggest that the doctrinally rigid Puritans adapted to New World circumstances.

Yet recent scholarship documents persuasively that though significant adaptations were made over time, the founding generation saw itself as a “transplanted English vine.”20 Wherever and whenever they could, first-generation Puritan New Englanders reaffirmed loyalt...

Table of contents

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Dedication

- Table of Figures & Table

- Preface

- Introduction: Region and the Imagination

- Chapter 1 - The Founding Generation and the Creation of a New England

- Chapter 2 - From the Americanization to the Re-Anglicization of Regional Identity, 1660–1760

- Chapter 3 - Regionalism and Nationalism in the Early Republic: The American Geographies of Jedidiah Morse

- Chapter 4 - Greater New England: Antebellum Regional Identity and the Yankee North

- Chapter 5 - Old New England: Nostalgia, Reaction, and Reform in the Colonial Revival, 1870-1910

- Chapter 6 - The North Country and Regional Identity: From Robert Frost to the Rise of Yankee Magazine, 1914-1940

- Epilogue: Toward Post-Yankee New England

- Notes