eBook - ePub

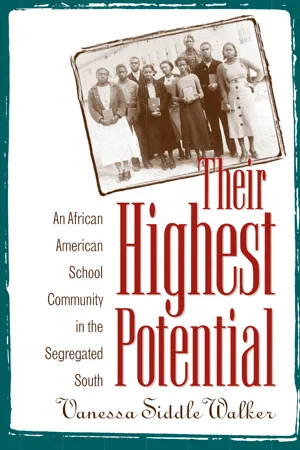

Their Highest Potential

An African American School Community in the Segregated South

- 276 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Their Highest Potential

An African American School Community in the Segregated South

About this book

African American schools in the segregated South faced enormous obstacles in educating their students. But some of these schools succeeded in providing nurturing educational environments in spite of the injustices of segregation. Vanessa Siddle Walker tells the story of one such school in rural North Carolina, the Caswell County Training School, which operated from 1934 to 1969. She focuses especially on the importance of dedicated teachers and the principal, who believed their jobs extended well beyond the classroom, and on the community's parents, who worked hard to support the school. According to Walker, the relationship between school and community was mutually dependent. Parents sacrificed financially to meet the school's needs, and teachers and administrators put in extra time for professional development, specialized student assistance, and home visits. The result was a school that placed the needs of African American students at the center of its mission, which was in turn shared by the community. Walker concludes that the experience of CCTS captures a segment of the history of African Americans in segregated schools that has been overlooked and that provides important context for the ongoing debate about how best to educate African American children. African American History/Education/North Carolina

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Their Highest Potential by Vanessa Siddle Walker in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & History of Education. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter One: A Couple of Three Years Ago

They called him “Chicken” Stephens instead of his real name, John. He’d moved to Yanceyville from neighboring Rockingham County in 1866. The story of his problems was not long in following. The newcomer, it was said, was responsible for killing two of his neighbors’ chickens when they strayed onto his property in Rockingham, and he was reported to have attacked the neighbor and shot two bystanders the next morning out of anger about having been jailed overnight. They said he sold his mother’s home and tried to abandon her when he moved. When she later followed him to Yanceyville and died—reportedly as the result of a fall from bed, in which she cut her throat on the chamber pot—a widely circulated rumor held that Stephens had slit her throat.1

Such were the stories surrounding Stephens’s personal life. But these so-called dastardly deeds hardly seem the basis for the guilt sentence imposed upon him by the Ku Klux Klan. More likely, the difficulty that aroused the Klan’s wrath toward Stephens stemmed from another source. Stephens was a white Republican. In his new home in Yanceyville, he was said to have “associated freely with blacks and was suspected of inspiring them to burn a number of barns, destroy crops, steal livestock, and otherwise contribute to the general unrest that disturbed the county.” Although African Americans remember him as having been a friend to the newly freed slaves and “don’t believe he encouraged [anyone] to burn any crops,” the historical record emphasizes the disturbances he was reported to have created and reports that he was a “willing tool in the hands of [carpetbaggers]”: he was “useful to them in herding blacks to the polls.” To further fuel the ire of white Democrats, he was elected in 1868 to represent the county in the state senate.2

Perhaps Stephens received word that he had been placed on trial by the Klan and had been found guilty. According to a Caswell County history, he “took out a large insurance policy on himself, fortified his house ..., and armed himself with three pistols.” A review of courthouse records also indicates that he wrote a will just two months before the attack. In the opening paragraph of that will, he bequeathed all his property to his wife, Martha, “two thirds of the same to be held in trust by the said Martha E Stephens for the use of my children, to be equally divided among said children as they shale respectfully attain majority.” His holdings included his home and four acres of land; the real and personal property was later valued in probate court at $ 11,000.3

Chicken Stephens’s will went into effect on 21 May 1870, when the Klan killed him in a small room that had recently been vacated by the Freedman’s Bureau on the first floor of the majestic courthouse on the town square. The crime was committed during the daylight hours while a local Democratic convention was being held on the second floor; the body was not found on the bloodstained wood stack until the next morning.4 Soon after burying him in a local cemetery, Martha Stephens and children left the town, and the real property willed to them by the deceased husband and father was left vacant for over thirty years. “White folks wouldn’t live in it,” reports Mary Jackson, a keeper of courthouse records and informal historian of African American history in Caswell County, and because of the social mores of the time, “colored folk couldn’t live in it.”

So begins the history that subsequently leads to CCTS. Church schools for Negroes that were organized just after the Civil War and met for an hour or two a day are reported to have been the earliest Negro schools in the county. The first documented forerunner to CCTS, however, was the Yanceyville Colored School, chartered in the North Carolina Session Laws of 1897.5 Remembered in contemporary accounts as the “Stephens House,” this school represents the first evidence of the role parents and community leaders played in the education of Negro children.6

Early Beginnings and Parental Support

From her chair in a nursing home, Katie Bowe recalls that she began school in the Stephens House in 1907. She remembers that the school was a “regular” house, with two rooms upstairs, two downstairs, and a stairway in the hall. The school, she explains, was named for a white family by the name of Stephens. Since she was only seven years old when she began attending the school, she is unsure who the Stephenses were or how their property came to be in the possession of Negro teachers and children.

Most other oral accounts of the history also convey uncertainty about how the house came to be used as a Negro elementary school for the Yanceyville population. Some know that it had something to do with Chicken Stephens; some believe the house was given by a white citizen; some think the board of education purchased it and donated it to Negroes because no one would live in it. Sharecropper George Lafayette Wade, deceased since 1926, held the latter opinion. According to his granddaughter Mary Jackson, he is reported to have said, “Well, they didn’t know what to do with the house, so they give it to the niggers for the school.” Though Wade was a contemporary of the events and a Negro member of the community, he too believed the house to have been a gift of the school board.

Courthouse records differ from the oral accounts. A deed dated 8 May 1906 shows that Chicken Stephens’s daughters and a son-in-law, then residents of Tennessee, sold the “four acres more or less and known as ‘the John W. Stephens House and lot’” to several Negro citizens for the sum of $400. These citizens are listed as W. H. Burwell, T. S. Lea, James Johnston, N. T. Hill, J. L. Lea, Hannah Johnston, and Louisa Graves.7 All of them were well-known and respected in the community. Burwell, who “wasn’t a poor man” and who wanted a better and bigger school for the Negro children, is reported to have been the existing school’s principal. He is also among the people listed on the 1897 state charter for the Yanceyville School, where the listed patrons were given the authority to “make whatever rules and regulations were necessary.”8 At minimum, the presence of his name on this subsequent purchase indicates at least eight years of leadership and active involvement, as well as financial commitment, to Negro education.

T. S. Lea was “one of the richest black men in Yanceyville” and was also one of the “colored committeemen” for the Negro school. (Negro and white local committeemen were appointed by the school board for each school district to assist the board in determining school needs across the county.) Nathaniel Hill, owner of a local livery stable, had a “nice home” and was considered “well-to-do”; Hannah Johnston owned a house on Main Street. In short, the purchasers were prominent Negro citizens who pooled their resources to buy the vacant house and convert it into use for the Negro school children.9 The rooms upstairs were used for community meetings, the rooms downstairs as classrooms.

By 1919 the old house had become known as the Yanceyville School and was already so overcrowded that “teachers had to resort to boxes for seats for the children.” Katie Bowe’s teacher in 1907, Elsie Greene Simmons, was still at the school in 1919 and experienced those crowded conditions. Residing in a rest home about six miles from that of her former student as late as 1992, Simmons, then Elsie Green Palmer, was still able to verify that she had come from neighboring Danville, Virginia, to teach in the Yanceyville School. According to the written history of the Parent-Teacher Association (PTA), she and fellow teacher Novella Evans raised money through ice cream sales and programs to help provide supplies for the school in 1919.10 At the end of the school year, talk in the community had already turned to getting a new school to relieve the congested conditions, so the two teachers left twelve dollars of their collected funds with Negro school commissioner T. S. Lea to be applied toward the purchase of the new school.11 These funds are the first recorded contribution for the building that would later become the Caswell County Training School.

No reference is ever made as to whether the Negro community at that point expected to make another private purchase or if its leaders were already aware of the existence of Rosenwald funds to help build such schools. The latter is probable: four years earlier, philanthropist Julius Rosenwald had contributed $800 toward the construction of the first school for Negroes in North Carolina. Built in 1915, the school employed two teachers and cost $1,622; Negroes raised $486 toward its completion. Three years earlier, the Executive Council of Tuskegee, through whom Rosenwald contributions were initially channeled, had made $6,000 available to N. C. Newbold, director of the Department of Rural Elementary Schools, to be used for constructing twenty Negro schools in the state of North Carolina. By 1919, when the Yanceyville teachers left their first funds to be applied to a new building, the private fund set up by Rosenwald to provide matching monies to Negro patrons for the construction of schools had already been formally in existence since 1917.12

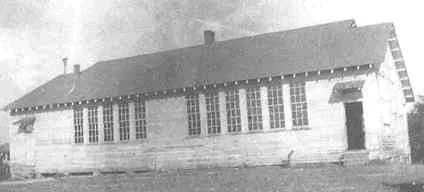

In 1925, black parents contributed $800 in cash and labor to build a four-room Rosenwald school for Yanceyville’s elementary school children. (Photo courtesy of Nancy Lea)

In 1924, building plans accelerated. The PTA was first formally organized that year with the assistance of Caswell County’s Negro Jeanes supervisor, Valina Whitfield. It had as its initial objective the building of the school.13 Toward accomplishing that goal, PTA leaders Emma Williamson and Esther Bigelow led the group’s members to raise $800 toward the building.14 Emma Williamson’s daughter, Janie Richmond, recalls that her mother used church contacts to call people together and talk with them about the “dire need” for the school. She reports that people in the community were very interested in contributing, in part because the school also provided the community with a form of recreation. As a means of gathering money for the building, the PTA sponsored socials and taffy pulls, events in which Negro patrons at every level of income could pay a small amount of money and participate. By 1925, they had raised sufficient funds for their portion of the contribution, and the school-a four-room Rosenwald with a kitchen-was completed.

When the children moved next door from the Stephens House to the new Rosenwald school, they moved into the newest, most spacious educational facility that had ever been available for Negro children in the county. Although the Yanceyville School, as it came to be known, was not the county’s first Rosenwald school, at a cost of $4,465, it was the largest and most expensive Rosenwald school.15 The Rosenwald school that had been built for Negro children in the Blackwell community of the county in 1923, for example, was a two-room plan that cost $2,700 to build. Other Rosenwald schools for the Negro children built after the Yanceyville School was completed also used the two-room plan, and they varied in price from $1,800 to $2,100.

These prices, of course, made the the county’s Rosenwald schools exceptionally well constructed Negro schools compared to the other thirty-plus one-room Negro schools, where parents relied primarily on school board resources. Between 1925 and 1929, for example, the school board supplied allotments of 500-$700 for new construction of one-room Negro schools, a cost of $1,100 under the least expensive Rosenwald school. Schools that were not new could not even be compared. Existing Negro schools at the time were being sold to the highest bidder for as low as $30 to $40 when they were discontinued as school buildings.16 With its four rooms and kitchen, the Yanceyville School was a model for Negro facilities in the county.

But though the Yanceyville School exceeded by several thousand dollars the expenditures for the county’s other Rosenwald schools and far outdistanced the facilities of the Negro one-room schools, the building in no way equaled the facilities of area white schools. The neighboring white Yanceyville High School was allocated $9,000 in 1923, along with an extra $225 for a piano. The same year, the Leasburg School, which had already been allotted eight rooms at $22,118, received an additional $500 for auditorium chairs, while Cobb received $7,300 to complete a teacherage (housing for out-of-town teachers) and two extra classrooms. Even accounting for the size difference between the Leasburg School and the Yanceyville School, the cost differential in construction indicates that only one-third the amount per classroom was spent on the Negro school as on the white school. Moreover, the white Milton School, constructed just two years after the Yanceyville School was completed, was a comparable building—a four-room school with an auditorium—yet the county budgeted $15,000 for its construction. Even the cost of a discontinued white school was valued at $200 in 1926, compared to $30-40 for Negro schools.17 Thus, the Yanceyville School, while a model of Negro buildings in the county at the time, was not in physical terms a model of educational equality.

Context of Parental Advocacy

Negro parents were pleased to have the new Rosenwald building, but having a building alone was not enough. They still wanted high school education to be available to all the Negroes in the county. In the present circumstances, Negro parents who wanted a child to have an education beyond elementary school were forced to send the child to neighboring cities in other counties, while white children could choose from among three high schools as early as 1924, and more had subsequently been added.18 Many Negro parents were not able to make the sacrifices such a move entailed.

The parents who rose to assume the initiative in plans to start a high school in Yanceyville, and who continued to assume leadership roles in the school over the years, may be called “advocates.” In general, these advocates were parents and community leaders who interposed themselves between the needs of the Negro community and the power of the white school board and made requests on behalf of the school. Sometimes they made these requests directly to the board; sometimes they appealed to school supervisors at the state capitol. In addition to helping implement PTA projects deemed to be for the good of the children, they also often made financial contributions using their own resources.

Like the citizens who had purchased the Stephens House twenty or more years earlier, advocates included both men and women and were generally well-to-do by Negro standards. A common link among them seems to be that most owned their own farms or operated some type of small business. Although the advocates themselves and their descendants do not attribute importance to their occupations, the occupations cannot be discounted, because their self-sufficiency made them less vulnerable to the economic reprisal that could have occurred if they had been more dependent on whites for their income. This group frequently included ministers as well, perhaps in part because they too depended on other Negroes for financial stability.

Yet to understand the advocates’ actions requires an understanding of the context in which they were forced to operate. In addition to the white school board’s lack of commitment to Negro education, as evidenced by the inequality of facilities provided, the local three-member board also had several unwritten ways of dealing with Negro parents. When delegations appeared before the board to make requests, for example, several responses were consistently used. Frequently, these included a delay response that involved deferring the matter until some unnamed time, until a specific time, or until some investigation could be made. Although whites too were sometimes victims of such delay responses, when the board either did not have the money for a requested project or was unwilling to make a commitment to it, the lack of specificity sometimes characteristic of the delays used with Negro requests is captured in the following examples: “The Board [is] not able to help at this time ... but will take up the matter as soon as possible”; “motioned to give matter consideration for another year. Letter filed”; “motion carried to ... let the patrons know later the final decision of the Board.”19

Other board responses to Negro requests included agreeing to provide the request if the Negro community made some type of personal sacrifice; accepting a particular Negro contribution (such as lending a stove to the school) but making no monetary commitment of its own; agreeing to grant the request “if money [was] available”; and asking the Negro community to consider other sources of money. Of the seventeen...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Their Highest Potential

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Illustrations

- Preface

- Introduction Remembering the Good

- Chapter One: A Couple of Three Years Ago

- Chapter Two: The Plot Thickens

- Chapter Three: Working Together

- Chapter Four: Meeting Needs

- Chapter Five: We Are Family

- Chapter Six: Their Highest Potential

- Chapter Seven: Standing on Moving Ground

- Afterword: No Poverty of Spirit

- Appendix: Notes on Methodology

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index