- 344 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

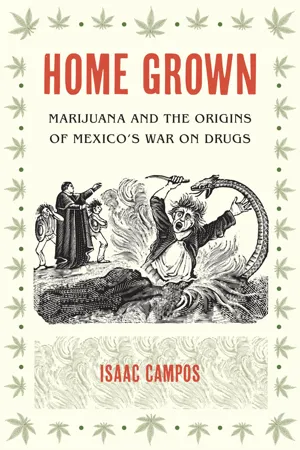

About this book

Historian Isaac Campos combines wide-ranging archival research with the latest scholarship on the social and cultural dimensions of drug-related behavior in this telling of marijuana’s remarkable history in Mexico. Introduced in the sixteenth century by the Spanish, cannabis came to Mexico as an industrial fiber and symbol of European empire. But, Campos demonstrates, as it gradually spread to indigenous pharmacopoeias, then prisons and soldiers' barracks, it took on both a Mexican name — marijuana — and identity as a quintessentially “Mexican” drug. A century ago, Mexicans believed that marijuana could instantly trigger madness and violence in its users, and the drug was outlawed nationwide in 1920.

Home Grown thus traces the deep roots of the antidrug ideology and prohibitionist policies that anchor the drug-war violence that engulfs Mexico today. Campos also counters the standard narrative of modern drug wars, which casts global drug prohibition as a sort of informal American cultural colonization. Instead, he argues, Mexican ideas were the foundation for notions of “reefer madness” in the United States. This book is an indispensable guide for anyone who hopes to understand the deep and complex origins of marijuana’s controversial place in North American history.

Home Grown thus traces the deep roots of the antidrug ideology and prohibitionist policies that anchor the drug-war violence that engulfs Mexico today. Campos also counters the standard narrative of modern drug wars, which casts global drug prohibition as a sort of informal American cultural colonization. Instead, he argues, Mexican ideas were the foundation for notions of “reefer madness” in the United States. This book is an indispensable guide for anyone who hopes to understand the deep and complex origins of marijuana’s controversial place in North American history.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Home Grown by Isaac Campos in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Mexican History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

Cannabis and the Psychoactive Riddle

As I detail in chapter 4, marijuana caused violence, madness, and crime in nineteenth- and early-twentieth-century Mexico. This, anyway, is what the available historical sources overwhelmingly indicate. These ideas were widespread and appear to have cut across boundaries of class and ethnicity. There was almost no counterdiscourse, there were virtually no defenders of the weed, and there was remarkable continuity in the way this substance was portrayed, whether in newspapers or in scientific periodicals. Marijuana’s effects were sometimes simply described as “madness,” and, while hardly a clinical diagnosis, the dimensions of this particular brand of insanity were relatively consistent—irrational and sudden outbursts of violence, hallucinations, delusions, superhuman strength, and sometimes amnesia.

Given the sheer volume of reports on these effects and their overwhelming consistency, it is tempting simply to accept them at face value. In fact, with another subject or in another context, the overwhelming consistency of the evidence would already be proof enough of this drug’s effects in that time and place. But in this case, we must proceed with caution, for there is significant dissonance here with more recent cannabis experience in North America. If marijuana was producing violent delirium a century ago, why isn’t it producing those effects today? Furthermore, because we know that marijuana was used mostly by the lower class—people often considered criminal and violent as a matter of course by Mexican authorities—there is much reason to suspect that these claims were at the very least exaggerated. Yet the volume and consistency of the evidence is extraordinary, more extraordinary even than the flagrant, sometimes ostentatious prejudice of Mexicans a century ago.

But could cannabis really have caused these effects? Here we have a relatively simple question that has a decidedly complicated answer. One might expect otherwise. In fact, when I began this research, I expected the scientifically measurable effects of cannabis to be a straightforward control for understanding the past. My assumption went something like this: If we know the effects that a drug has in the present, then we will know what effects the drug had in the past, producing a perfect control for distinguishing between myth and reality in the historical archive. This, it turns out, was wrong.

Richard DeGrandpre has called this widespread misunderstanding the “cult of pharmacology” and has identified it as a key component in the genesis and longevity of misguided drug policies in the United States. The cult of pharmacology suggests that there is a direct and consistent relationship between the pharmacology of a substance and the effects that it has on all human beings. But as decades of research and observation have demonstrated, the effects of psychoactive drugs are actually dictated by a complex tangle of pharmacology, psychology, and culture—or “drug, set, and setting”—that has yet to be completely deciphered by researchers. For the sake of convenience, we might simply call that tangle the “psychoactive riddle.”

This book seeks to decipher the psychoactive riddle of cannabis in nineteenth- and early-twentieth-century Mexico. Thus we must begin, ironically, with a few basic questions that will briefly delay our voyage into Mexican history. First, was the Mexican case unique? Was cannabis ever reported to produce similar effects in other times and places? Second, what can the latest science tell us about cannabis pharmacology? Does this drug even have the potential to produce the effects that were so often attributed to it in Mexico a century ago? The answers may surprise you.

During the early modern era, reports began to emerge in Western sources of the apparently pernicious effects of cannabis. According to historian James Mills, one of the more important accounts of this kind appeared in a little guide published, beginning in 1779, as the Portable Instructions for Purchasing the Drugs and Spices of Asia and the East Indies. Here, cannabis (bhang) was described as a “species of opiate in much repute throughout the East for drowning care.... The effects of this drug are to confound the understanding, set the imagination loose and induce a kind of folly or forgetfulness.”5 But the Portable Instructions also warned of more sinister effects. These had been reported a few years earlier by the British traveler and businessman John Henry Grose, whose work for the East India Company had apparently facilitated his observations on the subject:

Bang is also greatly used at Surat, as well as all over the East, an intoxicating herb, of which it may be needless to say more after so many writers, who have fully described it: and it is hard to say what pleasure can be found in the use of it, being very disagreeable to the taste, and violent in its operation, which produces a temporary madness, that in some, when designedly taken for that purpose, ends in running what they call a-muck, furiously killing every one they meet, without distinction, until themselves are knocked on the head, like mad dogs. But by all accounts this practice is much rarer in India than it formerly was.6

According to Mills, the Portable Instructions was especially important to the diffusion of ideas about cannabis in the West because the work was repeatedly reprinted as an appendix to other similar guides that then circulated the globe in the baggage of European business travelers. For example, the Portable Instructions was appended to The India Officers and Traders Guide in Purchasing the Drugs and Spices of Asia and the East Indies, which became “the definitive guide to sailing from Britain, France, or America to India” and remained in circulation until at least the First World War. Grose’s book, from which the above quotation was originally drawn, was also quite popular in its own right, published first in 1757, translated into French in 1758, and seeing three editions by 1772.7

In the nineteenth century, this developing lore achieved additional legitimacy thanks to the backing of some of the era’s greatest intellectuals. In part, this was due to a confluence of historical factors, even an accident of history, that made cannabis into a substance of profound fascination for the “Western mind.” This was a period, of course, that saw the interconnected ascendancy of science and colonialism, which manifested itself perhaps most obviously in the burgeoning field of Orientalism. It was also an era that saw a boom in the botanical sciences and pharmacology, producing the discoveries of countless wonder drugs. Cannabis was ideally suited to garner attention in this atmosphere. It was an Old World drug that had gained fame in The Thousand and One Nights, surely the most famous of “Oriental” sources. It was also a plant that appeared almost naturally inclined to reproduce the basic dichotomies at the heart of the Oriental-Occidental divide, for the species had two forms: in temperate regions, it appeared to produce mostly fiber; in the tropics, mostly drugs. As James F. W. Johnston explained in 1855:

Our common European hemp (Cannabis sativa) ... so extensively cultivated for its fibre, is the same plant with the Indian hemp (Cannabis indica), which from the remotest times has been celebrated among Eastern nations for its narcotic virtues....

In the sap of this plant ... there exists a peculiar resinous substance in which the esteemed narcotic virtue resides. In northern climates, the proportion of this resin in the several parts of the plant is so small as to have escaped general observation....

But in the warmer regions of the East, the resinous substance is so abundant as to exude naturally, and in sensible quantity, from the flowers, from the leaves, and from the young twigs of the hemp-plant.... It grows well, and produces abundance of excellent fibre in the north, but no sensible proportion of narcotic resin. It grows still better, and more magnificently, in tropical regions; but there its fibre is worthless and unheeded, while for the resin it spontaneously yields it is prized and cultivated.8

In short, in the “East,” cannabis appeared to naturally produce drug content fit for inducing revelry and escapism, while in colder climates, it yielded plentiful fiber ideally suited to industry and progress.

It should hardly be surprising, then, that probably the most influential source on the nature of cannabis during this era was not produced by a botanist but rather by Silvestre de Sacy, the most renowned Orientalist of the nineteenth century. In his “Memoir on the Dynasty of the Assassins, and on the Etymology of Their Name,” Sacy argued that the origins of the word “assassin” were found in the word “hashish.”9 This argument was extraordinarily influential and did as much as anything to legitimize the view among Westerners that cannabis had the potential to produce at least fantastic visions if not violence in its users. It thus deserves a few moments of our attention here.

Sacy’s theory was based in the history of a medieval Shiite Islamic sect called the Isma’ilis, popularly known as the “Order of Assassins.” The Isma’ilis were much maligned during the Middle Ages by both rival Muslims and Christians. Among Muslims, they were portrayed as a secret conspiracy featuring complex initiation rites and bent on destroying Islam. Crusading Christians later elaborated on that unsavory reputation. The Isma’ilis themselves fueled the process with the adoption in the twelfth century of public assassination as a central tactic in their struggle against the Sunni Saljuq Turks. Though they did not pioneer this tactic, they did employ it in a most “spectacular and intimidating fashion,” with young men (called fidawi) assassinating often important, well-guarded officials, most commonly in public places like mosques where the acts would therefore also serve as tools of intimidation.10 It was all the more intimidating, of course, because the fidawi knew they would surely be killed in the process. They were, in short, probably the most famous “suicide bombers” of all time.

Predictably, the Isma’ilis became the targets of many choice insults, the most common of which were malahida (heretics) and batiniyya (meaning, more or less, “irreligiosity”) but also, as Sacy later emphasized, al-Hashishiyya. Indeed, the first written use of the word hashishiyya appears in a polemic against the Isma’ilis in 1123.11 This was a moment when hashish use was spreading around the Muslim world and gaining a reputation as low-class and antithetical to Islam.12 There exists no evidence, however, that the Ismai’ilis or, in particular, the fidawi assassins had anything to do with hashish. The original sources never explain why the word is utilized, and as historian Farhad Daftary has argued, it seems rather unlikely that warriors sent on such difficult and sensitive missions would have taken a potentially disorienting drug in order to carry them out.13 Furthermore, hashisha was a term used as a general insult in the Arab world due to its association with heretics and the rabble of society. It thus seems most likely that the word was simply being employed in this pejorative sense rather than as an actual accusation of hashish use.

Sacy nevertheless speculated that the insult may have had some basis in the actual employment of hashish. Marco Polo’s Travels provided the evidence. There, Polo described an “Old Man of the Mountain” who had created an impregnable castle with sumptuous gardens, rivers of milk and honey, and many young and beautiful virgins whose “duty was to furnish the young men who were put there with all delights and pleasures.” The old man would keep scores of these youngsters at his court, all of whom were to become warriors, and he would describe to them the pleasures of paradise and explain that he had the key to it. Whenever he needed an enemy assassinated, he would have a group of these warriors secretly drugged with a potion so that they would fall into a deep sleep. He would then have them carried into the gardens of the castle so that when they awoke, they could experience the pleasures of paradise for a few days. The boys would later be drugged again and removed from the gardens, only to awake to the overwhelming disappointment of the real world. The old man would then promise their return in exchange for unwavering obedience. It was said that these young warriors thus became so fanatically loyal that they were willing to carry out virtually any task for their master, even if it meant they would perish in the process. Christian Crusaders had found in this legend an attractive explanation for the seemingly irrational behavior of the suicidal fidawi. Thus, stories began circulating in the late twelfth century among Christian sources, describing the Old Man of the Mountain, his magical potion, and his promises of paradise. The story went through several incarnations before Marco Polo’s version became the standard European account.14

Though hashish is not actually mentioned in the tale, Sacy took the presence of the secret potion in the anecdote as evidence enough of the drug’s critical role in producing visions of paradise. In fact, Sacy questioned the actual existence of the gardens themselves, arguing instead that they were probably just a product of young imaginations fueled by hashish. Here he echoed the basic reputation of cannabis as provided in the Thousand and One Nights. “What we know for certain is that even today, people who take opium or hashish can, even if covered in poverty’s rags and staying in a miserable tavern, derive happiness and pleasures that are short nothing but reality.”15

Sacy’s great influence helped turn the Assassins legend into a crucial component of European writings on cannabis. But in the process, the moral of the story as it related to cannabis drugs was increasingly distorted, for other authors were considerably less shy about directly linking the frightening, suicidal assassinations of the fidawi to the effects of hashish. As the American poet and travel writer Bayard Taylor put it in 1854, “During the Crusades, [hashish] was frequently used by the Saracen warriors to stimulate them to the work of slaughter, and from the Arabic term of ‘Hashasheen,’ or Eaters of Hasheesh, the word ‘assassin’ has been naturally derived.”16 At midcentury, Ernest von Bibra and James F. W. Johnston both produced monographs on the world’s intoxicants that summarized the existing knowledge of cannabis’s effects. Both of them referenced Sacy’s work prominently, with Johnston noting that “it is from such effects of this substance also that we obtain a solution of the extravagances and barbarous cruelties which we read of as practised occasionally by Eastern despots.”17 Sacy’s study would in fact be cited as authoritative for more than a century after its publication. During the 1930s, Harry Anslinger of the U.S. Federal Bureau of Narcotics would famously employ the Assassins legend, both in his article “Marihuana: Assassin of Youth” and later during congressional testimony to help secure marijuana prohibition in the United States: “In the year 1090, there was founded in Persia the religious and military order of the Assassins whose history is one of cruelty, barbarity, and murder, and for good reason. The members were confirmed users of hashish, or marihuana, and it is from the Arabic ‘hashshashin’ [sic] that we have the English word ‘assassin.’ Even the term ‘running amok’ relates to the drug, for the expression has been used to describe natives of the Malay Peninsula who, under the influence of hashish, engage in violent and bloody deeds.”18

Meanwhile, many other nineteenth-century sources reinforced the view that cannabis was a quintessentially Oriental substance that produced either visions or violence or both. Von Bibra, for example, claimed that “for Orientals, the common effect of hashish is of an agreeable, exciting ch...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Home Grown

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Figures, Charts, and Tables

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- Chapter 1 Cannabis and the Psychoactive Riddle

- Chapter 2 Cannabis and the Colonial Milieu

- Chapter 3 The Discovery of Marijuana in Mexico

- Chapter 4 The Place of Marijuana in Mexico, 1846–1920

- Chapter 5 Explaining the Missing Counterdiscourse I

- Chapter 6 Explaining the Missing Counterdiscourse II

- Chapter 7 Did Marijuana Really Cause “Madness” and Violence in Mexico?

- Chapter 8 National Legislation and the Birth of Mexico’s War on Drugs

- Chapter 9 Postscript

- Conclusion

- Appendix

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index