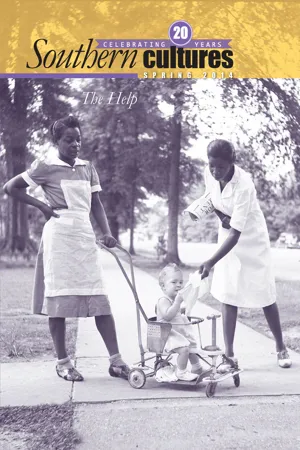

![]()

ESSAY

The Divided Reception of The Help

by Suzanne W. Jones

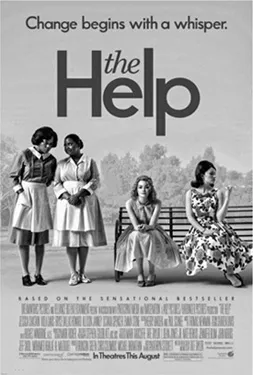

The Help was number one on the New York Times bestseller list for over a year after its publication in 2009. By the time the movie was released, the book had sold 3 million copies, spent more than two years on the New York Times bestseller list, and been published in 35 countries and translated into three languages. Three months after the film’s release, it had grossed $160 million at the box office. The Help movie poster, © DreamWorks Pictures, 2011.

The reception of Kathryn Stockett’s The Help (2009) calls to mind the reception of two other novels about race relations by southern white writers: Margaret Mitchell’s Gone With the Wind (1936) and William Styron’s The Confessions of Nat Turner (1967). Like Gone With the Wind, The Help has been a pop culture phenomenon—prominent in bookstores and box offices, and the “darling of book clubs everywhere.” In January 2012 when I asked students in my Women in Modern Literature class what was the best book they had recently read by a woman, most named either The Help or The Hunger Games. And not surprisingly. The Help was number one on the New York Times bestseller list for over a year after its publication in 2009. Similarly, the movie held the number one spot in box offices for several weeks after it was released in August 2011, thereby propelling the trade paperback back up the New York Times bestseller list, where it remained a year later. By the time the movie was released, the book had sold 3 million copies, spent more than two years on the New York Times bestseller list, and been published in 35 countries and translated into three languages. Three months after the film’s release, it had grossed $160 million at the box office. Both novel and film have been discussed in likely television venues, such as The View, as well as in unlikely ones, such as Hardball (Chris Matthews loved it). Add to that, DVD purchases, Netflix rentals, and e-books (one of the most downloaded e-books of all time), and readership and viewership of The Help may someday surpass that of Gone With the Wind. Readers from coast to coast made it the most checked-out book in the country for 2010 and 2011. Both novel and film were nominated for awards. The novel won prizes at home (BookExpo America’s Indies Choice Award, the Southern Independent Booksellers Alliance Award for Fiction, the state of Georgia’s Townsend Prize) and abroad (the UK’s Orange Prize, South Africa’s Boeke Prize, and the International IMPAC Dublin Literary Award). And director Tate Taylor received the Writers Guild of America, West’s Paul Selvin Award for his adapted screenplay. While The Help did not win the Oscar for best picture or Viola Davis for best actress, Octavia Spencer did win for best supporting actress, and the film “walked away with the most kudos at the 43rdNAACP Image Awards, taking home the top prize for outstanding motion picture and nabbing actress and supporting actress honors for Davis and Spencer.”1

But despite these accolades from both predominantly white and black organizations, Nkiru Nzegwu, the editor of JENdA: A Journal of Culture and African Women Studies, sees a black-white dividing line in the film’s reception: “White viewers see complexity where many black viewers see crass simplification. Whites believe they have finally grasped the existential pathos of black southern life in the 1960s but blacks beg to differ, pointing to the cavalier dismissal of white supremacist violence and the tone-deaf representation that fails to see or acknowledge their humanity, as well as refuses to grasp the manner in which white privilege is propped up by institutionalized racism and racial bigotry. Whites hope that The Help has revealed the common humanity of all, while African Americans fear that the crudely sketched images of themselves may end up reinforcing old stereotypes.”2

However, judging from viewers’ comments on polling websites, the reception of the film is not as polarized or predictable as critics of popular culture have imagined. Although many white viewers have “loved” the film, and no doubt for some of the reasons Nzegwu mentions, a good many white viewers have panned it, as Mary did on Amazon.com, “Sugary sweet, 3 hankie tear-jerker, crowd pleasing & deeply dishonest.” Judging The Help as “yet another entry to the Driving Miss Daisy genre of feel-good, simplistic examinations of topics that in truth are not easy, simple,” Mary goes on to say, “The solace I have, as I reflect on The Help, is that there WERE brave, noble white people who wanted to bring equality to The South: Andrew Goodman & Michael Schwerner. They didn’t end up at big jobs in NYC. They ended up dead.” This sentiment occurs frequently enough on these forums to suggest a deep desire, at least by some white viewers and readers, not to be seen as naïve or ignorant about the violence of the Civil Rights era, which figures only in the background of The Help, or about institutional racism, a subject Stockett does not take up. While many black viewers, as Nzegwu suggested, have found Stockett’s characters stereotypical and the portrayal of black life simplistic, many other African American viewers, like Minerva Bryant, have praised The Help as a revelation of the hardships of black domestics: “It is not a well kept secret, but this is the first time I can say the truth is being told . . . Yes, it may have taken someone from the other race to help ‘put it out there,’ but that was the instrument that opened the eyes of the world regarding the struggles of ‘colored’ maids/help. I thank God for ‘The Help,’ and the cast was SUPER!” Still other black and white viewers, much like Rashun, who is African American, viewed the film merely as “entertainment”: “I wasn’t looking for a lesson in race relations. I have a life experience of that from living and traveling in America and other places. The actresses in this movie made it good to me . . . Good stories and good performances.”3

While no doubt a larger percentage of white than black general readers and viewers have embraced The Help, it seems, at least from perusing comments on polling websites such as CinemaScore and Amazon.com, that praise for the film and the novel has definitely crossed racial lines. Both black and white general viewers have termed the film “excellent” and defended its limited focus on race relations in the domestic sphere, much as director Taylor did, as “the last remaining facet of the story that hasn’t been told.” Most general readers posting on Amazon.com and other websites have praised The Help as “one of the best books I’ve read in 2009—maybe the best,” and many are confident it will become “a classic.” Like several readers, S. J. Woolf-Wade would like to make the novel required reading, “All Americans need to read this book!” Still others, such as “tkmom,” feel the same about the film, “This is a classic which should be shown over and over again so that the youngsters of today can understand why people feel about others the way they do. This feeling is not limited only to African Americans but also to all races who are subservient to others.” The Help is most often mentioned by both black and white readers as “rivaling such treasures as To Kill a Mockingbird,” although almost as many other readers are upset that a novel they think of as popular entertainment is compared to one they consider great literature. None, however, seem aware of the recent academic debate swirling around the racial politics of To Kill a Mockingbird—from Eric Sundquist, who views Atticus Finch’s defense of Tom Robinson as southern incrementalism, to Christopher Metress, who argues that Harper Lee has embedded Sundquist’s very critique of Atticus in her novel.4

While The Help did not win the Oscar for best picture or Viola Davis for best actress, Octavia Spencer did win for best supporting actress, and the film “walked away with the most kudos at the 43rd NAACP Image Awards.” Viola Davis (standing, foreground), Octavia Spencer (seated, obscured), and fellow actors on set, 2010, courtesy of Lex Williams.

A more prominent dividing line in reader and viewer reception of The Help than race would seem to be between general audiences and academics. This division was forecast by the difference between the USA Today’s glowing review of Stockett’s “thought-provoking debut novel” (“one of the best debut novels of 2009”) with its “pitch-perfect depiction of a country’s gradual path toward integration” and Janet Maslin’s mixed response in the New York Times to what she termed a “problematic but ultimately winning novel,” “a story that purports to value the maids’ lives while subordinating them to Skeeter and her writing ambitions.”5 This divided reception recalls the reception of The Confessions of Nat Turner, which won a Pulitzer Prize in 1968 but was critiqued mightily in the same year by “Ten Black Writers,” and subsequently by white scholars upset by the liberties Styron took with Nat Turner’s known history, particularly scenes in which Turner fantasizes about raping a white woman and in which he has a homosexual encounter with a slave boy, both of which they charged originated in and played on stereotypes. Some of the ten black scholars collected in Styron’s Nat Turner were equally incensed by Styron’s cultural appropriation. Subsequently, African American scholars, such as historian Julian Bond, who introduced Styron at the University of Virginia, and most recently literary critic Henry Louis Gates Jr., have historicized the response to cultural appropriation as rooted in the aftermath of the Civil Rights Movement and have emphasized that the key question should not be who can write about whom, but how the writer tells the story.6 After the attacks on Styron’s novel, white writers were reluctant to write from a black point of view. Not until twenty years later did Ellen Douglas find a way to do so with her postmodern novel, Can’t Quit You, Baby (1988), which academics have lauded.

As with Styron’s novel, some general readers have accused Stockett of cultural appropriation, of “getting rich off the backs of a story that is NOT hers to tell.” Anticipating this criticism, Stockett attempted to neutralize the charge in The Help by having Skeeter bring up this concern to Aibileen. But the issue became a real-life problem for Stockett when her brother’s maid Ablene Cooper brought a lawsuit, charging that Stockett had stolen her story and her name. Not surprisingly, Stockett insisted that her characters are fictional, each an amalgam of several people. For example, she said that the feisty outspokenness of actress Octavia Spencer, whom she met while writing the novel, was an inspiration for her character Minny. What is surprising is that Stockett naively used a name and a nickname for her character Aibileen/Aibee, which is identical in pronunciation to Ablene Cooper’s. Before the lawsuit was filed, Stockett explained, both in interviews and in the acknowledgments and afterword to the novel, that the story was inspired by her memories of Demetrie, her childhood caretaker, and augmented by information gleaned from such sources as Susan Tucker’s Telling Memories Among Southern Women: Domestic Workers and Their Employers in the Segregated South (1988). In dismissing Ablene Cooper’s lawsuit because “a one-year statute of limitations had elapsed between the time Stockett gave Cooper a copy of the book and when the lawsuit was filed against her,” the judge may have done little to lay the matter of appropriation to rest for some general readers.7

Much of the scholarly criticism of the film has been heaped on Hollywood for always choosing to tell the help’s story from Miss Daisy’s perspective, making a white character the heroic savior of helpless black people. In her introduction to a special issue on the film, Nzegwu argues that films “such as To Kill a Mockingbird (1962), Mississippi Burning (1988), Ghosts of Mississippi (1996), and now The Help (2011) derive from the center of white solipsism, to redeem the tarnished reputation of racist whites”: “This strategy of presenting only the stories of good, sympathetic, upright white defenders of hapless Blacks enables Hollywood to mask the extraordinary courage, and the powerful human interest stories of black agency challenging a frightful, murderous system. By mischaracterizing racism as racial prejudice and representing it as based on ignorance, films like The Help transform the South into an idyllic world, minimally marked by segregation and racism.”8

Agreeing with Nzegwu, many scholars, no matter their race or ethnicity, have focused on Stockett’s stereotypical portrayal of both black and white characters and her sanitized depiction of the Civil Rights era. But African American scholars have been far quicker to comment in the public forum than white scholars. They have written op-eds in such prominent newspapers as the New York Times and the Washington Post, as well as commented on radio, television, and blogs. On August 12, 2011, a few days after the film was released, the Association of Black Women Historians posted a response to The Help on Amazon.com [see the sidebar on page 32], which praised the performances of the African American actresses in the film, but drew attention to shortcomings in both the novel and the fil...