![]()

Part One

Conus

![]()

Two

The Selection Process

The early years of the Vietnam War found the military in a healthy position regarding the prospects of officer procurement. President John F. Kennedy’s stirring words that “the torch has been passed to a new generation of Americans . . . [and] that we shall pay any price, bear any burden, meet any hardship, support any friend, oppose any foe, to assure the survival and the success of liberty”2 inspired many young men to seek employment in their government, some in agencies such as the Peace Corps and others in the military. When the events associated with the Cuban Missile Crisis caused Congress to reinstate the draft for the first time since the Korean War, many young men accepted their plight and entered the army almost willingly because it was their duty as citizens. Hostilities in Vietnam in October 1962 were minimal, although 16,000 Americans were serving there as advisors, and casualties were “light.”3 Most of the officers had been commissioned through the USMA or through ROTC programs at military-oriented schools such as the Citadel, Virginia Military Institute, or Texas A&M University. In general, the army had no officer procurement problem.

When the marines went ashore at Da Nang in March 1965, followed in May by the army’s 173rd Airborne Brigade, army personnel officers recognized immediately that supplying junior officers to the combat arms would be a major challenge. The generals who commanded corps and divisions were sufficiently in the pipeline, as were the field-grade officers who commanded battalions and brigades. Many of these majors, lieutenant colonels, and colonels had combat experience from World War II and/or Korea, and they were considered by the military establishment to be sufficiently trained and ready to command troops on the battlefield. But lieutenants and captains, who would command platoons and companies in combat, were in short supply, and there was no immediate solution. The USMA could be expanded, but even if the input were doubled, which ultimately was accomplished, such officers would not be available for platoon duty until 1969. The ROTC programs could be expanded, and new programs could be launched at schools where none had previously existed, but that would also take years to achieve. The only flexible avenue for increased officer commissioning was through OCS, and most such schools had been severely curtailed after the Korean War.

The need for junior officers was paramount in the minds of the various chiefs of staff when they met with President Lyndon B. Johnson in early November 1965 to propose an alternative battle plan to that being suggested by Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara. This plan, to take the war to Hanoi and Haiphong in North Vietnam through the use of air and naval power, was endorsed by all of the chiefs as well as by the chairman, General Earle Wheeler, but was soundly rejected by President Johnson.4 This critical meeting launched the decision to rely on ground troops to win the war and was crucial to the issue of manpower planning. Consequently, one can conclude that it was in early November 1965 that the army had to develop plans to fill the junior officer leadership vacuum.

The most obvious solution to the officer shortage would have been a call-up of the reserves and/or the National Guard. Units could have been activated that were capable of being deployed immediately for Vietnam. But the issue of whether, when, and what units to call would cause controversy within the Johnson administration from the buildup through the TET Offensive period. In the early days, Chairman Wheeler opined that calling up the reserves would not be efficient, because reserves could not be moved into combat in ninety days, as had previously been announced, but instead would take four months. Given such a choice, the war managers opted for the use of new troops, some of whom would be draftees, since they could also be trained and made combat effective within the same four months.5 Gen. William Westmoreland also believed that a call-up was not necessary, because enabling legislation would be required if the reserves were to be deployed for more than one year.6 President Johnson also resisted, citing the strong pressure to cancel the call-up during the recent Berlin crisis and knowing that political pressure would come to bear on the administration once the war began to affect those who had volunteered to serve in capacities that did not include Vietnam. Thus the general backed the president, ostensibly against the wishes of the secretary of defense, and the draft or the threat of conscription would supply the soldiers that junior officers would lead into battle. Further compounding the decision process was the fear that company-grade officers within these potentially called-up units might not be capable of leading men in combat and, in some cases, were not even occupying positions commensurate with their Military Occupational Specialty (MOS).7 Thus, for a variety of reasons, most of which were political, reserve units were never called up for combat duty, though certain MOS needs were eventually met by activating soldiers with certain required skills.8

The army was faced with filling the pipeline with junior officers who could quickly assume combat leadership roles. To the army’s credit, even with a war raging and with personnel needs paramount, it recognized the need to procure as many junior officers as possible who were college educated, or who at least had some college background. The army looked to the campuses across America to meet its needs, either through existing ROTC programs or through the recruitment of college students into the planned expansion of OCS. But the college campuses were teeming with antiwar sentiment.

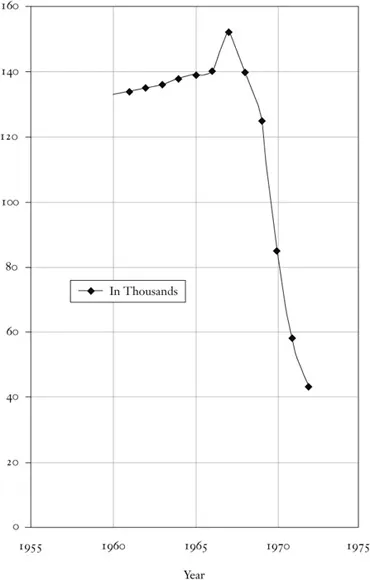

Figure 2.1 illustrates ROTC enrollment on college campuses across America. At the time of the buildup, there was minimal visible unrest on college campuses, although that would change dramatically as the war intensified. Furthermore, since college students were exempt from military service (2-S deferments) if they maintained satisfactory progress toward a degree, opposition to the war was based more on moral convictions than on fear of being drafted. However, in 1966 the Selective Service changed the rules and required male students who would otherwise be eligible for the draft in the absence of a 2-S deferment to take the Selective Service College Qualification Test to prove their ability to continue in college. If they wanted to attend graduate or law school, they were required to score exceptionally high on this standardized, nationwide exam. In 1967 Congress abolished graduate deferments except for medical fields and allowed student deferments only until completion of the bachelor’s degree.9 An implementing executive order provided a one-year deferment for persons accepted for admission into a graduate program or professional school for their first year of study beginning October 1967, and it authorized deferment of subsequent years within certain specified time limits.10

The military was clamping down on this easiest of all deferments, and campus unrest began in earnest across America. Although the antiwar movement was generally widespread, certain areas of the country were more bellicose than others. For example, after the TET Offensive in February 1968, protests against ROTC members and facilities took place at the University of Michigan and the University of Maryland, and ROTC buildings were burned at Howard University, the University of Wisconsin, and Michigan State University.11 Some schools even dropped their ROTC programs completely; Harvard, Dartmouth, Yale, Columbia, and Stanford were the most prominent.12 Other schools began to cancel their participation, not because of student protest, but because there were not enough cadets to maintain a viable program: small liberal arts colleges such as Franklin and Marshall, Grinnell, and Davis and Elkins fit into this category.13

Figure 2.1 ROTC Enrollment

SDS (Students for a Democratic Society) disrupts Cornell ROTC exercise, 1969 (photo courtesy of the Dallas Morning News Collection, Texas Tech University, The Vietnam Archive, VA014058)

With ROTC programs being curtailed, the army still maintained its desire to attract college-educated men to fill its junior officer ranks. Recruiters visited campuses to explain OCS options to students who might be facing induction or whose college had no ROTC program. In many locations, recruiters were not welcomed on campus. At Whittier College in California, an OCS selection team was heckled by several “hippie types,” and at Hamilton College in New York there was a lie-in by eighteen students.14 Outright bans on recruiting were instituted by Brooklyn College, Hunter College, Herbert Lehman College, and Queens College, all of the City University of New York. The letters to the army in these matters usually stated that while the administration understood the desire of the army to procure collegeeducated officers, the students and faculty chose to not allow recruiters on campus.15 Dr. Edwin D. Etherington, president of Wesleyan University in Middletown, Connecticut, wrote to the secretary of defense asking that military recruiters not conduct interviews or tests on campus but, rather, to schedule activities with Wesleyan students at sites off campus. He admitted in his letter that other government agencies and businesses would still be allowed to recruit on campus.16

Against this backdrop of campus unrest, the army had to address the problem of finding junior officers. An easy solution might have been to just expand OCS by sending existing enlisted men to such schools, but the records indicate that the army continued to actively seek college graduates. And since deferments had been tightened considerably, potential draftees sometimes sought refuge in army officer candidate schools, particularly during the period when a candidate could choose to enroll in a noncombat-arm OCS program. Such “reluctant volunteers” raised suspicions in the army as to the likelihood of a sufficient desire to obtain a commission.

The army was concerned enough about the motivation for entering service that it conducted a survey in 1969 to determine if the draft was the most compelling reason for enlistment. The study was conducted among soldiers in the United States, of all grades, both officers and enlisted men. Those surveyed were asked, Would you have entered active military service if there had not been a draft or military obligation? Response options were “definitely yes,” “probably yes,” “probably no,” “definitely no,” and “don’t know.” Among 1st and 2nd lieutenants, approximately 65 percent of those questioned answered “definitely no” or “probably no.” Even half of the captains who would have reenlisted to achieve their higher rank indicated that without the draft, they probably would not have volunteered. Equally significant were the results from enlisted men whose responses were identical to those of officers, up to the rank of E-6, when careerism set in.17 One can conclude, therefore, that the majority of the junior officers had joined the army for the same reason as had the men they would command: because their government would have forced them into service had they not enlisted.

The army was also interested in men who waited to be drafted, because this group was also a potential source of officers. The army commissioned a study of men who had been called to the Armed Forces Enlistment and Examination Centers for their first physical examination. Since these men had not yet made up their minds as to how they would handle their obligation, they provided the army with data necessary to effectively recruit them into active duty. For the army, the data was devastating. White, black, and “Spanish American” men all uniformly chose enlistment in the navy or air force before enlistment in the army.18 By ethnic group, 42 percent of whites, 37 percent of “Negroes,” and 35 percent of Spanish Americans were going to wait to be drafted.19 Among this group, 26 percent had some college experience, with 5 percent having graduated and 4 percent having done postgraduate work. As for the reasons these citizens chose not to volunteer, 35 percent of white respondents and 12 percent of Negro respondents indicated a desire to serve only two years instead of the necessary three associated with enlistment.20

These findings had a significant impact on the army’s plans for officer procurement. The recruiting study was commissioned in late 1967, just prior to the TET Offensive, and an early indication on the college student situation coincided ...