![]()

Chapter 1: Turkey and a Neo-Ottoman World Order

History as Ethno-imperialism

I arrive at the Türk Şehitlik Mosque on a midweek afternoon. Airplanes thunder overhead; a strange, empty wasteland seems to stretch before me as I walk along the long, deserted avenue. I do not realize on that summer day that airplanes will provide a motif for a study that will traverse the Middle East, Europe, and the United States. The airport looms behind me and, ahead, the old Muslim cemetery; both spaces are unsuitable for inhabitation yet promise transportation to better destinations. A white minaret pokes through the gray sky, followed soon after by an imposing dome, topped with a glinting metallic finial. A bus stop and parked cars obstruct the view through the walls of the Şehitlik Mosque, located directly on the busy Columbiadamm thoroughfare.

The area around the mosque is not built up, at least not in any memorable way. Its proximity to the airport makes it an undesirable residential location. The entrance comprises a small gateway with a large green sign announcing the Berlin Türk Şehitlik Camii (The Turkish Martyrs Mosque, Berlin). The courtyard is made up of a small graveyard and a paved area where a Ping-Pong table sits invitingly. Directly in front of the entrance is a low administrative building, and on the left a monumental structure in the form of an Ottoman mosque.

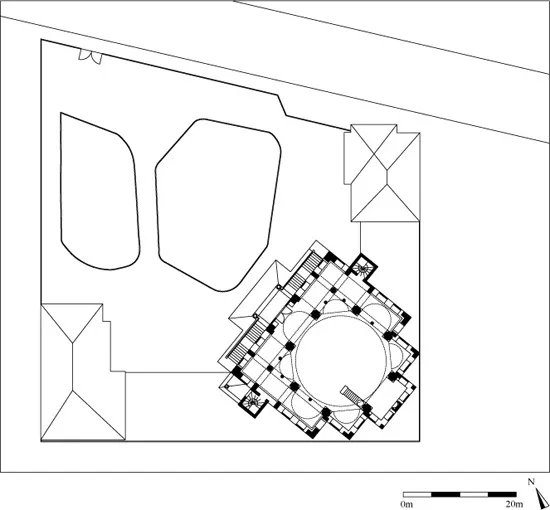

The bright white mosque sits serenely under the German sky, marking its presence as a highly charged political and religious symbol. Sited in the direction of Mecca, the plan of the mosque breaks from the urban grid, creating its own orientation. With its slate dome and towering pencil minarets, the mosque resituates the visitor not in the drab Kreuzberg neighborhood of Berlin, but on the sunny hills of Istanbul, reminiscent of the imperial glory of its Ottoman rulers.

Diaspora and Turkish Patronage in Germany

The twenty-first century is conceived by the Turkish Republic as its own, in terms of both political influence and economic prosperity. Expanding its global reach from Turkmenistan to Washington, DC, the country serves as a patron, an ally, and a negotiator between diverse religious and ideological spheres. Its diaspora has an important presence in countries such as Germany, and its entrepreneurs and labor forces are helping to develop the industries of several post-Soviet republics in Central Asia. Diplomacy and power are wielded through several means, foremost among them the patronage of cultural institutions. Mosque building, in particular, has been an important tool for the current government, whose Islamist links are a source of pride as well as condemnation in Turkey itself. The neo-Ottoman style of these mosques may be viewed as a reflection of the country’s expansionist ambitions, or as the recuperation of a past severed in the secularization movements of the twentieth century. Both interpretations would be correct; however, their significance depends on the specific geographical and nationalist contexts.

The Şehitlik Camii, or Martyrs Mosque, is located in an area of Berlin primarily populated by Turkish immigrant communities (fig. 1.1). The immediate location served as a Muslim cemetery for almost two hundred years prior to the construction of the new mosque. According to the history of the Friedhof neighborhood, the Ottoman intellectual Ali Aziz Efendi had been a guest of the King of Prussia and, on his death in 1798, was buried in a plot of land in Tempelhof.1 Thus Berlin was the location of Turkish migration from at least the late eighteenth century, when political relations between Berlin and Istanbul had already been established.2 Turkish guardsmen had been part of the entourage of the Prussian rulers, and it was for them, initially, that the Muslim cemetery and mosque was built, in 1866.3 The land was enlarged in 1921 to accommodate Turkish soldiers who had come for treatment to Germany during World War I, when the two countries were allies. The cemetery is now further expanded and contains the graves of not only Turks, but Muslims from all over the world.

FIGURE 1.1. Türk Şehitlik Mosque, Berlin, completed in 2005. Architect, Hilmi Şenalp. Photograph by the author.

The cemetery was originally entered through an ornate gateway and is reminiscent of Andalusian architecture that exemplified the “Moorish” style popularized by Europeans at the turn of the twentieth century.4 Behind the impressive gateway was an unassuming building that served as a mosque and hall for carrying out ritual activities. The modest space was in keeping with the small population of Turks and Muslims in Berlin at that time.5 A short minaret was attached to the building, and a small dome rose over the main prayer space. The land was later purchased by the Turkish government, which continues to be the primary patron of the Şehitlik Mosque.

In the second half of the twentieth century the political situation of Berlin changed drastically with the division of the city between East and West Germany. Labor shortages made it necessary for the government to establish programs for short-term workers to move to West Germany (known as the Federal Republic of Germany from 1949 until reunification in 1990). The demographics of the city changed, too, with an influx of migrants from Central and Eastern Europe as well as Asia. In 1961 West Germany signed a labor treaty with Turkey that would bring in guest workers (Gastarbeiter) to perform skilled and unskilled labor in its postwar reconstruction. Berlin, due to its bifurcation, was particularly hard pressed for cheap labor, and its Turkish community was among the largest in the country. However, the assumption that the guest workers would eventually leave was misplaced. Over the following decade, until the treaty ended in 1973, Turkish men immigrated to Germany, bringing with them wives, parents, and other family members.6 The demographic shift was so profound that a 2010 census counted at least 4 million people of Turkish descent living in Germany. Social and economic disparities have made the relationship between Germans and their “guest workers” far from equitable or harmonious, even though Turks have finally been allowed greater rights and—finally—citizenship.

Mosques serving the Turkish community in Germany are overseen by the Religious Affairs Ministry in Turkey itself. The Şehitlik Mosque is funded and overseen by the Diyanet İşleri Türk İslam Birliği (

), or Turkish Islamic Union for Religious Affairs. As the immigrant population in Berlin grew, so too did the need to create an appropriate space of worship for the Turkish-Muslim community. In 1996

commissioned a new mosque, to be constructed in the Şehitlik cemetery and designed by the Turkish architect Hilmi Şenalp, known for his neo-Ottoman-style mosques. According to the designer’s website, the foundation stone was laid in 1999 and the mosque was completed in 2005. The building occupies approximately 1,360 square meters (14,639 square feet), and there have been plans to expand the complex to include a cultural center.

7The Şehitlik Mosque is in the form of a modestly scaled Ottoman mosque, with a monumental dome flanked by two tall minarets (fig. 1.2).8 The dome covers the centralized prayer space, its drum perforated by windows to bring in natural light. Semidomes cascade down from the drum, marking the zone of transition from the spherical dome and cubic base. The minarets are in the “pencil” form typical of the Ottoman period, with striations on the sides that accentuate their slender height. An overhanging eave and graceful portico shelter a pair of stairways leading up to the prayer hall. Ornately carved wooden doors remain open at the entrance, their geometric patterns echoing the decorative motifs found inside.

The interior of the mosque contrasts with the solidity and mass of its exterior (fig. 1.3). Here the white paint is highlighted by floral, turquoise wall paintings (replicating the mosaics of Ottoman structures) and ornate epigraphic bands in dark blues and gold. The multiple arches comprising the ceiling structures are framed in ablaq-technique red, black, and white bricks, lending a colorful harmony to the space within. This technique of bichrome masonry was popular in early Islamic architecture and is associated with great mosques from Cordoba to Istanbul. Between the arches are large epigraphic medallions featuring the names of Muhammad and his companions, the proceeding four caliphs of the early Islamic community. White muqarnas (stalactite) details on prefabricated stucco replicate the intricate workmanship of Islamic art, as do the luminous colored-glass windows, which add a rich glow to the space within.

FIGURE 1.2. Schematic plan, Türk Şehitlik Mosque, Berlin. Drawing by Mahdi Sabbagh.

The apex of the prayer hall is the domed ceiling, decorated with a colorful medallion in traditional Turkish floral and geometric motifs. The 112th chapter of the Qur

an, the Surah

al-Ikhlās (Fidelity), is inscribed in the center of the medallion. The short chapter, comprising only four phrases, expresses the foundational aspect of Islamic belief, namely the unity and singularity of Allah.

9 This is not a common verse for inclusion in architectural epigraphy, perhaps owing to its brevity. But in the Şehitlik Mosque

the master calligrapher Hussein Kutlu has magnified it to make it legible from below. The 24-karat gold used in the epigraphy contrasts with the black background on which is placed. The gilding and wall paintings were executed by the master painter (

naqqāsh) Semih Irtes.

10 Kutlu and Irtes are established artists in Turkey, renowned for their skills in traditional design and rendition, respectively.

11 Their selection for this project points to the significance of the mosque both to the local community and the Turkish government.

FIGURE 1.3. Interior, Türk Şehitlik Mosque, Berlin. Photograph by the author.

The focus of the mosque is the mihrab niche within the qibla wall. On either side of the mihrab are two windows with arched epigraphic panels in Iznik-inspired tilework (plate 3). Just above the mihrab is a gilded panel that reads, “Turn then thy face in the direction of the Sacred Mosque (

al-masjid al-ḥaram).” On the qibla wall, above the mihrab, is a band of epigraphy with the last half of the Throne Verse (

Ayat al-Kursī): “Nor shall they compass aught of His knowledge except as He willeth. His Throne doth extend over the heavens and the earth, and He feeleth no fatigue in guarding and preserving them. For He is the Most High, the Supreme (in glory).” The expansive language of the Throne Verse makes it a popular choice in mosques and it holds special meaning when the mosque

is located in a non-Muslim country. On the panels above the windows are verses from the opening chapter of the Qur

an,

al-Fatiḥa (the Beginning).

12 These, too, are standard verses that would be easily recognizable to those with knowledge of the basic tenets and practices of Islam. As such they serve a broad community of believers, although it is not clear how many of the Turks patronizing the Şehitlik Mosque would be able to read the Arabic script. As part of their educational mission, the mosque administration provides classes in which young children and adults are taught enough classical Arabic that they can read and recite the Qur

an. The epigraphy on the walls, written in a legible and monumental script, serves as an intriguing reminder to the Turkish visitors of their Islamic heritage.

The historical emphasis of the Şehitlik Mosque is not without coincidence. The choice to build a mosque in the style of the Ottomans thus marks both the long presence of Turks in Berlin and the pride that that community has in its imperial heritage. Under the aegis of

, it is also overlaid with a religio-political identity. The Cologne-based organization was founded in 1984 as an outpost of the Turkish government, mandated to oversee the merging of the Turkish Republic’s religious and secularist ideals.

is thus the patron to numerous mosque construction projects, with a focus on serving the community by educating them about immigrant rights and integration.

13 As is apparent from its website, one of the primary functions of the organization was, and continues to be, the establishment of clubs for activities as diverse as religious education and sports. The website boasts that t...