![]()

CHAPTER ONE

The Model City

A Romance of the New South

There is no other place in the Southern states so healthy, so beautifully situated, none where the air is purer, the water clearer, and where there are so many pleasant inducements to the full enjoyment of these luxuries of life. —Atlanta Constitution, 1883

An 1883 display ad in Henry Grady’s Atlanta Constitution proclaimed Anniston the healthiest place in the southern states. The “Best, Healthiest, and Most Invigorating Climate in the World” claimed the city’s founders and publicists. In Anniston could be found the “Three Essentials of a Good Home: Pure Air, Good Water, and a Salubrious Climate.” Nature itself invited industry, the city’s promoters implied. “Nature favors them marvelously,” wrote the New York Times. The Baltimore-based Manufacturers Record, an industrial journal, boasted in 1889 that Anniston’s “mountain air and pure water . . . insure the health and comfort of the workman and his family; . . . stimulate and lighten labor” and not only “enabled Anniston’s citizens to create her past and present prosperity” but also would “secure her future.”1

The story that leads from this nineteenth-century portrayal of Anniston as a healthful Eden past its twenty-first-century designation as “Toxic Town, USA” is neither uncomplicated narrative of adversity overcome nor simple chronicle of environmental decline. Not a few of the conditions that permitted the Monsanto Chemical Company to keep discharging toxic chemicals in West Anniston for so long were embedded in a set of natural resource regimes, economic structures, and attitudes toward race and the health of the laboring classes that had been in formation since the town’s founding in 1872. When in 1935 the Monsanto Chemical Company in St. Louis absorbed one of its largest competitors in the South—the enterprising north Alabama chemical firm named for its flamboyant owner, Theodore Swann—the company profited from more than a half century of southern industrialization and militarization. Theodore Swann’s biographers concluded that Anniston was “an unlikely setting for the events that occurred,” but, for its purposes, Monsanto had chosen well. Beyond the obvious benefit of consolidating its hold on a competing chemical producer in a resource-rich region of the South, the company-town origins of Anniston must have appealed to Monsanto. In its various expansions, Monsanto often eponymously named (or renamed) the entire surrounding town—as in Monsanto, Illinois; Monsanto, Idaho; and Monsanto, Tennessee. Significantly, Anniston kept its own identity.2

WHEN IRON AND MUNITIONS MANUFACTURER Samuel Noble visited north Alabama in 1869 via steamer down the Coosa River from Rome, Georgia, he found “a literal mountain of brown hematite ore, with heavily wooded foothills, guarding the entrance to a valley of surpassing beauty.” A few years later, Noble brought former Union general Daniel H. Tyler to explore the terrain on horseback. General Tyler had experience in iron manufacturing and, as important, had amassed considerable wealth investing in railroads. (The Tylers were also well connected; General Tyler’s granddaughter married Theodore Roosevelt in 1886 and served as first lady from McKinley’s death until 1909.) Roaming the Alabama hillsides piqued his interest in Noble’s proposal for a new proprietary town.3

For three days in the spring of 1872, the pair surveyed the iron-rich outcroppings amid the longleaf pines. Each night, the men rode two miles south to a hotel in Oxford and, sipping the aging general’s favorite Chinese green tea, discussed their plans. In a vast, shallow bowl of Alabama clay between the verdant, low mountains, they would build a model city. The primary industry—iron manufacturing—would tap the unexploited mineral resources that lay barely beneath the surface of the soil. Nature would be the instrument for realizing their dreams.4

Geologic forces had deposited Alabama’s iron riches during the Silurian Period, more than 400 million years earlier. A vast underwater manufacturing process took place in these swamps during the Paleozoic Era, producing high-quality coal. As the master continent, Pangaea, formed during the Pennsylvanian Period, “Alabama was at center stage in this geologic spectacular,” one Alabama geologist explained. The ecological assets that launched north Alabama’s industrial experiment with iron manufacturing would profit the chemical industry as well; coal tar, a coal by-product, would form the basis of many synthetic chemicals.5

One of the southernmost counties in the Appalachian range, Calhoun County lies close to the border of the Piedmont plateau, in the ridge and valley region of this Deep South state. The Coosa River, which forms the county’s western border, winds its way from north of Rome, Georgia, to the Alabama River and the Gulf of Mexico. Like New England and the western territories, the land was often described in gendered metaphors, as “part a barren field, and part a virgin forest,” inviting man’s intervention, but this had long been a working landscape. From the earliest “Flush Times” in 1830s Alabama, a devil-may-care approach to resource use prevailed. The area had “every natural advantage,” Noble recognized, though “it had long been gashed and starved by man.”6

Virtually all of the Creek Indians had been driven out in the 1830s. Sally Ladiga, widow of Creek Chief Ladiga, sued all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court to win recognition of her right to remain. By 1840, however, the erasure of Native Americans from this territory was all but complete. Their legacy lingered in place names such as Choccolocco Creek, translated as “Big Shoals,” for the wide, flat, stony sections of the waterway.7

Alabama’s state geologists not only mapped Alabama’s resources but also aggressively marketed them to outside investors. The state’s underground wealth held “deposits tempting in their abundance and unique in their combination.” The geological riches seemed inexhaustible. “A century of labor would not begin to impoverish this mighty depository,” early boosters believed.8

The north Alabama hill country had both coal and iron “in unexampled proximity.” The 110 acres Samuel Noble purchased in 1869 for the hefty price of $6,000 contained prime woodlands and ores. Within easy distance of Noble’s tract were all the necessary products for making iron: rich ore outcrops, limestone, and the coal fields and dense pine forests that provided the fuel for industrial development. At the time, Alabama was already first among southern states in iron production and fourth among iron-producing states nationally.9

Anniston’s founding families came to Calhoun County in 1872 to construct a profitable Eden. The founders envisioned a unique experiment, an exceptional city in a distinctive region. Anniston would be a willing partner to modernization within the reluctantly reconstructing South. The Nobles and the Tylers first established the Woodstock Iron Company in 1872 as a private town. (Another Alabama town was called Woodstock, so they named the city for Anne Scott Tyler, wife of the general’s son, Alfred Leigh Tyler, in recognition of her key role in securing additional capital through family ties with a New York financier.) At the town’s official opening to the public in 1883, Atlanta newspaperman Henry Grady, the most prominent spokesman for an urban and industrialized New South, declared the vision realized, dubbing Anniston “the Model City of the Southern States.”10

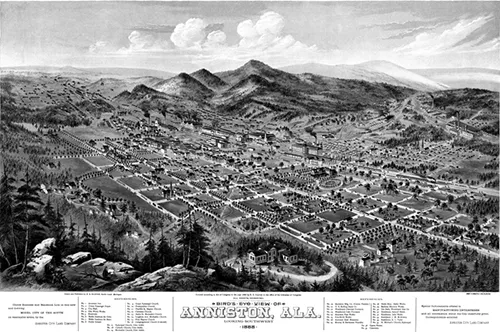

“A Bird’s Eye View of Anniston, Ala.” (1888). Artist’s rendering of the industrial town of Anniston, “the Model City of the South.” Looking southwest, the smokestacks of the industrial district and Coldwater Mountain are in the distance. The founders’ residences occupy the left foreground; the “Colored” Congregational Church lies at right, within a few blocks of the Woodstock Coke Furnaces and the Anniston Pipe Works. Drawn and published by E. S. Glover; printed by Shober & Carqueville Litho. Co., Chicago.

THE NORTHERNMOST COUNTY in Alabama to have voted in favor of secession, Calhoun County’s name revealed its strong sectional loyalties. Originally known as Benton County, the Alabama legislature renamed the county in 1858 for a foremost proslavery secessionist, Senator John C. Calhoun of South Carolina. Built after the Civil War, Anniston was put forward as a place that would escape what C. Vann Woodward termed “the burden of southern history,” marked by slavery and defeat. The new city’s leaders aimed to set the town apart not only from the slums of the industrialized Northeast but also from the inhumanity of southern plantation slavery.11

The relationship between Anniston’s founding families has often been portrayed as a symbol of sectional reconciliation between a Confederate arms manufacturer (Noble) and a Union general (Tyler), “a Connecticut Yankee with capital.” Typical in this regard is the Federal Writers’ Program volume on Alabama, published in 1941, which said of Anniston: “Not the least unusual part of the story of the founding of the town is the fact that men of such widely divergent backgrounds, with Northern and Southern affiliations, were able to unite in the enterprise so shortly after the War between the States.”12

The North-South reconciliation narrative made a good story: an unlikely economic partnership overcoming wartime differences and yielding mutually beneficial industrial development. In fact, neither man was a southerner. Noble was an Englishman by birth; his sectional loyalties derived mainly from a desire “to associate with the region from which he derived most of his trade.” (Noble’s journey south from Pennsylvania in the mid-1850s included one notable misadventure. On the way to Rome, Georgia, he shared a car with Jefferson Davis and, not recognizing the then secretary of war, had him arrested—mistakenly it turned out—for the theft of a carpetbag containing $4,000.)13

Anniston stood at the center of a battle waged by competing railroad magnates for political and economic control of Alabama. The white supremacy candidate for governor in 1874, Democrat George S. Houston, won the fight by a substantial margin. Setting a pattern that would remain durable and leave state coffers impoverished, Governor Houston imposed generous tax exemptions for railroads and other corporate interests.14

Railroads made possible the intense exploitation of the forest resources that powered the commercial production of iron in north Alabama. (The few local laws governing conservation in this period were passed for industry’s benefit. Anniston regulated tree cutting to preserve fuel for the city’s herbivorous furnaces.) The two enterprises were mutually dependent—railroads required iron, and iron manufacturers needed dependable transportation. Iron riches and reliable rail transport eventually made Anniston “the soil pipe capital of the world,” connecting the city’s sewer pipe factories to distant markets around the globe.15

Over time, the railroad itself defined racial spheres. Rail travel contributed to newfound black mobility, spurring white fears of “racial pollution,” of breaching racial hierarchies.16 Train tracks also often separated the wealthy white residential sections of town from the ones that housed poor whites, African Americans, and polluting industries. On railcars and at railroad stations, barriers to racial interaction would not be broken until black and white civil rights protesters took direct action, at Anniston and elsewhere, almost a century later.

Violence both maintained racial inequality and retarded industrial development. Not long before Anniston’s founding, one of the largest mass lynchings in Alabama occurred in northern Calhoun County, where in July 1870, Klan marauders murdered seven men. The lynchings revealed the fragile limits of former slaves’ newfound freedom, targeting black mobility, Reconstruction hiring policies, and black education. The events, which Anniston newspaperman Harry Mell Ayers later described as a “lynching bee,” led New York financier John Jacob Astor to cancel plans to build a new industrial town near Cross Plains, now Piedmont.17

In contrast to the violence at Cross Plains, the Nobles and the Tylers built Anniston “according to the doctrine of the Episcopal Church and the platform of the Republican Party.” In Anniston, the new order would be healthy, orderly, and civil. The founders invested in the social, educational, and cultural infrastructure of the town, priding themselves on its theater, shops, and schools. Publicists’ rhetoric emphasized that concern for factory workers’ health distinguished Anniston from the urban, industrialized North, contrasting the company town’s “pretty cottages” and “vine-covered porches” with northern tenements rife with “discomfort and disease.” One promotional brochure declared, “The pale, pathetic faces, with their weary, timid look, so often seen in great manufactories, are unknown in this place, where air and exercise, clean houses, pure water and wholesome food are afforded to all.”18

The Colored Congregational Church in Anniston housed the school for children of the formerly enslaved, which was “second probably to no other of that class in the state of Alabama,” wrote General Tyler. “We have done all we could,” said Tyler, “to invite into our company the best class of labor, white or black, that we could obtain, and to give to their children such an education as would elevate them, if possible, in their future careers.”19

The Model City rhetoric masked the contrast between a spoken reverence for human and natural resources and industrial practices that exploited both. In the model town, the rights of both African Americans and the white laboring population were carefully circumscribed. Anniston’s founding families would later be described not only as “visionaries” but also as “oligarchs.” Town governance left little room for dissent. Southern historian Woodward later singled out the city as “the very [arche]type of industrial paternalism.” The town’s founders promised pay and amenities slightly higher than the state average; in exchange they expected from workers loyalty and strict adherence to discipline. “We made up our minds that, in order to get good labor, it must be paid for liberally,” General Tyler explained, “believing that it was our duty to give them the means of making a comfortable living, in order to exact from [laborers] a...